Abstract

The aim of this study was to model and optimize the adsorption of Pb(II) ions from an aqueous solution using Africa elemi seed, mucuna shell and oyster shell modified with orthophosphorous acid used as adsorbents. The influence of operational parameters such as adsorbent dosage, initial pH and contact time was evaluated by response surface methodology (RSM). The interactions between the operational parameters were evaluated using Box–Behnken design of response surface methodology. The optimum conditions for maximum removal of Pb(II) ions were observed at pH of 2.0, 100 mg adsorbent dosage and 70 min of contact time, with correlation coefficient R2, 0.996 for Africa elemi seed adsorbent; pH of 6.0, 100 mg adsorbent dosage and 40 min contact time with R2 0.996 for mucuna shell adsorbent; and pH of 6.0, 100 mg adsorbent dosage and contact time of 40 min for oyster shell adsorbent. The ANOVA results obtained from the RSM were analyzed using second-order polynomial equations, and the contour plots showed the interaction among the variables of the adsorption. This shows that the prepared low-cost adsorbents can be effectively adopted for the removal of Pb(II) ions from industrial wastewaters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An increase in population has resulted in rapid increase in industrialization, which creates room for more generation of effluent and domestic wastewaters into the aquatic ecosystem (Adewuyi and Pereira 2017; Azari et al. 2017; Aguilar et al. 2019). These wastewaters contains heavy metals such as cadmium, zinc, lead, chromium, nickel, arsenic and copper which are generated from electroplating, pulp and paper manufacturing, mining operation, ceramics industry, textile, acid battery production process, pharmaceutical and printing (Siva kiran et al. 2017; Safinejad et al. 2017). These heavy metals enter the plants, animals and human bodies through food chain which affects their health and functional activity (Safinejad et al. 2017; Yao et al. 2016; Schullehner et al. 2017). Among these metals, Pb(II) ion due to its toxicity and suspected carcinogenicity is hazardous to the aquatic ecosystem and poses possible human health risk. Lead ion is seen as a long-standing environmental contaminant which is highly toxic and hazardous to the aquatic ecosystem and poses possible human health risk. Due to the harmful effect of lead on human health and environment, World Health Organization (WHO) has already imposed strict law on the maximum permissible concentration for lead in drinking water as 0.05 mg/L (Uzun and Debik 2019).

Various methods for the removal of these heavy metals from industrial wastewater have been developed such as electrochemical treatment (Kobya et al. 2016), coagulation/flocculation (Luo et al. 2017; Gaikar et al. 2016; Sen et al. 2017), adsorption (Berber-Villamar et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2016a, b), ion exchange processes (Yang et al. 2015; Ansari et al. 2017), solvent extraction (Lam et al. 2018) and membrane filtration (Samadder et al. 2017; Aravind et al. 2018). Among all the stated techniques, adsorption process appears to be the alternative method due to its excellent removal capacity, convenience, economic cost and simplicity (Lalchhingpuii et al. 2017; Okoye et al. 2018; Lu et al. 2018; Lowe et al. 2015). Several adsorbents can be used to treat wastewater, namely commercial activated carbon, silica gel, zeolite and activated alumina, but they are very expensive. For this reason, the use of low-cost adsorbents derived mainly from agricultural materials has attracted wide attention in recent years, due to the presence of certain functional groups such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, amino, ester carbonyl and phosphor (Aravind et al. 2015). Biosorption is one of the recent technologies applied for the removal of heavy metals from an aqueous solution, because of its wide range of target pollutants, high sorption capacity, eco-friendly and low operating cost. This method has been studied by several researches as an alternative to commercial methods for heavy metal removal from wastewaters (Ma et al. 2014; Alqadami et al. 2017; Shojaeimehr et al. 2014; Ashrafi et al. 2017; Sarvani et al. 2018). The major advantages of biosorption technology are its effectiveness in reducing the concentration of heavy metal ions to very low levels and the use of inexpensive biosorbent materials (Miyah et al. 2017; Satayeva et al. 2018; Fan and Zhang 2018; Gouran-Orimi et al. 2018; El Hanache et al.2019). The adsorptive properties of any activated carbon are highly dependent upon active surface sites including functional groups, specific surface area, iodine number and modifications. The removal capabilities of these biosorbents can generally be improved through physical or chemical modification (Kyzas et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2016a, b).

