Abstract

The design and development of appropriate regulatory mechanisms have attracted renewed attention in recent years. In particular, a shift towards voluntary self-regulatory mechanisms has been witnessed within many industries, such as the Australian mining and petroleum industries which have developed voluntary codes of conduct. This paper analyses the development of different regulatory forms and provides a brief comparative analysis of the two main voluntary codes of conduct used by the Australian mining and petroleum industries. In particular, the study focuses on the integration of social sustainability elements within these frameworks that help contribute to solving issues such as coverage of human rights, approaches to employee and community relations, systems of stakeholder engagement, community consultation and public reporting. The study concludes that stakeholders have an important role to play in driving the introduction of voluntary regulation. This phenomenon can be traced back to how a company’s need to maintain its legitimacy, or social licence to operate, often motivates it to go beyond compliance. By providing a fuller understanding of factors driving the evolution of different regulatory mechanisms, this study has important implications for policy makers and practitioners interested in developing effective regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The changing regulatory landscape has seen an evolution in regulatory forms from traditional command and control regulation to more flexible, principle-based, voluntary forms of regulation (Parker 2008; Posner 2007; Steinzor 1998). Given the vast complexity of regulatory laws (Hickman and Hill 2010), the limitations of prescriptive, complex, and often ambiguous command and control regulation are becoming increasingly apparent (Steinzor 1998; Stewart 1995). Command and control regulation (which often takes the form of setting minimum impact standards, or permits and licences), often provides incentives for corporations to achieve the minimum standard and does not motivate a corporation to achieve continuous improvement (Gunningham et al. 1998; Sinclair 1997). The limitations of traditional regulatory forms motivated a search for new, more flexible regulatory methods.

Self-regulation, with its promise of industry cooperation and win–win outcomes, has attracted much attention over recent years (Baron 2010; Steinzor 1998) as a means to avoid the pitfalls of direct regulation at lower cost (Sinclair 1997). However, the widely acknowledged pitfall of self-regulation (Steinzor 1998) is that purely voluntary initiatives lack appropriate incentives to comply. It is for this reason that most regulatory instruments used fall somewhere between command and control and purely voluntary. According to Parker (2008), this means we are entering into a new age of regulatory pluralism, where self-regulation works alongside government enforcement, often to achieve a hybrid regulatory form known as co-regulation. Gunningham et al. (1998) argue that co-regulation offers the best of both worlds: the flexibility and continuous improvement of self-regulation and the motivation to comply of command and control regulation. The pioneering work of Ayres and Braithwaite (1992; who developed the regulatory pyramid) caused a rethink of the traditional role of the regulator. Instead of merely monitoring and punishing breaches of regulations, the role of the regulator was reconceptualised as encouraging voluntary compliance, with sanctions reserved for those at the top of the pyramid who remained unwilling to comply (Braithwaite 2006). Despite these developments, there is still no consensus on the best regulatory mix to use in every circumstance, although Gunningham et al. (1998) suggest some guidance.

Very few studies have looked at the effectiveness of self-regulatory initiatives, such as the voluntary codes of conduct, in improving corporate performance on the ground (Puplampu and Dashwood 2011; Barkay 2009). This is particularly important for environmentally and socially disruptive sectors such as the mining and petroleum industries, which not only have a track record of poor corporate social responsibility (CSR) standards, but whose failure to uphold good CSR standards cause long-term social, environmental and economic harm (Pennington and More 2010). While voluntary regulatory instruments have a clear and observable effect in improving accountability and self-governance in other industry sectors (see, e.g. Furger 1997), there is little evidence of the role of such instruments in the contexts of mining and petroleum industries. This study aims to fill this gap.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. The following section provides a brief analysis of the impacts that the mining and petroleum industries have on communities and the environment. It then proceeds to look at the evolution different forms of regulation in the context of the Australian mineral and petroleum industries that can help mitigate and resolve such issues. An analysis of the role stakeholders play in driving the development of different regulatory mechanisms is included. The section “Maintaining organisational legitimacy: does it matter to the Australian mineral and petroleum industries?” analyses the way in which corporations and regulation responds to a legitimacy crisis, where the company or industry has breached its social licence to operate and must respond accordingly. The final section offers some concluding remarks.

Mining, petroleum and social issues

In the context of Australia mining, until the 1990s the political economy of mineral development in Australia left Aboriginal people marginalised, denying them a say over mining on their traditional lands, excluding them from the benefits of development and leaving them to bear many of its social and environmental costs. For example, uranium mining in the Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory of Australia has a long and controversial history. It has since been alleged that the Mirrar people were intimidated, bullied and bribed into signing over land rights for the mine. The situation is further complicated as the Mirrar people have been led to believe that they need the Ranger Mine to stay open as they rely on the royalty payments and the provision of financial support for community services and health care that come from the mine (Jenkins 2004). This introduces the notion of ‘false dependency’, allowing the company to position themselves as providers of much needed resources that the Mirrar could not get elsewhere; constantly undermining the strength and autonomy of the community by reinforcing their dependency on the company. In this sense, community development programmes provided by mining companies could be viewed not as ‘socially responsible’ but as a means of controlling the community (Jenkins 2004).

Attempts by the mining industry to apply sustainable development principles in practice remain the subject of much debate, with little agreement as to whether mining can ever be compatible with a sustainability agenda (Fitzpatrick et al. 2011). Scholars such as Whitmore (2006) remain critical of sustainable mining initiatives, arguing that the mining industry’s attempt to “greenwash itself as a new, improved, sustainable industry” (p. 313) has not been substantiated by any meaningful change in activities or ambition. In light of these tensions, accountability for social performance in mining becomes pivotal.

Evolution of regulatory framework mechanisms

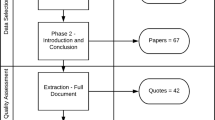

Although there is a diverse range of regulatory mechanisms commonly used by industries, they can all generally be categorised into four main groups: command and control, voluntarism, self-regulation, and co-regulation. While each of these regulatory mechanisms has different strengths and weaknesses, what is common among them is that they each deal with a relationship between the government, the industry association and the individual organisation. As such, any regulatory arrangement can be conceptualised as a regulatory triangle involving interactions between these three parties (Sarker 2008). This is shown in Fig. 1 below.

