Abstract

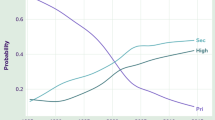

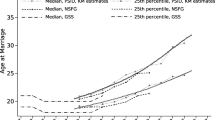

This study examines proximate sources of change in first-marriage trajectories in the United States between 1960 and 2010. This was a period of tremendous social change: divorce became more common, people started marrying later or not marrying at all, innovations in medicine and changes in social and behavioral factors led to reduced mortality, inequality grew stronger and was reflected by more intense assortative mating, and the country underwent a massive educational expansion. Each of these factors influenced the formation and dissolution of first marriages over this period. This article extends the multiple-decrement life table to incorporate heterogeneity and assortative mating, which allows the quantification of how changes in the incidence of marriage, divorce, and mortality, along with changes in educational attainment and assortative mating, have shaped trends in first-marriage trajectories. The model is used to prove that stronger educational assortative mating leads to longer average durations of first marriage. Using data from multiple sources and this model, this study shows that although the incidence of divorce was the primary determinant of changes in first-marriage trajectories between 1960 and 1980, it has played a relatively smaller role in driving change in marital trajectories between 1980 and 2010. Instead, factors such as later age at first marriage, educational expansion, declining mortality, narrowing sex differences in mortality, and more intense educational assortative mating have been the major drivers of changes in first-marriage trajectories since 1980.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Probability of widowerhood is fully determined as 1 minus the probability that a marriage will end in widowhood or divorce. For parsimony, figures on widowerhood are not included in the main text but are available on request.

Not all these 15-year-olds will eventually get married because in general, the hτ(x|cf, cm) function does not integrate to 1. To compute quantities referring only to the ever-married population (e.g., probability that a marriage will end in divorce), I normalize this function to sum to 1 and thus provide estimates that are conditional on marriage, which are concerned only with the ever-married population.

References

Axinn, W. G., & Thornton, A. (1993). Mothers, children, and cohabitation: The intergenerational effects of attitudes and behavior. American Sociological Review, 58, 233–246.

Bennett, N. G., Blanc, A. K., & Bloom, D. E. (1988). Commitment and the modern union: Assessing the link between premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital stability. American Sociological Review, 53, 127–138.

Brown, S. L., & Lin, I.-F. (2012). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990–2010. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 731–741.

Bumpass, L., & Lu, H. H. (2000). Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies, 54, 29–41.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2012). Vital signs: Unintentional injury deaths among persons aged 0–19 years: United States, 2000–2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61, 270–276.

Das Gupta, P. (1993). Standardization and decomposition of rates: A user’s manual (Current Population Reports P23-186). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Easterlin, R. A. (1987). Easterlin hypothesis. In J. Eatwell, M. Milgate, & P. Newman (Eds.), The new Palgrave dictionary of economics (Vol. 2, pp. 1–4). New York, NY: Stockton Press.

Edin, K., & Kefalas, M. (2005). Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Elliott, D. B., Simmons, T., & Lewis, J. M. (2010). Evaluation of the marital event items on the ACS (Working paper). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Elo, I. T., & Preston, S. H. (1996). Educational differentials in mortality: United States, 1979–1985. Social Science & Medicine, 42, 47–57.

Elwert, F., & Christakis, N. A. (2008a). The effect of widowhood on mortality by the causes of death of both spouses. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 2092–2098.

Elwert, F., & Christakis, N. A. (2008b). Wives and ex-wives: A new test for homogamy bias in the widowhood effect. Demography, 45, 851–873.

Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2002). The power of the pill: Oral contraceptives and women’s career and marriage decisions. Journal of Political Economy, 110, 730–770.

Goldman, N., & Lord, G. (1983). Sex differences in life cycle measures of widowhood. Demography, 20, 177–195.

Hendi, A. S. (2015a). The demography of modern social transformations (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Hendi, A. S. (2015b). Trends in U.S. life expectancy gradients: The role of changing educational composition. International Journal of Epidemiology, 44, 946–955.

Hendi, A. S. (2017). Trends in education-specific life expectancy, data quality, and shifting education distributions: A note on recent research. Demography, 53, 1203–1213.

Hernes, G. (1972). The process of entry into first marriage. American Sociological Review, 27, 173–182.

Ho, J. Y. (2017). The contribution of drug overdose to educational gradients in life expectancy in the United States, 1992–2011. Demography, 54, 1175–1202.

Ho, J. Y., & Fenelon, A. (2015). The contribution of smoking to educational gradients in U.S. life expectancy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 56, 307–322.

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11, 213–218.

Jose, A., O’Leary, K. D., & Moyer, A. (2010). Does premarital cohabitation predict subsequent marital stability and marital quality? A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 105–116.

Kennedy, S., & Bumpass, L. L. (2008). Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research, 19, 1663–1692. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.4

Kennedy, S., & Ruggles, S. (2014). Breaking up is hard to count: The rise of divorce in the United States, 1980–2010. Demography, 51, 587–598.

Kitagawa, E. M., & Hauser, P. M. (1973). Differential mortality in the United States: A study in socioeconomic epidemiology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kulu, H., & Boyle, P. (2010). Premarital cohabitation and divorce: Support for the “trial marriage” theory? Demographic Research, 23, 879–904. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2010.23.31

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 36, 211–251.

