Abstract

Along with China’s stunning economic growth, marketing has become a multi-billion dollar business, afflicted by a plethora of marketing scandals. However, little attention has been paid, until now, to a more systematic approach to marketing ethics in China. This essay attempts to provide a broad and timely, but far from complete, view on marketing issues in China. It uses four ethical guidelines which capture the fundamental features particularly relevant to marketing activities: practicing honest communication; enhancing human capabilities; fostering creative intercultural diversity; and promoting sustainable growth and eco-efficiency. These guidelines are then elucidated with 12 positive and negative cases of Chinese and non-Chinese companies. By combining guidelines with case studies, it is hoped that ethical challenges for marketing in China will be discerned in a more systematic and comprehensible fashion. The article concludes by indicating several perspectives for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ten years ago, on November 10, 2001, China was formally approved to enter the World Trade Organization (WTO). Since then, China has experienced a rapid economic rise. “This growth surprised the world, and it has even gone beyond Chinese expectations,” said Long Yongtu, the former minister of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation and one of the four heads of China’s delegation to the WTO negotiations. China’s GDP surged to 40 trillion yuan (US $6.29 trillion) in 2010, from 11 trillion yuan in 2001, making the nation the world’s second largest economy (see China Watch 2011, p. 2).

Along with this stunning growth, marketing has become a multi-billion (dollar) business.Footnote 1 It has brought about far-reaching changes in how customers and citizens in China perceive business activities and evaluate the reputation of enterprises. While the levels of information and access concerning products and services have significantly improved and marketing has become aesthetically better—compared with the beginnings of the economic reform and opening up in the 1980s—one should also mention that the last ten years have brought about a plethora of marketing scandals increasingly reported in the media in China and abroad.

Scandals have broken in a wide range of industries and among Chinese and non-Chinese companies alike. A few concrete examples may illustrate the pervasive lack of ethics in marketing: the melamine-tainted milk scandal (Santoro 2009, p. 49 ff.); supplier fraud at Alibaba (sources of Alibaba case); Baidu selling links to unlicensed medical sites with unproven claims for their products (sources of Baidu case); Baxter International selling the blood thinner heparin with contaminated ingredients produced in China (Santoro 2009, p. 47 ff.); Carrefour using misleading price tags and fake discounts (sources of Carrefour case); Walmart labeling ordinary pork as organic (sources of Walmart case); Groupon China in pledge over fake (Financial Times 11/8/2011, p. 17); Da Vinci claiming fake production location (in Italy) and selling counterfeit products (sources of Da Vinci case); double standards in marketing practices of multinationals in China (Nestle, HP, and Toyota; Wu et al. 2011); OTIS running unsafe escalators (sources of OTIS case); Chinese fraud stocks listed in the US capital market (Liu et al. 2011); Foxconn’s exploitative working conditions with ten young workers killing themselves (sources of Foxconn/Apple case); Apple’s supplier responsibility with Foxconn and Unitec (sources of Apple case); the Jilin chemical plant explosions and subsequent toxic pollution of the Songhua river (sources of Jilin case); and Conoco Philips’s oil spills in the Bohai Bay (sources of ConocoPhillips case). Further examples from the 1990s can be found in Ryan et al. (2000, pp. 73–84, 179–188) and Xu Dajian (in Lu and Enderle 2006, pp. 144–150).

Despite this multitude of scandals, little attention has been paid, until now, to a more systematic approach to marketing ethics in China. The most recent survey on business ethics in research, teaching, and training in China shows that this topic area is addressed quite rarely (see Zhou et al. 2010). Marketing ethics is not mentioned at all in teaching and ranks in the 16th position (out of 17 positions) as topics in training. As for a theme in research, it ranks in the 23rd position (out of 48 positions) before finance (33rd) and accounting (37th). And even if other topic areas related to marketing ethics (such as CSR and business ethics) are included, the study and training in marketing ethics are still in their infancy.

Therefore, the time appears to have come to more clearly perceive a need for marketing ethics in China and to deepen its understanding. This essay attempts to discern several ethical challenges for marketing in China. It uses a framework for international marketing ethics developed elsewhere (Enderle 1998) and applies it to a selection of the cases mentioned above. Although the framework was designed for international marketing, it also might be relevant for the Chinese context, given China’s close connections with international business through the WTO. The emphasis of the article is placed on discerning rather than meeting those challenges, on the assumption that identifying and understanding the problems are indispensable first steps before these problems can be solved. Of course, problem solving remains the ultimate purpose of marketing ethics.

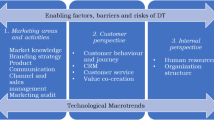

The framework consists of four ethical guidelines which capture the fundamental features particularly relevant to marketing activities. Each highlights a specific dimension with a certain value, which is interconnected with the other dimensions: communication, human development, cultural and religious embedment, and the natural environment. We do not claim that there exist no other important dimensions or that we could dispose of the key concepts of ethics such as “responsibility,” “justice,” “rights,” and “avoiding harm.” Rather, these concepts are, in one way or another, included in the guidelines and would need explicit consideration in other studies. They would also draw on the growing literature of marketing ethics in general and business ethics in China in particular.Footnote 2

The four guidelines are:

-

1.

Practicing honest communication;

-

2.

Enhancing human capabilities;

-

3.

Fostering creative intercultural diversity; and

-

4.

Promoting sustainable growth and eco-efficiency.

In the following, each guideline is briefly characterized and subsequently applied to a few cases. The article concludes by indicating a few research perspectives.

Practicing honest communication

Communication is the lifeblood of marketing. It flows through all types of activities and affects sellers and buyers alike. Communication is a two-way process in which each side collects, transforms, and provides information. Thus, it comes as no surprise that communication is subject to all kinds of uses and misuses. Some people argue that communication in itself be “value free” and only the use of it should be considered an “ethical issue.” While not denying the instrumental value of communication, the very use of communication presupposes some “intrinsic value.” Otherwise, communication cannot take place. Simply speaking, a liar can only lie if his statement pretends to be true in itself.

Sissela Bok, who has written extensively on lying and deceiving, states, “the potential for deceit is present in all communication between human beings. The intentional effort to mislead people—whether labeled deceit, fraud, duplicity, or lying—constitutes the simplest and most tempting way of making people act against their will. In turn, it gives rise to the most common reason of distrust.” (Bok 1992, p. 242)

So the question arises how to define “honest communication.” Three points of clarification are suggested. First, we may recall that communication can involve multiple errors such as acoustical and visual misrepresentations, linguistic ambiguities, errors in translation, and intercultural barriers. In all these cases, communication is ethically questionable only if it is intended to mislead (this, however, does not nullify the ethical requirement to reduce these errors as much as possible).