Command and control regulation occurs when the state directly intervenes in the market and mandates particular corporate behaviour. Such command and control regulation takes a number of forms, including the government establishing a set of universal standards, issuing permits or licences, or entering into a covenant or undertaking with the organisation in question (Gunninghman and Sinclair 1998). As Fig. 1 shows, in command and control regulation, the government directly influences firms’ activities through rules and legislation (administered through regulatory bodies). Assuming that the government is composed of individuals motivated by a desire to serve the public by doing what is “right”, the government will impose command and control regulation on the basis of public interest or public pressure (Sarker 2008). By contrast, voluntarism is based on the belief that the individual firm unilaterally undertakes to do the right thing. This may involve the government playing the role of facilitator and co-ordinator (Gunninghman and Sinclair 1998; Fallon 2009; Barkay 2009). Sinclair (1997) posits that a complete absence of any compulsion to comply is rare, given they are usually adopted in response to peer pressure, or in an effort to avoid more formal regulation (Sinclair 1997; Gunningham et al. 1998). Another method is self-regulation, which can be described as the process in which an organised group regulates the behaviour of its members (OECD 1994). The industry organisation may act as a surrogate regulatory body by monitoring or policing the industry codes of conduct as a complement or alternative to government regulation (Gunningham et al. 1998). Negotiated agreements may also be concluded between the government regulator and the industry association (Sarker 2005). Self-regulation usually takes one of three forms. First, voluntary self-regulation involves an industry or profession establishing codes of practice, enforcement mechanisms, and other methods for regulating itself entirely independent of government. Second, mandated self-regulation is where the state requires the business to establish controls over its own behaviour, but leaves the details and enforcement to business itself, which is subject to state approval or oversight. Finally, mandatory partial self-regulation involves business being responsible for some of the rules and their enforcement, but with the overriding regulatory specifications being mandated by the state (Gunninghman and Sinclair 1998).

Examples of current self-regulatory initiatives in the Australian mining and extractive industries are the Enduring Value Framework (EVF), developed by the Minerals Council of Australia (MCA) for mining companies and the Principles of Conduct and Code and Environmental Practice (PCCEP) developed by the Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association (APPEA) for the oil and gas sector. This is an example of self-regulation because the industry association (MCA or APPEA) has developed a code of conduct for its members. The MCA and APPEA may be considered to act as surrogate regulatory organisations, although their monitoring and enforcement abilities are limited. Adoption of the EVF is a condition of MCA membership and the MCA may withdraw membership for persistent and continuing non-compliance. To date, no withdrawals have been made (Sarker and Gotzmann 2009). By contrast, adoption of the PCCEP is not contingent on APPEA membership, and hence there is no sanction for non-compliance.

Finally, co-regulation is another model proposed by Gunningham (1998) which he defines as the existence of a degree of government regulation in combination with the self-initiated safeguards introduced by the industry organisation. Under the model, minimum outcome-based standards would continue to be set by the government, and the government would reserve the right to impose legal sanctions for breach where enterprises fail to live up to their promises. However, the daily administration of these standards would be the responsibility of industry, subject to community scrutiny and third party audit. The government intervention prevents free riding, while appropriate incentives are provided for organisations to engage in a process of continuous improvement (Gunningham 1998).

Commonly placed under the banner of co-regulation are multi-stakeholder instruments stemming from hybrid mechanisms created by civil society, business, government and intergovernmental organisations (Albareda 2008) and public–private partnerships. It also covers the case where business and intergovernmental organisations work together to create standards, such as the United Nations Global Compact or the European Alliance for CSR. It also includes partnerships between business and non-governmental organisations, such as the Forest Stewardship Council, the Social Accountability International Standard SA8000, and global public policy networks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (Albareda 2008).

When deciding what regulatory mechanism to use, there are a number of considerations that must be taken into account, including the nature of the industry, the nature of the conduct wished to be prohibited, and the alignment of corporate interests with the public interest (Gunningham et al. 1998). The object of regulation should not only be to set minimum standards of conduct and achieve a minimum level of compliance, but for corporations to continually improve their behaviour, and go beyond compliance in all instances. This is difficult in practice, since the traditional view of corporate compliance is one grounded in self-interest (Hickman and Hill 2010). Many self-regulatory initiatives may be considered as having been adopted in order to avoid command and control regulation (Sarker and Gotzmann 2009) and restore legitimacy to a reputationally damaged industry. This is demonstrated in Fig. 2 below.

Pros and cons of various regulatory mechanisms

Each form of regulation has different pros and cons and hence may be suitable for a different regulatory task (Gunningham et al. 1998). The major benefit of command and control regulation is its certainty: firms and regulators have a clear understanding of their regulatory obligations. However, this heavy regulation may elicit resistance (Gunninghman and Sinclair 1998), and at best, often does not motivate organisations to engage in anything more than a minimum level of compliance and evasion where possible (Hickman and Hill 2010). Furthermore, it is also generally considered rigid, complex and often economically inefficient. Plus, it relies on adequate levels of monitoring and enforcement by the regulator (Gunninghman and Sinclair 1998; Sarker 2008). Voluntarism, on the other hand, is non-interventionist, has high industry acceptability and raises minimal equity concerns. It works best where private self-interest coincides with the broader public interest (Gunninghman and Sinclair 1998).

Self-regulation refers to the mechanisms used by companies or organisations, both individually and in conjunction with others, to raise and maintain standards of corporate conduct (Brereton 2002). The benefit of self-regulation is that it offers greater speed, flexibility, sensitivity to market circumstances, efficiency and less government intervention than command and control regulation. This is primarily because standard setting is the responsibility of practitioners who have expert knowledge of the industry. However, the major problem with self-regulation is that it commonly serves the knowledge of the industry, rather than the public (Gunninghman and Sinclair 1998). It is for this reason that it is often criticised as giving the appearance of regulation while serving private interests at the expense of the public (Braithwaite 1993; Gunninghman and Sinclair 1998). Nonetheless, there is a significant body of literature that finds self-regulation as more effective than command and control regulation in getting managers to act more proactively, rather than reactively (May 2003; Newman and Bach 2004; Sarker 2008).

Co-regulation on the other hand has additional advantages of providing greater flexibility, giving industry ownership of the solution, and of avoiding much of the culture of resistance that may accompany government regulation (Gunninghman and Sinclair 1998). Gunningham (1998) argues that co-regulation has the potential to achieve continuous improvement in environmental performance and take enterprises beyond compliance with existing regulation. However, enforcement may be problematic and industry organisations may be unwilling to cede regulatory power to the state. It is worth noting that the principle of accountability in CSR provides an important conceptual linkage between the current risk paradigm, and the notion of ‘self-regulation’; the former reflecting a concern for corporate reputation through the well-known ‘audit’ process, with the latter denoting a decidedly more ideal approach in which companies self-direct along agreed values and expectations (Kemp et al. 2012).

The apparent gap between CSR policies endorsed by some companies and their level of compliance with the standards set out in those policies inevitably raises questions about the value of regulation of this sort. The weakness of much of the international and national indexes and other soft regulation that forms the base for most CSR focus lies not merely in its voluntary form. CSR is most commonly critiqued for the fact that its voluntary nature leads to uneven application of CSR practices as well as for its lack of definitional precision and poor measurement (Van Oosterhout and Heugens 2006). In mining, it is clear that this uneven application of CSR prevails across the sector but also within particular corporations across their global operations, depending on local circumstances, and even at the project level (Coumans 2010). A mine manager may be applying best practice with regard to environmental practices while human rights abuses by security guards go unaddressed.

