Abstract

Demographic scholarship suggests that schooling plays an important role in transforming fertility preferences in the early stages of fertility decline. However, there is limited evidence on the relationship between schooling and fertility preferences that addresses the endogeneity of schooling. I use the implementation of Universal Primary Education (UPE) policies in Malawi, Uganda, and Ethiopia in the mid-1990s to conduct a fuzzy regression discontinuity analysis of the effect of schooling on women’s desired fertility. Findings indicate that increased schooling reduced women’s ideal family size and very high desired fertility across all three countries. Additional analyses of potential pathways through which schooling could have affected desired fertility suggest some pathways—such as increasing partner’s education—were common across contexts, whereas other pathways were country-specific. This analysis contributes to demographic understandings of the factors influencing individual-level fertility behaviors and thus aggregate-level fertility decline in sub-Saharan Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

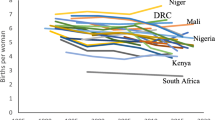

Primary schooling had a significant negative effect on pregnancy and marriage in Kenya (Duflo et al. 2012; Dupas 2011; Ferre 2009) and Nigeria (Osili and Long 2008), and a negative effect on total fertility in Malawi (Zanin et al. 2015). Secondary schooling had a negative effect on pregnancy and marriage in Malawi (Baird et al. 2010) and Kenya (Ozier 2010), and a negative effect on sexual debut in Uganda (Alsan and Cutler 2013). The literature has focused primarily on adolescent fertility outcomes rather than total fertility, likely because of the long time span needed to observe total fertility. Nonetheless, it is well documented that delays to fertility almost universally result in lower total fertility (Bongaarts 2002).

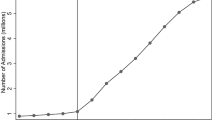

The primary school gross enrollment rate is defined as total enrollment in primary school divided by the primary age school population. This figure can exceed 100 % if children over primary school age are still in primary school.

I was unable to empirically investigate whether school affected fertility preferences of men because the association between exposure to UPE and years of schooling (the first stage) is not statistically significant for males in Malawi and Uganda. This is likely due to the greater benefit to girls than to boys from the removal of fees (World Bank 2009).

Dates in the Ethiopian data are converted to the Gregorian calendar to ensure comparability with other countries.

Major ethnolinguistic groups were those accounting for at least 10 % of the sample. I focused on ethnolinguistic background rather than ethnic group because of the large number of ethnic groups in these countries. Ethiopia and Uganda had approximately 80 and 40 ethnic groups listed in the DHS, respectively; thus, controlling for individual ethnic groups was problematic because of the small number of respondents in each group. Individual ethnic groups can be classified into broader ethnolinguistic groups sharing common linguistic and sociohistorical roots. Ethnolinguistic background captured ethnic diversity at a higher level of aggregation more suitable to this analysis.

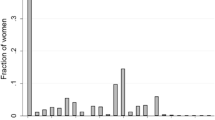

None of the women in the sample gave nonnumeric responses to ideal family size. This was consistent with Bachan and Frye’s (2013) finding that nonnumeric responses to ideal family size have decreased over time in Africa.

I reran analyses using continuous variables that measured the frequency of watching television, reading a newspaper, and listening to radio. Results were substantively unchanged.

In my final model, I did not include the control for time (birth cohort) in the first stage because this caused the birth cohort variable and exposure to UPE variable to be imprecise in the first stage in two of the three countries. This was not surprising given that the exposure to UPE variable was constructed using birth cohort (the simple correlation between exposure to UPE and birth cohort was .83 in Malawi, .82 in Uganda, and .84 in Ethiopia). Nonetheless, in the alternative model specification that controlled for time (birth cohort) in the first stage, exposure to UPE and birth cohort were jointly highly significant in the first stage in all three countries (p < .001), and the second-stage estimates were substantively unchanged (Table 5 in the appendix).

References

Ainsworth, M., Beegle, K., & Nyamette, A. (1996). The impact of women’s schooling on fertility and contraceptive use: A study of fourteen sub-Saharan African countries. The World Bank Economic Review, 10, 85–122.

Al Samarrai, S., & Zaman, H. (2007). Abolishing school fees in Malawi: The impact on education access and equity. Education Economics, 15, 359–375.

Alsan, M. M., & Cutler, D. M. (2013). Girls’ education and HIV risk: Evidence from Uganda. Journal of Health Economics, 32, 863–872.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Avenstrup, R., Liang, X., & Nellemann, S. (2004). Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi and Uganda: Universal primary education and poverty reduction (Research report). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Bachan, L., & Frye, M. (2013). The decline in non-numeric ideal family size: A cross-regional analysis. Unpublished manuscript, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA and University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA.

Baird, S., Chirwa, E., McIntosh, C., & Ozler, B. (2010). The short-term impacts of a schooling conditional cash transfer program on the sexual behavior of young women. Health Economics, 19, 55–68.

Baird, S., Garfein, R. S., McIntosh, C., & Ozler, B. (2012). Effect of a cash transfer programme for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet, 379, 1320–1329.

