Abstract

Vestibular neuritis was first reported in 1952 by Dix and Hallpike, and 30% of patients reporting a flu-like symptom before acquiring the disorder. The most common causes are viral infections, often resulting from systemic viral infections or bacterial labyrinthitis. Here we presented a rare case of acute vestibular neuritis after the adenoviral vector-based COVID-19 vaccination. A 51-year-old male pilot awoke early in the morning with severe vertigo, nausea, and vomiting after receiving the first dose of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine 11 days ago. Nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test and chest CT scan were inconclusive for COVID-19 pneumonia. Significant findings were a severe spontaneous and constant true-whirling vertigo which worsened with head movement, horizontal-torsional spontaneous nystagmus, abnormal caloric test, positive bedside head impulse tests, and inability to tolerate head-thrust test. PTA, MRI of the brain and internal auditory canal, and cerebral CT arteriography were normal. According to the clinical, imaging, and laboratory findings, he was admitted to the neurology ward and received treatment for vestibular neuritis. His vertigo increased gradually over 6–8 h, peaking on the first day, and gradually subsided over 7 days. Ten days later, the symptoms became tolerable; the patient was discharged with advice for home-based vestibular rehabilitation exercises. Despite the proper treatment and rehabilitation, signs of dynamic vestibular imbalances persisted after 1 year. Based on the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations, the Air Medical Council (AMC) suspended him from flight duties until receiving full recovery. Several cases of vestibular neuritis have been reported in the COVID-19 patients and after the COVID-19 vaccination. This is the first case report of acute vestibular neuritis after the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination in a healthy pilot without past medical history. However, the authors believe that this is a primary clinical suspicion that must be considered and confirmed after complete investigations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vestibular neuritis was first reported in 1952 by Dix and Hallpike with an incidence of 3.5 per 100,000 persons. Many terms have been used to describe this constellation of symptoms, including acute viral labyrinthitis, vestibular neuronitis, vestibuloneuropathy, and epidemic vertigo. The typical onset age is between the fourth and seventh decades of life, with 30% of individuals reporting a flu-like symptom before acquiring the disorder. Vestibular neuritis most commonly affects the superior labyrinth and is a diagnosis of exclusion. The most common causes are viral infections, often resulting from a systemic virus such as influenza or the herpes viruses (which cause chickenpox, shingles, and cold sores). Bacterial forms are rare and can result from an untreated middle ear infection or meningitis. This self-limited disorder recovers completely in most patients, but the recurrent episodes may appear in up to 11% of patients. Spontaneous vertigo, nausea, vomiting, and unsteady gait can range from mild to severe and can occur chronically. Perilymph fistula, labyrinthitis (with hearing loss), benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, Meniere’s disease, vertebral artery dissection, intracranial hemorrhage, hydrocephalus, tumor, and infection are the most common differential diagnosis. Comorbidities include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and hypothyroidism. Treatment focuses on symptom relief, inflammation reduction with the use of steroids, and vestibular rehabilitation exercise. Antiemetics, antihistamines, anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, and corticosteroids (controversial) are used for treatment. Vestibular rehabilitation exercises are effective in reducing the duration of symptoms and improving gaze stability and vestibulospinal compensation; a home-based or formal rehabilitation program should be prescribed after the acute symptoms have subsided (Bae et al. 2022; Jeong et al. 2013).

Here we presented a rare case of acute vestibular neuritis (aVN) after the adenoviral vector-based COVID-19 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) vaccination in a healthy pilot.

Case report

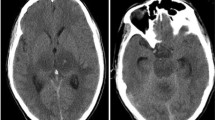

A 51-year-old Caucasian male airbus A300-600 pilot awoke early in the morning with spontaneous severe vertigo, nausea, and vomiting. Upon standing, he had a mild truncal deviation to the left with some difficulty maintaining balance. In the emergency ward, he denied other symptoms, tobacco or medication use, or significant other past medical histories except that he received the first dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca) vaccine 11 days ago. His vital signs included an oral temperature of 37.2 °C, blood pressure of 125/75 mmHg, heart rate of 82 beats/min, respiratory rate of 15 breaths/min, and blood oxygen saturation of 98% in room air. Nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test and chest CT scan were inconclusive for COVID-19 pneumonia. Significant findings on examination were a severe spontaneous and constant true-whirling vertigo which was worsening with head movement, horizontal-torsional spontaneous nystagmus that was beating away from the left side, the horizontal nystagmus which increased during gaze in the direction of the quick phases and decreased when looking in the opposite direction, the ocular tilt reaction that comprised head tilt, ocular torsion, and deviation, abnormal canal paresis bithermal caloric test, bedside head impulse tests with corrective saccades after a head impulse in the left direction, and the inability to tolerate head-thrust test. However, pure-tone audiometry (PTA), MRI of the brain and internal auditory canal (with and without contrast), and cerebral CT arteriography were normal (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

MRI of the brain and internal auditory canal (with and without contrast). A Coronal T1, B axial T2-Space IAM, C axial DWI, and D axial FLAIR. The cerebellopontine angles are normal. No mass lesion identified. The internal auditory canals, seventh and eighth cranial nerves, and the internal ear structures are unremarkable. No restricted diffusion. Incidental left posterior temporal lobe developmental venous angioma. There is a sebaceous cyst in the left parietal scalp. Remainder of the study is normal

The significant laboratory assessment results are presented in Table 1.