The reputational damage to the minerals and petroleum sectors occurred alongside the growth of international sustainability initiatives such as the United Nations Rio Declaration and Agenda 21 (Brereton 2002; Schiavi 2005), and the improved legal recognition of Indigenous land rights (Brereton 2002). Given the above, it is consistent with regulatory theory to view the voluntary codes of conduct as having been adopted to restore legitimacy to the industries and help restore their damaged reputation (Gunningham et al. 1998). This is because when a company fails to maintain its social licence to operate, not only does it run the risk of damaging its reputation and incurring command and control regulation, but it also risks losing its legitimacy. Adoption of voluntary codes of conduct can thus be an important way to restore the legitimacy in organisations (Gunningham et al. 1998).

Oil spills, or the recent unrest spreads in South Africa that police shot dead 34 striking workers in Marikana mine, emphasise on the importance of these self-regulatory codes. For instance, the example of BP, Lin-Hi and Blumberg (2011) explains that it seems that there is a great need for the business community to become informed about the beneficial role of institutions and the idea of global governance. In business, the paradigm that still seems to be dominant is that “fewer rules are always better”. For instance, BP and virtually the entire oil industry was successfully lobbying for lower and less legal regulation of offshore drilling in the USA (see, e.g. Freudenburg and Gramling 2011). Against this old rule of game, it is important to emphasise that corporate long-term success does not depend on more or less rules, rather on good institutions (Lin-Hi and Blumberg 2011).

A study by O’Faircheallaigh and Kelly (2001) on mining companies’ policy and practices undertaken for the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission in 2001 found that six distinct categories were required to encompass the spectrum of behaviour observed. This ranged from active attempts by companies to deny aboriginal rights in relation to land at one extreme (either through individual action or through the activities of industry bodies such as Chambers of Mines), to actions that involved extensive departures from traditional corporate norms and behaviour at the other (O’Faircheallaigh and Kelly 2001).

Therefore, this can be suggested that improvements in CSR practices in last two decades have worked in favour and for aboriginal people in Australia. Dealing with mining companies is not the same as it was 20 years ago, when in fact many traditional owners had no opportunity to negotiate with resource developers. Indeed, in some cases, corporate policy and practice is considerably more accommodating of Aboriginal interests as a result.

In addition, global governance has been criticised as corporations go further than their host countries. The example of BP, Lin-Hi and Blumberg (2011) explain that it seems that there is a great need for the business community to become informed about the beneficial role of institutions and the idea of global governance. In business, the paradigm that still seems to be dominant is that “fewer rules are always better” (Lin-Hi and Blumberg 2011). For instance, BP and virtually the entire oil industry was successfully lobbying for lower and less legal regulation of offshore drilling in the USA (see, e.g. Freudenburg and Gramling 2011). Against this old rule of game, it is important to emphasise that corporate long-term success does not depend on more or less rules, rather on good institutions.

The emergence of voluntary codes of conduct

The growing recognition of good institutions and the impact of them on human security have led to the creation and adoption of voluntary codes of conduct. Stakeholders, becoming cognisant of the ability of multinational organisations to either positively or negatively impact the human security of individuals, have driven this move (Quek and Sarker 2011). Recent studies suggest that violations continue to occur but there are a number of important developments towards the full realisation of human security when institutions are operating in conflict states (Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights 2011). However, ensuring that their operations do not contravene fundamental human rights is not only good corporate citizenship, but will also help protect extractive industry from a range of adverse legal, political, social, economic and reputational risk.

International developments in regulation have seen a renewed emphasis on self-regulatory mechanisms. Of particular importance are voluntary codes of conduct administered by an industry body, rather than the government or an individual corporation (Gunningham et al. 1998). The adoption of voluntary codes of conduct in the Australian mining and extractive industries is in line with the international development of such mechanisms. Corporate social responsibilities encompass legal obligations including, of particular relevance in this case, the need to comply with cultural heritage legislation that applies federally and in all states and territories. CSR goes well beyond compliance with the law, with many companies now convinced that they must secure the social licence to operate and maintain a positive profile with the wider public in order to operate profitably in a secure environment (see, e.g. Handelsman 2002; Mirvis 2000).

In the mining and petroleum in particular, CSR standards, codes and accountability mechanisms that pertain to mining originate with individual companies, industry associations (e.g. the Mining Association of Canada or the International Council on Mining and Metals), governments (e.g. Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights), standard setting and certification bodies (e.g. International Organization for Standardization’s Guidelines for Social Responsibility 26000), non-governmental organisations (e.g. Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance), financial institutions (e.g. the Equator Principles and the International Finance Corporation’s Performance Standards), and with the United Nations (such as the Kimberley Process, the United Nations Norms on the responsibilities of transnational corporations and other business enterprises with regard to human rights (UN norm), and the United Nations Global Compact; Coumans 2010).

A plethora of standards and ‘guidance notes’ on all manner of CSR topics has been released by numerous global institutions, including the International Council on Mining and Metals’ Sustainable Development Principles (ICMM 2003), the International Finance Corporation’s (IFC) Performance Standards on Social and Environmental Sustainability (IFC 2006), and the World Resources Institute’s Guidebook on Engaging Communities in Extractive and Infrastructure Projects (WRI 2009). A particular case highlighting a more intense focus on implementation is the 3-year extension in 2008 by the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council of the mandate of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Business and Human Rights, who has engaged extensively with extractive industries, in order to ‘operationalize’ the Protect Respect Remedy framework that clarifies business responsibilities in relation to human rights, a key aspect of CSR in mining (O’Faircheallaigh and Ali 2007).

Mining companies are among those that pioneered the production of environmental reports. Noranda, a Canadian mining and metals company, released its first report in 1991 (Buhr 2007), and then reported annually. By 2002, eight out of the ten biggest global mining companies were publishing annual environmental reports as a stand-alone document, i.e., separated from general annual reports (Jenkins and Yakovleva 2006). Since the impact of mining activity in communities is quite visible, it is not a surprise that social performance was one of the most widely disclosed categories. Nevertheless, other topics should also be presented and discussed in depth, as controversial environmental impacts, such as the depletion of natural resources, economic impact on stakeholders and comparability in a wider context. Each year, stakeholders will expect more disclosure in all the three dimensions of sustainability, as well as transparent and mature discussions about relevant impacts (Perez and Sanchez 2009).

In the mid- to late 1990s, Rio Tinto increasingly became the target of international concern over its industrial relations policies, and over the impact of its mining operations on the environment and on human rights. In 1998, it came under fire from the International Federation of Chemical, Energy, Mine and General Worker’s Unions. In 2000, the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union coordinated an international shareholder campaign at Rio Tinto’s Annual General Meeting, seeking the appointment of an independent, non-executive director to the company’s board and the introduction of “a credible workplace code of labour practice”. Contemporaneously with, and perhaps because of, these developments, the company also moved towards the adoption of a comprehensive CSR strategy (Jones et al. 2007). Important aspects of this are as follows. A designated sub-committee of the general Board was given direct oversight and responsibility for the CSR strategy, and an annual report now details its CSR targets and results. Internationally, Rio Tinto became a signatory to the UN Global Compact, and endorsed the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the US/UK Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights.

