Abstract

This paper provides a descriptive historical analysis of the planning and writing of the Australian Curriculum: The Arts which occurred from 2009 to 2013. This process involved extensive consultation across a range of stakeholders, including curriculum research, background reading and analysis that preceded the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority’s writing process. The curriculum itself was underpinned by a range of democratic principles, including the importance of developing a socially just curriculum. This necessitated extensive discussion which interrogated the terms excellence and equity to ensure a high-quality arts education was accessible for all students, regardless of their background. The implementation of these principles is then explored through the perspective of the Drama writing team, including the importance of the subject Drama in developing a sense of inquiry and empathy in students by exploring their own and others’ stories and points of view. The final curriculum document for the Arts, and specifically for Drama exemplifies the importance of these social justice principles in responding to the Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians (2008) which advocates for equity and excellence in Australian schooling and for all young Australians to become successful learners, confident and creative individuals and active and informed citizens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Arts in the curriculum: historical and intellectual background

Down through history, the arts (and especially this author’s own, drama) have had an ambivalent, love-hate relationship with the organisers of formal education: Plato wanted the arts banned from the schools in his Republic (c.360BC, Book III); St Augustine agreed, especially about drama (Li, 2008, pp. 95–102); Saints Thomas Aquinas and More encouraged the arts (Li, 2008); Comenius recommended school as a mini-theatre of the world (Østern, 2007); Confucius and his followers acknowledged the aesthetic as one of the pillars of learning (Lin, 2015, p. 97).

But in Australia’s first compulsory schooling Act, for the State of Victoria, the arts were nowhere to be found: the curriculum consisted of ‘Reading, Writing; Arithmetic, Geography, Grammar, Drill and where possible Gymnastics, and Needlework in addition for girls’ (Government of Victoria, 1872). This was not surprising, as at that time of industrial revolution and expansion of White Australia, what the Victorian government required was a literate, compliant workforce, no more than that—though the arts flourished in private schools for the governing classes (e.g. Barcan, 1980, p. 166).

Slowly, during the twentieth century a more humanistic approach emerged, and progressive educational philosophies and then constructivism made some impact on this utilitarian minimalism. This was promoted by a century of curriculum thinkers to whom creativity, the arts and social justice have been the antithesis of that transmissive utilitarian ideal. Instead, the arts are central to the progressive ideal of education being about opening capacities, giving agency, and helping students to become capable of independent, creative and socially-minded thinking—articulated by writers like Dewey, Arnaud Reid, Vygotsky, Freire, Bruner and Eisner. And a host of art form-specific advocates, referred to in these papers. Throughout the twentieth century, the arts were edging into the house of curriculum—with visual arts and music arriving first.

By the 1990s, Governmental thinking was coming round to the significance of the arts, and the Curriculum Corporation developed a set of Statements and Profiles in the Arts (Emery & Hammond, 1994), but they were not accepted by all the States and Territories, all of which by this time had independent arts curricula, with very diverse extents to which they were mandatory—or not at all—and even different named art forms. Early in the new century, the official readiness and the deep need for a national arts curriculum became explicit. The National Statement on Education and the Arts (Ministerial Council, 2015) pledged governmental support for the arts (p. 3). Two National Reviews, one of Music Education (2005) and one of Visual Education (2008), both revealed a patchy picture with some high-quality work evident, but large deficiencies and inequities nationally both in provision and in quality.

Ready to address these findings, in 1989 the professional teacher associations for Dance, Drama, Media, Music and Visual Arts had already come together with relevant arts industry bodies to form the National Advocates for Arts Education (NAAE), in order to provide a unified voice to lobby for the arts. This had originally been in response to the National Arts in Australian Schools project, set up jointly by the state, territory and federal governments to provide a peak advocacy body of arts experts including teachers, artists and arts writers, researchers and teacher educators.

Also in 1989, the federal, state and territory governments announced the development and implementation of a common standard National Australian Curriculum, with one of its priorities being the social justice-based rationale of ensuring that children who had to move among different states—for example, Defence Forces families—were not disadvantaged by the diverse and disparate curricula operating in each. The arts were not originally to be included in the Learning Areas, but intense and effective lobbying by NAAE, and the support of the then Minister for School Education, Early Childhood and Youth, the Hon Peter Garrett, who was also lead singer of the iconic Australian band Midnight Oil, saw the arts included in the second round of subjects, with Languages and Physical Education.

The writing team, and most of our advisory committees, found that we shared those progressive and democratic arts educational ideals outlined above. As Lead Writer, I had read and built my own practice on many of those theorists, for whom both the arts and social justice are equally essential pillars of a curriculum… and so, for me, the time had come. It will be helpful to the reader to understand that philosophical congruence within the team because it underpinned the whole process. That is why this article is contextualised with my own curriculum influences, first as Lead Writer, and then as Writer for Drama.

My own awareness of the social justice implications of education grew as a young English teacher in a working-class school in a struggling UK industrial city, working off instinct, a reliance on objectives, and a vague memory of Piaget and Ralph Tyler. I signed on to a university drama course. Here I discovered drama not only as the powerful art form I wanted to teach better, but as a radical pedagogy. The timing (late 1960s) was significant. I became familiar with a quite new and different collection of curriculum and drama theorists. The collision of that reading with this novel practice gave me a completely different understanding of the power structures of schooling, and of my students. This radicalised me in social justice terms. It also destabilised my teaching for two years, while I wrestled with what democratic teaching might mean, and how that fitted in with drama. The drama literature I shall deal with later. However, these new curriculum theorists provided me with the general educational philosophy that has imbued my practice from then on, and that I brought to the National Curriculum table.