The main objective of the present study is to prepare biosorbent from two agricultural wastes [Africa elemi seed (Canarium schweinfurthii) and mucuna shell (Mucuna pruriens)] and one animal waste material [oyster shell (Crassostrea virginica)] and to explore their potential for the removal Pb(II) from an aqueous solution. The three biosorbents used in this study were examined using one factor at a time (OFAT) for the Pb(II) removal efficiency in order to determine the range of values of process parameters, with an idea to optimize the parameters and to understand the interaction between the factors impacting overall adsorption efficiency using response surface methodology (RSM). The removal efficiency may be developed by optimizing these factors (Gadekar and Ahammed 2019; Archin et al. 2019). RSM is applied as a statistical tool to optimize and study the interaction. Therefore, the RSM-BBD is carried out to evaluate the relationship, and interactions of the factors involve the following steps:

-

Design of the experiment: three-level designs such as the Box–Behnken design (BBD).

-

Regression and statistical analysis: developing models and graphical representation of the response surface (3D, contour plots).

-

Optimization of the variables using the response model to achieve the desirable target.

-

The use of the analysis of variance to check the validity of the models by comparing the predicted model and the experimental values.

Materials and methods

Collection and preparation of materials

Africa elemi seeds (AES), mucuna shell (MS) and oyster shell (OS) were collected from local markets. The materials were ground, washed with 0.5% HCl to remove dirt and dried in an oven at 105 °C. It is then carbonized in a furnace at 500 °C for 2 h. The char produced from each material was then impregnated with orthophosphoric acid, and the ratio was calculated using:

where \( {\text{W}}_{{{\text{H}}_{3} {\text{PO}}_{4} }} \) is dry weight (g) of orthophosphoric acid pellet and \( W_{\text{sample}} \) is dry weight (g) of char. Then, the impregnated samples were dehydrated in an oven at 110 °C and activated in muffled furnace of 450 °C for 1 h. The activated samples were soaked in deionized water several times for half an hour with constant stirring after cooling, washed until pH of each sample filtrate reached (6–8). The sample was dried in an oven at 105 °C and stored in airtight container for further characterization and adsorption studies.

Preparation of Pb(II) stock solution

Stock solution of Pb(II) (1000 mg L−1) was prepared by dissolving required amount of Pb(II) nitrate [Pb(No3)2, Sigma-Aldrich] in double-distilled water. Different concentrations of Pb(II) ion for experimental purposes were prepared by diluting the stock solution with suitable volume of double-distilled water. The initial pH of Pb(II) solution was adjusted using sodium hydroxide (NaOH, Merk) or hydrochloric acid (HCl, Merk) solution using a digital pH meter (ELICO).

Characterization of the adsorbent

Point of zero charge (pHzpc)

The point of zero charge is the pH at which the surface of adsorbent has zero net charge (neutral). This can be used to determine the surface charge of an adsorbent at different pH values. Experiments were conducted by preparing 0.01 M KNO3 solution. The solution pH (pH0) was adjusted from 2 to10 with 0.1 M HCl or 0.1 M NaOH. The biosorbents (20 mg) were added to 100 ml of the pH-adjusted solution in an Erlenmeyer flask and agitated with magnetic shaker for 48 h at room temperature. The final pH (pHf) value of supernatant was measured and plotted against the initial pH. The pH at which the curve cuts the initial (pHO) was taken as the point of zero charge (pHPZC).

BET analysis

The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area, pore volume and pore size of the biosorbent were measured using a pore size micrometric (9320 model, USA). A gas mixture of 22.9 mol% nitrogen and 77.1 mol% helium was used for the purpose.