For various reasons, BHP was also under reputational pressure. It had suffered a substantial public relations blow when its mining operation had resulted in significant damage to the local environment and community in a developing country (Hanson and Stuart 2001). With the merger came the prospect of further risk to BHP’s reputation through association with Billiton’s highly controversial human rights record in Africa. As part of this CSR policy, BHP has made a commitment to the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the UN Global Compact. It is listed on the Dow Jones Sustainability and the FTSE4Good Indexes (Jones et al. 2007).

The facilitated self-assessment process is garnering increasing attention within the minerals sector, with a small number of companies opting to supplement the traditional audit with a less conventional prelude. Rio Tinto, for example, outlines its requirements for self-managed assessments every 3 years as part of its Communities Standard (Rio Tinto 2010). It is clear that the decision of companies to develop community strategies does not stem from a moral choice; it is as a strategic response to social challenges that constantly shift the background of constraints in which the organisation must operate (Jenkins 2004). Further research may focus on whether community development programmes implemented by mining companies actually deliver socially responsible outcomes or whether they simply create mechanisms of dependency that can be used to control communities.

Stakeholder influence on regulatory mechanisms

In this modern era of prolific regulation, many businesspeople may well consider that any hazards and harms their corporation engenders will sooner or later be subject to public censure, and hence future regulation (Gunningham et al. 2002). This implies that not only do stakeholders have an important part to play in bringing to bear pressure on the government to impose command and control regulation, but also in influencing the level of voluntary compliance in firms.

Stakeholders can be defined as those groups who share a common interest in engaging with and influencing the political process in order to protect their economic interests, avoid negative externalities or maintain their political power (Fidrmuc and Noury 2003). Although precise stakeholder identification can be a difficult process (Phillips 2003), Mitchell et al. (1997) propose three factors that should be considered in order to determine the importance of the stakeholders’ claims. The first factor is the stakeholders’ power to influence decision making, whether through control over financial resources, or public opinion. The second factor is the legitimacy of the stakeholder’s relationship to the government. A stakeholder should have something ‘at risk’ from the proposed reforms. The third factor is the urgency of the stakeholders’ claim, which will occur when the claim is of a time-sensitive nature and when the claim is important to the stakeholder. In the mining industry, for example there are a number of stakeholders considered by mining companies. These include shareholders, internal stakeholders such as employees, funding agencies like banks and socially responsible investment, industry organisations, regulatory bodies, community groups, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the media.

The role that stakeholders can play in motivating voluntary compliance by firms stems from the idea of a social licence to operate, since organisations need community acceptance in order to continue to operate. The social licence to operate means that businesses must be responsive to pressure from the community and other stakeholders, particularly where there is a high impact on the community. For example, the pulp and paper mill industry studied by Gunningham et al. (2002) shows strong evidence of going beyond compliance in response to community and other stakeholder concerns in order to maintain its social licence to operate. Similarly, Nilsen (2010) shows how banks responded to the post-global financial crisis (GFC) public dissatisfaction with the financial services sector by implementing CSR programmes that went far beyond their legal obligations. Maintaining a social licence to operate is important because failure to respond to community and other stakeholder concerns runs the risk of expanding the command and control regulation on the business, since governments and regulators are required to be responsive to public concerns (Gunningham et al. 2002).

In the present case, the MCA’s Enduring Value Framework for mining and APPEA’s Principles of Conduct and Code and Environmental Practice were both adopted in response to growing pressures for the industries to be seen as more socially and environmentally responsible. It is widely accepted that focus on corporate reputation and credibility regarding social and environmental performance has been on the increase since the 1990s (Schiavi 2005). This has given rise to a number of pressures placed by stakeholders on the mining and oil and gas sectors (Sarker and Gotzmann 2009), driven by the increasing momentum of NGOs supporting social and environmental issues (Brereton 2002; Rondinelli and Berry 2000; Sarker and Burritt 2005a, b); the increasing use of electronic communications by stakeholders (Brereton 2002; Schiavi 2005); and a number of high profile environmental disasters fostering public mistrust of the mining and oil & gas industries (Brereton 2002; MMSD 2002). For example, Ok Tedi in PNG, and several oil spills: Exxon Valdez in Alaska in 1989; North Sea in 1988; and Kirki in Western Australia in 1991 (Elkington 1999; AMSA 2006) caused severe reputational damage to the mining and extractives industry, as well as the oil and gas sector, which gave both industries a serious reputational image problem (Patten 1992; Elkington 1999).

In Australia, for instance, aborigines refused to accept the marginalisation imposed by the mining industry and fought hard to control mining. In some cases, they were able to influence development decisions or insist on a share of benefits, either formally through the rare opportunities provided by legislation such as the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Altman 1983), or informally by drawing developers into de facto arrangements for benefit sharing ‘on the ground’ (O’Faircheallaigh 2006). On the bright side, mineral development in Australia is increasingly controlled by a small number of large companies that operate across Australia’s mineral-producing regions. The subsidiaries of these companies share information and develop and implement policies and strategies across numerous projects and operations. Recognition of native title, legislative changes and emphasis on ‘corporate social responsibility’ policies create opportunities for aboriginal landowners to influence and benefit from mineral development on their traditional land (O’Faircheallaigh 2006). Today, the developments of ‘corporate social responsibility’ policies have led major mining companies to negotiate with Aboriginal traditional owners even in the absence of a legal requirement to do so (O’Faircheallaigh and Kelly 2001). A broad policy consensus in Australia in which this has led to mineral development and should proceed with the agreement of, rather than over the opposition of, aboriginal traditional owners (ATSISJC 2004, 103–4; Beattie 2003).

Maintaining organisational legitimacy: does it matter to the Australian mineral and petroleum industries?

Social expectations are also different in different world regions, as the comparison of Australian and European surveys has shown. A comparison of the results of Australian and European surveys indicate that Australians are most interested in quality of products, management and financial performance (Van der Molen 2005), whereas European studies show that in most countries employees, environment and service are the most important themes of CSR reporting (Ind 1997; Golob and Bartlett 2007).

