Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the non-inferiority of a lower therapeutic dose (300,000 IU) in comparison to standard dose (600,000) IU of Vitamin D for increasing serum 25(OH) D levels and achieving radiological recovery in nutritional rickets.

Design

Randomized, open-labeled, controlled trial.

Setting

Tertiary care hospital.

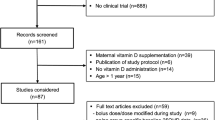

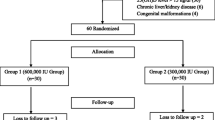

Participants

76 children (median age 12 mo) with clinical and radiologically confirmed rickets.

Intervention

Oral vitamin D3 as 300,000 IU (Group 1; n=38) or 600,000 IU (Group 2; n=38) in a single day.

Outcome variables

Primary: Serum 25(OH)D, 12 weeks after administration of vitamin D3; Secondary: Radiological healing and serum parathormone at 12 weeks; and clinical and biochemical adverse effects.

Results

Serum 25(OH)D levels [geometric mean (95% CI)] increased significantly from baseline to 12 weeks after therapy in both the groups [Group 1: 7.58 (5.50–10.44) to 16.06 (12.71–20.29) ng/mL, P<0.001]; Group 2: 6.57 (4.66–9.25) to 17.60 (13.71–22.60, P<0.001]. The adjusted ratio of geometric mean serum 25(OH)D levels at 12 weeks between the groups (taking baseline value as co-variate) was 0.91 (95% CI: 0.65–1.29). Radiological healing occurred in all children by 12 weeks. Both groups demonstrated significant (P<0.05) and comparable fall in the serum parathormone and alkaline phosphatase levels at 12 weeks. Relative change [ratio of geometric mean (95% CI)] in serum PTH and alkaline phosphatase, 12 weeks after therapy, were 0.98 (0.7–1.47) and 0.92 (0.72–1.19), respectively. The serum 25(OH)D levels were deficient (<20 ng/mL) in 63% (38/60) children after 12 weeks of intervention [Group 1: 20/32 (62.5%); Group 2: 18/28 (64.3%)]. No major clinical adverse effects were noticed in any of the children. Hypercalcemia was documented in 2 children at 4 weeks (1 in each Group) and 3 children at 12 weeks (1 in Group 1 and 2 in Group 2). None of the participants had hypercalciuria or hypervitaminosis D.

Conclusion

A dose of 300,000 IU of vitamin D3 is comparable to 600,000 IU, administered orally, over a single day, for treating rickets in under-five children although there is an unacceptably high risk of hypercalcemia in both groups. None of the regime is effective in normalization of vitamin D status in majority of patients, 3 months after administering the therapeutic dose.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Seth A, Marwaha RK, Singla B, Aneja S, Mehrotra P, Sastry A, et al. Vitamin D nutritional status of exclusively breast fed infants and their mothers. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2009;22:241–246.

Balasubramanian S, Ganesh R. Vitamin D deficiency in exclusively breast-fed infants. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127:250–255.

Marwaha RK, Sripathy G. Vitamin D and bone mineral density of healthy school children in northern India. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127:239–244.

Mishra M, Pacaud D, Petryk A, Solberg PF, Kappy M. Vitamin D deficiency in children and its management: review of current knowledge and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2008;122:398–417.

Muuns C, Zacharin MR, Rodda CP, Batch JA, Morley R, Cranswick NE, et al. Prevention and treatment of infant and childhood vitamin D in Australia and New Zealand: A consensus statement. Med J Aust. 2006;185:268–272.

Davies JH, Shaws NZ. Preventable but no strategy: vitamin D deficiency in the UK. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:614–615.

Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911–1930.

Gupta P, Shah D, Ghai OP. Micronutrients in health and disease. In: Ghai OP, Gupta P, Paul VK (editors). Essential Pediatrics, 6th ed. New Delhi: CBS; 2004. P. 129.

Ozkan B, Buyukavcï M, Energin M. Nutritional rickets: comparison of three different therapeutic approach 300,000 U p.o., 300,000 IU i.m. and 600,000 IU p.o. Cocuk Sagöligöive Hastaliklari Dergisi. 2000;43:30–35.

Billoo AG, Murtaza G, Memon MA, Khaskheli SA, Iqbal K, Rao MH. Comparison of oral versus injectable vitamin D for the treatment of nutritional vitamin D deficiency rickets. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2009;19:428–431.

Voloc A, Esterle L, Nguyen TM, Debray OW, Colofitchi A, Jehan F, et al. High prevalence of genu varum/valgum in European children with low vitamin D status and insufficient dairy products/calcium intakes: Clinical study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;163:811–817.

Cesur Y, Caksen H, Gundem A. Comparison of low and high dose of vitamin D treatment in nutritional vitamin D deficiency rickets. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2003;16:1105–1109.

Arabi A, Rassi RE, Fuleihan GE. Hypovitaminosis D in developing countries — prevalance, risk factors and outcomes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6:550–561.

Shah D, Gupta P. Nutrition and health. In: Gupta P, editor. Textbook of Pediatrics. New Delhi: CBS Publishers and Distributors; 2013.p. 51–82.

WHO. Physical status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. Report of WHO Expert Committee. Geneva: WHO; 1987.

World Health Organization. The WHO Child Growth Standards. Available from: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en/. Accessed on September 11, 2012.

WHO Anthro for Personal Computers, Version 3.2.2, 2011: Software for Assessing Growth and Development of the World’s Children. Geneva: WHO, 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/software/en/. Accessed on September 11, 2012.

Merill V. Atlas of Roentgenographic Positions and Standard Radiologic Procedures. Fourth Edition. USA: Mosby; 1975. p. 38 and 92.

Nicholson JF, Pesce MA. Reference ranges for laboratory tests and procedures. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 17th edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003. p. 2396–2427.

Thacher TD, Fischer PR, Pettifor JM, Lawson JO, Manaster BJ, Reading JC. Radiographic scoring method for the assessment of the severity of nutritional rickets. J Trop Pediatr. 2000;46:132–139.

Holick MF. The role of vitamin D for bone health and fracture prevention. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2006;4:96–102.

Soliman AT, Dabbagh M, Adel A, Ali MA, Bedair EM, Alaily RK. Clinical responses to a mega-dose of vitamin D3 in infants and toddlers with vitamin D deficiency rickets. J Trop Pediatr. 2010;56:19–26.

Awumey EM, Mitra DA, Hollis BW. Vitamin D metabolism is altered in Asian Indians in the southern United States: a clinical research study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:169–173.

Vupputuri MR, Goswami R, Gupta N, Ray D, Tandon N, Kumar N. Prevalence and functional significance of 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency and vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms in Asian Indians. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1411–1419.

Garg MK, Marwaha RK, Khadgawat R, Ramot R, Oberoi AK, Mehan N, et al. Efficacy of vitamin D loading doses on serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels in school going adolescents: an open label non-randomized prospective trial. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2013;26:515–523.

Khadgawat R, Marwaha RK, Garg MK, Ramot R, Oberoi AK Sreenivas V, et al. Impact of vitamin D fortified milk supplementation on vitamin D status of healthy school children aged 10-14 years. Osteoporos Int. 2013;2:2335–2343.

Sahay M, Sahay R. Rickets-vitamin D deficiency and dependency. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:164–176.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mittal, H., Rai, S., Shah, D. et al. 300,000 IU or 600,000 IU of oral vitamin D3 for treatment of nutritional rickets: A randomized controlled trial . Indian Pediatr 51, 265–272 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-014-0399-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-014-0399-7