Abstract

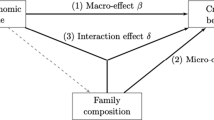

Other researchers have posited that important events in men’s lives—such as employment, marriage, and parenthood—strengthen their social ties and lead them to refrain from crime. A challenge in empirically testing this hypothesis has been the issue of self-selection into life transitions. This study contributes to this literature by estimating the effects of an exogenous life shock on crime. We use data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, augmented with information from hospital medical records, to estimate the effects of the birth of a child with a severe health problem on the likelihood that the infant’s father engages in illegal activities. We conduct a number of auxiliary analyses to examine exogeneity assumptions. We find that having an infant born with a severe health condition increases the likelihood that the father is convicted of a crime in the three-year period following the birth of the child, and at least part of the effect appears to operate through work and changes in parental relationships. These results provide evidence that life events can cause crime and, as such, support the “turning point” hypothesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The oversampling of nonmarital births solely in urban areas resulted in a sample that, generally, is more disadvantaged than the general population. See Reichman et al. (2001) for a description of the research design.

Access to the medical records reflected, to a large extent, administrative decisions of the different hospitals rather than decisions on the part of individual respondents to have their records reviewed.

Of course, individuals can be convicted of crimes that they did not commit, or can be arrested and incarcerated before trial and then ultimately acquitted or have the charges dropped. Such cases would result in false positives for convictions and incarcerations, respectively.

Although the turning point literature focuses on the long-term trajectory of criminal activity, the effects of life events on crime appear to occur rather quickly. For example, Laub et al. (1998) found that by three to four years of married life, arrest rates are 52.5% lower for men in strong marriages than for unmarried men, and that the difference increases only minimally over the next two years (to 53.8%) and then tapers off quickly. Thus, our three-year time horizon seems reasonable.

Compared with the men in our sample, the men not in the sample were significantly less likely to have been married to their child’s mother, less likely to have been in a relationship with the mother for at least 12 months, less likely to have visited the mother and child in the hospital, less likely to have lived with both parents at age 15, and more likely to be non-Hispanic black.

Small cell sizes and incomplete data on types of crime preclude separate analyses by type of crime.

The following questions were used from the fathers’ follow-up surveys to determine whether the father had ever been convicted after the birth of the child and whether the father had ever been convicted before the birth of the child: (1) “Have you ever been convicted of any charges?” (2) “How old were you (the first time/when) this happened?” (3) “When was your most recent conviction?”

The incarceration questions asked of fathers in the follow-up surveys were similar to those for conviction (see footnote 8). The questions asked of mothers about the fathers’ incarceration history were similar in structure to those asked of fathers. We used fathers’ reports when they were available and mothers’ reports otherwise. Fathers’ reports were used for 2,469 of the 2,677 cases in the analysis sample for incarceration. There were only 18 cases in which the father reported that he had never been incarcerated but the mother gave conflicting information, and the estimates were insensitive to the coding of those cases. The high level of agreement between the father and mother reports of incarceration and the insensitivity of our estimates are validating of our incarceration measure. Additional details about the construction of both the incarceration and conviction measures are available upon request.

It is possible that judges are less willing to incarcerate convicted fathers with unhealthy children than to incarcerate convicted fathers with healthy children. We know of no evidence on this, but if this is the case, it would result in underestimated effects of poor infant health on crime using the incarceration measure. This potential scenario underscores the value in considering conviction as an alternative proxy for crime.

All but two of the infants with very low birth weight also had moderately severe infant health conditions, which are defined as conditions not considered to be related to maternal behavior that may or may not have long-term health consequences.

Because there is neither a standard for measurement nor a consistent reporting of child disability (Reichman et al. 2008), it is difficult to provide a good national comparison for our figures. Our rates of poor infant health are consistent with the range of 6% to 18% of children in the United States that have special health care needs, as reported by Stein (2005). It is not unexpected that our strictest measure is lower than this range, since that measure includes only very serious conditions and excludes conditions that are known to be related to maternal behaviors. Likewise, it is not unexpected that our broadest measure is slightly higher than the upper-bound estimate, since it is defined to include conditions that are not necessarily disabling in the long run.

Because of high collinearity between mothers’ and fathers’ ages, race/ethnicity, and education, these measures are expressed as differences from the father.

Considering the characteristics of our sample, our unadjusted race-specific rates of conviction and incarceration are consistent with racial differences in crime observed at the national level. For example, in 2005, about 28% of all arrests in the United States were to blacks, who made up about 14% of the U.S. population (U.S. Department of Justice 2006). In our sample, 24% of non-Hispanic black fathers and 18% of non-Hispanic white fathers had been convicted of a crime before the focal child’s birth, and 18% of non-Hispanic black fathers and 9% of non-Hispanic white fathers had been incarcerated before the focal child’s birth.