A corporation must maintain its social licence to operate in order to be perceived as legitimate. The growing instances of corporate wrong-doing, legal action and social attitudes suggest that the legitimacy of the body corporate is under threat (Rayman-Bacchus 2006), and accordingly the maintenance of legitimacy has become one of the most critical issues for corporations in the twenty first century (Castelló and Lozano 2011). Legitimacy refers to the ethical and discretionary behaviour of organisations, and suggests that the actions that organisation take to achieve their objectives and the outcomes of their actions are accepted by the society they live in (Puncheva 2008). There are two possible bases for organisational legitimacy: the institutional approach and the strategic approach (Castelló and Lozano 2011). The institutional approach looks at how organisations build support for their legitimacy by maintaining normative and widely supported organisational characteristics to signal normativity, credibility and legitimacy to outside audiences (Fombrun and Shanley 1990). Compliance with community expectations is thus dependant on providing certain accounts of social and environmental outcomes. This is a continuous process of adaptation to external expectations (Castelló and Lozano 2011). The strategic approach argues that legitimacy is an operational resource which can be managed and directly influenced by the corporation in order to gain societal support (Castelló and Lozano 2011). Legitimacy is often considered as being based in the meanings, structures and institutions that facilitate social integration (Reus-Smit 2007). It is important to note that the immediate assumption behind both these concepts of legitimacy is that corporations’ social environments consist of a coherent set of moral norms and rules: “broader community values” (Castelló and Lozano 2011). Castelló and Lozano (2011) argue that a third form of legitimacy is beginning to appear: moral legitimacy, which is needed in order to comply with new sustainability expectations among consumers, governments and shareholders.

Legitimacy is conferred or withdrawn by an organisation’s activities being judged against a set of accepted standards. It is because of this that voluntary codes of conduct developed by industry bodies have proliferated in recent times (Patel et al. 2005). However, it is important that these industry bodies also maintain legitimacy in order to promote public confidence in the voluntary regulatory system. Failure to do so can alienate citizens from self-regulatory institutions (Bratspies 2009) and gives rise to the possibility of command and control regulation being imposed by governments (Gunningham et al. 1998). To be successful, a self-regulatory mechanism must be capable of improving the industry’s poor public image, restoring public faith in the industry’s integrity and taking the heat out of demands for stricter government regulation (Gunningham 1998). It is considered to be crucial to have some common norms and standards, so that firms are not only focusing on their own ethics, but rather working together on sector-specific challenges (Nilsen 2010). Trust in the impartiality of institutional procedures can contribute to increased trust in the CSR practises of an organisation (Rayman-Bacchus 2006). When CSR practises become the norm in the industry, firms have strong incentives to gain legitimacy by engaging in those practices. Benefits not only include a better reputation and legitimacy and better market access, but also the possibility to gain crucial knowledge and inspiration from peers. The co-operation in an industry may lead to firms telling the same story, meaning that responsible moves will be perceived as business as usual (Nilsen 2010). In this situation, firms are likely to do the minimum possible to achieve compliance (Hickman and Hill 2010) and hence seen as less sincere (Nilsen 2010).

The mining and extractives industry and the oil and gas sector are similar in that they are widely recognised as being severely disruptive on the local environment and community (Hajkowicz et al. 2011). This often generates natural resource conflicts which are typically “severe and debilitating, resulting in violence, resource degradation, the undermining of livelihoods, and the uprooting of communities” and, if not addressed, “can threaten to unravel the very fabric of society” (Castro and Nielsen 2001). The gradual introduction of local-level community engagement and grievance mechanisms as an organisational strategy has occurred against the backdrop of continual conflict with the community over natural resources (Kemp et al. 2011). Mining companies cannot ignore community expectations in the current climate: it is for this reason they design community relations programmes so that they are seen as a good neighbour (Patel et al. 2005) to maximise the benefits and minimise (or mitigate) the harms to the public (Ivanova et al. 2007). This helps mining companies maintain legitimacy and conform to social expectations about how the mining operation should be conducted. Failure to do so may give rise to a legitimacy crisis (Castelló and Lozano 2011) where the company no longer has a social licence to operate.

Since legitimacy is the interaction between organisational strategy and stakeholder expectations, legitimacy management is best viewed as a dialogic process, rather than a monologic organisational activity (Massey 2011). For example, Kemp et al. (2010) analyse the dialogic process of a mining company developing a change agenda for gender and community relations. The purpose of dialogue between an organisation and its public is motivated by a constant need to legitimise its actions (Patel et al. 2005). Rayman-Bacchus (2006) argues that corporations cannot legitimise themselves, since they are accountable to stakeholders and institutions that set performance criteria beyond corporate control. In order to maintain functional relationships with stakeholders, organisations must continually adjust their actions by reference to stakeholders’ expectations and needs.

The concepts of legitimacy defined above show that, for an organisation to be considered legitimate, its identity, interests or practices must resonate with values considered normative by other actors, or stakeholders (Reus-Smit 2007). Unlike reputation, legitimacy emphasises the social acceptance gained from adherence to social norms and expectations (Nilsen 2010). Firms are thus perceived to be legitimate when their goals, methods of operation and outcomes are congruent with the expectations of those who confer legitimacy (Lindblom 1994). Given the above stakeholder theory discussion, developing and maintaining legitimacy requires communicating with stakeholders. Organisational legitimacy has a critical role in building and maintaining the expectations of stakeholders, and hence is argued to be a foundational concept of public relations (Patel et al. 2005). To this end, a range of literature focuses on different stakeholder communication strategies an organisation can use during a crisis to influence the public’s perception of the organisation and restore its damaged image among stakeholders(Stephens et al. 2005). The falling level of trust in business illustrates the need to introduce better CSR practices and introduce repairing strategies aiming to boost reputation and legitimacy (Nilsen 2010).

A legitimacy crisis occurs when an organisation’s failure to cultivate sufficient legitimacy has reached a critical turning point (Reus-Smit 2007). An organisational crisis can be further defined as: threatening high-priority values of the organisation; presenting a restricted amount of time in which a response can be made; being unexpected; and a social construction, rather than an objective measure (Nilsen 2010). The definition of Coombs (2007) of a crisis is useful: “A crisis is the perception of an unpredictable event that threatens important expectancies of stakeholders and can seriously impact an organisations’ performance and generate negative outcomes.” Examples of legitimacy crises in the corporate world are varied and diverse. Nilsen (2010) examines the example of the legitimacy crisis experienced by the banking sector after the global financial crisis. He shows how banks, experiencing negative media attention, slumping trust and weakened legitimacy in light of the global financial crisis and irresponsible behaviour created a need for banks to work on strategic legitimacy in order to regain trust and enhance reputation. According to Gunningham (1998) large chemical corporations usually find it difficult to improve their corporate image without changing the reality through improved environmental performance. The continued and serious decline of the public image of the chemical industry therefore due to several serious accidents, combined with broader concerns about the environmental impacts of chemical production, meant that major companies could not advertise their way out of their legitimacy crisis.

Gunningham (1998) further writes that, absent a change in public attitudes, the long term survival of the chemical industry was under threat. This legitimacy crisis of the chemical sector led to the establishment of responsible care. As outlined by Gunningham (1998), responsible care is a self-regulatory initiative under which a number of codes of practice were established and a commitment to community consultation was made. The responsible care scheme also commits to genuine improvement that goes beyond compliance with existing environmental protection legislation. Gunningham (1998) writes that an industry wide, rather than an individual undertaking was necessary to give the industry as a whole the legitimacy to continue to exist.