It is only when human beings purposely distort, withhold, or otherwise manipulate information reaching others so as to mislead them that we speak of deceit or intentional deception. Intentional deception may be nonverbal in form, as when messages are conveyed by gestures or false visual clues, or verbal. When a speaker makes a statement in the belief that it is false and with intention to mislead the listener, we speak of lies. (Bok 1992, p. 242)

Hence, a false statement is not necessarily a falsehood or a lie.

Second, further qualification is needed about making, or abstaining from, statements. Many intentionally false statements, like jokes, rhetorical flourishes, or works of fiction, are not intended to mislead listeners and, therefore, are not deceitful. On the other hand, true statements can be meant to deceive when one deliberately conveys excessive, confusing, correct, but nonetheless partial, information, knowing that the listener will not be able to interpret it correctly. Also, silence can be deceitful if it conveys a message intended to mislead.

Third, according to Bok, the term “honesty” is a broad one and

characterizes a person of integrity and trustworthiness (together) who avoids, not only lies, nor only intentional deception, but also theft and other forms of betrayal. Conversely, “dishonesty” refers to the disposition to lie, deceive, steal, cheat, and defraud more generally than “deceitfulness”, which concerns primarily the disposition to deceive. (Bok 1992, p. 243)

By qualifying the first guideline as “honest communication,” therefore, both the “messages” and the “messengers” (be they persons or organizations) are at stake.

Given our focus on marketing ethics in China, a further question arises about how to understand “honest communication” in the Chinese cultural context that, undoubtedly, deeply influences the ways of communication. How should the characteristics of Chinese communication be taken into account?

As Ge Gao, Stella Ting-Toomy and William B. Gudykunst point out,

[C]ommunication is a foreign concept to the Chinese; no single word in Chinese serves as an adequate translation for the term.…The three most commonly used translations include jiao lu (to exchange), chuan bo (to disseminate), and gou tong (to connect). Gou tong, the ability to connect among people, is the closest Chinese equivalent for communication as it is usually used by Western scholars. (Gao et al. 1996, p. 280 f.)

The authors then identify five characteristics of Chinese communication (pp. 283–292): (1) Implicit communication, which is a mode of communication (both verbal and nonverbal) that is contained, reserved, implicit, and indirect. So one does not spell out everything, but leaves the “unspoken” to the listeners. (2) Listening-centeredness, which reflects an asymmetric style of communication between those who are entitled to speak (parents, teachers, rulers) and those in subordinate positions who are supposed to listen. (3) Politeness, which applies to all interpersonal interactions and concerns all parties involved. (4) The insider effect on communication, based on the distinction between insiders and outsiders, where communication within the group can be very personal and emotional as opposed to that outside the group. (5) Face-directed communication strategies in which face management is essential to maintaining the existing role relationship and preserving interpersonal harmony.

Obviously, when communicating in China, these characteristics have to be taken into account. Do they redefine the understanding of honest communication outlined above? Certainly, they help specify important aspects of honest communication in China. But, in our view, they do not contradict its core meaning of refraining from intentional efforts to mislead people in order to make them act against their will. Bok’s cautioning against multiple errors is particularly relevant for intercultural communication, in which misunderstandings abound. False statements are not necessarily lies. Even many intentionally false statements are not intended to mislead listeners and, therefore, are not deceitful. On the other hand, true statements or even silence are no guarantee for honest communication; neither is implicit communication. They can be meant to deceive nevertheless. Also, deception is possible with listening centeredness where subordinates tend to not voice their views. Despite politeness in language and behavior, listeners can be misled intentionally. The insider effect on communication can be honest within the group and deceitful to outsiders. Face-directed communication strategies can be pursued in order to maintain existing roles and preserve harmony in spite of contradicting evidence.

As “honest communication” encompasses both the message and the messenger, a misleading message can shed light on the messenger and potentially disqualify him or her. In turn, a person of integrity will make sure that his or her message is not misleading. This connection between message and messenger appears particularly important in the Chinese cultural context, which greatly values interpersonal relations as distinct from anonymous market relations. It has to be taken into account when discussing the following cases.

Baidu under fire on ads

The first case is about ethics in e-commerce, a growing concern of China’s rapidly expanding Internet. Baidu, the nation’s dominant search engine, has built its share of China’s search market up to over 70% since Google’s high-profile exit in the year of 2010. In the last few years, Chinese Central Television (CCTV) reported several stories in which Baidu was accused of unethical behavior (see sources of Baidu case):

-

In 2008, CCTV aired an exposé on Baidu selling links to unlicensed medical sites with unproven claims for their products. The company’s Nasdaq-listed shares subsequently fell as much as 40%, and its fourth quarter revenues were 14% below the midpoint of the company’s original forecast, prompting Baidu Chief Executive Robin Li to publicly apologize. Moreover, Baidu had overhauled its operations and sacked staff involved.

-

In 2010, a report by CCTV accused Baidu of promoting counterfeit drugs through its web search engine, a promotion that duped more than 3,000 people in China. The report was aired on Sunday, July 18. Baidu declined to comment on the accusation. As a result, Baidu’s shares fell as much as 4% on Monday.

-

In 2011, CCTV aired a report asserting that Baidu continues to allow sellers of fake medicines to advertisers on the site. The program shows a reporter trying to buy ads for a fake company selling weight loss drugs—and a Baidu staffer aiding the reporter in getting around checks on pharmaceutical advertisers by registering as a machinery company and changing its keywords later. The report also asserts that Baidu’s bidding system for keywords leads companies to bid more than necessary to get high-ranking search results. Since the report was broadcast, shares of the Nasdaq-listed company have lost nearly a tenth of its value, or US $5 billion, in just 2 days.

We now may ask whether and, if so, how did Baidu violate the guideline of honest communication. One could argue that Baidu is only a middleman between the companies who offer the medicines and the patients who seek them, and it is up to either side to take responsibility to sell safe drugs and to do due diligence when buying them. One could add that it is the government’s role and responsibility to enact and enforce laws and regulations in order to ensure the safety of drugs and medicines. So how persuasive are these arguments?

While, undoubtedly, the sellers and buyers as well as the government bear some ethical (and legal) responsibility, this does not mean that the middleman—Baidu in this case—has no ethical responsibility at all. To the extent of its space of freedom, Baidu bears ethical responsibility as well (see Enderle and Murphy 2009, pp. 510–513). The company was instrumental in providing false and potentially harmful information; this undermined, by the way, its reputation as a trustworthy information provider. As the third incident in 2011 indicates, Baidu failed not only by negligence but also by a deficient corporate culture that did not place the needs of the customers ahead of the needs of the marketer. In addition to misleading messages, the integrity of the messenger, that is of the Internet search company, was impaired. In sum, it appears fair to state that Baidu engaged in dishonest communication or, as defined above, participated in “intentional efforts to mislead people in order to make them act against their will.”