Bankole, A., Ahmed, F. H., Neema, S., Ouedraogo, C., & Konyani, S. (2007). Knowledge of correct condom use and consistency of use among adolescents in four countries in sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 11, 197–220.

Bankole, A., & Singh, S. (1998). Couples’ fertility and contraceptive decision-making in developing countries: Hearing the man’s voice. International Family Planning Perspectives, 24, 15–24.

Becker, G. S. (1981). Treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Becker, G. S., & Lewis, H. G. (1973). On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 81, S279–S288.

Bentaouet Kattan, R. (2006). Implementation of free basic education policy (Education Working Paper Series No. 7). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Bentaouet Kattan, R., & Burnett, N. (2004). User fees in primary education (Education for All Working Paper). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Bongaarts, J. (1994). The impact of population policies: Comment. Population and Development Review, 20, 616–620.

Bongaarts, J. (2002). The end of the fertility transition in the developed world. Population and Development Review, 28, 419–443.

Bongaarts, J. (2010). The causes of educational differences in fertility in sub-Saharan Africa (Poverty, Gender, and Youth Working Paper No. 20). New York, NY: The Population Council.

Bongaarts, J., & Watkins, S. C. (1996). Social interactions and contemporary fertility transitions. Population and Development Review, 22, 639–682.

Bulatao, R. A. (1981). Values and disvalues of children in successive childbearing decisions. Demography, 18, 1–25.

Caldwell, J. C. (1976). Toward a restatement of the demographic transition theory. Population and Development Review, 2, 321–366.

Caldwell, J. C. (1980). Mass education as a determinant of the timing of fertility decline. Population and Development Review, 6, 225–255.

Castro Martin, T. (1995). Women’s education and fertility: Results from 26 Demographic and Health Surveys. Studies in Family Planning, 26, 187–202.

Cleland, J., & Wilson, C. (1987). Demand theories of the fertility transition: An iconoclastic view. Population Studies, 41, 5–30.

Coale, A. J. (1973). The demographic transition reconsidered. In Proceedings of the International Population Conference (Vol. 1, pp. 52–72). Liege, Belgium: IUSSP.

Cochrane, S. H. (1979). Fertility and education: What do we really know? (World Bank Staff Occasional Papers No. 26). Baltimore, MD and London, UK: The Johns Hopkins University Press for the World Bank.

Davies, M., & Macdowall, W. (2006). Health promotion theory. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press.

Deininger, K. (2003). Does cost of schooling affect enrollment by the poor? Universal primary education in Uganda. Economics of Education Review, 22, 291–305.

Dewi, R. K., Suryadarma, D., & Suryahadi, A. (2013). The impact of expansion of television coverage on fertility: Evidence from Indonesia (SMERU Working paper). Jakarta, Indonesia: SMERU Research Institute.

Duflo, E., Dupas, P., & Kremer, M. (2012). Education, HIV, and early fertility: Experimental evidence from Kenya. Unpublished manuscript, Economics Department, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, Economics Department, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, and Department of Economics, Harvard University Cambridge, MA.

Dupas, P. (2011). Do teenagers respond to HIV risk information? Evidence from a field experiment in Kenya. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3(1), 1–36.

Easterlin, R. A. (1975). An economic framework for fertility analysis. Studies in Family Planning, 6(3), 54–63.

Easterlin, R. A., & Crimmins, E. (1985). The fertility revolution. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Ferré, C. (2009). Age at first child: Does education delay fertility timing? The Case of Kenya (Policy Research Working Paper No. 4833). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Gallant, M., & Maticka-Tyndale, E. (2004). School-based HIV prevention programmes for African youth. Social Science & Medicine, 58, 1337–1351.

Grogan, L. (2008). Universal primary education and school entry in Uganda. Journal of African Economies, 18, 183–211.

Hansen, L. P. (1982). Large sample properties of generalized method of moments estimators. Econometrica, 50, 1029–1054.

Hayford, S. R. (2009). The evolution of fertility expectations over the life course. Demography, 46, 765–783.

Hayford, S. R., & Agadjanian, V. (2011). Uncertain future, non-numeric preferences and the fertility transition: A case study of rural Mozambique. African Population Studies, 25, 419–439.

Heiland, F., Prskawetz, A., & Sanderson, W. C. (2008). Are individuals’ desired family sizes stable? Evidence from West German panel data. European Journal of Population, 24, 129–156.

Hirschman, C. (1994). Why fertility changes. Annual Review of Sociology, 20, 203–233.

Jensen, R., & Oster, E. (2009). The power of TV: Cable television and women’s status in India. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124, 1057–1094.

Johnson-Hanks, J. (2007). Natural intentions: Fertility decline in the African Demographic and Health Surveys. American Journal of Sociology, 112, 1008–1043.

Kadzamira, E., & Rose, P. (2003). Can free primary education meet the needs of the poor? Evidence from Malawi. International Journal of Educational Development, 23, 501–516.

Knodel, J., & van de Walle, E. (1986). Lessons from the past: Policy implications of historical fertility studies. In A. J. Coale & S. C. Watkins (Eds.), The decline of fertility in Europe: The revised proceedings of a conference on the Princeton European Fertility Project (pp. 390–419). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kravdal, Ø. (2002). Education and fertility in sub-Saharan Africa: Individual and community effects. Demography, 39, 233–250.