It was a time for organic curriculum rethinking. The first book my tutor cunningly gave me was a slim volume, actually written in 1939, called The Saber-toothed Curriculum (Peddiwell, 1939)—satirically written, but a profound diagnosis of the endemic inefficacy and inequity of standard curricula. Then came the blitzkrieg of books of the time slaughtering all my own sacred cows, with titles like How Children Fail (Holt, 1964), Teaching as a Subversive Activity (Postman & Weingartner, 1969), Deschooling Society (Illich, 1971), and Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Freire, 1970). All of these I read, painfully at first, then avidly. I started to realise that there was not just one curriculum, but four: what the documents prescribe; what the teachers actually teach; what the students actually learn; and most potent, the ‘hidden curriculum’ (variously attributed) which became a cult phrase for us at the time—though I have often wondered why it’s called ‘hidden’; for those with eyes to see, it is the primal curriculum that every student meets at the school gate.

Over the next decades, the revolutionary stridency of those titles moderated into a more calmly considered and scholarly re-imagining of school curriculum, starting with Pinar’s Curriculum Theorizing: The Reconceptualists (1975), and incorporating post-structuralism (Doll, 1993). These have morphed into the ongoing explorations of what constitutes ‘legitimate’ knowledge, and who decides, in a real society that acknowledges the contemporary geo-political and economic realities that children face, books like Michael Apple’s Education and Power (1982) and Democratic Schools (2007), and Nel Noddings’s The Challenge to Care in Schools: An Alternative Approach to Education (1992). Add to that a heightened understanding of how critical to all education the kind of creativity fostered by the arts is, most influentially expressed for me by Ken Robinson ‘s Out of our Minds: Learning to be Creative (2001).

So I came to the National Curriculum table with no intent that the arts were to be gratefully and quietly incorporated into the national corpus of legitimised knowledge. I wanted more than that. The visionary curriculum theorist Ted Aoki observed that the.

kind of opportunity… that makes possible deeper understanding of human acts that can transform both self and world … does not come easily to a person flowing within the mainstream. It comes more readily to one who lives at the margin… (2004, p. 56)

Now that the arts were, at last, coming in from the margins, I found my fellow Writers had the same approach to the arts being part of a transformation and re-imagining of contemporary curriculum. We each wanted our own art form to take an active, and activist, role in those ‘transformations’.

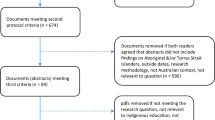

Writing the Australian curriculum (Arts)

However unified our little team of Writers was, principles of social justice cannot be imposed, nor can they flourish in an environment of inequity. The basic structure given to us by ACARA for generating and writing the curriculum was unusual: how consultative, open and democratic it was. No small coterie of appointed insiders—usually sharing traditional, mainstream beliefs and assumptions. Unfortunately, this laudable fact of the democratic process we undertook, does not appear anywhere in the published curriculum, whose credited authorship is just ‘ACARA’, which could falsely imply just such a coterie of insiders. As with many curriculum documents, this ‘official anonymity’ belies the complexity of bringing together a very wide range of informed stakeholders, and it devalues the depth and diversity of their contributions.

There were experts, certainly, numerous and openly chosen; there were official submissions, stakeholder lobby groups; several ever-present advisory groups of teachers to try out and respond to the structures as they emerged; and anyone else who wanted to was enabled to contribute their response in a 3-month online consultation on the first draft. This of course had advantages and disadvantages. Furthermore, in terms of this article, any process promoting social justice has to be itself equitable, which was a cautionary cue to our own team, because all sorts of inequity traps await within the arts themselves, and within the structures of curriculum.

ACARA’s first smart move was to appoint as initial Project Officer a fearless young education administrator with recent classroom experience and no known status-quo affiliation—in a notable pro-equity departure from the norm, not even from the ‘established art forms’ or ‘senior states’ (in fact a drama teacher from Queensland). Her task was to draw up a rudimentary draft ‘Position Paper’, as a starting point to focus the discussion during the all-important first meeting, a two-day gathering of arts experts. About 60 senior arts educators attended, wearing among them a lot more hats than that. Between them they had to represent all art forms; all age and ability levels; all states and territories; all education systems; the teachers of all those art forms and their professional associations; the teacher educators and allied academics; principals and educational administrators; and professional artists from the industry too. The one voice missing, of course, was the students themselves—as always, and inevitably.

It was an extraordinary ask, for such a disparate group to agree on anything in the arts in two days. But we did, such was the spirit of goodwill and hope; we all knew that this was a one-off opportunity for us. The meeting was imbued in general with many common philosophical standpoints, some of which we just took for granted and did not waste time in discussing. One small instance: Australian arts education across all States allows theory to grow from practice—we share the perspective that teaching the arts means teaching people in and through the arts as both artists and audience, not just about the arts or training artists (as is the tradition in many European countries, for instance).

The meeting finished with an unexpected and overwhelming majority agreement on a number of key principles that became our Mosaic commandments, and with which we worked for the next three years, facilitated by the subsequent Senior Project Officer who ably joined us from the arts industry preceded by years as a teacher in the arts. There was not consensus, of course, nor universal delight.

