Abstract

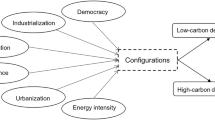

Drawing from the existing social science literature, we examine the relationship between fossil fuel use and the adoption of policy to address climate change at the local level. In our analysis, we incorporate direct measures of fossil fuel use in a manner that allows us to distinguish carbon emissions from consumption-based and production-based activities. Focusing on the 36 most populous and urbanized counties within the state of California, we merge these emissions, along with other political and economic measures, with an indicator of extensive policy support derived from climate agreement signatories. We then use fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to examine conditions that are sufficient for broad adoption of climate policy within a given county. Based on the results, we frame consumption-based and production-based emissions as distinctive in the way that their relationship with climate policy adoption depends on other favorable political and economic conditions. In particular, we identify several routes to extensive adoption for counties that have a combination of low emissions and a favorable political environment. In the conclusion, we discuss the QCA findings and elaborate on the theoretical and practical implications for efforts to understand and to promote carbon reduction efforts at the local level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

San Francisco is removed from the analysis because, unlike all other counties in the state, the city is coterminous with the county and is governed by a consolidated city-county government.

Both the raw dataset analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

While interesting work has been done measuring political support for mayors who sign analogous climate commitments in a European context (see, for example, Martelli et al. 2018), we focus our analysis on the local characteristics that are conducive to the adoption of climate policy in the context of a single US state.

While a QCA analysis cannot evaluate the presence of a Kuznets curve, in previous quantitative literature using inferential statistical methods (i.e., regression models), we found that there is no Kuznets curve for consumption-based emissions, but there is an upside-U shape relationship between affluence and production-based emissions (Pattison et al. 2014). We call this an "environmental inequality Kuznets curve", i.e., the wealthiest communities are able to displace certain types of emissions, specifically those related to energy and industrial production. In a follow-up study, Clement et al. (2017), we corroborate this finding when using a carbon footprint data set.

Still a relatively recent innovation, QCA has gained an increasing level of acceptance in various social and policy science disciplines, especially in political science, sociology, and management, and scholars have increasingly deployed the more flexible fuzzy-set variant while spurring continued refinement and interest in the QCA as a research strategy and set of techniques since the 2000s (see Rihoux et al. 2013, for a review).

The calibration and subsequent analysis was implemented with Dusa and Thiem (2014) QCA package for R.

According to Bulkely and Betsill’s meta-analysis on urban climate politics, factors such as the “intransigence” of national climate policy and a strategic turn by municipal leaders toward political approaches to making meaningful progress on sustainability-related issues, the decade beginning in 2000 represents a “second phase” of subnational government leadership on climate change and explosion of local climate policy and climate related-commitments (2013, p. 140). We have chosen to examine the decade of 2000–2010 and to help tease apart the local government characteristics that were associated with adoption, and in doing so add various forms of carbons emissions to the broader literature on this. We also note that by 2011, over 1000 mayors had already signed the U.S. Mayors Climate Protection Agreement, and the number of signatories has remained virtually unchanged since with 1060 mayoral signatories as of January 2019 (Bulkely and Betsill 2013; USMCPA 2019). Therefore, while the validity of the results beyond this period might be questioned, we are helping to better understand the potential causal relationships and adding to the understanding carbon emissions.

Slightly more permissive thresholds for CPA adoption did not substantially alter the results.

Ragin (2008) also recommends a "rule of thumb" of .85, which again is close to the consistency cutoff that we adopted. Lowering the consistency cutoff to below .80 yielded a fifth solution term covering Santa Clara and Orange Counties, both of which have high affluence, low emissions from both sources, and a low density of environmental organizations. We concentrate on the most parsimonious here to avoid over-interpreting single-cases.

It is possible to speculate that the high density of environmental organizations in Butte is related to the presence of Chico and Chico State University in an otherwise mostly rural county, whereas Sacramento is the state capital and a prominent site of advocacy.