La Ferrara, E., Chong, A., & Duryea, S. (2012). Soap operas and fertility: Evidence from Brazil. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4, 1–31.

Lee, R. D. (1980). Aiming at a moving target: Period fertility and changing reproductive goals. Population Studies, 34, 205–226.

Liefbroer, A. C. (2009). Changes in family size intentions across young adulthood: A life-course perspective. European Journal of Population, 25, 363–386.

Lloyd, C. B., Kauffman, C. E., & Hewett, P. (2000). The spread of primary schooling in sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for fertility change. Population and Development Review, 26, 483–515.

Mare, R. D. (1991). Five decades of educational assortative mating. American Sociological Review, 56, 15–32.

Mare, R. D., & Maralani, V. (2006). The intergenerational effects of changes in women's educational attainments. American Sociological Review, 71, 542–564.

Mason, K. O. (1997). Explaining fertility transitions. Demography, 34, 443–454.

McCarthy, J., & Oni, G. A. (1987). Desired family size and its determinants among urban Nigerian women: A two-stage analysis. Demography, 24, 279–290.

McQueston, K., Silverman, R., & Glassman, A. (2013). The efficacy of interventions to reduce adolescent childbearing in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Studies in Family Planning, 44, 369–387.

Method, F., Ayele, T., Bonner, C., Horn, N., Meshesha, A., & Talore Abiche, T. (2010). Impact assessment of USAID’s education program in Ethiopia 1994–2009 (USAID Research Report). Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development.

Moultrie, T. A., & Timaeus, I. M. (2014, May). Rethinking African fertility: The state in, and of, the future sub-Saharan African fertility decline. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Boston, MA.

Mouw, T. (2006). Estimating the causal effect of social capital: A review of the recent research. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 79–102.

Olusanya, P. O. (1971). Status differentials in the fertility attitudes of married women in two communities in Western Nigeria. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 19, 641–651.

Osili, U. O., & Long, B. T. (2008). Does female schooling reduce fertility? Evidence from Nigeria. Journal of Development Economics, 87, 57–75.

Ozier, O. (2010). The impact of secondary schooling in Kenya: A regression discontinuity analysis. Unpublished manuscript, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

Pollak, R. A., & Watkins, S. C. (1993). Cultural and economic approaches to fertility: Proper marriage or mesalliance? Population and Development Review, 19, 467–496.

Pritchett, L. (1994). Desired fertility and the impact of population policies. Population and Development Review, 20, 1–55.

Pritchett, L. (2013). The rebirth of education: Schooling ain’t learning. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Reed, H., Briere, R., & Casterline, J. (Eds.). (1999). The role of diffusion processes in fertility change in developing countries. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Riley, A. P., Hermalin, A. I., & Rosero-Bixby, L. (1993). A new look at the determinants of nonnumeric response to desired family size: The case of Costa Rica. Demography, 30, 159–174.

Ryder, N. B. (1973). A critique of the National Fertility Study. Demography, 10, 495–506.

Ryder, N. B., & Westoff, C. F. (1967). The trend of expected parity in the United States: 1955, 1960, 1965. Population Index, 33, 153–168.

Stock, J. H., Wright, J. H., & Yogo, M. (2002). A survey of weak instruments and weak identification in generalized method of moments. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 20, 518–529.

Thomson, E. (1997). Couple childbearing desires, intentions, and births. Demography, 34, 343–354.

Udry, J. R. (1983). Do couples make fertility plans one birth at a time? Demography, 20, 117–128.

UNESCO. (1990). World declaration on education for all and framework for action to meet basic learning needs. Paris, France: UNESCO.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). (2014). Primary school survival statistics [Database]. Retrieved from http://data.uis.unesco.org/

Watkins, S. C. (1991). From provinces into nations: Demographic integration in Western Europe, 1870–1960. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

World Bank. (2009). Abolishing school fees in Africa: Lessons from Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, and Mozambique (Development Practice in Education report). Washington DC: The World Bank and UNICEF.

Yeatman, S., Sennott, C., & Culpepper, S. (2013). Young women’s dynamic family size preferences in the context of transitioning fertility. Demography, 50, 1715–1737.

Zanin, L., Radice, R., & Marra, G. (2015). Modelling the impact of women’s education on fertility in Malawi. Journal of Population Economics, 28, 89–111.

Acknowledgments

Background support for this study was provided by the grant Team 1000+ Saving Brains: Economic Impact of Poverty-Related Risk Factors for Cognitive Development and Human Capital “0072-03” provided to the Grantee, The Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania by Grand Challenges Canada. I am grateful to Jere Behrman, Lawrence Wu, Delia Baldassarri, Jennifer Jennings, Amber Peterman, Florencia Torche, Paula England, Jennifer Hill, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier versions of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Behrman, J.A. Does Schooling Affect Women’s Desired Fertility? Evidence From Malawi, Uganda, and Ethiopia. Demography 52, 787–809 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0392-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0392-3