The mining and extractives industry, and the oil and gas sector, are other examples of industries that have experienced legitimacy crises in recent decades. As discussed above, both industries experienced severe reputational damage because of high-profile major environmental incidents and growing environmental consciousness. This growing environmental awareness resulted in increased environmental conflicts, litigation, activism by NGOs and consumers, shareholder activism and ethical investment, and greater transparency into corporate activities provided by the media (Utting 2005). These pressures not only caused mining companies significant reputational damage and a resulting legitimacy crisis. This situation led to increased environmental protection regulation by the government, but also an uptake of CSR initiatives by most corporations and the introduction of voluntary codes of conduct by both the minerals and petroleum sectors (Utting 2005; Whellams 2007). These voluntary initiatives occurred to restore the legitimacy of the industry, and avoid more stringent command and control regulation.

This is consistent with the theory, which states that an organisation can repair its legitimacy by taking the following steps. First, the organisation is required to recalibrate the relationship between its social identity, purposes, practices, and the prevailing social norms. Second, the organisation must realign its realm of action with its social constituency of legitimation. This process of legitimation will necessarily involve interpretative argument over the nature and meaning of applicable social norms (Reus-Smit 2007). There are a number of different strategies that can serve to re-establish legitimacy following a crisis (Suchman 1995). These strategies aim to change society’s perceptions and expectations towards the firm, and fall under two main headings: normalising the account of the crisis, or restructuring (Nilsen 2010). Normalising the account of the crisis includes denial, excuses, justification. Restructuring includes disassociating the firm from bad influences, or creating monitors and watchdogs which allow the firm to invite state regulation, ombudsmen or grievance procedures. Meyer and Rowan (1977) argue a third strategy is for firms to adopt highly visible practices consistent with social expectations. In the absence of pressure from formal institutions, firms are more likely to behave irresponsibly (Nilsen 2010). Nilsen (2010) demonstrates how banks responded to the post-GFC scrutiny from public opinion and the state by applying more elements of formal CSR programmes in order to demonstrate their intention for future good behaviours. These include providing financial literacy courses to youth, abolishing profit-based bonus payments and emphasising product responsibility, launching a ‘Better Bank’ campaign to inform the public of their reforms, and engaging with social media for suggestions on how to behave in the future. These strategies are likely to raise moral legitimacy, because promoting social welfare will be perceived as the right thing to do. Similarly, Gunningham (1998) shows how the chemical sector responded to their legitimacy crisis by establishing the Responsible Care initiative. The main motivators were improved corporate image and improved community relations, as well as competitive advantage and increased profitability. The Responsible Care mechanism enabled the development of an industrial morality capable of challenging conventional industry practices by establishing a set of norms which generated a sense of obligation (Gunningham 1998).

In this situation of a legitimacy crisis, where a corporation’s reputation is damaged and public dissatisfaction with the company is high, firms will often go beyond compliance in response to pressures from their stakeholders. This is done in order to repair its tarnished reputation and regain its social licence to operate and legitimacy in the eyes of the community. Actions that may be taken to restore legitimacy and a social licence to operate may include going above and beyond existing environmental protection standards (Gunningham et al. 2002), implementing new CSR programmes (Nilsen 2010) or establishing new voluntary codes of conduct (Gunningham 1998).

The establishment of the self-regulatory initiatives in the Australian mining and extractive industry should thus be considered in the context of greater social and environmental scrutiny of mining and extractive industries. Since the actions of a single company reflected badly on the industry as a whole, individual CSR initiatives were no longer enough: what was needed was an industry-wide initiative that restored legitimacy to a whole industry (Gunningham et al 1998). The voluntary codes of conduct introduced by the mining and extractives industry, and the oil and gas sector, reflect the industries’ need to engage in “beyond compliance” CSR activities in order to regain their legitimacy, or risk the imposition of costly command and control regulation as a result of public pressure on the state (Gunningham et al. 2002; Nilsen 2010). The MCA’s Enduring Value Framework and the APPEA’s Principles of Conduct and Code and Environmental Practice are two examples of this: both were introduced in response to increased public scrutiny on their industry (Sarker and Gotzmann 2009). This relates to the idea of corporate accountability, which states that corporations have to account to their stakeholders, and hence their rights and freedoms should be balanced by obligations (Utting 2005), although the motivation for adoption of voluntary codes of conduct is usually more related to the improvement of corporate image, rather than performance (Sarker and Gotzmann 2009). This is shown by the fact that voluntary codes of conduct are usually pushed through by larger companies that are more reputation sensitive, rather than smaller companies (Brereton 2002). Sinclair (1997) argues that because these codes of conduct were established in an attempt to avoid more formal government regulation, they cannot be characterised as truly voluntary.

It is thus important to consider voluntary codes of conduct in the context of the much broader regulatory and operational environment experienced by the firm. In particular, considerations of legitimacy and maintaining a social licence to operate may motivate the adoption of voluntary codes of conduct in the first place, as well as affecting the level of compliance with these codes that a firm undertakes. The experience of the Australian mineral and petroleum industries shows that companies are responsive to the expectations of their stakeholders. Companies that have breached their social licence to operate by poor social and environmental conduct must regain their legitimacy by beyond compliance CSR actions. This often includes the introduction of voluntary codes of conduct or other self-regulatory initiatives that are not only designed to avoid more formal command and control regulation, but also to restore the legitimacy of the industry in the eyes of its stakeholders. The introduction of the MCA’s Enduring Value Framework for mining, and APPEA’s Principles of Conduct and Code and Environmental Practice for petroleum were both directed at regaining lost legitimacy due to poor CSR practices. The introduction of these voluntary codes thus signalled to stakeholders that the industry’s CSR practices would improve, contributing to renewed trust in the industry and regaining their social licence to operate.

Conclusion

As Jones et al. (2007) have noted, companies may be particularly responsive to criticism when they operate in industries which expose them to a high degree of “reputational risk”, or where their internationalisation brings with it greater exposure. But does the existence or co-existence of these factors, and the adoption of a CSR strategy in the same context, necessarily translate to a reformulation of company policy in keeping with the adopted CSR standards? The outcome of our studies seems to suggest that whilst companies might be sensitive to how their activities are socially received, they may nevertheless continue with even highly controversial policies if there are perceived sound business reasons for doing so. While the focus of this research is the mining and petroleum industry, the methods proposed have applicability in other industries that are also seeking to move from ideal notions of CSR to a more meaningful engagement with the challenges associated with linking global norms with local expectations.

Voluntary codes of conduct are an important self-regulatory mechanism by which the Australian minerals and petroleum industries have responded to concerns about their social and environmental conduct that engendered a legitimacy crisis. The introduction of voluntary codes of conduct is a signal by the industry that their CSR practices have improved. Accordingly, both the MCA’s Enduring Value Framework for mining, and the APPEA’s Principles of Conduct and Code and Environmental Practice for petroleum were introduced in response to stakeholder concerns in an effort to maintain their social licence to operate. However, rather than being purely voluntary, these codes of conduct have enabled both industries to avoid more formal command and control regulation. Voluntary codes of conduct are an important part of the regulatory landscape, and are part of this new era of regulatory pluralism. Given that the current self-regulatory initiatives in the Australian minerals and petroleum industries were developed in response to stakeholder pressures, it is reasonable to presume that self-regulatory initiatives will continue to be responsive to the changing views of stakeholder sin the future, as failure to do so could engender another legitimacy crisis.