Da Vinci labeling domestic goods as foreign

As China has become the manufacturing house of the world and “made in China” products can be found everywhere, a fashionable trend has emerged among Chinese consumers to buy products from developed countries. In particular, newly rich Chinese are eager to shop for high-end luxury goods from abroad. This trend was perceived by Da Vinci, a high-end furniture company in China which sells very expensive furniture. A silk-covered couch, for example, is priced around 110,000 yuan (or US $16,975). Alluding to its name, Da Vinci claimed that its products were made in Italy and manufactured of rare wood (see sources of Da Vinci case).

For half a year, a reporter of CCTV investigated over 100 furniture factories to find the secret of the Da Vinci code: fake production location and counterfeit products. CCTV reported that some of Da Vinci’s expensive furniture labeled as foreign products was not manufactured abroad but in Dongguan, Guangdong province. Moreover, some furniture claimed to be made of rare wood were actually made from polymer and other chemicals and some so-called hand-carved furniture were made by machine.

A salesman of the factory in Dongguan told CCTV that the factory has taken orders from Da Vinci since 2006 and produced three “brands” of furniture—Riva, Hollywood Homes, and Cappelletti. The trade, unknown to the owners of the Riva and Cappelletti brands, totaled about 50 million yuan in 2010. The furniture manufactured for Da Vinci was shipped as “made in China” furniture from Shenzhen’s harbor to Italy and later delivered to Da Vinci’s storehouse in Shanghai as “made in Italy” products. As China Daily later learned, the whistle-blower was sacked by the factory, which stated that “he told lies to the media about our company’s relationship with Da Vinci.”

The Da Vinci story is a relatively clear-cut case and shows that deception can only work as long as people believe that the labeling is truthful. It is noteworthy that the factory’s statement claims to tell the truth by qualifying the whistle-blower as a liar. Obviously, finding out the truth matters.

Carrefour overcharging customers

Honest communication is an issue not only for Chinese companies but also for foreign companies in China. The French retailer Carrefour entered China in 1995 and has now more than 150 stores in various cities (see sources of Carrefour case). On January 26, 2011, the National Development and Reform Commission said in a statement that 11 Carrefour stores and some other retailers were overcharging customers and urged local authorities to take action.

The practices included referring to normal prices as sales prices, charging more than what was listed on price tags and misleading customers with price figures typed in different point sizes. These kinds of overcharging happened all over the country: in three stores in Shanghai, three in Central China’s Hunan province, two in Southwest China’s Yunnan province, two in Guangzhou, and one in Beijing.

The stores were fined up to 500,000 yuan (or approx. US $79,365) each for violating the PRC’s Price Law, a fine which was the highest ever imposed in China for such malpractice. The punishment was accompanied by a blitz of bad publicity both in the local press and on the Internet.

Walmart labeling ordinary pork as organic

In fall 2011, the US retailer was ordered to close seven stores in the city of Chongqing in southwestern China (see sources of Walmart case). A number of store managers were detained, following allegations that employees had labeled ordinary pork as organic.

Since earlier this year a scandal broke involving a toxic additive fed to pigs in China, labeling a meat as organic has become a way of boosting sales. But “the problem in China is we have no central [organic] certification authorities,” Mr. French, a marketing consultant in Shanghai, said. “A thousand pounds in an envelope will get you the certificate you need” (Financial Times 2011).

According to Huang Bo, head of the industry and commerce bureau, Walmart has been punished 21 times in Chongqing since 2006 for violations such as false advertising and mislabeling products. In the latest episode, Walmart was fined 2.69 million yuan (or US $423,548) according to Xinhua, the official Chinese news agency.

As these four cases of Chinese and non-Chinese companies demonstrate, “practicing honest communication” is a first, important guideline for marketing ethics in China. The examples discussed are relatively straightforward. Although all of them occurred in China, their ethical issues at stake do not appear to be basically altered by the Chinese cultural characteristics mentioned above. Moreover, they can be legislated, and they are to some extent, but the strictness and the enforcement of the legislation certainly leave room for improvement. In more complex situations, the discernment of honest communication might be more difficult and harder to legislate. All the more important becomes the ethical commitment that is required from companies.

Enhancing human capabilities

While communication between persons and organizations is fundamental to any business and marketing activity, it does not answer the question of its purpose itself. Communication for the sake of communication does not suffice. Therefore, we should ask directly about the purpose and objectives of these activities. These answers, of course, vary greatly according to the specific circumstances and levels from very specific to very general objectives. The following guidelines necessarily are quite general. They relate to the three basic categories: “people,” “culture,” and “nature.”

As for the category of “people,” the term “human development” will be used here, which, according to the definition of the United Nations Development Program, can be applied to any situation in developing and developed countries and, therefore, is much more operational. The short definition of “human development” is “to enlarge people’s choices”, which basically involves longer life expectancies and economic as well as educational improvements. It takes a “humanitarian” perspective that primarily considers human beings as ends rather than mere means.

Amartya Sen’s “capability approach” can further clarify the concept of human development (see Sen 1999, 2009; Enderle 2012a). It is guided by the idea that each human being should have the freedom to achieve well-being. Well-being is assessed by the concept of “functionings,” while freedom to pursue well-being is conceptualized by “capabilities.”

The relevant functionings can vary from such elementary things as being adequately nourished, being in good health, avoiding escapable morbidity and premature mortality, etc., to more complex achievements such as being happy, having self-respect, taking part in the life of the community, and so on. (Sen 1992, p. 33)

Living is seen as a set of interrelated functionings of persons, consisting of their beings and doings. Closely related is the notion of capability to function, which represents the various combinations of functionings and reflects the person’s freedom to lead one type of life or another. In other words, the person’s freedom and empowerment imply not only having the choice but also having the capacity to exercise that choice.

The second guideline requires the enhancement of human capabilities. If the concept of marketing aims at preserving and enhancing the customer’s and society’s well-being (as Philip Kotler’s concept of societal marketing demands), it also needs a clear and operationable understanding of well-being. The capability approach greatly helps in clarifying and strengthening this understanding.

OTIS escalator safety in spotlight

OTIS, the world’s leading elevator and escalator manufacturer, was put in the spotlight when a 13-year-old boy was killed and 30 others injured, three seriously, because a “crowded” ascending subway escalator suddenly reversed direction (see sources of OTIS case). The escalator accident occurred on July 5, 2011 at the Beijing Zoo Station Exit A on Line 4. Since this line opened on September 28, 2009, it has carried 400 million passengers until May 2011.

Photographs by witnesses posted online showed discarded shoes, bags, and flattened bottles scattered at the bottom of the escalator. Several people, lying or sitting on the bloodstained floor, were being helped and comforted by members of the public. Fu Jinyuan, one of the injured, recalled the moment when the escalator malfunctioned while receiving treatment at Peking University People’s Hospital. “First there was a crashing sound, then the rising escalator started going down. Then wave after wave of people began falling. I thought I was finished” (China Daily 2011).

Based on its initial investigation, the Beijing Bureau of Quality and Technical Supervision said the OTIS 513 MPE had design flaws and the company was inescapably responsible for the accident.