To be clear, our calibration thresholds for assigning California counties the conditions of “Republican voting” and “affluence” are included only for comparison. These thresholds were defined on the basis of variation within California.

References

Betsill MM, Rabe BG (2009) Climate change and multilevel governance: the evolving state and local roles. In: Mazmanian D, Kraft M (eds) Towards Sustainable Communities: transition and transformations in environmental policy, 2nd edn. The MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 201–226

Brody SD, Zahran S, Grover H, Vedlitz A (2008) A spatial analysis of local climate change policy in the United States: risk, stress, and opportunity. Landsc Urban Plan 87:33–41

Bulkeley H, Betsill MM (2013) Revisiting the urban politics of climate change. Environ Polit 22(1):136–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.755797

Clement MT, Pattison A, Habans R (2017) Scaling down the ‘Netherlands fallacy’: a local-level quantitative study of the effect of affluence on the carbon footprint across the United States. Environ Sci Pol 78:1–8

Dunlap RE, Brulle RJ (eds) (2015) Climate change and society: sociological perspectives. Oxford University Press, New York

Dusa A, Thiem A (2014) Qualitative comparative analysis. R Package Version 1.1–4. URL: http://cran.r-project.org/package=QCA. Accessed 1 Aug 2018

Farrell J (2015) Corporate funding and ideological polarization about climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113(1):92–97

Farrell AE, Hanemann WM (2009) Field notes on the political economy of California climate policy. In: Selin H, VanDeveer SD (eds) Changing climates in North American politics: institutions, policymaking, and multilevel governance. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 87–110

Flyvbjerg B (2006) Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual Inq 12(2):219–245

Galli A (2015) Footprints. Oxf Bibliogr. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199363445-0046

Gurney KR, Mendoza DL, Zhou Y, Fischer ML, Miller CC, Geethakumar S, de la Rue du Can S (2009) The Vulcan Project: high resolution fossil fuel combustion CO2 emissions fluxes for the United States. Environ Sci Technol 43(14):5535–5541

Hand CM, Williams D (2019) State-level factors in metropolitan climate activism. J Publ Prof Sociol 11(1):1

Knight KW, Rosa EA, Schor JB (2013) Could working less reduce pressures on the environment? A cross-national panel analysis of OECD countries, 1970–2007. Glob Environ Chang 23(4):691–700

Kousky C, Schneider SH (2003) Global climate policy: will cities lead the way? Clim Pol 3(4):359–372

Krause RM (2011) Policy innovation, intergovernmental relations, and the adoption of climate protection initiatives by U. S cities. J Urban Aff 33(1):45–60

Lincoln YS, Guba EG (2000) The only generalization is: there is no generalization. In: Gomm R, Hammersley M, Foster P (eds) Case study method: key issues, key texts. SAGE Publications, London

Lindseth G (2004) The cities for climate protection campaign (CCPC) and the framing of local climate policy. Local Environ: Int J Justice Sustain 9(4):325–336

Logan JR, Molotch HL (1987) Urban fortunes: The political economy of place. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles

Lucas SR, Szatrowski A (2014) Qualitative comparative analysis in critical perspective. Sociol Methodol 44(1):1–79

Lutsey N, Sperling D (2008) America’s bottom-up climate change mitigation policy. Energy Policy 36(2):673–685

Martelli et al (2018) Do voters support local commitments for climate change mitigation in Italy? Ecol Econ 144:27–35

Olivier JGJ, Bouwman AF, Berdowski JJM, Veldt C, Bloos JPJ, Visschedijk AJH et al (1999) Sectoral emission inventories of greenhouse gases for 1990 on a per country basis as well as on 1× 1. Environ Sci Pol 2(3):241–263

Pattison A, Habans R, Clement MT (2014) Ecological modernization or aristocratic conservation: exploring the impact of affluence on emissions. Soc Nat Resour 27(8):850–866

Peters GP (2008) From production-based to consumption-based national emission inventories. Ecol Econ 65(1):13–23