References

Albareda, L. (2008). Corporate responsibility, governance and accountability: from self-regulation to co-regulation. Corporate Governance, 8(4), 430–439.

Altman, J. (1983). Aborigines and mining royalties in the Northern territory. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

ATSISJC (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner). (2004). Native title report 2003. Sydney: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) (2006). Major oil spills in Australia. Available at: http://www.amsa.gov.au/Marine_Environment_Protection/Major_Oil_Spills_in_Australia. Accessed 11 July 2008.

Ayres, I., & Braithwaite, J. (1992). Responsive regulation: transcending the deregulation debate. New York: Oxford University Press.

Barkay, T. (2009). Regulation and voluntarism: a case study of governance in the mining sector. Regulation and Governance, 3(4), 360–375.

Baron, D. (2010). Morally motivated self-regulation. American Economic Review, 100(4), 1299–1329.

Beattie, P. (2003). New director to practice “Practical reconciliation”. Media release, Brisbane. 15 September 2003.

Braithwaite, J. (1993). Responsive business regulatory institutions. In C. Cody & C. Sampford (Eds.), Business, ethics and law. Sydney: Federation Press.

Braithwaite, V. (2006). Ten things you wanted to know about regulation but were too afraid to ask. Regulatory Institutions Network Occasional Paper 10. Australian National University.

Bratspies, R. (2009). Regulatory trust. Arizona Law Review, 51, 575–631.

Brereton, D. (2002). The role of self-regulation in improving corporate social performance: the case of the mining industry. Australian Institute of Criminology Conference: Current issues in regulation: enforcement and compliance. Melbourne.

Buhr, N. (2007). Histories of and rationales for sustainability reporting. In J. Unerman, J. Bebbington, & B. O’Dwyer (Eds.), Sustainability accounting and accountability (pp. 57–69). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Castelló, I., & Lozano, J. (2011). Searching for new forms of legitimacy through corporate responsibility rhetoric. Journal of Business Ethics, 100, 11–29.

Castro, A., & Nielsen, E. (2001). Indigenous people and co-management: implications for conflict management. Environmental Science and Policy, 4, 229–239.

Coombs, W. (2007). Protecting organisation reputation during a crisis: the development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 163–176.

Coumans, C. (2010). Alternative accountability mechanisms and mining: the problems of effective impunity, human rights, and agency. Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 30(1–2), 27–48.

Elkington, J. (1999). The triple bottom line: implications for the oil industry. Oil & Gas Journal, 97(50), 139–141.

Fallon, E. (2009). Voluntarism versus regulation: lessons from public disclosure of environmental performance information in Norwegian companies. Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change, 5(4), 472–489.

Fidrmuc, J., Noury, A. (2003). Interest groups, stakeholders and the distribution of benefits and costs of reform. Paper presented to the GDN Global Research Project Understanding Reform.

Fitzpatrick, P., Fonseca, A., & McAllister, M. L. (2011). From the Whitehorse mining initiative towards sustainable mining: lessons learned. Journal of Cleaner Production, 19(4), 3763–3784.

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name: reputation building and corporate strategy’. Academy of Management Journal, 2, 233–358.

Freudenburg, W. R., & Gramling, R. (2011). Blowout in the Gulf. The BP oil spill disaster and the future of energy in America. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Furger, F. (1997). Accountability and systems of self-governance: the case of the maritime industry. Law & Policy, 19(4), 445–476.

Golob, U., & Bartlett, J. L. (2007). Communication about corporate social responsibility: a comparative study of CSR reporting in Australia and Slovenia. Public Relations Review, 33, 1–9.

Gunningham, N. (1998). The chemical industry. In: Smart regulation: designing environmental policy. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gunningham, N., Grabosky, P., & Sinclair, D. (1998). Smart regulation: designing environmental policy. Oxford: Clarendon.

Gunningham, N., Kagan, R. & Thornton, D. (2002). Social licence and environment protection: why businesses go beyond compliance. Centre for the study of law and society jurisprudence and social policy program. Berkeley: University of California

Gunninghman, N., & Sinclair, D. (1998). Instruments for environmental protection. In: Smart regulation: designing environmental policy. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hajkowicz, S., Heyenga, S., & Moffat, K. (2011). The relationship between mining and socio-economic well-being in Australia’s regions. Resources Policy, 36, 30–38.

Handelsman, S. D. (2002). Human rights in the minerals industry. London: Mining Minerals and Sustainable Development and the International Institute for Environment and Development.

Hanson, D., & Stuart, H. (2001). Failing the reputation test: the case of BHP Billiton, the big Australian. Corporate Reputation Review, 4, 128–143.

Hickman, K., & Hill, C. (2010). Concepts, categories and compliance in the regulatory state. Minnesota Law Review, 94, 1151–1201.

Ind, N. (1997). The corporate brand. Oxford: Macmillan.

International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) (2003). ICMM sustainable development framework: 10 principles. Available from: http://www.icmm.com/our-work/sustainable-development-framework/10-principles. Accessed 15 August 2012.

International Finance Corporation (IFC) (2006). International finance corporation’s performance standards on social & environmental sustainability. Available from: http://www.ifc.org/ifcext/sustainability.nsf/AttachmentsByTitle/pol_PerformanceStandards2006_full/$FILE/IFCflPerformanceflStandards.pdf.

Ivanova, G., Rolfe, J., Lockie, S., & Timmer, V. (2007). Assessing social and environmental impacts associated with changes in the coal mining industry in the Bowen Basin, Queensland, Australia. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 6(2), 211–228.

Jenkins, H. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and the mining industry: conflicts and constructs. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 11, 23–34.

Jenkins, H., & Yakovleva, N. (2006). Corporate social responsibility in the mining industry: exploring trends in social and environmental disclosure. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14, 271–284.

Jones, M., Marshall, S., & Mitchell, R. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and the management of labour in two Australian mining industry companies. Corporate Governance, 15(1), 57–67.

Kemp, D., Bond, C., Franks, D., & Cote, C. (2010). Mining, water, and human rights: making the connection. Journal of Cleaner Production, 18, 1553–1562.

Kemp, D., Owen, J. R., Gotzmann, N., & Bond, C. J. (2011). Just relations and company-community conflict in mining. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(1), 93–109.

Kemp, D., Owen, J. R., & van de Graaff, S. (2012). Corporate social responsibility, mining and “audit culture”. Journal of Cleaner Production, 24, 1–10.

Lindblom, C. (1994). The implications of organisational legitimacy for corporate social performance and disclosure. Paper presented at the Critical Perspectives on Accounting Conference, New York

Lin-Hi, N., & Blumberg, I. (2011). The relationship between corporate governance, global governance, and sustainable profit: lessons learned from BP. Corporate Governance, 11(5), 571–584.

