Abstract

Background and Objective

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C9 catalyzes the biotransformation of indomethacin to its inactive metabolite O-desmethylindomethacin (DMI). The aim of this work was to determine the effect of CYP2C9 polymorphisms on indomethacin metabolism in pregnant women.

Methods

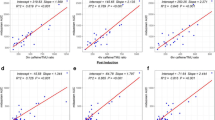

Plasma concentrations of indomethacin and DMI at steady state were analyzed with a validated LC–MS/MS method. DNA was isolated from subject blood and buccal smear samples. Subjects were grouped by genotype for comparisons of pharmacokinetic parameters.

Results

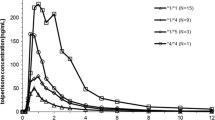

For subjects with the *1/*2 genotype, the mean steady-state apparent oral clearance (CL/Fss) of indomethacin was 13.5 ± 7.7 L/h (n = 4) and the mean metabolic ratio (AUCDMI/AUCindomethacin) was 0.291 ± 0.133. For subjects with the *1/*1 genotype, these values were 12.4 ± 2.7 L/h and 0.221 ± 0.078, respectively (n = 14). Of note, we identified one subject who was a carrier of both the *3 and *4 alleles, resulting in an amino acid change (I359P) which has not been reported previously. This subject had a metabolic ratio of 0.390 and a CL/Fss of indomethacin (24.3 L/h) that was nearly double the wild-type clearance.

Conclusion

Although our results are limited by sample size and are not statistically significant, these data suggest that certain genetic polymorphisms of CYP2C9 may lead to an increased metabolic ratio and an increase in the clearance of indomethacin. More data are needed to assess the impact of CYP2C9 genotype on the effectiveness of indomethacin as a tocolytic agent.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Goldenberg R. The management of preterm labor*1. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(5):1020–37.

Bivins HA, Newman RB, Fyfe DA, Campbell BA, Stramm SL. Randomized trial of oral indomethacin and terbutaline sulfate for the long-term suppression of preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(4):1065–70.

Vermillion ST, Scardo JA, Lashus AG, Wiles HB. The effect of indomethacin tocolysis on fetal ductus arteriosus constriction with advancing gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(2):256–961.

Rytting E, Nanovskaya TN, Wang X, Vernikovskaya DI, Clark SM, Cochran M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of indomethacin in pregnancy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53(6):545–51.

Anderson GD. Pregnancy-induced changes in pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44(10):989–1008.

Alqahtani S, Kaddoumi A. Development of physiologically based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model for indomethacin disposition in pregnancy. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):0139762.

Isoherranen N, Thummel KE. Drug metabolism and transport during pregnancy: how does drug disposition change during pregnancy and what are the mechanisms that cause such changes? Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41(2):256–62.

Wyatt JE, Pettit WL, Harirforoosh S. Pharmacogenetics of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Pharmacogenomics J. 2012;12(6):462–7.

Aithal GP, Day CP, Kesteven PJ, Daly AK. Association of polymorphisms in the cytochrome P450 CYP2C9 with warfarin dose requirement and risk of bleeding complications. Lancet. 1999;353(9154):717–9.

Ke AB, Nallani SC, Zhao P, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Unadkat JD. Expansion of a PBPK model to predict disposition in pregnant women of drugs cleared via multiple CYP enzymes, including CYP2B6, CYP2C9 and CYP2C19. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(3):554–70.

Martin JH, Begg EJ, Kennedy MA, Roberts R, Barclay ML. Is cytochrome P450 2C9 genotype associated with NSAID gastric ulceration? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;51(6):627–30.

Xu WJ, Zhang S, Yang Y, Zhang N, Wang W, Liu SY, et al. Efficient inhibition of human colorectal carcinoma growth by RNA interference targeting polo-like kinase 1 in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2011;26(4):427–36.

Jaja C, Patel N, Scott SA, Gibson R, Kutlar A. CYP2C9 allelic variants and frequencies in a pediatric sickle cell disease cohort: implications for NSAIDs pharmacotherapy. Clin Transl Sci. 2014;7(5):396–401.

Smith CJ, Ryckman KK, Bahr TM, Dagle JM. Polymorphisms in CYP2C9 are associated with response to indomethacin among neonates with patent ductus arteriosus. Pediatr Res. 2017;82:776.

Jeong H. Altered drug metabolism during pregnancy: hormonal regulation of drugmetabolizing enzymes. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2010;6(6):689–99.

Quinney SK, Patil AS, Flockhart DA. Is personalized medicine achievable in obstetrics? Semin Perinatol. 2014;38(8):534–40.

https://www.pharmvar.org/gene/CYP2C9. Accessed 7 Feb 2018.

Xie H-G, Prasad HC, Kim RB, Stein CM. CYP2C9 allelic variants: ethnic distribution and functional significance. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54(10):1257–70.

Dean L. Warfarin therapy and the genotypes CYP2C9 and VKORC1: medical genetics summaries. Bethesda: National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012.

Dean L. Celecoxib therapy and CYP2C9 genotype: medical genetics summaries. Bethesda: National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012.

Maekawa K, Adachi M, Matsuzawa Y, Zhang Q, Kuroki R, Saito Y, et al. Structural basis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in cytochrome P450 2C9. Biochemistry. 2017;56(41):5476–80.

Niinuma Y, Saito T, Takahashi M, Tsukada C, Ito M, Hirasawa N, et al. Functional characterization of 32 CYP2C9 allelic variants. Pharmacogenomics J. 2014;14(2):107–14.

Rodrigues AD. Impact of CYP2C9 genotype on pharmacokinetics: are all cyclooxygenase inhibitors the same? Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33(11):1567–75.

Tracy TS, Hutzler JM, Haining RL, Rettie AE, Hummel MA, Dickmann LJ. Polymorphic variants (CYP2C9*3 and CYP2C9*5) and the F114L active site mutation of CYP2C9: effect on atypical kinetic metabolism profiles. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30(4):385–90.

Imai J, Ieiri I, Mamiya K, Miyahara S, Furuumi H, Nanba E, et al. Polymorphism of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C9 gene in Japanese epileptic patients: genetic analysis of the CYP2C9 locus. Pharmacogenetics. 2000;10(1):85–9.

Scott SA, Jaremko M, Lubitz SA, Kornreich R, Halperin JL, Desnick RJ. CYP2C9*8 is prevalent among African-Americans: implications for pharmacogenetic dosing. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10(8):1243–55.

Choi S-Y, Koh KH, Jeong H. Isoform-specific regulation of cytochromes P450 expression by estradiol and progesterone. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41(2):263–9.

Henderson BE, Bernstein L, Ross RK, Depue RH, Judd HL. The early in utero oestrogen and testosterone environment of blacks and whites: potential effects on male offspring. Br J Cancer. 1988;57(2):216–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The authors are grateful for research support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U10HD04789108 and R01HD083003).

Conflict of interest

Authors Mansi Shah, Meixiang Xu, Poonam Shah, Xiaoming Wang, Shannon M. Clark, Maged Costantine, Holly A. West, Tatiana N. Nanovskaya, Mahmoud S. Ahmed, Sherif Z. Abdel-Rahman, Raman Venkataramanan, Steve N. Caritis, Gary D.V. Hankins, and Erik Rytting declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its actual amended version, the International Conference on Harmonization-Good Clinical Practices (ICH-GCP) guidelines.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, M., Xu, M., Shah, P. et al. Effect of CYP2C9 Polymorphisms on the Pharmacokinetics of Indomethacin During Pregnancy. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 44, 83–89 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13318-018-0505-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13318-018-0505-7