Lucas, R. E., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2003). Reexamining adaptation and the set point model of happiness: Reactions to changes in marital status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 527–539.

Ma, J., Ward, E. M., Siegel, R., & Jemal, A. (2015). Temporal trends in mortality in the United States, 1969–2013. JAMA, 314, 1731–1739.

Manning, W. D., & Cohen, J. A. (2012). Premarital cohabitation and marital dissolution: An examination of recent marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 377–387.

Manning, W. D., Longmore, M. A., & Giordano, P. C. (2007). The changing institution of marriage: Adolescents’ expectations to cohabit and to marry. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 559–575.

Mare, R. D. (1991). Five decades of educational assortative mating. American Sociological Review, 56, 15–32.

Martin, S. P. (2006). Trends in marital dissolution by women’s education in the United States. Demographic Research, 15, 537–560. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2006.15.20

Martin, S. P., Astone, N. M., & Peters, H. E. (2014). Fewer marriages, more divergence: Marriage projections for Millennials to age 40 (Report). Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Minnesota Population Center. (2012). Integrated Health Interview Series: Version 5.0. (Minnesota Population Center and State Health Access Data Assistance Center, Ed.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. Accessed at http://www.ihis.us

Myrskyla, M., & Goldstein, J. R. (2013). Probabilistic forecasting using stochastic diffusion models, with applications to cohort processes of marriage and fertility. Demography, 50, 237–260.

O’Connell, M., Gooding, G., & Ericson, L. (2007). Evaluation report covering marital history, final report (2006 American Community Survey Content Test Report P.9). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1988). A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 563–591.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (2000). The continuing importance of men’s economic position in marriage formation. In L. J. Waite, C. Bachrach, M. Hindin, E. Thomson, & A. Thornton (Eds.), The ties that bind: Perspectives on marriage and cohabitation (pp. 283–301). New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Preston, S. H. (1987). Estimation of certain measures in family demography based upon generalized stable population relations. In J. Bongaarts, T. K. Burch, & K. W. Wachter (Eds.), Family demography: Methods and their application (pp. 40–62). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Preston, S. H., Glei, D. A., & Wilmoth, J. R. (2010). A new method for estimating smoking-attributable mortality in high-income countries. International Journal of Epidemiology, 39, 430–438.

Preston, S. H., Heuveline, P., & Guillot, M. (2001). Demography: Measuring and modeling population processes. Malder, MA: Blackwell.

Preston, S. H., & Richards, A. T. (1975). The influence of women’s work opportunities on marriage rates. Demography, 12, 209–222.

Preston, S. H., & Wang, H. (2006). Sex mortality differences in the United States: The role of cohort smoking patterns. Demography, 43, 631–646.

Qian, Z., & Preston, S. H. (1993). Changes in American marriage, 1972 to 1987: Availability and forces of attraction by age and education. American Sociological Review, 58, 482–495.

Raley, R. K., & Bumpass, L. L. (2003). The topography of the divorce plateau: Levels and trends in union stability in the United States after 1980. Demographic Research, 8, 245–260. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2003.8.8

Reinhold, S. (2010). Reassessing the link between premarital cohabitation and marital instability. Demography, 47, 719–733.

Ruggles, S. (2016). Marriage, family systems, and economic opportunity in the United States since 1850. In S. M. McHale, V. King, J. Van Hook, & A. Booth (Eds.), Gender and couple relationships (pp. 3–41). Heidelberg. Germany: Springer International Publishing.

Ruggles, S., Genadek, K., Goeken, R., Grover, J., & Sobek, M. (2015). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 6.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V6.0

Sassler, S. (2004). The process of entering into cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 491–505.

Schoen, R. (1988). Modeling multigroup populations. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Schoen, R., & Nelson, V. E. (1974). Marriage, divorce, and mortality: A life table analysis. Demography, 11, 267–290.

Schoen, R., & Standish, N. (2001). The retrenchment of marriage: Results from marital status life tables for the United States, 1995. Population and Development Review, 27, 553–563.

Schwartz, C. R. (2013). Trends and variation in assortative mating: Causes and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 39, 451–470.

Schwartz, C. R., & Mare, R. D. (2005). Trends in educational assortative marriage from 1940 to 2003. Demography, 42, 621–646.

Seltzer, J. A. (2000). Families formed outside of marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1247–1268.

Smock, P. J. (2000). Cohabitation in the United States: An appraisal of research themes, findings, and implications. Annual Review of Anthropology, 26, 1–20.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2007). Marriage and divorce: Changes and their driving forces. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(2), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.21.2.27

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2011). Trends in marital stability. In L. R. Cohen & J. D. Wright (Eds.), Research handbook on the economics of family law (pp. 96–108). Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Van De Kaa, D. J. (1987). Europe’s second demographic transition (Population Bulletin, Vol. 42 No. 1). Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau.

Vespa, J. (2014). Historical trends in the marital intentions of one-time and serial cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 207–217.

Waite, L. J. (1995). Does marriage matter? Demography, 32, 483–507.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging [T32 AG000177] and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [T32 HD007242]. Thanks to Susan Brown, Irma Elo, Elizabeth Frankenberg, Michel Guillot, Jessica Ho, I-Fen Lin, and Sam Preston for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 345 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hendi, A.S. Proximate Sources of Change in Trajectories of First Marriage in the United States, 1960–2010. Demography 56, 835–862 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00769-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00769-3