Massey, J. (2011). Managing organizational legitimacy: communication strategies for organizations in crisis. Journal of Business Communication, 38, 153–182.

May, P. (2003). Performance-based regulation and regulatory regimes: the saga of leaky buildings. Law and Policy, 25(4), 381–401.

Meyer, J., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalised organisations: formal structures as myth and ceremony. The American Journal of Sociology, 83, 340–363.

Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development (MMSD). (2002). Breaking new ground: the report of the MMSD project. London: Earthscan Publications.

Mirvis, P. H. (2000). Transformation at shell: commerce and citizenship. Business and Society Review, 105(1), 63–84.

Mitchell, R., Agle, B., & Wood, D. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22, 853–886.

Newman, A., & Bach, D. (2004). Self-regulatory trajectories in the shadow of public power: resolving digital dilemmas in Europe and the United States. Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration and Institutions, 17(3), 387–413.

Nilsen, H. (2010). CSR in banking—the pursuit toward repairing legitimacy and reputation: a case study of Den Norske Bank and Danske Bank. Masters Thesis, Copenhagen Business School, Submitted August 9.

O’Faircheallaigh, C., & Ali, S. (2007). Extractive industries, environmental performance and corporate social responsibility. Greener Management International. The Journal of Corporate Environmental Strategy and Practice, 52, 5–16.

O’Faircheallaigh, C. (2006). Aborigines, mining companies and the state in contemporary Australia: a new political economy or ‘business as usual’? Australian Journal of Political Science, 41(1), 1–22.

O’Faircheallaigh, C., & Kelly, R. (2001). Corporate social responsibility, native title and agreement making: report to the human rights and equal opportunity commission. Brisbane: Griffith University.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (1994). Meeting on alternatives to traditional regulation. Paris.

Parker, C. (2008). The pluralisation of regulation. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 9, 349–369.

Patel, A., Xavier, R., & Broom, G. (2005). Toward a model of organisational legitimacy in public relations theory and practice. In Proceedings of the International Communication Association Conference (pp. 1–22). New York.

Patten, D. M. (1992). Intra-industry environmental disclosures in response to the Alaskan oil spill: a note on legitimacy theory. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(5), 471–475.

Pennington, L., & More, E. (2010). Sustainability reporting: rhetoric versus reality? Employment Relations Record, 10(1), 24–39.

Perez, F., & Sanchez, L. E. (2009). Assessing the evolution of sustainability reporting in the mining sector. Environmental Management, 43, 949–961.

Phillips, R. (2003). Stakeholder legitimacy. Business Ethics Quarterly., 13(1), 25–41.

Posner, R. (2007). Evolution and development of self-regulation. New York: American Museum of Natural History.

Puncheva, P. (2008). The role of corporate reputation in the stakeholder decision making process. Business Society, 47, 272–290.

Puplampu, B., & Dashwood, H. (2011). Organisational antecedents of a mining firm’s efforts to reinvent its CSR: the case of Golden Star Resources in Ghana. Business and Society Review, 116(4), 467–507.

Quek, M., & Sarker, T. (2011). Transnational corporations in the extractive industries operating in conflict States. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 44, Greenleaf Publishing.

Rayman-Bacchus, L. (2006). Reflecting on corporate legitimacy. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 17, 323–335.

Reus-Smit, C. (2007). International crises of legitimacy. International Politics, 44, 157–174.

Rio Tinto (2010). Communities standard. Available from: http://www.riotinto.com/documents/Communities_standard.pdf. Accessed 19 September 2011.

Rondinelli, D. A., & Berry, M. A. (2000). Environmental citizenship in multinational corporations: social responsibility and sustainable development. European Management Journal, 18(1), 70–84.

Sarker, T. (2005). Towards a sustainable business strategy for environmentally sensitive industries: the case of the Australian petroleum industry. In Proceedings of the 6th Asia-Pacific Rim Universities Doctoral Students Conference, University of Oregon, 7–12 August, USA

Sarker, T. (2008). An empirical examination of factors influencing managers’ environmental investment decisions in the Australian offshore petroleum industry. PhD Thesis, Australian National University.

Sarker, T. K., & Burritt, R. L. (2005a). Does self-regulation improve corporate ecological-efficiency? An empirical investigation into the Australian investigation into the Australian Petroleum Industry From 1996 to 2002. APPEA Journal, 511–522.

Sarker, T. K., & Burritt, R. L. (2005b). Towards a sustainable business strategy for environmentally sensitive industries: the case of the offshore oil and gas industry in Australia. 6th APRU Doctoral Students Conference (pp. 1–13). USA: University of Oregon.

Sarker, T., & Gotzmann, N. (2009). A comparative analysis of voluntary codes of conduct in the Australian mineral and petroleum industries. Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining. University of Queensland.

Schiavi, P. (2005). Regulating the social and environmental performance of the Australian minerals industry: a sociological analysis of emerging forms of governance. Regulatory Institutions Network Conference. ANU, Canberra

Sinclair, D. (1997). Self-regulation versus command and control? Beyond false dichotomies. Journal of Law and Policy, 19(4), 529–559.

Steinzor, R. (1998). Reinventing command and control regulation: the dangerous journey from command to self-control. Harvard Environmental Law Review, 22, 103–203.

Stephens, K., Malone, P., & Bailey, C. (2005). Communicating with stakeholders during a crisis: evaluating message strategies. Journal of Business Communication, 42(4), 390–419.

Stewart, R. (1995). United States environmental regulation: a failing paradigm. Journal of Law and Commerce, 15, 585–596.

Suchman, M. (1995). Managing legitimacy: strategic and institutional responses. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610.

Utting, P. (2005). Corporate responsibility and the movement of business. Development in Practice, 15(3–4), 375–389.

Van der Molen, A. (2005). What really matters: what opinion leaders think and what others think of us. In Presentation at PRIA Conference 2005.

Van Oosterhout, J., & Heugens, Pursey, P.M.A.R. (2006). Much Ado about nothing: a conceptual critique of CSR. ERIM Report Series Reference No. ERS-2006-040-ORG. Available from http://ssrn.com/abstract=924505. Accessed 21 Dec 2012.

Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights (2011). The principles: introduction. www.voluntaryprinciples.org/principles/introduction. Accessed 13 Aug 2012.

Whellams, M. (2007). The role of CSR in development: a case study involving the mining industry in South America. Master’s Thesis, Saint Mary’s University, Nova Scotia.

Whitmore, A. (2006). The emperors’ new clothes: sustainable mining? Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(3–4), 309–314.

World Resources Institute (WRI) (2009). Breaking ground: engaging communities in extractive and infrastructure projects. Available from: http://www.wri.org/publication/breaking-ground-engaging-communities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sarker, T.K. Voluntary codes of conduct and their implementation in the Australian mining and petroleum industries: is there a business case for CSR?. Asian J Bus Ethics 2, 205–224 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-012-0027-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-012-0027-3