This was not the first OTIS escalator accident recently in China. On March 25, 2011, 61 children were injured when an escalator suddenly stopped within the Wuxi Zoo in Jiangsu province. On December 14, 2010, 24 passengers were injured when an escalator also reversed direction in a Shenzhen subway station in Guangdong province.

As these accidents show, the safety of escalators (and one may add, of elevators) has become a very sensitive issue and affects a growing urbanized population which experiences steady advances in mass transportation. People demand nothing less than zero tolerance for failure, and companies in the escalator and elevator industry are well advised to put safety above all profit considerations (as, for example, KONE Corporation does; www.kone.com). Safety standards for escalators and elevators should not depend on particular cultural attitudes or specific levels of economic development. There are no “Chinese” standards versus “American” or “European” standards. Rather, the standards are about human life, or, in terms of Sen’s capability approach, what is at stake is people’s capability of being transported safely without threat of being injured or killed.

Working conditions at Foxconn led to ten suicides of young workers

From January to May 2010, Foxconn’s factory in Shenzhen witnessed a rash of suicides whereby 12 workers jumped from the tops of buildings, ten of them to their deaths (see sources of Foxconn/Apple case). Taiwan-registered Foxconn is the world’s largest electronics maker, with more than 920,000 employees (2010), including 300,000 in Shenzhen; it is a major supplier of Apple. The young workers (between 18 and 24 years old) were desperate, feeling like machine parts in an assembly line, reliant on long hours of overtime to scrape together a meager salary. They belonged to the second generation of migrant workers who have a lower salary compared with their parents’ generation (when adjusted for cost of living then and today).

For example, the breakdown of a Foxconn worker’s paycheck in November 2009 was as follows (The Other Side of Apple, 2011, p. 16):

Basic salary for 21.75 normal workdays | 900 yuan (approx. US $135) |

Normal overtime 60.5 h for overtime pay | 469 yuan (approx. US $68) |

Weekend overtime 75 h for overtime pay | 776 yuan (approx. US $110) |

Total pay | 2,145 yuan (approx. US $313) |

These suicides and the miserable working conditions provoked vehement and widespread reactions in the media not only against Foxconn but also against Apple. They shed a glaring light on the violation of the basic dignity of workers and their labor rights. In terms of Sen’s capability approach, the workers lacked the capabilities of earning a decent livelihood, enjoying a reasonable amount of leisure time, being mentally healthy, not suffering from unbearable stress, and being respected as a human being, in addition to other capabilities.

Not only Foxconn but also Apple was held ethically responsible for these wrongdoings, the first as immediate perpetrator and the second because of its powerful position in the supply chain. Although Apple did not formally accept responsibility, it responded to the suicides at Foxconn in multiple ways, summarized in a special section of the Apply Supplier Responsibility 2011 Progress Report (pp. 18–19). In June 2010, Apple COO Tim Cook and other Apple executives visited the Shenzhen factory and met with Foxconn CEO Terry Gou. In July 2010, an independent team of experts investigated the circumstances of the suicides, and in August 2010, it presented its findings and recommendations. The recommendations included psychological help such as counselors, a 24-h care center, better hotlines, an employee assistance program, and even large nets to the factory buildings “to prevent impulsive suicides”; however, economic improvements were not mentioned.

Fostering creative intercultural diversity

The third guideline further develops the second one by explicitly addressing the crucial, yet often overlooked, role of cultural diversity in international business and marketing. Based on the UNESCO Report (1995), three fundamental culture-related features can be identified:

-

Culture is more than a mere means to achieve economic growth. “Culture’s role is not exhausted as a servant of ends—though in a narrower sense of this concept this is one of its roles—but is the social basis of the ends themselves” (UNESCO 1995, p. 15). Hence, it follows that marketing should not use culture merely as a means to achieve economic growth.

-

Cultural growth needs to be promoted actively. “Culture is the foundation of our progress and creativity. Once we shift our view from the purely instrumental role of culture to awarding it a constructive, constitutive, and creative role, we have to see development in terms that encompass cultural growth” (UNESCO 1995, p. 15). Hence, the question arises as to what marketing can and should contribute to cultural growth.

-

Although the global context includes an immense variety of cultures, the focus on economic globalization tends to ignore this rich variety and imposes a new kind of “cultural imperialism.” As a reaction to this trend, “cultural isolationism” arises in many countries, which rejects any influence from abroad. Therefore, both respect for other cultures and the will to learn from them are necessary to foster creative intercultural diversity. Hence, marketing faces the challenge of resisting global pressures and avoiding global neglect, which threaten the peoples’ capability to define their own basic needs.

illycaffe promoting a culture of coffee in China

Since ancient times, China has cherished a culture of tea so that, today, one can find hundreds of sorts of tea with an incredible range of taste—some sorts may cost thousands of yuan for 100 g—comparable to the abundance of sorts of grape vines. In contrast, the development of a culture of coffee in China is in its infancy. Only an average of 25 g of coffee per person per year are consumed in this country, which is a huge contrast to other countries such as the USA with 8 kg and Finland, the leader in coffee consumption, with 13 kg.

Therefore, it takes a great deal of courage and entrepreneurship to build up a coffee culture in China. In fact, the Italy-based company illycaffe, founded by Francesco Illy in 1933, pursues the bold mission “to produce the best coffee in the world” by generating value for all the stakeholders involved (see sources of illycaffe case). Each must be able to draw satisfaction and benefits: economic, social, and environmental benefits for the consumers, the customers, the collaborators, the suppliers, and the community with which the company interacts and, finally, the shareholders. illycaffe exports to over 140 countries in all five continents. It established “the University of Coffee” in Trieste with branches throughout the world, including a “University” in Shanghai (in 2006). “The courses are structured in relation to the public they address: coffee growers; entrepreneurs and bar staff, restaurants and hotels; consumers and curious enthusiasts, all of them attentive and keen on increasing their knowledge of the world of coffee” (www.illychina.com). In 2001, under the name of Shanghai Fortunecaffee, illycaffe entered mainland China and became a joint venture with illycaffe s. p. a. in 2006. It has now 16 sub-dealers around the country.

In its endeavor to spread the coffee culture in China, illycaffe does not consider Starbucks a competitor. Rather, it welcomes Starbucks with its aggressive expansion as a trailblazer while remaining convinced that its own blend is the best in the world and will persuade more and more Chinese consumers, thanks to its superior quality.

Given illycaffe’s outstanding products, innovative policies, aesthetic sensitivity, sustainability focus, and ethical culture, it appears fair to say that this company makes a valuable contribution to China’s cultural diversity. It respects the traditional tea culture. At the same time, it enriches the Chinese consumers’ choices by offering high-end coffee produced in a sustainable fashion.