All of these principles, directly or indirectly, embody aspects of social equity, and so the writing team worked assiduously to honour them.

These principles were:

-

Five art forms will be represented as full ‘subjects’ within the Arts Learning Area: Dance, Drama, Media, Music and Visual Arts.

ACARA accepted this grouping with relief, as it unified the differing configuration of the arts across the states. A lively debate at the inaugural meeting about Design—claimed as a key factor by all the arts—was resolved with the acknowledgement that Design should be strongly addressed within Visual Arts, but that it should also figure in the other four art forms.

-

Those five arts will be designated alphabetically, and each have parity within the curriculum.

That caused some consternation, with some representatives of Music and Visual Arts inclined to pull rank, but with Drama, Media Arts and Dance countering that statistics were in their favour, as faster growing art forms in all States. Nevertheless, the spirit of generosity was such that finally this quite radical principle was agreed, at least in principle.

-

All children should have equal entitlement to all art forms throughout the primary years.

Our original ‘Years F-8’ demand got cut back to ‘the primary years’… but ACARA basically honoured this principle. Again, many fears were raised, some territorial, some based on doubts about teacher expertise, time and scheduling (the old chestnut of the ‘overcrowded curriculum’), and the capacity of schools to deliver on this. And again, stoutly, the meeting came together to avow that to offer children an equal opportunity and basic introduction to all the arts was an important principle. Moreover, it would actually help everybody to assert the broad significance of the arts, just as science also embodies several disciplines of equal standing, and nobody claims the primacy of chemistry over biology or vice versa.

-

In the national curriculum, the arts should remain at least as available throughout secondary education as they currently are.

We agreed that the state of the arts in secondary education was much healthier than in the primary years, with all jurisdictions having some provision of most of the arts up to senior level—though only in some states did the arts have full tertiary entrance subject status. Most states had an experienced cohort of trained secondary teachers who were teaching established and successful syllabuses, which we did not want to disrupt.

-

The five art forms are autonomous, with discrete content, learning experiences and achievement standards.

This was the other territorial battleground we fought during the meeting. Every arts teacher has had their subject traduced into service as a handmaiden for another subject—music reduced to rhythm games for maths, visual arts co-opted into painting the sets for the school musical, drama diminished into little skits for school camp, media arts turned into critical literacy text analysis, dance merely a folksy back alley in physical education, and in primary schools all of them lumped together into an amorphous form of Friday afternoon relief called Expressive Arts. Those representing the secondary sector were loud in their assault on ‘integration’, and defence of the integrity of their art form. Cookery metaphors predominated among this commentary (arts muesli, blancmange etc.) and caused considerable headaches to the curriculum writing teams, of course, as the word ‘integration’ then became taboo. All the while the writers struggled to address how we were to teach multiple arts like opera, masks, contemporary hybrid arts and more, without integrating them! To say nothing of Early Childhood teachers trying to fuse artistic play and learning, and the more progressive schools’ vision of a wholly integrated curriculum. This dilemma was partially resolved in a compromise based on the next of the meeting’s principles, as will be explained later.

-

Criteria for learning, achievement and assessment will be based on aesthetic knowledge.

This was perhaps the most productive realisation of the whole meeting, and one with which everybody could agree (though it was only partially formulated during the meeting). It needed the writers’ team to fix and clarify it and it subsequently became largely buried. The question had arisen during the integration versus autonomy debate, as to what the arts actually shared, that could be defended as a single KLA. If they are all so different, and you cannot even teach them together, why are they even in the same Learning Area? The meeting agreed that though they are all distinct forms and ‘symbolic languages’, there is a commonality and specialness about ‘the arts’ that is instantly recognised by anybody in the street. We therefore reclaimed the absolutely primal key phrase aesthetic knowledge as the common denominator of what we do. This stone tablet caused ACARA serious problems—entirely of ACARA’s own making—as I shall explain (and it is only now that it is being resolved within a new ACARA Review process (see below).

However, it proved immensely valuable to the writers of both the next two stages, the Shape Paper and the detailed Curriculum itself. We found and crafted a clear definition of aesthetic knowledge, and the curriculum is all based on that definition. All the objectives, criteria, content and learning experiences were specifically designed for aesthetic knowledge. That meant that any teacher wanting to use an art form in combination with another subject must identify content objectives and criteria from that art form as well as the base subject. Unfortunately, ACARA, owing ironically to its own social justice concerns (which insisted that every document we produced be immediately and briefly readable by a general reader), did not permit this to be fully explained, which has caused ongoing confusion and so is often ignored.

-

Scope and sequencing of learning, student progression and reporting in the arts will be planned as a two-yearly cycle, instead of the current one-year cycle used in the Phase 1 subjects (maths, English, science and history). This is because of the organic and holistic nature of arts learning, and also the five art forms’ diverse timetabling requirements. We propose Years F-2, 3-4, 5-6, 7-8, 9-10 and 11-12.

This final commandment, to our surprise readily accepted by ACARA, allowed teachers to design a flexible and child-centred progression, and also made far more practicable the programming and teaching of the arts in limited timetable allocations (see below).