Pitt D (2010) The impact of internal and external characteristics on the adoption of climate mitigation policies by U.S. municipalities. Environ Plann C Gov Policy 28(5):851–871

Rabe B (2004) Statehouse and greenhouse: the emerging politics of American climate change policy. Brookings Institutional Press, Washington, D.C

Rabe B (2007) Beyond Kyoto: climate change policy in multilevel governance systems. Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions 20(3):423–444

Rabe B (ed) (2010) Greenhouse governance: addressing climate change in America. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Ragin CC (1987) The comparative method: moving beyond qualitative and quantitative methods. University of California, Berkeley

Ragin CC (2000) Fuzzy-set social science. University of Chicago Press

Ragin CC (2004) Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA): state of the art and prospects. Reflections on fuzzy-set/QCA. Qual Meth Newsl Am Pol Sci Assoc Org Sec Qual Meth 2(2):3–13

Ragin CC (2008) Redesigning social inquiry: fuzzy sets and beyond. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Ramaswami A, Weible C, Main D, Heikkila T, Siddiki S, Duvall A, Pattison A, Bernard M (2012) A social-ecological-infrastructural systems framework for interdisciplinary study of sustainable city systems. J Ind Ecol 16(6):801–813

Reams MA, Clinton KW, Lam NSN (2012) Achievement of climate planning objectives among US member cities of the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI). Low Carbon Econ 3(4):137–143

Rees W, Wackernagel M (1996) Urban ecological footprints: why cities cannot be sustainable—and why they are a key to sustainability. Environ Impact Assess Rev 16(4):223–248

Rihoux B, Alamos-Concha P, Bol D, Marx A, Rezsohazy I (2013) From niche to mainstream method? A comprehensive mapping of QCA applications in journal articles from 1984 to 2011. Polit Res Q 66(1):175–184

Rudel T (2012) Defensive environmentalists and the dynamics of global reform. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Schneider CQ, Wagemann C (2010) Standards of good practice in qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and fuzzy-sets. Comp Sociol 9:1–22

Ummel K (2014) Who pollutes? A household-level database of America's greenhouse gas footprint. Center for Global Development Working Paper 381

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2013) World social science report 2013: changing global environments. UNESCO Publishing, Paris

Urpelainen J (2009) Explaining the Schwarzenegger phenomenon: local frontrunners in climate policy. Glob Environ Polit 9(3):82–105

US Conference of Mayors (2019) Climate Protection Agreement (USCMCPA). https://www.usmayors.org/mayors-climate-protection-center/. Accessed 24 Jan 2019

van den Bergh J, Grazi F (2010) On the policy relevance of ecological footprints. Environ Sci Technol 44:4843–4844

Victor D (2015) Embed the social sciences in climate policy. Nature 520:27–29

Vig NJ, Kraft ME (2010) Environmental policy: new directions for the twenty-first century, Seventh Edition. CQ Press, Washington D.C.

Wang R (2012) Leaders, followers, and laggards: adoption of the US Conference of Mayors Climate Protection Agreement in California. Environ Plann C Gov Policy 30(6):1116–1128

Wang R (2013) Adopting local climate policies: what have California cities done and why? Urban Aff Rev 49(4):593–613

Woodruff SC, Stults M (2016) Numerous strategies but limited implementation guidance in US local adaptation plans. Nat Clim Chang 6(8):796–804

World Resource Institute (2012) Greenhouse Gas Protocol. http://www.ghgprotocol.org/. Accessed 5 Jan 2016

Yin RK (2013) Case study research: design and methods. Sage publications

Zahran S, Grover H, Brody SD, Vedlitz A (2008) Risk, stress, and capacity: explaining metropolitan commitment to climate protection. Urban Aff Rev 43(4):447–474

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Habans, R., Clement, M.T. & Pattison, A. Carbon emissions and climate policy support by local governments in California: a qualitative comparative analysis at the county level. J Environ Stud Sci 9, 255–269 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-019-00544-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-019-00544-1