Fuda’s “good people” culture with Chinese characteristics

Shanghai Fuda Group, a medium-sized company in the conveyor belt industry, was founded by Mr. Li Yuan in 1992 and has developed, under his leadership, as a successful role model of a Chinese private enterprise that has put into practice its economic, social, and environmental responsibilities in many innovative ways (see Lu et al. 2012). The drive to innovation has deeply shaped Yuan’s understanding of the entrepreneur’s mission, Fuda’s strong “good people” culture, its products and processes, its well-conceived responsibilities toward stakeholders, and its organizational structures. Over the years, the company has received an impressive range of awards and recognitions.

Fuda can be seen as an outstanding example to illustrate in many respects the third guideline “to foster creative intercultural diversity.” The company’s culture is not only a means to achieve economic growth but is also the foundation of its identity and purpose. With foresight and persistence, it has been developed and enriched over 20 years and thus outlived by far the average 4-year life span of Chinese private enterprises. It has successfully avoided both being “colonialized” by globalization and being “insulated” within a narrow traditional Chinese mindset.

Intercultural diversity is manifest in Fuda’s promoted ethical virtues and values. According to Yuan, the entrepreneur has to be a person with a high spirit of innovation, professionalism, and a sense of social responsibility, exemplifying the four Chinese “Qis”, namely, magnanimity (daqi), loyalty to friends (yiqi), a sense of chivalry (xiaqi), and amity or harmony (heqi). At the same time, the “good people” culture advocates and incorporates the universal values of kindness, trustworthiness, and gratitude, which are expected from everybody in the company, from the president and the managers to the shop floor workers.

These ethical virtues and values are specified in Fuda’s responsibilities toward suppliers, customers, employees, society, and nature and permeate its organizational structures. To be nice to suppliers entails relations based on mutual respect to ensure fairness and truthfulness in terms of pricing, purchasing, bargaining, quality, competitiveness, and reputation. With the help of “conferences of qualified suppliers,” long-term and stable cooperative relations have been established. In the course of opening markets and maintaining customer relations, Fuda has gradually formed persuasive and effective marketing policies by providing high-quality products and service in accordance with the requirements of customers; by launching perfect after-sales services and modifying products and management strategies in a timely fashion, if needed; and by establishing stable social relations and ties with customers by family-oriented and user-friendly efforts in order to consolidate aggressively and expand steadily the customer base through benign interactions.

As Yuan has often recalled, networking with all stakeholders is of vital importance, particularly in the Chinese context where guanxi (that is, relationships) play a central role. It is precisely this focus on relationships which indicates why ethical virtues and values matter so much. They have to be practiced while accounting for the characteristics of Chinese communication discussed above.

Intercultural diversity, furthermore, comes to the fore in Fuda’s organizational structures. While the company is a modern private joint-stock company subject to the market forces, the people orientation has led to the expansion of the employees’ economic and social rights within the company and to the creation of a cooperative system with harmonious capital–labor relations (comparable to the “social partnership” between capital and labor in Germany’s social market economy). Building up the dominant position of employees, Yuan has followed the Chinese saying that “rivers (i.e., companies) are full as long as creeks (i.e., employees) have water,” which means Fuda can be rich only if its employees become rich. In other words, it is about “storing wealth into the mass.” This arouses the enthusiasm of the employees and motivates them to do their best to develop the enterprise actively and positively as one person.

In the pursuit of sharing wealth, several provisions were introduced: 50% of profit sharing with employees in the form of bonuses; general wage raises every 2 years; a management buyout to form independent affiliates with their own leaders; and a democratic procedure to elect the president of the company group.

Surprising to Western and even Chinese observers is the establishment of a number of committees across Fuda which follow some management practices of traditional state-owned enterprises (inspired by Yuan’s former experience in the state-owned Shanghai Rubber Belt Factory). Although the company is a private enterprise, it has a council of worker representatives (in addition to the council of shareholder representatives), a labor union, and even a committee of the Communist Party of China. The justification of this organizational structure lies in the “good people” culture. The stronger this culture is, the more decentralized the organization can be and the more employees can be empowered to participate in the company’s endeavors.

In sum, Fuda represents an excellent example of using its space of freedom to the fullest extent possible and assuming its responsibilities with great imagination in order to combine Chinese traditional culture, universal values, and modern management and marketing practice.

Promoting sustainable growth and eco-efficiency

Given the increasing ecological awareness and debate around the world, it becomes almost a truism that all economic activities are intrinsically and inescapably embedded in nature. Whatever decision economic actors make and whatever action they take is related to the “environment.”

Fortunately, there now exists a widely, at least theoretically, accepted general standard of environmental soundness. The World Commission on Environment and Development defines “sustainable development” as a style of progress or development that “meets the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED 1987, p. 8). Growth, then, will have to be extremely “eco-efficient,” which combines economic and ecological efficiency. It is “a process of adding ever more value while steadily decreasing resource use, waste, and pollution (Schmidheiny and Zorraquin 1996, p. 5).

In order to operationalize sustainability and eco-efficiency, many proposals have been made including early ones by Van Dieren (1995), Schmidheiny and Zorraquin (1996), Hammond et al. (1995), and the Sustainability Guidelines of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), which have been continuously improved since 1997. It is fair to say that today, a great range of environmental tools and strategies are available for those who want to commit themselves to sustainability and eco-efficiency.

Baosteel and Haworth—champions of environmental responsibility

To illustrate the growing acceptance and use of the GRI Sustainability Guidelines, two examples are presented briefly: Baosteel or Baoshan Iron & Steel Co., Ltd., and Haworth, in particular Haworth Asia Pacific.

Baosteel, headquartered in Shanghai, is a state-owned enterprise founded by Deng Xiaoping in 1978, which has become the second largest steel producer in the world in 2011 (see sources of Baosteel case). It started publishing annual environmental reports in 2003. From 2005 on, it compiled the annual Sustainability Report in accordance with the GRI Sustainability Guidelines (the G3 version since 2007). It mainly addresses economic, environmental, social, and other activities of Baosteel and its 13 branches and subsidiaries.

The 2010 Sustainability Report (accessible on Baosteel’s web site) includes 18 chapters on topics such as governance structure, management improvement, anti-corruption, innovation development, harmonious development, and social responsibility. The chapter on environmental protection (pp. 38–48) is particularly relevant with regard to the fourth guideline. It begins with the statement that “our goal is to build a global leading clean steelmaker.” Although the term of eco-efficiency is never used, the idea of combining economic and ecological efficiency clearly runs all the way through the chapter regarding management guidelines, management structure and responsibilities, the systems of environmental and energy management, and education and training thereof. As for the concept of sustainability as defined by the World Commission on Environment and Development, neither this chapter nor the report in general addresses this issue. It only speaks of enhancing Baosteel’s “sustainable” core competitiveness and building the company into the world’s most competitive steelmaker” (pp. 3, 4).

