Abstract

We take advantage of unique data on specific activities conducted under the Sheppard-Towner Act from 1924 through 1929 to focus on how public health interventions affected infant mortality. Interventions that provided one-on-one contact and opportunities for follow-up care, such as home visits by nurses and the establishment of health clinics, reduced infant deaths more than did classes and conferences. These interventions were particularly effective for nonwhites, a population with limited access to physicians and medical care. Although limited data on costs prevent us from making systematic cost-benefit calculations, we estimate that one infant death could be avoided for every $1,600 (about $20,400 in 2010 dollars) spent on home nurse visits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

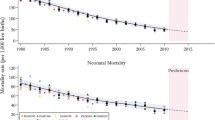

Infant mortality trended strongly downward despite the fact that the BRA continued to expand until 1932 and many of the states that entered later had higher mortality rates than earlier entrants. Figure 1 also plots infant mortality for only those states that were in the BRA as of 1915 to show that the addition of later states does not obscure the strong downward trend. We include this graph to illustrate the trend in infant mortality, but we acknowledge that there are difficulties associated with comparing infant mortality across time, as discussed in Condran and Murphy (2008).

Prior to Sheppard-Towner, the federal government had also provided money to states to assist in venereal disease control and prevention under the Chamberlain-Kahn Act of 1918.

See, for instance, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (2013).

These permanent health centers were not necessarily newly constructed, stand-alone clinics. They often were just regularly scheduled sessions where physicians and nurses would see patients in a given location. For example, some states used rooms in municipal buildings or schools (U.S. Children’s Bureau 1927a:10).

Moehling and Thomasson (2012) discussed evidence of such cost shifting by the states of New Jersey and North Carolina.

We also estimated the model over the periods 1922–1929 and 1915–1929 (excluding the years of the influenza pandemic), making the assumption of zero activity levels for the years prior to 1924. The results were similar to those reported in this article. The degree of cost shifting may have varied across states. As long as states engaged in consistent levels of cost shifting from year to year, the state fixed effects included in the model will account for this variation. However, states may have engaged in different levels of cost shifting from year to year. This would mean that the year-to-year variation in the activity levels reported by the Children’s Bureau could overstate the true variation. Such variable cost shifting would bias the results against finding statistically and economically significant effects of the Sheppard-Towner activities on infant mortality.

We also estimated all models including state income per capita and the number of federal income tax returns filed per capita to capture the effects of rising income and changing income distributions over this period. These data were generously provided by Price Fishback. In none of the estimated models, however, could we reject the hypothesis that these variables had no effect on infant mortality after allowing for state and year fixed effects and state time trends. In addition, the inclusion of these variables did not substantively alter the estimated effects of the Sheppard-Towner activity measures.

As a robustness check, we also estimated models including one-year lags of the Sheppard-Towner activities. The lagged activity measures did not have statistically significant effects on infant mortality rates.

New Jersey was quite open about the fact that it used the federal grants to replace state appropriations. For instance, in 1922, the New Jersey legislature appropriated almost $100,000 less for the Department of Health than it had in 1921. This move was explained in the Department’s annual report in quite plain terms: the appropriations for the Bureau of Child Hygiene and the Bureau of Venereal Disease Control were being reduced because both would be receiving federal monies for their work (New Jersey Department of Health 1922:19).

Another challenge for making comparisons across states when using the Financial Statistics data is the difference in timing of the “fiscal year” for different states. Although most states defined their fiscal year to match that of the federal government, many states used alternative definitions. In fact, in some states, the definition of the “fiscal year” varied across departments (U.S. Census Bureau 1926:13).

To be included in the BRA, a state had to have a systematic procedure in place for recording all births. When the BRA was established in 1915, it consisted of only 10 states. Following is a list of the states that entered the BRA during the study period, along with their years of entry: West Virginia (1925); Arizona (1926); Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Missouri, and Tennessee (1927); Colorado, Georgia, and Oklahoma (1928); and Nevada and New Mexico (1929). South Carolina was part of the BRA in 1924, was dropped in 1925, and then was readmitted in 1928. The two states not part of the BRA by 1929 were South Dakota and Texas (Linder and Grove 1947:97).

We also estimated all models using the balanced panel consisting of states in the BRA for all five years; the basic findings did not change. All estimated models we present in this article include the three states that did not participate in Sheppard-Towner: Connecticut, Illinois, and Massachusetts. Excluding these states does not alter the basic findings.