We also ran a set of “falsification tests” that estimated pre-birth criminal activity as a function of poor infant health and the other covariates. The logic was that a shock that takes place at the time of the birth cannot possibly affect the father’s pre-birth criminal activity, and finding significant associations would indicate spurious correlation. These models are essentially equivalent to the models of poor infant health as a function of pre-birth criminal behavior, except that the dependent and independent variables were reversed. As expected, we found that poor infant health was an insignificant predictor of pre-birth crime in all cases except when using low birth weight and predicting incarceration.

See Reichman et al. (2009) for more detail on the construction of the smoking, drug use, and prenatal care measures, which incorporated medical records and survey data. The alcohol measure was constructed using the same methodology as for the smoking and drug use variables.

We do not know whether the men in our sample were convicted (or incarcerated) for a misdemeanor or for a felony. We would expect the processing time to be shorter for misdemeanors.

The interactions were statistically significant at conventional levels in half of the cases. They were most consistently significant (across measures of poor infant health and outcomes) for unemployed and having prior criminal activity.

Exceptions are for living with the mother at one year, for which p values range from .09 to .18.

References

Becker, G. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76, 169–217.

Butcher, K. F., & Piehl, A. M. (1998). Recent immigrants: Unexpected implications for crime and incarceration. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 51, 654–679.

Butcher, K. F., & Piehl, A. M. (2007). Why are immigrants’ incarceration rates so low? Evidence on selective immigration, deterrence, and deportation (NBER Working Paper No. 13229). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Caceres-Delpiano, J., & Giolito, E. (2008). The impact of unilateral divorce on crime (IZA Discussion Paper No. 3380). Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Capaldi, D. M., Kim, H. K., & Owen, L. D. (2008). Romantic partners’ influence on men’s likelihood of arrest in early adulthood. Criminology, 46, 267–299.

Corman, H., Noonan, K., & Reichman, N. E. (2005). Mothers’ labor supply in fragile families: The role of child health. Eastern Economic Journal, 31, 601–616.

Dahl, G. B., & Moretti, E. (2008). The demand for sons. Review of Economic Studies, 75, 1085–1120.

Duncan, G. J., Wilkerson, B., & England, P. (2006). Cleaning up their act: The effects of marriage and cohabitation on licit and illicit drug use. Demography, 43, 691–710.

Edin, K., & Reed, J. M. (2005). Why don’t they just get married? Barriers to marriage among the disadvantaged. The Future of Children, 15, 117–137.

Edin, K., Nelson, T. J., & Paranal, R. (2004). Fatherhood and incarceration as potential turning points in the criminal careers of unskilled men. In M. Pattillo, D. Weiman, & B. Western (Eds.), Imprisoning America: The social effects of mass incarceration (pp. 46–75). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Edlund, L., Li, H., Yi, J., & Zhang, J. (2007). Sex ratios and crime: Evidence from China’s one-child policy (IZA Discussion Paper No. 3214). Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Ehrlich, I. (1973). Participation in illegitimate activities: A theoretical and empirical investigation. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 521–565.

Freeman, R. B. (1996). Why do so many young American men commit crimes and what might we do about it? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10, 461–488.

Geller, A., Garfinkel, I., Cooper, C., & Mincy, R. (2009). Parental incarceration and child wellbeing: Implications for urban families. Social Science Quarterly, 90, 1186–1202.

Gould, E. D., Weinberg, B. A., & Mustard, D. B. (2002). Crime rates and local labor market opportunities in the United States 1979–1997. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84, 45–61.

Grogger, J. (1998). Market wages and youth crime. Journal of Labor Economics, 16, 756–791.

Horney, J., Osgood, W., & Marshall, I. H. (1995). Criminal careers in the short-term: Intra-individual variability in crime and its relation to local life circumstances. American Sociological Review, 60, 655–673.

Kerner, H.-J. (2005). The complex dynamics of the onset, the development, and the termination of a criminal career: Lessons on repeat offenders to be drawn from recent longitudinal studies in criminology. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 602, 259–279.

King, R. D., Massoglia, M., & MacMillan, R. (2007). The context of marriage and crime: Gender, the propensity to marry, and offending in early adulthood. Criminology, 45, 33–65.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (1993). Turning points in the life course: Why change matters to the study of crime. Criminology, 31, 301–325.

Laub, J. H., Nagin, D. S., & Sampson, R. J. (1998). Trajectories of change in criminal offending: Good marriages and the desistance process. American Sociological Review, 63, 225–238.

Lochner, L., & Moretti, E. (2004). The effect of education on crime: Evidence from prison inmates, arrests, and self-reports. American Economic Review, 94, 155–189.

McLanahan, S., Garfinkel, I., Reichman, N. E., Teitler, J. O., Carlson, M., & Norland Audigier, C. (2003). The fragile families and child wellbeing study: Baseline national report (revised March 2003). Princeton, NJ: Center for Research on Child Wellbeing. Retrieved from http://www.fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/documents/nationalreport.pdf

Mocan, N., & Rees, D. I. (2005). Economic conditions, deterrence and juvenile crime: Evidence from micro data. American Law and Economics Review, 7, 319–349.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2011). Health, United States, 2010 with special feature on death and dying. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus.htm

Noonan, K., Reichman, N. E., & Corman, H. (2005). New fathers’ labor supply: Does child health matter? Social Science Quarterly, 86, 1399–1417.

Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P., & Blumstein, A. (2003). The criminal career paradigm. Crime and Justice, 30, 359–506.

Raphael, S. (2007). Early incarceration spells and the transition to adulthood. In S. Danziger & C. E. Rouse (Eds.), The price of independence: The economics of early adulthood (pp. 278–306). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Reichman, N. E. (2005). Low birth weight and school readiness. The Future of Children, 15, 91–116.

Reichman, N. E., Teitler, J. O., Garfinkel, I., & McLanahan, S. (2001). Fragile Families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review, 23, 303–326.

Reichman, N. E., Corman, H., & Noonan, K. (2004). Effects of child health on parents’ relationship status. Demography, 41, 569–584.

Reichman, N. E., Corman, H., & Noonan, K. (2006). Effects of child health on sources of public support. Southern Economic Journal, 73, 136–156.

Reichman, N. E., Corman, H., & Noonan, K. (2008). Impact of child disability on the family. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 12, 679–683.

Reichman, N. E., Corman, H., Noonan, K., & Dave, D. M. (2009). Infant health production functions: What a difference the data make. Health Economics, 18, 761–782.

Saluter, A. F. (1994). Marital status and living arrangements: March 1994 (Current Population Reports, Series P20-484). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p20-484.pdf

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1990). Crime and deviance over the life course: The salience of adult social bonds. American Sociological Review, 55, 609–627.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1996). Socioeconomic achievement in the life course of disadvantaged men: Military service as a turning point, circa 1940–1965. American Sociological Review, 61, 347–367.

Sampson, R. J., Laub, J. H., & Wimer, C. (2006). Does marriage reduce crime? A counterfactual approach to within-individual causal effects. Criminology, 44, 465–508.

Sickles, R. C., & Williams, J. (2008). Turning from crime: A dynamic perspective. Journal of Econometrics, 145, 158–173.

Stein, R. E. K. (2005). Trends in disability in early life. In M. J. Fields, A. M. Jerre, & L. Marin (Eds.), Workshop on disability in America: A new look (pp. 143–156). Washington, DC: The National Academies.

The Cost of Crime: Understanding the Financial Impact of Criminal Activity: Testimony before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 109th Cong. 4 (2006). (testimony of Jeffery Sedgwick).

U.S. Census Bureau. (2009). America’s families and living arrangements: 2008. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hh-fam/cps2008.html

U.S. Department of Justice. (2004). Felony sentences in state courts, 2002 (Bulletin NCJ 206916). Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Verbrugge, L. M. (1982). Sex differentials in health. Prevention, 97, 417–437.

Wildeman, C. (2009). Parental imprisonment, the prison boom, and the concentration of childhood disadvantage. Demography, 46, 265–280.

Wildeman, C. (2010). Paternal incarceration and children’s physically aggressive behaviors: Evidence from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. Social Forces, 89, 285–309.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grants R01-HD-45630 and R01-HD-35301 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. We are grateful for helpful input from Jerry Bentley, Naci Mocan, Alan Monheit, Melinda Pitts, Joy Schneer, and the participants at the economic seminar series at Lafayette College and the University of Medicine and Dentistry School of Public Health, and for valuable assistance from Magdalena Ostatkiewicz, Nicole Boynton, and Prisca Figaro.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Coding of Measures of Poor Infant Health

Appendix: Coding of Measures of Poor Infant Health

The coding of abnormal conditions was designed to identify cases that were at least moderately severe, were not likely caused by prenatal behavior, had a poor long-term prognosis, and were present at birth. A pediatric consultant was directed to glean information from the medical records (augmented with one-year maternal reports) and to assign all infant conditions a number between 1 and 16 according to the grid shown in Table 5. After giving the consultant the grid and clear instructions, the authors had no further input into how particular conditions were coded. If a child had multiple conditions, each condition was assigned a separate number. Very severe infant health condition was coded as 1 (yes) if the child had a health condition in cell 1. Examples of conditions in cell 1 are microcephalus, renal agenesis, total blindness, and Down syndrome.

Severe infant health condition was coded as 1 (yes) if the child had a condition in cell 1 or the child was very low birth weight (less than 1,500 grams).Any infant health condition was coded as 1 (yes) if the child had a condition in either cell 1 or cell 2. Examples of conditions in cell 2, which are considered random at birth but may or may not have long-term health consequences, are malformed genitalia, hydrocephalus, cleft palate, shoulder dystocia, pneumomediastinum, and webbed fingers or toes.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Corman, H., Noonan, K., Reichman, N.E. et al. Life Shocks and Crime: A Test of the “Turning Point” Hypothesis. Demography 48, 1177–1202 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0042-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0042-3