The team of Lead Writers was helped by our philosophical congruence, and the fact that all of us had enough personal experience of schools and teaching to be well acquainted with those three alternative curricula (the teachers’, the students’ and the ‘hidden’). The challenges to a coherent curriculum dissipated, or we found ways round them, as we got into our prime task of realising the Shape Paper that would form the template for the detailed curriculum. Early on, we retitled ‘Media’ as Media Arts, to distinguish our aesthetic subject from those aspects of media education that really belong elsewhere, such as journalism, advertising and media technology per se. For simplicity we defined media arts as the artistic telling of stories through mediated technologies such as film, television and other electronic media.

Challenges

Two rather odd challenges were posed by ACARA—each of them a constraint imposed by the Australian demarcation of Federal versus States’ Rights. Since the curriculum was to be delivered and managed by the states and territories, they would have carriage for all the teaching and the assessment. Therefore, we were not to include any consideration of, nor reference to either! The curriculum we were developing was supposed to contain just content. Our own focus was dedicated to process, and all the arts have distinct pedagogies—in fact all the arts, especially drama and media arts, can be pedagogies in themselves. It did not make a lot of sense to ban all consideration of pedagogy. So, of course, all the way through we considered how our content would be, might be and should be taught. The result was that we were forced to bury that implicitly in our content descriptors. Nobody’s complained yet!

It was entirely liberating not having to consider assessment. That freed us from schooling’s dreaded ‘McNamara’s Law’: That you only teach what you can assess. Of course, every member of the writers’ teams was an experienced teacher, where assessment was in the genes, so there was little chance that we would come up with something un-assessable. But it was a joy to be able to leave it to the state systems to work out how.

The culinary integration versus autonomy issue we think we solved, first using the much more neutral word ‘connectivity’, and second—more important—by invoking that hard-won principle of aesthetic knowledge; i.e. if an art form is being integrated (connected) with another art form or school subject, then to be counted, the learning experiences and the assessment criteria must have content and outcomes from that art form, i.e. aesthetic ones.

Barriers and limitations

ACARA’s equity protocol that seriously hampered our own was their unbending rule that the curriculum—and every document—had to be written in Plain English: to be understood by a Year 3 primary classroom teacher, principal and parent, (and more pragmatically by a Curriculum Committee member from a non-arts background with five minutes to peruse the document before ratifying it). We needed, and pleaded constantly, unavailingly, throughout the two years of Shape Paper development, to be allowed to produce two versions of some documents. One would be for that primary teacher and Committee member; this was a useful discipline for us supposedly hi-falutin’ Writers to have to ensure that the curriculum would be comprehensible, jargon-free and implementable by any teaching professional. The second, just as crucial, would have spelled out our rationale, context and purposes in arts-specific terminology, for all the arts specialists, arts workers and scholars who needed to know what exactly we were talking about, and whether we had any kind of coherent vision or framework of knowledge; and also, how the simple statements needed in the non-specialist classroom hung together as a teachable, sophisticated Learning Area with five Subjects up to senior level.

That would that have forestalled 90% of the negative criticism that was received, particularly during the online consultation period, and prevented thousands of hours of superfluous work during that period by the nation’s arts specialists and education authorities, who wrote submissions kindly fleshing out for us our Draft Shape Paper by outlining their own coherent vision, theory and rationale. These were nearly all entirely in synch with what we would have written had we been permitted to flesh out our simplistic statements to demonstrate the sound theoretical background that underpinned and informed the Shape Paper.

This ‘dumbing down’ had other deleterious effects: not all specialist terminology is ‘jargon’. Imagine a maths syllabus where words like ‘multiplication’ and ‘algebra’ are proscribed, or a language syllabus where ‘grammar’ is forbidden. ACARA set the intelligence bar for that Year 3 teacher low. The nadir for us was reached when time after time in our drafts the phrase ‘aesthetic knowledge’ was thrown out as too difficult for that vocabulary-challenged generalist to understand. The phrase is crucial to our rationale and our structure of objectives and achievement, and a cornerstone of our solution to the difficulties encountered in matching autonomy and integration. The phrase finally was allowed a single mention in the Shape Paper, but with the definition removed. In the curriculum documents themselves, aesthetic knowledge was buried so deep that this Commandment has been until now largely unrealised in any sense.

One organising principle we wanted to embed had to be settled in a not entirely happy compromise. We wanted our curriculum organisers to emphasise the active and dynamic nature of the arts, to focus on process not product, and the recursive nature of both learning and artmaking. We particularly wanted to dismantle three traditional, sterile content binaries that we had struggled with throughout our careers.

-

The first was ‘practice versus theory’ (and the resulting quasi-philosophical arguments about the appropriate percentage of each that students should receive).

-

The second, equally unhelpful, was the ‘artist/audience’ distinction. That one could, it’s true, be of some use when dealing with performed or exhibited artistic product—films, stage productions, concerts and exhibitions. However, it’s actually misleading when dealing with art forms like jazz, process drama, dance improvisation, or any participatory art form, and betrays the recursivity of art itself.

-

Our third binary was process versus product. We unanimously all came down on the side of learning as a process—right through even to senior level.

More than that, we wanted the learning content to be expressed as active verbs—as ‘learning’ that the students do, not as ‘content’ they receive. Our cue for this was an inspired observation by drama education theorist Richard Courtney (1989). Since the word curriculum is descended from the verb currere—to run, planners of learning should ensure that teachers ‘currick’ with their students, instead of teaching ‘a curriculum’… and especially not ‘The Curriculum’. Our key organising content question became not ‘What is arts knowledge, and what skills are needed to make art’, but ‘What are people doing when they are experiencing the arts?’.