The widening of the racial gap in infant mortality later in the twentieth century can be attributed to the fact that whites had better access to improved medical care than blacks (see Almond et al. 2006).

We also cannot discount the possibility of selection bias; mothers who were more aware of the value of hygiene may have been more likely than other mothers to attend child health conferences.

In results not presented, we found that the impact of prenatal letters was most pronounced in states with larger rural populations, suggesting that women with limited access to medical care benefited most from this type of intervention.

If such a bias exists, it would mean our estimates of the effects of Sheppard-Towner activities are understated.

References

Aiyer, S., Jamison, D. T., & Londoño, J. L. (1995). Health policy in Latin America: Progress, problems, and policy options. Cuadernos de Economia, 32, 11–28.

Almond, D., Chay, K. Y., & Greenstone, M. (2006). Civil rights, the War on Poverty, and black-white convergence in infant mortality in the rural South and Mississippi (MIT Department of Economics Working Paper No. 07-04). Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Anand, S., & Ravallion, M. (1993). Human development in poor countries: On the role of private incomes and public services. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7, 133–150.

Anyanwu, J. C., & Erhijakpor, A. E. O. (2009). Health expenditures and health outcomes in Africa. African Development Review, 21, 400–433.

Apple, R. D. (2006). Perfect motherhood: Science and childrearing in America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Apple, R. D. (2011). To avoid expense and suffering: Public health nurses and the struggle for health services. In P. D’Antonio & S. B. Lewenson (Eds.), Nursing interventions through time: History as evidence (pp. 173–188). New York, NY: Springer.

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. (2013). Maternal, neonatal, and child health: Strategy overview. Retrieved from http://www.gatesfoundation.org/What-We-Do/Global-Development/Maternal-Neonatal-and-Child-Health

Condran, G. A., & Murphy, J. (2008). Defining and managing infant mortality. Social Science History, 32, 473–513.

Cutler, D., & Miller, G. (2005). The role of public health improvements in health advances: The twentieth century United States. Demography, 42, 1–22.

Dart, H. M. (1921). Maternity and child care in selected rural areas of Mississippi (U.S. Children’s Bureau Publication No. 88). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Ferrie, J. P., & Troesken, W. (2008). Water and Chicago’s mortality transition, 1820–1925. Explorations in Economic History, 45, 1–16.

Filmer, D., Hammer, J., & Pritchett, L. (1998). Health policy in poor countries: Weak links in the chain (Policy Research Working Paper No. 1874). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. (1997). Child mortality and public spending on health: How much does money matter? (Policy Research Working Paper No. 1864). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Fogel, R. W. (1994). Economic growth, population theory, and physiology: The bearing of long-term processes on the making of economic policy. American Economic Review, 84, 369–395.

Fox, J. (2011). Public health movements, local poor relief and child mortality in American cities: 1923–1932 (MPIDR Working Paper WP 2011-005). Rostock, Germany: Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research.

Grossman, M. (1972). On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. Journal of Political Economy, 80, 223–255.

Gupta, S., Verhoeven, M., & Tiongson, E. R. (2002). The effectiveness of government spending on education and health care in developing and transition economies. European Journal of Political Economy, 18, 717–737.

Haines, M. R. (2001). The urban mortality transition in the United States, 1800–1940 (NBER Working Paper on Historical Factors in Long Run Growth No. 134). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hojman, D. E. (1996). Economic and other determinants of infant and child mortality in small developing countries: The case of Central America and the Caribbean. Applied Economics, 28, 281–290.

Journal of the American Medical Association. (1932). Federalization of health and hygiene through Sheppard-Townerism [editorial]. Journal of the American Medical Association, 98, 404–405.

Kim, K., & Moody, P. M. (1992). More resources better health? A cross-national perspective. Social Science & Medicine, 34, 837–842.

Ladd-Taylor, M. (1988). “Grannies” and “spinsters”: Midwife education under the Sheppard-Towner Act. Journal of Social History, 22, 255–275.

Ladd-Taylor, M. (1994). Mother-work: Women, child welfare, and the state, 1890–1930. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Lemons, J. S. (1969). The Sheppard-Towner Act: Progressivism in the 1920s. Journal of American History, 55, 776–786.