Findings ruled out all possible causes (such as perilymph fistula, labyrinthitis, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, Meniere’s disease, vertebral artery dissection, intracranial hemorrhage, hydrocephalus, tumor, or infection) and indicated aVN as the final diagnosis. The patient was admitted to the neurology ward and received routine treatment (Table 2). He preferred to be in the right lateral decubitus position with closed eyes. His vertigo increased gradually over 6–8 h, peaking on the first day, and gradually subsided over 7 days. Ten days later, the symptoms became tolerable, the horizontal-torsional spontaneous nystagmus was toward the left, and the brain MRI was normal (Fig. 4).

The patient was discharged and recommended for home-based vestibular rehabilitation exercises (Table 2).

Despite the proper treatment and continuous rehabilitation, his symptoms and signs of static vestibular imbalances (such as spontaneous nystagmus, ocular torsion, and ipsilesional subjective visual vertical tilt) improved completely within 13 weeks, while his signs of dynamic vestibular imbalances (such as corrective saccades of head impulse test, head-shaking nystagmus, vibration-induced nystagmus, and caloric paresis) persisted after 1 year. Based on the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations (title-14/chapter-I/subchapter-D/part-67/subpart-B/section-67.105), the Air Medical Council (AMC) suspended him from flight duties until complete recovery.

Discussion

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a new human pathogen caused by a family of RNA coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), which include different variants and specific characterizations. In an unprecedented public health emergency in recent human history, the healthcare systems have been plagued by a rapidly transmitted virus with no specific treatment. COVID-19 mostly affects the respiratory system, ranging from mild flu-like symptoms to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). In a subset of patients with yet unknown causes, COVID-19 has a particularly stormy course characterized by inflammatory cytokine response (storm) and multi-organ failure (MOF) and may be potentially fatal. Extra respiratory multi-systemic complications such as neurologic, hematologic, cardiovascular, renal, liver, musculoskeletal, dermatologic, psychological, gastrointestinal, and vestibular have all been reported in the medical literature. Several cases of vestibular neuritis have been reported in these patients since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The mechanisms leading to these complications are increasingly being studied. However, there is a paucity of data about the disease course once the patient has had clinical and/or microbiological recovery (Shahali et al. 2021; Darvishi and Shahali 2021; Giannantonio et al. 2021; Mat et al. 2021; Oldenburg et al. 2021).

World global efforts to control the COVID-19 pandemic are based on preventive protocols, health surveillance, and vaccine production, especially for high-risk individuals. Any immunization method (especially vaccination) has specific complications due to stimulation of the immune system and immune product formation. Despite passing at least 3 stages of clinical trials, new vaccines can have dangerous side effects and may be detected many years later. Currently, four types of COVID-19 vaccines are innovated: (1) the DNA-based vaccines (introduce the DNA coding for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein into cells using viral vectors, inducing cells to produce spike proteins), (2) the mRNA vaccines (similarly introduce mRNA into cells, usually via a lipid nanoparticle), (3) the protein-based vaccines (are based on the spike protein or its fragments), and (4) the inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virus (Goss et al. 2021).

The safe implementation of vaccines is of major importance, and now many cases of unusual events, especially following the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccines, have been reported. Concern about neurological complications from COVID-19 vaccines escalated in the fall of 2020 when many cases of transverse myelitis and Guillain-Barré syndrome were mainly reported 4 to 16 days after receiving the first dose of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine (Das et al. 2019; Blauenfeldt et al. 2021). Thereafter, many European countries (such as Austria, Norway, and Denmark) reported unusual events in the healthy persons following vaccination with the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccines. This led to stopping the use of these vaccines temporarily or permanently in many countries. These days, different possible side effects of the COVID-19 vaccines are under close investigation, and many cases were reported in the literature yet (Goss et al. 2021; Blauenfeldt et al. 2021; Schultz 2021). Many cases of vestibular neuritis were presented after COVID-19 vaccination too (Jeong 2021; Bramer et al. 2022). However, this was the first case of vestibular neuritis after COVID-19 vaccination in a pilot.

According to the civil aviation medical authorities, the pilots with acute vestibular neuritis must be suspended from flying duties, evaluated, and treated by an otolaryngologist or neurologist who agreed with the diagnosis. They must be grounded during treatment due to their symptoms and medication side effects which may be an important hazard for flight safety. After the resolution of symptoms and a satisfactory report from the aeromedical examiner, the pilot may become eligible for the waiver and return to flying with 1 year of operational multi-pilot limitation (OML). Then, if there is no symptom of recurrence, he can fly without restriction (Gradwell and Rainford 2016; Giovanetti 2021).