This is not by any means revolutionary within arts philosophy or pedagogy. Back in the 1960s Louis Arnaud Reid (1969) described the experience of learning art as a dynamic process, for artist and receiver, of making, apprehending sensuously and then coming to concretely comprehend. Arts education philosophers were equally action-oriented, such as Peter Abbs (1989), who identified four basic components of the artistic experience: forming, presenting, responding, transforming.

As part of my preliminary work as Lead Writer, I carried out a preliminary analysis of the arts syllabuses current in Australia (I found 49), and compared them with some notable examples world-wide. With one or two standout exceptions, most were similar—and verbal. The nomenclature varied wildly, but the majority here and particularly overseas had settled on a fairly constant set of three (3) organisers:

-

1.

Creating/forming/making/generating/conceptualising

-

2.

Presenting/performing/realising/interpreting/producing/communicating

-

3.

Responding/studying/appraising/appreciating/comprehending …

As a way of generating content descriptors and criteria, this could work fine for most performing arts, and (with a flexible interpretation of the relationship between 1. Creating and 2. Presenting) well enough for visual arts, and those spontaneous and participatory arts. That is why it is so widely adopted world-wide—in education systems from Ontario to Peru.

Having settled on this, we expected lively discussion about the words, but not a polemical battle, the only external interference we experienced during the whole four-year process. One state had a resoundingly noun-based set of organisers: ‘The artist > The artwork > The audience > The world’. For that influential State Arts Supervisor (who had invented this system), process was not more important than product, and our contradiction of their own stone tablet approach was taken to the state parliament and even to national radio. In the end, we won our verbal organisers, but reduced to two (making and responding), which was not really much better than the 50% theory/50% practice we had tried to escape. This left a major problem for all the performing arts—I will explain in terms of drama later—and made it easy for a relapse to artist/audience and ‘process/product’ binaries.

ACARA sensibly permitted the Writers’ team, and our original advisory group, to remain in a hands-on advisory capacity during the detailed writing of the curriculum, undertaken by a new group of 10 subject experts (two Writers per subject). That meant we could ensure that our Key Principles—our Mosaic Tablets—were honoured, and where they had been buried in the Shape Paper, to help the new team to retrieve and understand them. We found almost the same degree of philosophical unity among the new teams, and this proved valuable while helping them to deal with some of the equity traps in writing a practical curriculum—notably the thorny issues of relative workloads and comparable time allocations, among arts with very different dynamics and content/process/skills balances. In all cases good sense and goodwill prevailed over territorial demands.

Making it work

So, having written the curriculum, there were of course major practical factors to be addressed in implementing it. These had all been presented to us as insoluble ‘problems’. They all related to our Commandments that students should have equal entitlement to all five arts throughout the primary years. The most critical issues were the questions of time allocation, teacher expertise (or lack of it), resource provision, and external factors likely to impinge on or inhibit the implementation of the curriculum.

The first three in particular gave good ammunition, prima facie, for the only two groups to remain implacably opposed to our curriculum throughout the whole process—externally, the primary principals’ associations, and closer to home, one state teachers’ association accustomed to their art form’s pre-eminence being unchallenged. But all of the issues can to a large extent be resolved by ‘new thinking’—changing the paradigm from traditional assumptions to a different way of considering the issue… and necessary to the professional development to go with the new curriculum.

The Primary Principals were predictably concerned about squashing five art forms into the ‘overcrowded curriculum’, since there was little chance of expanded time allocations—as the states themselves had made plain. Accusatory questions flew in discussion forums: ‘Excuse me—so we will have to do 18 min of dance, drama, media arts, music and visual arts each week?’.

The myth-ridden assumption underlying that question (and the chimaera of the overcrowded curriculum) were actually quite easily addressed, but only by those capable of new-paradigm thinking—not everybody, even yet:

-

A curriculum with a scope and sequence progression over two years does not have to be thought-of in terms of lessons per week, every week; so the immediate response to the accusatory 18 minutes question should be equally robust: ‘Excuse me, do you mean you can’t find any time at all over two years (or three at the F-2 Level), for a bit of drama, dance, media, music, and visual arts - anywhere?’

-

The fact that different art forms need different time allocations (just as foreign languages and history do) should be a timetable opportunity, not a problem; learning a song or dance steps demands regular repetition over a short period; making a film or mounting a dramatic production demands intensive attention for an extended but finite period.

-

Children do not just learn one thing at a time, but lots of connected diverse knowledge simultaneously as long as it is situated, contextualised and purposeful: history with visual arts and drama; science with health education and dance. Now that does involve real integration, with imagination, not as a compromise, but as rich learning.

The Principals’ Associations also led the chorus of claims that primary teachers could not cope with the new knowledge and skills demands. When during the writing we had asked teachers themselves, showing primary focus groups drafts of our syllabus, they surprised us by mainly expressing enthusiasm and pleased anticipation that all the arts would become compulsory. They showed much more confidence in their own ability to learn adequate skills (given support and resources) than the nay-sayers. After all, though they may not have been trained for any of the arts, every adult has experienced and is surrounded by all the arts every day of their lives—it’s not like having to learn from scratch, like nuclear physics, or Napoleonic history. And there are plenty of arts-rich primary schools scattered across the country that can be used as exemplars. And, of course, there are nowadays a plethora of supporting resources—some states and education systems have already developed websites for implementing the new curriculum.