Lemons, J. S. (1990). The woman citizen: Social feminism in the 1920s. Charlottesville: The University of Virginia Press.

Lindenmeyer, K. (1997). A right to childhood: The U.S. Children’s Bureau and child welfare, 1912–1946. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Linder, F. E., & Grove, R. D. (1947). Vital statistics rates in the United States 1900–1940. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Lott, J. R., Jr., & Kenny, L. W. (1999). Did women’s suffrage change the size and scope of government? Journal of Political Economy, 107, 1163–1198.

McGuire, A., Parking, D., Hughes, D., & Gerard, K. (1993). Econometric analyses of national health expenditures: Can positive economics help answer normative questions? Health Economics, 2, 113–126.

McKeown, T. (1976). The modern rise of population. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Meckel, R. A. (1990). Save the babies: American public health reform and the prevention of infant mortality, 1850–1929. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Miller, G. (2008). Women’s suffrage, political responsiveness, and child survival in American history. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123, 1287–1327.

Moehling, C. M., & Thomasson, M. A. (2012). The political economy of saving mothers and babies: The politics of state participation in the Sheppard-Towner program. Journal of Economic History, 72, 75–103.

Musgrove, P. (1996). Public and private roles in health: Theory and financing patterns (World Bank Discussion Paper No. 339). Washington, DC: World Bank.

New Jersey Department of Health. (1922). Annual report. Trenton: State of New Jersey.

Ohio Director of Finance. (1927). Executive budget of Ohio, 1927–1928. Columbus, OH: The F.J. Heer Printing Co.

Paradise, V. (1919). Maternity care and the welfare of young children in a homesteading county in Montana (U.S. Children’s Bureau Publication No. 34). Washington, DC: Governmental Printing Office.

Selden, C. A. (1922). The most powerful lobby in Washington. Ladies Home Journal, 39, 95.

Sherbon, F. B., & Moore, E. (1919). Maternity and infant care in two rural counties in Wisconsin (U.S. Children’s Bureau Publication No. 46). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Skocpol, T. (1994). Protecting soldiers and mothers: The political origins of social policy in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Smith, D. B. (1999). Health care divided: Race and healing a nation. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Thomasson, M. A., & Treber, J. (2008). From home to hospital: The evolution of childbirth in the United States, 1928–1940. Explorations in Economic History, 45, 76–99.

Troesken, W. (2004). Water, race, and disease. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

U.S. Census Bureau. (1922). Fourteenth census of the United States taken in the year 1920. Volume II. Population. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Census Bureau. (1925–1930). Financial statistics of states. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Children’s Bureau. (1917). Fifth annual report of the Chief, Children’s Bureau to the Secretary of Labor. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Children’s Bureau. (1925). The promotion of the welfare and hygiene of maternity and infancy (Bureau Publication 146). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Children’s Bureau. (1926a). The promotion of the welfare and hygiene of maternity and infancy (Bureau Publication 156). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Children’s Bureau. (1926b). Proceedings of the third annual conference of state directors in charge of the local administration of the Maternity and Infancy Act (Bureau Publication 157). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Children’s Bureau. (1927a). The promotion of the welfare and hygiene of maternity and infancy (Bureau Publication 178). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Children’s Bureau. (1927b). Proceedings of the fourth annual conference of state directors in charge of the local administration of the Maternity and Infancy Act (Bureau Publication 181). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Children’s Bureau. (1928). The promotion of the welfare and hygiene of maternity and infancy (Bureau Publication 186). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Children’s Bureau. (1929). The promotion of the welfare and hygiene of maternity and infancy (Bureau Publication 194). Washington, DC: Governmental Printing Office.

U.S. Children’s Bureau. (1931a). The seven years of the Maternity and Infancy Act. Washington, DC: Governmental Printing Office.

U.S. Children’s Bureau. (1931b). The promotion of the welfare and hygiene of maternity and infancy (Bureau Publication 203). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Woodbury, R. M. (1925). Causal factors in infant mortality: A statistical study based on investigations in eight cities. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank seminar participants at the 2011 Cliometric Society meetings, the University of Colorado, the University of Michigan, the University of Chicago, and Chapman University. The authors assume all responsibility for any errors or omissions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moehling, C.M., Thomasson, M.A. Saving Babies: The Impact of Public Education Programs on Infant Mortality. Demography 51, 367–386 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0274-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0274-5