Haworth International, Inc. is a privately held global corporation headquartered in Holland, Michigan, USA, serving the contract market with furniture and workspace interiors (see sources of Haworth case). The division of Asia Pacific, Middle East, and Latin America is headquartered in Shanghai. Haworth has a strong sustainability vision that goes beyond eco-efficiency. Processes must be neutral or improve the environment. Haworth strives to balance economic, social, and environmental responsibilities. It describes its inspiration as “nature, science and a commitment to future generations” and defines its commitment as “our sustainability journey.” “Haworth will be a sustainable corporation.” “As always, there is more to do, yet we are pleased with our progress” (Haworth 2011, pp. 1, 2).

Like Baosteel, Haworth started publishing annual sustainability reports in 2005 with consideration for the GRI Sustainability Reporting Guidelines. In its 2010 Report, it explicitly highlights GRI content throughout the document. In addition to social responsibility and stakeholder engagement, environmental responsibility plays a particularly important role and is explained in great breadth and depth, covering sustainable products and workplace design, energy management, green transportation, zero waste and emissions, and green building and sustainable site management. While there is certainly still room for improvement, Haworth has made great strides toward a sustainable corporation.

Pollution spreads through Apple’s supply chain

While Baosteel and Haworth can be seen as champions of environmental responsibility, sharp criticism has been raised against Apple and its suppliers in China by a group of Chinese environmental non-governmental organizations (NGOs; see sources of Apple case). As already mentioned in the Foxconn case, the IT industry investigative report, The Other Side of Apple, was published on January 20, 2011, accusing Apple of violating, in its supply chain, not only occupational safety and labor rights and dignity but also seriously harming the environment. Apple responded to those accusations, to some extent, in its Apple Supplier Responsibility 2011 Progress Report (February 2011), but did not explicitly address the criticism concerning environmental wrongdoings. In August 2011, a second report, The Other Side of Apple II, followed, focusing entirely on the spread of pollution through Apple’s supply chain. Ten case studies were presented that revealed the following malpractices: shocking levels of environmental pollution, causing direct harm to the community, huge amounts of hazardous waste leaving hidden dangers for China, more pollution records in Apple’s supply chain, and Apple’s audits covering up bloodstained production. Three months later, five Apple employees met with nine representatives of the NGOs’ report in Beijing.

Although the controversy is not settled yet (as of the end of November 2011), one can already discern several ethical challenges. As Apple continues to expand, its environmental impact, outsourced to China and other countries, becomes greater and more unmanaged. At the same time, internal opposition in China is growing through aggressive environmental groups and green coalitions like the Green Choice Initiative, which includes already about three dozen NGOs. Apple has to decide how seriously it wants to engage in stakeholder dialogue. Given its power to control the production processes of its suppliers and its dominance over the distribution of profits, it has to make up its mind to what extent it should take responsibility for the environmental as well as social and economic impact in its supply chain. Having publicly stated its commitment to “driving the highest standards of social responsibility throughout our supply base” and that its suppliers “use environmentally responsible manufacturing processes wherever Apple products are made” (2011 Progress Report, p. 3), Apple bears the ethical obligation to live up to those standards. Moreover, while many other IT companies operating in China actually disclose the names of their suppliers, Apple maintains a culture of “secrecy” and has refused to disclose its suppliers. The discrepancy between Apple’s public commitment and actual environmental performance and the lack of transparency amount to deceiving its customers and other stakeholders, thereby violating the guideline of honest communication.

ConocoPhillips’s oil spill in China’s Bohai Bay

In summer 2011, an oil spill from an offshore field operated by ConocoPhillips China, a subsidiary of the Houston-based energy company ConocoPhillips, lasted 3 months, leaked about 3,200 barrels of oil and mud from oil, and polluted at least 5,500 km2 (or 2,124 square miles). It was China’s worst offshore accident, although not its worst oil spill, which happened in 2010 in a PetroChina port facility in the city of Dalian and amounted to more than 11,000 barrels of oil (or, according to Greenpeace, to 430,000–650,000 barrels of oil).

To understand the backdrop of this offshore accident, one may recall a couple of circumstances. With its booming economy, China is in urgent need for new energy resources. The oil field in the Bohai Bay, discovered in 1999, is one of the largest in China. Lacking up-to-date technology, China has lured foreign companies such as ConocoPhillips, Anadarko, BP, and Husky Energy to form joint ventures with China National Offshore Oil Corporation (Cnooc). So the offshore Peng Lai oil field is run in a venture that gives Cnooc 51% ownership and ConocoPhillips a 49% stake as operator. Because of a series of environmental disasters such as the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear meltdown in Japan, environmental awareness has significantly risen in China, as in other parts of the world. Moreover, lagging somewhat behind, the state regulators have become stricter and set tougher rules for offshore drilling, and foreign companies are a ready target.

Without investigating the case in further detail, one can discern the following ethical challenges. First, it is imperative to realistically assess the extent and seriousness of the oil spill as it is unfolding in each phase. Second, the ethical responsibilities of all major actors involved in the spill have to be clearly identified as well as the ways they are to be shared in joint ventures between majority shareowner and operator, between regulators and regulated firms and industries, between the media, academia, NGOs, and other actors in society. Third, the involved companies and regulators must disclose all the relevant facts in a timely and honest way in order to restore and maintain trust in the population. Fourth, appropriate measures have to be taken to repair the harm inflicted on people and nature and to prevent similar disasters in the future.

Conclusion

With the help of four ethical guidelines and several positive and negative concrete examples of Chinese and non-Chinese companies, we have attempted to provide a broad and timely, but far from complete, view on marketing issues in China and to discern their ethical challenges. Admittedly, most of these cases are relatively straightforward and not too hard to address. But we hope they can help clarify some basic concepts and lay a solid foundation for further developing marketing ethics in the Chinese context.

We may conclude by indicating a few perspectives for further development. First, the very concept of marketing is of paramount importance for a well-founded understanding of marketing ethics. If marketing is conceived in a strictly instrumental way or as a body of merely logistic knowledge (that is what Amartya Sen calls an “engineering approach”), ethical guidance can come only from “outside” the field and expertise of marketing. A more promising and more realistic concept follows an “ethics-related approach” in which intrinsic values, human motivations, and the assessment of social results play an indispensable role “within” marketing.

Second, marketing ethics cannot consist in hopping from case to case and offering nothing more than case solutions. Rather, more systematic efforts are needed. For this purpose, “mid-level principles” should be elaborated, which are determined by both general ethical principles and practical and theoretical marketing expertise. In such a way, a robust concept of marketing ethics can, so to speak, “walk on two legs.”

Third, to understand the ethical dimension in mid-level principles, it will be crucial to distinguish three kinds of ethical obligations; otherwise, there is confusion in talking about “ethics”, demanding “ethical conduct” from companies, or blaming marketers for “unethical behavior.” The first includes basic ethical norms such as not to deceive customers; the second involves positive obligations beyond the minimum, for instance, to respect and support in principle a host country’s culture; and the third relates to the aspiration for ethical ideals, which, for example, may mean a company taking a leadership role in promoting sustainability. This distinction provides a more sophisticated understanding of “ethics and values” and is particularly relevant in international business and marketing in which the search for both a common ethical ground and the respect for pluralism is quite complex and difficult.