It is the same with physical resources—some are obviously a long-term proposition, like sprung floors for dance or cellos in a small country school. However, schools’ communities are proving to be treasure houses of resources and resourcefulness, inspiration, even tutelage. My own 2019 visits to one-teacher schools revealed if not variety, then plenty of basics—local composers, collections of guitars, assistance from local artists and galleries, drama festivals, art materials aplenty, often locally donated, and even in a school 50 kms from the nearest building, two three-day residencies in the same year by a visiting Brisbane artist and a ‘local’ (75 km away) dance school. As our team has maintained from the start, when it comes to implementing a socially equitable arts curriculum, where there’s a will there’s a way. The will is still sometimes the problem.

External inhibitors have not always been so soluble with imagination and goodwill. The politically-motivated Review of the Australian Curriculum (DESE, 2014) came and went for us, with ACARA managing deftly to avoid or disarm all the Reviewers’ recommendations, which would have effectively obliterated every one of our equity principles. One state, NSW, at the time of writing has still not implemented the Curriculum (not just in the arts), and a recent draft Review of their Arts Syllabus (NSW ESA, 2018) clings to the title ‘Creative Arts’, which we rejected early on, only recognises four art forms, and continues prioritising Visual Arts and Music, particularly in the secondary school. All other states and territories are implementing the Australian Curriculum, some with local variations, and with widely varied in-service and resourcing support. Western Australia has chosen to move back from our 2-Year progression model to the more restrictive 1-year model.

However, the timing of the release of our Curriculum (2013) was not kind to the arts. Besides the constant, entirely predictable state-level literacy and numeracy priorities taking teachers’ time and attention away from the arts, the otherwise admirable government and public crusade for STEM [Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths] (Education Council, 2015) has seriously distracted teachers and principals from the arts—in spite of a hopeful arts-based campaign to rename it STEAM. It seems the old cultural divide between arts and sciences still operates, as it has from well before CP Snow (1959) drew attention to it, in the sciences’ favour. This is despite cartloads of research, also for well over a century, that all spell out unequivocally the direct benefits of a broadly humane education, and each of the arts, to literacy, numeracy and all the subjects of STEM. However, that is the subject for another article with a very long reference list.

Finishing on an optimistic note, a new Review is under way, having started in 2019, and continuing at the time of writing. This time the Review is, thankfully, not driven by a hostile ideology, but a recognition that the Arts Curriculum in general works well. However, it is time to update the curriculum and also to address some over-complications and confusing terminology, which have made it difficult for general teachers to navigate, particularly in the primary years. As in the original curriculum, a wide range of key expert stakeholders has been consulted and listened to, including the NAAE. The current draft, which is open for public consultation as I write this, significantly addresses some of the problems that we failed to solve, and that I have described above. For example, aesthetic knowledge has at last been foregrounded, ‘integration’ is no longer taboo, and the Review has responded to the wishes of Early Childhood educators by designating Foundation Year as a separate Level, distinct from Years 1 and 2 and with no formal separation of the five art forms (although some activities and activity descriptors clearly identify particular art form priorities).

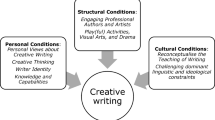

Drama in the Australian curriculum

Among those cartloads of research is the wealth of projects and statistics, over more than a century, proving that drama is a powerful aid to literacy, particularly for the disadvantaged. And as indicated earlier, drama has proved to be a powerful liberatory pedagogy. However, as I have explained, the writing team was directed not to engage with pedagogy, but leave it to the states. We did have scope to consider pedagogy, however, within ACARA’s General Capabilities, particularly literacy of course, as well as critical and creative thinking, intercultural understanding, ethical understanding and personal and social capability.

Arriving at the drama curriculum content itself was not actually so easy, especially in primary education, because of the protean nature of drama itself. Drama has been offered to teachers in schools under many guises and purposes, apart from as pedagogy. The compass includes acting classes, creative expression, speech and elocution, mime and movement, improvisation, doing plays, personal self-presentation, social learning—even therapy. ACARA’s directive to us to avoid pedagogy was actually very useful, as it shortened the list. Our order was to teach the art form. The directive did not, however, negate all the democratic concomitants of drama, which is essentially dialogical, after all.

My own most important drama curriculum influences came both from the world of education and from the world of theatre. The first prominent modern drama education scholars, the ‘curricking’ Richard Courtney (1968) and my tutor Gavin Bolton (1979), introduced me to Vygotsky, and helped me to realise that the most basic and essential dramatic act of all is dramatic play—to step into another’s shoes and pretend. In more grown-up talk, this means suspending our perception of the ‘real world’ to create an experimental model world, that has all the real world’s concrete, human and social characteristics, but is provisional, infinitely changeable, and evanescent—‘leaves not a rack behind’—as Shakespeare put it—so it can be safe to experiment in. That is drama’s special contribution to the acts of creation, expression and communication which are the essentially liberatory qualities of all the arts.

Two more of Vygotsky’s key discoveries that have proved vital to drama are his concepts of:

-

Dual affect—‘the child weeps as a patient but revels as a player’ (Vygotsky, 1933 as cited in Bolton, 1984, p. 106). This explains how the emotional, sensory and cognitive components of play combine as learning in the model world described above.