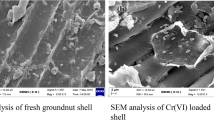

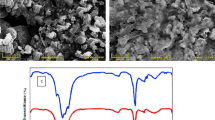

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

The surface morphology of the biosorbents was examined before and after adsorption using scanning electron microscopic SEM (SHIMADZU SS 500).

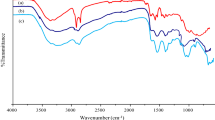

Infrared spectroscopy

The surface functional groups of the biosorbent were determined using Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Prestige 21, Shimadzu) within a range 400–4000 cm−1. In order to identify the main functional groups involved in each process, the Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was used, thus recording the infrared spectrum before and after the adsorption test in the batch system.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The structure of modified biosorbent was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD-6000 Shimadzu) pattern of the biosorbent and was recorded in the range 2 \( \theta = 3 \) at 70 °C.

Batch adsorption experiments

In order to optimize the experimental conditions and to collect data for modeling the study, batch experiment were carried out in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks with 20 mg of the biosorbents in 100 ml aqueous solution of Pb(II) ions at 150 rpm at different concentrations (20–100 mg/L) for equilibrium time of 40 min. The mixtures were agitated using a thermostatic mechanical shaker (HAAKE SWB20, Germany). Various pH values of the solution for the experiment were determined using 0.1 mol/L HCl or 0.1 mol/L NaOH using pH meter (Electronics, Model 101E). Each experiment was conducted in triplicate, and mean values of data were reported. At the end of each experiment, the mixture was centrifuged for 5 min at 4500 rpm to separate the adsorbent from the solution, and the filtrate was analyzed to determine the remaining concentration of Pb(II) ions using UV–visible spectrophotometer (UV-1650A, Shimadzu Japan) at \( \lambda_{ \hbox{max} } \). 560 nm. The quantity of Pb(II) ions adsorbed per gram of the biosorbent at equilibrium, \( q_{\text{e}} \;\left( {{\text{mg}}\;{\text{g}}^{ - 1} } \right) \), is given as:

where \( C_{\text{o}} \;{\text{and}}\; C_{\text{e}} \) are the initial and equilibrium concentrations of Pb(II) ions in the solution (mg L−1), respectively, V is the volume of Pb(II) solution (L) and m is the mass of the biosorbent (g).

The efficiency was calculated as follows:

where \( C_{\text{o}} \;{\text{and}}\;C_{\text{e}} \) are the initial and equilibrium concentrations of Pb(II) ions in the solution (mg L−1), respectively.

Box–Behnken design of experiment

The experimental design for optimization of Pb(II) adsorption onto mucuna seed activated biosorbent (MSA), African elemi seed activated biosorbent (AESA) and oyster shell activated biosorbent (OSA) was done by applying response surface methodology (RSM) through Box-Behnken design. The design which consisted of three levels (low, medium and high coded as − 1, 0 and + 1) was used to optimize the level of chosen variables, that is, adsorbent dosage, pH and contact time. Three independent variables X1, X2 and X3 were applied for statistical calculation with the following mathematical representation:

where \( x_{i} \) is the coded value of an independent variables, \( X_{i} \;{\text{and}}\;X_{o} \) are values of an independent variables and \( \Delta X_{i} \) is the step change value (Damena and Alansi 2018).

In this study, the experimental design and response surface methodology (RSM) were employed using Design Expert software version 9.0.6., USA. The experimental parameters and their levels are presented in Table 1. The range of values of each parameter was obtained from one factor at a time experiments (OFAT) earlier conducted (results not reported). RSM is used to construct a second-order polynomial for assessing the response as a function of independent variables and their interactions as follows:

The response model may be represented as:

where Y is the response variables to be modeled, \( X_{i } \;{\text{and }}\;X_{j} \;{\text{are}} \) the independent variables, and \( \beta_{o} ,\beta_{i} ,\beta_{ii} \;{\text{and}}\;\beta_{ij} \) are regression coefficients for intercept, linear, quadratic and interaction coefficient, respectively (Jadhav and Mahajan 2013).