Finally, marketing ethics should not content itself with analyzing its challenges in ethical and marketing terms. As the very understanding of ethics requires, it is about what we ought to do. Its ultimate purpose is to recommend thought-through and practice-tested solutions for the multifarious challenges of marketing ethics. Undoubtedly, like any other country, China needs this commitment.

Notes

In 2010, consumer retailing goods reached a total of 15.7 trillion yuan (US $2.47 trillion) according to the Bulletin on the National Economy and Social Development (http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjgb/ndtjgb/qgndtjgb/t20110228_402705692.htm).

Literature on marketing ethics in general: Brenkert (2008), Enderle and Murphy (2009), Laczniak and Murphy (1993), Murphy et al. (2005), Singhapakdi and Vitell (1999), Vitell (2001). Literature on business ethics in China: Enderle (1997, 2003, 2005, 2010, 2012), Enderle and Lu (2012), Lu (1997, 2009, 2010), Lu and Enderle (2006), Niu (1997), Paine (2010), Thompson (2009), Zhou et al. (2009), Zhou (2011).

References

Bok, S. (1992). Deceit. In L. Becker & C. Becker (Eds.), Encyclopedia of ethics (pp. 242–245). New York: Garland.

Brenkert, G. G. (2008). Marketing ethics. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

China Watch (2011). China Daily, November 10 (Advertisement inserted in Financial Times, November 10, 2011).

Enderle, G. (1997). Ethical guidelines for the reform of state-owned enterprises in China. University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Economic Law, 18(4), 1177–1192.

Enderle, G. (1998). A framework for international marketing ethics: Preliminary considerations and emerging perspectives. Journal of Human Values (New Delhi), 4(1), 25–44.

Enderle, G. (2003). What perspectives for developing business ethics in China? In K.-T. Ip (Ed.), Market economy and corporate ethics (pp. 1–15). Shanghai: Fudan University Press (in Chinese).

Enderle, G. (2005). Business Ethics in China. In P. H. Werhane and R. E. Freeman (Eds.) (2005). Blackwell encyclopedia of management. Volume business ethics, 2nd ed. (pp. 76–80), Oxford: Blackwell.

Enderle, G. (2010). Wealth creation in China and some lessons for development ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 96(1), 1–15.

Enderle, G. (2012). The capability approach as guidance for corporate ethics. In C. Luetge (Ed.), Handbook of the philosophical foundations of business ethics. Dordrecht: Springer (in press).

Enderle, G. & Lu, X. (2012). Business ethics in China. In D. Koehn (Ed.), Wiley encyclopedia of management. Volume business ethics, 3rd ed.. Hoboken: Wiley (in press).

Enderle, G., & Murphy, P. E. (2009). Ethics and corporate social responsibility for marketing in the global marketplace. In M. Kotabe & K. Helsen (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of international marketing (pp. 504–531). Los Angeles: Sage.

Gao, G., Tong-Toomy, S., & Gudykunst, W. B. (1996). Chinese communication processes. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 280–293). Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Hammond, A., Adriaanse, A., Rodenburg, E., Bryant, D., & Woodward, R. (1995). Environmental indicators: A systemic approach to measuring and reporting environmental policy performance in the context of sustainable development. New York: World Resources Institute.

Laczniak, G. R., & Murphy, P. E. (1993). Ethical marketing decisions: The higher road. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Liu, C., Peng, J., Pei, Y., & Gu, Y. (2011). What makes the Chinese fraud stocks listed in the U.S. so outrageous? Research paper in the MBA course “Professional Ethics and Integrity” in June 2011, SAIF, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai.

Lu, X. (1997). Business ethics in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 16, 1509–1518.

Lu, X. (2009). A Chinese perspective: Business ethics in China now and in the future. Journal of Business Ethics, 86, 451–461.

Lu, X. (2010). Business ethics. A Chinese perspective. Shanghai: Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press.

Lu, X., & Enderle, G. (Eds.) (2006). Developing business ethics in China. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Murphy, P. E., Laczniak, G. R., Bowie, N. E., & Klein, T. A. (2005). Ethical marketing. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education.

Niu, Q. (1997). Studies of marketing ethics. Journal of China Business and Market, No. 6, ISSN 1002-8811(1007-8226) (in Chinese).

Paine, L. S. (2010). The globe. The China rules. Harvard Business Review (June).

Ryan, L. V., Gasparski, W. W., & Enderle, G. (2000). Business students focus on ethics. Praxiology: The international annual of practical philosophy and methodology, vol. 8. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Santoro, M. A. (2009). China 2020: How Western business can—and should—influence social and political change in the coming decade. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Schmidheiny, S., & Zorraquin, F. J. L. (1996). Financial change: The financial community, eco-efficiency, and sustainable development. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sen, A. (1992). Inequality reexamined. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. New York: Knopf.

Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Singhapakdi, A. & Vitell, S. J. (Eds.). (1999). International marketing ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 18, 1 (January 1).

Thompson, M. J. (2009). Integrity in marketing: Chinese and European perspectives. Journal of International Business Ethics, 2(2), 62–69.

UNESCO (1995). Our creative diversity. Report of the World Commission on Culture and Development, Egoprim, France.

Van Dieren, W. (Ed.) (1995). Taking nature into account. A Report to the Club of Rome. New York: Springer.

Vitell, S. J. (Ed.) (2001). Special issue on marketing ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 32, 1 (July I).

World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). (1987). Our common future. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wu, M., Zhang, J., Xiang, K., & Shi, L. (2011). Double standards in marketing practices of multinationals in China—The cases of Nestle, HP and Toyota. Research paper in the MBA course “Professional Ethics and Integrity” in June 2011, SAIF, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai.

Zhou, Z. (2011). Business ethics as field of training, teaching and research in East Asia. In D. Rossouw (Ed.), A global survey of business ethics as field of training, teaching and research. Journal of Business Ethics (in press).

Zhou, Z., Ou, P., & Enderle, G. (2009). Business ethics education for MBA students in China: Current status and future prospects. Journal of Business Ethics Education, 6, 103–118.

Zhou Z., Liu Y., & Luo, N. (2010). Economic and business ethics in China: Training, teaching and research. Paper presented at the Third Shanghai International Conference on Business Ethics, SASS Center for Business Ethics, October 29–30, 2010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Sources of Case Studies

Alibaba

February 21, 2011: Alibaba executives resign after rise in fraud cases, BBC: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-12521833

February 21, 2011: Alibaba.com chief executive resigns, Guardian: http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/feb/21/alibaba-chief-resigns-over-frauds

February 22, 2011: Alibaba execs resign over supplier frauds, China Daily: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2011-02/22/content_12053723.htm

February 24, 2011, Alibaba’s Chief Lu Wants to ‘Fix Mistakes, Prevent Detours’, Bloomberg Business Week: http://www.businessweek.com/news/2011-02-24/alibaba-s-chief-lu-wants-to-fix-mistakes-prevent-detours-.html

Apple

July 6, 2010: Clues in an iPhone autopsy. A supply chain with costs rising at each Stop. The New York Times Business, p. B1.