-

Zone of proximal development (ZPD). More commonly known as ‘scaffolding’, in the form developed by Jerome Bruner and his colleagues (Wood et al., 1976), this complex theory explains the phenomenon frequently observable in good drama lessons, of children and whole classes performing tasks clearly exceeding their apparent maturation levels (as determined by school measurements and expectations).

The influential drama education practitioners Dorothy Heathcote and her colleague Gavin Bolton built their theory and practice—and my understanding—largely on these principles (Bolton, 1979, 1984; Heathcote & Bolton, 1995). Their play-based learning structures dismantled the artist/audience divide, sometimes completely, in drama activities with no external audience, where, as in jazz, the participants are simultaneously creators, performers and responders.

From the theatre, by far the most influential theorist for the 60 s generation—and not least on Heathcote and Bolton—was Bertolt Brecht, who attempted to develop a socially just and educational theatre, that also started to dismantle the artist/audience divide. As much an educator as an artist, he had forthright views on the schools of his time (1940):

The young person in school is monstrously confronted by the BARBARIAN in unforgettable form. The latter possesses almost limitless power…finishing up with exhorting the student to:

…defend himself against having a whole rat’s nest of completely worthless intellectual rubbish crammed into him. (Cited in Adams, 1970, p. 1).

Dramatically, Brecht’s theory of alienation (verfremdungseffekt) has been important to the development of drama education by usefully identifying the importance, for both audiences and learners, of achieving a dynamic interplay of empathy and emotional distancing, thus tying in closely with Vygotsky’s dual affect. Brecht has more indirectly influenced another sphere of contemporary drama education, through the work of Brazilian educator Augusto Boal. Boal was inspired by Paolo Freire (and the title of his book) to develop a practice and underpinning theory he called Theatre of the Oppressed (1979)—devised for his work as a theatre director working in peasant communities, but now used world-wide in schools as much as adult communities. Though, unlike Heathcote, centred on acting and performing rather than playing, Boal’s techniques of ‘forum theatre’ with ‘spect-actors’ and ‘invisible theatre’ also cut right across the actor/audience divide.

The drama content

All the Curriculum Writers team, in line with our principles, wanted the curriculum not to be unduly prescriptive. Particularly in secondary schools and within individual education systems, there are already many imaginative drama programmes at school or system level, that are—what we could not be—context-sensitive and responsive to that community’s special opportunities and challenges.

To bring into our drama curriculum as driving forces both the creative experimentation of dramatic play, and the redefined relationship between artist and audience, we first of all had to deal with that unhelpful new binary compromise given to us of Making and Responding. With unimaginative school programmers, that could only too easily lapse into the patterns of some traditional drama syllabuses (particularly overseas), of teaching acting skills and putting on plays (making) and studying famous plays (responding). So, we joined with the other performing arts (Dance, Media Arts and Music) in subversively re-establishing the third organising dimension, where making now became again.

-

1.

Creating/forming

-

2.

Presenting/performing/producing

When we had decided what our basic, non-prescriptive content should be, we could then formulate our content descriptions to ensure that 1 and 2 were both present.

Since the field of drama is so extraordinarily diverse, our decision not to be prescriptive brought the big challenge, of deciding exactly what constituted content that all Australian students should study, and where the creative learning dimension of dramatic play should feature. However, this had been already largely solved for us 30 years earlier by our response to a bitter academic war in the United Kingdom, fought over another false binary that the warring sects created between ‘play’ and ‘dramatic art’. On a broader philosophical level, this was a manifestation of an ideological clash which occurred (and occurs) in all the arts, between ‘progressive/constructivist’ (play-based) and ‘traditional/canon-centric’ arts education. We managed to avoid this war reaching Australia’s shores by maintaining that as drama teachers we do both play and dramatic art, of course. Anybody in the street can identify some activities that they would call drama, and that would include both children playing doctors and nurses, and the Bell Shakespeare’s Hamlet. They are just at the opposite end of a long continuum from ‘play’, through ‘playmaking’, to ‘plays’, where the free forms and experimentation of play are given the shaping and controls of dramatic art. Ergo, anything so easily identifiable must be because all manifestations share the same basic elements (as in chemistry). Aristotle (c.230BCE) had already made a stab at demonstrating this. In The Art of Poetry (Chapter 7) he identified six elements. These are variously translated, but commonly Plot, Character, Thought (or Theme), Diction, Melody and Spectacle; the last two he relegated as ‘accessory elements’. Since then over the centuries many theatre scholars have expanded or modified Aristotle and reconfigured the basic elements to fit their times’ changing concepts of the nature of serious drama. Two contemporary local reconfigurations of those basic common elements for educational purposes: Time for Drama (Burgess & Gaudry, 1985) and Dramawise (Haseman & O’Toole, 1987) successfully kept the British war offshore, and became very influential over the following 30 years. Both show how those elements of drama work across all forms and genres of drama—from dramatic play and improvisation, through playmaking and scripting, to plays classic and contemporary, and their performance and production.

Since it is so serviceable, and so generally accepted by the Australian drama community, we made understanding and managing the elements of drama the central content and study organiser—and used the Play > Playmaking > Plays continuum. From this, schools and system programmers in all states and territories can devise their own context-specific and flexible drama programmes.