Results and discussion

Point of zero charge

The point of zero charge of the adsorbents was determined using salt addition method (Mahmood et al. 2011), to investigate the surface behavior of adsorbent and the influence of pH in an adsorption process. From the results obtained, the pH(PZC) of Pb-MSA, Pb-AESA and Pb-OSA system is shown to be pH 8.1, 6.6 and 5.6, respectively (Fig. 1). If the pH of the surroundings were below pH(PZC), the surface of the absorbent was positively charged, and then, the adsorption would be difficult due to charge repulsion (Gu et al. 2018). The Pb(II) ions are found in this form in the acidic conditions with pH values below 6.5, when the soluble species are governed by Pb2+ and Pb(OH)+, and as Pb(OH)2 form when the pH > 6.5 (Tu et al. 2017). At low pH values, there is a competition between Pb(II) ions and the concentration of H+ ions presented in solution. With increasing pH, fewer hydrogen proton are present in solution, so more binding sites are released, resulting in the increase in the adsorption of Pb(II) on the binding site. This indicates that below this pH, the activated carbon acquires positive charge due to protonation of functional groups which results in electrostatic attraction between Pb(II) anions, whereas above this pH, a negative charge exists on the surface of MSA, AESA and OSA. Hence, the adsorption of anionic Pb(II) is favored at pH less than pH(PZC) where the surface of adsorbent becomes positively charge (Chen et al. 2016a, b; Ranote et al. 2019; Osasona et al. 2015). Thus, similar result has been reported (Yin et al. 2018).

FTIR spectra analysis

The FTIR technique is an important tool used to identify the characteristic functional groups on the surface of the biosorbent (Ghaedi et al. 2014). The spectra of the biosorbents were measured within the range of 500–4000 cm−1 wave number. Figures 2, 3 and 4 demonstrate the results of FTIR spectra of MSA, AESA and OSA before adsorption of Pb(II). The FTIR spectra display a number of peaks pertaining to different functional groups, which reflects the complex nature of the biomass. The broad and intense peaks at 3937.74–3544.56 cm−1 in MSA-Pb, AESA-Pb and OSA-Pb are due to the stretching of the N–H bond of amino groups and indicative of bonded hydroxyl group involved in the reaction (Wang et al. 2016a; Dil et al. 2017; Zeng et al. 2015). The peaks at 2868.29 cm−1 is assign to aldehyde group of –O–CH3, while the bend at 2064.51 cm−1 is attributed to vibration in the alkyn group (Song and Li 2019). The peaks at 1853.59 and 1757.15 cm−1 are assigned to O–H, H bonded H stretch, carbonyl stretching of aldehyde (Dil et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2016a). The C=C stretch of aromatic alkene or N–H group of amino acid is represented by the bands at 1647.21, 1566.13 and 1517.98 cm−1 (Song and Li 2019; Ranote et al. 2019). The peak at 1440.83 cm−1 is assigned to O–H bend in carboxylic acid. The peaks from 1300 to 1043.49 cm−1 are attributed to the presence of carboxyl and phosphate groups (Oliveira et al. 2016). The peak at 879 cm−1 is assigned to C–C stretch and N–H rocking (Zeng et al. 2015). The band at 428.2 cm−1 is assigned to C–I aromatic ring deformation. In Fig. 2, the peak at 3429.43 cm−1 is due to the stretching of the N–H bond of amino groups. Also the peak at 2372.44 is assigned C=C stretch of alkyne. The peaks at 1874.81 and 1757.15 cm−1 are assigned to O–H, H bonded H stretch, carbonyl stretching of aldehyde. The C=C stretch of aromatic alkene or N–H group of amino acid is represented by the bands at 1654.92 and 1568.13 cm−1. The peak at 1440.83 and 1421.54 cm−1 is assigned to O–H bend in carboxylic acid. In all samples spectra, the peaks at 1111.00 and 1035.77 cm−1 are attributed to the presence C–H, CO deformation or stretching vibrations in different groups of lignin and carbohydrate (Hajji et al. 2017). The peak at 877.61 cm−1 shows the presence of aromatic –CH stretching. The peaks at 710.26 and 608.65 are assigned to N–H rocking, C–H rocking, C–Cl stretching. The peaks at 528.50, 493.78 and 428.27 cm−1 are assigned to C–Br stretching, C–I aromatic ring deformation. The FTIR spectra of the adsorbents after adsorption (figures are not shown) show that some peaks shifted or disappeared and also new peaks appeared. This proves the interaction effects due to involvement of the functional groups in the adsorption process. This change may be responsible for chemical interaction of lead ions with the functional groups corresponding to these peaks. A similar result was also reported for cassava starch treated with citric acid (Mei et al. 2015).