Conclusions

The health and medical fitness of the pilots is necessary for aviation safety. The new vaccine products produced with emergency authorization may have many side effects and may present a long time later. Acute vestibular neuritis in a middle-age healthy and physically fit male pilot with no medical history (except for receiving the first dose of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca) vaccine 11 days ago) and presentations of several cases of acute vestibular neuritis following the COVID-19 pneumonia or COVID-19 vaccines in literature indicated that the AstraZeneca vaccine may be the main cause for abnormal immune responses and acute vestibular neuritis in our case. (10–13) However, the authors believe that this is a primary clinical suspicion that must be considered and confirmed after complete investigations.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

RNA coronavirus

- ChAdOx1 nCoV-19:

-

Adenoviral vector-based COVID-19

- PTA:

-

Pure-tone audiometry

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- aVN:

-

Acute vestibular neuritis

- SARS:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- MOF:

-

Multi-organ failure

- AME:

-

Aeromedical examiner

- OML:

-

Operational multi-pilot limitation

References

Bae CH, Na HG, Choi YS (2022) Current diagnosis and treatment of vestibular neuritis: a narrative review. J Yeungnam Med Sci 39(2):81–88. https://doi.org/10.12701/yujm.2021.01228

Blauenfeldt RA, Kristensen SR, Ernstsen SL, Kristensen CCH, Simonsen CZ, Hvas AM (2021) Thrombocytopenia with acute ischemic stroke and bleeding in a patient newly vaccinated with an adenoviral vector-based COVID-19 vaccine. J Thromb Haemost 19(7):1771–1775. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.15347

Bramer S, Jaffe Y, Sivagnanaratnam A (2022) Vestibular neuronitis after COVID-19 vaccination. BMJ Case Rep 15(6):e247234. Published 2022 Jun 6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2021-247234

Darvishi M, Shahali H (2021) Overt hematochezia: A rare gastrointestinal presentation in patients with corona virus disease 2019. Med J Armed Forces India 77(2):494–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mjafi.2021.04.004

Das AS, Regenhardt RW, Feske SK, Gurol ME (2019) Treatment approaches to lacunar stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 28(8):2055–2078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.05.004

Giannantonio S, Scorpecci A, Montemurri B et al (2021) Case of COVID-19-induced vestibular neuritis in a child. BMJ Case Rep 14(6):e242978. Published 2021 Jun 1. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2021-242978

Giovanetti PM (2021) Policy memo regarding aviation medical examiner (AME) evaluations of airmen and air traffic control specialists (ATCS) with a history of COVID-19 [Internet]. Washington, DC: Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Available from: https://www.faa.gov/licenses_certificates/medical_certification/media/COVID-19AMEEvaluationPolicy.pdf. Accessed Mar 2021

Goss AL, Samudralwar RD, Das RR, Nath A (2021) ANA investigates: neurological complications of COVID-19 vaccines. Ann Neurol 89(5):856–857. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.26065

Gradwell DP, Rainford DJ (2016) Enesting’s aviation and space medicine. 5th ed. London: CRC Press

Jeong J (2021) Vestibular neuritis after COVID-19 vaccination. Hum VaccinImmunother 17(12):5126–5128. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.2013085

Jeong SH, Kim HJ, Kim JS (2013) Vestibular neuritis. Semin Neurol 33(3):185–194

Mat Q, Noël A, Loiselet L et al (2021) Vestibular neuritis as clinical presentation of COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2021 Feb 11]. Ear Nose Throat J. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145561321995021

Oldenburg J, Klamroth R, Langer F, Albisetti M, von Auer C, Ay C, Korte W, Scharf RE, Pötzsch B, Greinacher A (2021) Diagnosis and Management of Vaccine-Related Thrombosis following AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccination: Guidance Statement from the GTH. Hamostaseologie 41(3):184–189. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1469-7481. Epub 2021 Apr 1. Erratum in: Hamostaseologie. 2021 May 12; PMID: 33822348

Schultz NH, Sørvoll IH, Michelsen AE et al (2021) Thrombosis and thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination. N Engl J Med 384(22):2124–2130. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2104882

Shahali H, Ghasemi A, Farahani RH, Nezami Asl A, Hazrati E (2021) Acute transverse myelitis after SARS-CoV-2 infection: a rare complicated case of rapid onset paraplegia. J Neurovirol 27(2):354–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-021-00957-1

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shahali, H., Hamidi Farahani, R., Hazrati, P. et al. Acute vestibular neuritis: A rare complication after the adenoviral vector-based COVID-19 vaccine. J. Neurovirol. 28, 609–615 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-022-01087-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-022-01087-y