Equity and the drama curriculum

To conclude in key with the topic of this article, even though this author and our advisory committee made the actual decision to use these structures as our central organisers, this was a democratic decision. We were lucky that Drama Australia (DA), our teachers’ organisation, was both unified and proactive. At the start of the process, DA canvassed their members, had lengthy discussions in all states, and provided us with a clear and coherent manifesto and mandate, which we were mostly able to honour. Their submission showed that the association and its members are as committed to an equitable and democratic curriculum as the Writers.

A sentence from that original Dramawise could stand as the mission statement for this drama curriculum:

We want to give young people the tools of the trade, so that they can approach drama with the freedom and confidence of understanding—tools that artists (and teachers) often reserve to themselves… The theoretical underpinning emerges through action that is significant, not trivial. Fun, certainly, but purposeful fun. (1987, p.v)

Note

For readers interested in further reading in the development of drama curriculum in Australia, a full critical history can be found in:

O’TOOLE, J., STINSON, M. & MOORE, T. (2009). Drama and curriculum: A giant at the door. Springer.

A more detailed account of the development of this curriculum, from an artistic standpoint, can be found in:

O’TOOLE, J. (2018). The Australian curriculum: Arts—5 years old: Its conception, birth and first school report. Art Education Australia, 39(3), 427–440.

Data availability

All data is either currently available https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/the-arts/drama/ or for earlier working papers, available from either ACARA or by application to the author/

References

Abbs, P. (1989). Living powers: The arts in education. Falmer Press.

Adams, A. (1970). Team teaching and the teaching of English. Elsevier.

Aoki, Ted. (2004). A Lingering Note. In William Pinar & Rita Irwin (Eds.), Curriculum in a new key: The collected works of Ted T. Aoki (pp. 1–88). Routledge.

Apple, M. (1982). Education and power. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Apple, M. (2007). Democratic schools (2nd ed.). Heinemann.

Aristotle (c230BCE). The poetics. Variously translated and published.

Barcan, A. (1980). A history of Australian education. OUP.

Boal, A. (1979). Theatre of the Oppressed. Pluto Press.

Bolton, G. (1979). Towards a theory of drama in education. Longmans.

Bolton, G. (1984). Drama as education. Longmans.

Burgess, R., & Gaudry, P. (1985). Time for drama: A handbook for secondary teachers. Longman Cheshire.

Education Council. (2015). National STEM school education strategy. Retrieved 20 June 2020 from http://www.educationcouncil.edu.au/site/DefaultSite/filesystem/documents/National%20STEM%20School%20Education%20Strategy.pdf

Courtney, R. (1968). Play, drama and thought. Cassell.

Davis, D. (2008). First we see: The national review of visual arts education. Australia Council for the Arts.

Department of Education, Skills and Employment. (2014). Review of the Australian curriculum. Retrieved 12 June 2020 from https://docs.education.gov.au/documents/review-australian-curriculum-final-report

Doll, W. (1993). A postmodern perspective on curriculum. Teachers’ College Press.

Emery, L. & Hammond, G. (1994). A statement on the arts for Australian schools. Curriculum Corporation.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy and the oppressed. Herder & Herder.

Government of Victoria. (1872). The education act. Appendix. Victorian Government.

Haseman, B., & O’Toole, J. (1987). Dramawise: An introduction to the elements of drama. Heinemann.

Heathcote, D., & Bolton, G. (1995). Drama for learning: Dorothy Heathcote’s mantle of the expert approach to education. Pearson.

Holt, M. (1964). How children fail. Pitman.

Illich, I. (1971). Deschooling society. Harper & Row.

Li, C.C. (2008). Brecht’s epic theatre in drama education. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Australian National University.

Lin, M. C. (2015). The Ideology of Confucianism concerning arts education. In M. Fleming, L. Bresler, & J. O’Toole (Eds.), Routledge International Handbook of the Arts and Education (pp. 96–97). Routledge.

Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs. (2008). The Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young Australians. Curriculum Corporation.

New South Wales Standards Authority. (December 2018). Creative Arts K-6 draft syllabus. New South Wales Standards Authority.

Noddings, N. (1992). The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education. Teachers’ College Press.

Østern, A.L. (2007). The future of arts education – a European perspective. Journal of Artistic and Creative Education, Melbourne, 1(i). Unpaged.

Pascoe, R., Leong, S., MacCallum, J., Mackinlay, E., Marsh, K., Smith, B., Church, T., & Winterton, A. (2005). Augmenting the diminished: The national review of school music education. Science and Training/ Murdoch University.

Peddiwell, J. Abner. (1939). Saber-tooth curriculum, including other lectures in the history of paleolithic education. McGraw-Hill.

Pinar, W. (1975). Curriculum theorizing: The reconceptualists. Educators International Press.

Plato. (c.360BCE). The Republic: Book III. Variously published.

Postman, N., & Weingartner, C. (1969). Teaching as a subversive activity. Delacorte Press.

Reid, L. A. (1969). Meaning in the Arts. Allen & Unwin.

Robinson, Ken. (2001). Out of our minds: Learning to be creative. Wiley.

Snow, C. P. (1959). The two cultures and the scientific revolution. Cambridge University Press.

Wood, D. J., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem-solving skills. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89–100.

Funding

For original data collection, ACARA 2009–2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Toole, J. The basic principles of a socially just arts curriculum, and the place of drama. Aust. Educ. Res. 48, 819–836 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00480-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00480-6