October 2010: Greening Supply Chains in China: Practical Lessons from China-Based Suppliers in Achieving Environmental Performance. Working Paper by Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs and World Resource Institute.

January 20, 2011: The Other Side of Apple. Report by Friends of Nature, Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, and Green Beagle.

February 2011: Apple Supplier Responsibility. 2011 Progress Report: www.apple.com/supplierresponsibility.

August 31, 2011: The Other Side of Apple II. Pollution Spreads Through Apple’s Supply Chain. Report by Friends of Nature, Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, Green Beagle, Envirofriends, and Green Stone Environmental Action Network.

September 1, 2011: Apple accused of using Chinese suppliers with pollution record. Financial Times, p. 11.

September 1, 2011: Foxconn tackles pollution claims. Finance Times, p. 12.

October 2011: Apply faces internal opposition in China. Ethical Performance, Vol. 13, No. 5, p. 12.

November 16, 2011: (Five Chinese environmental protection groups met with Apple), Business and Human Rights Resource Center: www.business-humanrights.org.

Baidu

July 19, 2011, Reuters: http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/07/19/us-baidu-idUSTRE66I1HK20100719

August 16, 2011, Forbes: http://www.forbes.com/sites/ericsavitz/2011/08/16/baidu-slides-after-china-tv-finds-ads-for-fake-meds/

August 17, 2011, Reuters: http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/08/17/us-baidu-cctv-idUSTRE77G14X20110817

August 18, 2011, CTTV: http://english.cntv.cn/program/bizasia/20110818/106379.shtml

video: http://english.cntv.cn/program/bizasia/20110818/105780.shtml

November 2, 2011, CTTV: http://app1.vote.cntv.cn/viewResult.jsp?voteId=3392&score=0

Baosteel

Baosteel. 2011. 2010 Sustainability Report. Baoshan Iron & Steel Co., Ltd. Better Steel, Better Environment, Better Life: www.baosteel.com.

Carrefour

February 11, 2011: Authorities fine French retailer for using misleading price tags, fake discounts to attract customers, China Daily European Weekly.

February 26, 2011: 'Reselling' claims put more pressure on Carrefour. China Daily.

ConocoPhillips

July 5, 2011: China admits extent of spill from oil rig. New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/06/world/asia/06china.html?ref=asia.

July 13, 2011: Update on Bohai Bay oil cleanup and production curtailment. ConocoPhillips Newsletter: http://www.conocophillips.com.cn/EN/newsroom/newsreleases/Pages/20110713.aspx.

August 9, 2011: ConocoPhillips slow to clear up oil spill in China’s Bohai Sea. The Guardian: http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2011/aug/09/conocophillips-oil-spill-china..

August 25, 2011: China to sue ConocoPhillips over oil spills. New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/26/world/asia/26china.html.

August 27-28, 2011: China hits Conoco on spill. The Wall Street Journal, p. B3

September 1, 2011: ConocoPhillips: Bohai oil spill cleanup 99 percentage complete. CCTV English news: http://english.cntv.cn/program/china24/20110901/102701.shtml.

September 7, 2011: China taking a harder line on pollution after Conoco spill. Financial Times, p. 19.

September 19, 2011: Chronology-ConocoPhillips oil spill in China’s Bohai Bay, Reuters: http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/09/19/china-conoco-spill-idUSL3E7K60J320110919.

Da Vinci

July 11, 2011, China Daily: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/metro/2011-07/15/content_12913165.htm

July 12, 2011, China Entrepreneur Magazine (in Chinese): http://www.iceo.com.cn/shangye/36/2011/0712/223742.shtml

July 19, 2011, China Daily: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/bizchina/2011-07/19/content12930222.htm

Foxconn/Apple

May 27, 2010: Apple, HP and Dell investigate Foxconn. Financial Times, p. 1.

May 29, 2010: Foxconn to raise staff salaries by 20% after spate of suicides. Financial Times, p, 1.

May 29, 2010: Showing the strain. Financial Times, p. 5.

June 8, 2010: Foxconn wants clients to share wages burden. Financial Times, p. 16.

June 26, 2010: Chinese pay rises encourage move to cheaper provinces. Financial Times, p.

June 29, 2010: Foxconn to shift Apple gadgets production. Financial Times, p. 1.

January 20, 2011: The Other Side of Apple. Report by Friends of Nature, Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, and Green Beagle.

February 2011: Apple Supplier Responsibility. 2011 Progress Report: www.apple.com/supplierresponsibility.

February 16, 2011: China pays a high cost for Apple’s success. Shanghai Daily, p. A2.

September 13, 2011: Foxconn effect sparks change in direction. Financial Times, p. 3.

Fuda

Lu Xiaohe, Gu Xunli and Xiangqin Chen: 2012, Corporate Responsibilities: Searching the Standards for China’s Small and Medium Enterprises. A case study of Shanghai Fuda (Group) and a comparative study with international standards of corporate responsibilities (Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, Shanghai).

Haworth

Haworth. 2011: 2010 Sustainability Report: www.haworth.com.

Haworth Asia Pacific: www.haworth-asia.com.

illycaffe

illy Branding 2009 (illy information)

illy Marketing Communication Activity 2009 (illy information)

illycaffe Questions and Answers 2010 (illy information)

illycaffe: Beauty has a Taste 2011 (illy information)

Jilin

November 15, 2005: Five dead, one missing, nearly 70 injured after chemical plant blasts, People's Daily Online: http://english.people.com.cn/200511/15/eng20051115_221428.html

November 23, 2005: Toxic leak threat to Chinese city, BBC: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/4462760.stm

November 27, 2005: China's Toxic Shock, Time Magazine: http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1134807,00.html

November 28, 2005: The World's Toxic Waste Dump Choking on Chemicals in China, Spiegel: http://www.spiegel.de/international/spiegel/0,1518,387392,00.html

OTIS

July 6, 2011: Subway escalator crush kills boy, China Daily: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/usa/epaper/2011-07/06/content_12845709.htm

July 14, 2011: Escalator safety in spotlight, China Daily: http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2011-07/14/content_12900424.htm

July 19, 2011: Going down: OTIS share prices fall after elevator accident, China Daily:

http://www.wantchinatimes.com/news-subclass-cnt.aspx?cid=1102&MainCatID=&id=20110719000039

Walmart

October 11, 2011: China shuts seven Walmart stores in pork row. Financial Times, p. 13.

We would like to thank Patrick E. Murphy for his idea to apply the framework for international marketing ethics to China.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Enderle, G., Niu, Q. Discerning ethical challenges for marketing in China. Asian J Bus Ethics 1, 143–162 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-011-0014-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-011-0014-0