X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD)

X-ray diffraction technique is a powerful tool used to analyze the crystalline nature of material. The crystalline compositions of the activated carbon are shown in Figs. 5, 6 and 7 for MSA, AESA and OSA. MSA and AESA show almost the same appearance and reveal the existence of major peaks at 20° and 21° for MSA 14° and 18° for AESA of kaolinite and mica/illite, which correspond to the pattern of the amorphous nature (Bahoria et al. 2018; Yin et al. 2018), while OSA shows many peaks corresponding to the position 2 \( \theta \) 21°, 26°, 27°, 29°, 31°, 33°, 36°, 38°, 39°, 41°, 43°, 46°, 48°, 50° and 53°, respectively, whereas mica/illite predominate over quartz (Jiang et al. 2018; Benafqir et al. 2019). If the material under investigation is crystalline, well-defined peaks are observed, while non-crystalline or amorphous system shows a hollow instead of well-defined peaks (Hajji et al. 2017; Zhao et al. 2017).

SEM (scanning electron microscopy)

The surface morphology of the biosorbent before and after adsorption at a magnification was used to study the surface morphology and pore variations of activated carbon, and its results are shown in Figs. 8, 9 and 10. After modification with orthophosphorous acid, many various sizes of pores like honeycomb can be observed on some samples surface. From the figures, it shows the pores and cavities which provide a large surface area for trapping of particles within the pores. This can be confirmed from the figure, because the surface roughness changed significantly and the pores are packed with deposited Pb(II) ions after adsorption (Sharma et al. 2019). Similar types of pore arrangement were observed by Ranote et al. (2019).

Development of RSM model

RSM is a capable statistical tool that gives a better result of reproducibility and process optimization for predictive model (Damena and Alansi 2018). Also a total of 27 experiments were conducted. BBD matrix for experimental design (real and coded values of the three factors such as adsorbent dose, pH and contact time) for observed and predicted responses for the removal of Pb(II) ions is given in Table 2, using Design Expert software version 9.0.6., USA. Second-order polynomial equations were used to draw relationship between independent variables and responses. The effects of the parameters and response behavior of the system are explained by Eqs. 5 to 7 as shown below. Within the chosen range of experiments, the optimum adsorbent dose, pH and contact time for MSA were at 100 mg, pH 6 and contact time of 40 min at 99.59% removal of Pb(II) ions. With AESA, the removal was 99.59% with 100 mg, pH 2 and contact time of 70 min, while the OSA removed 98.18% with 100 mg, pH 6 and contact time 40 min. Optimized results were obtained at desirability of 1.00, indicating the applicability of the developed models. The desirability value closer to 1.00 is considered most desirable (Mondal et al. 2018).

Analysis of variance (ANOVA)

The ANOVA results obtained for the three models are presented in Tables 3, 4 and 5 indicating that all the models were significant because the F-values obtained are 31.76222, 42.83089 and 229.9161 for MSA, AESA and OSA, with a low probability value (p < 0.0001). The greater the F-value, the more certain it is that the model explains adequately the variation in the data, and the estimated significant terms of the adsorbents variables are closer to the actual value (Roshanak et al. 2015; Kumari and Gupta 2018). Also the p values for the quadratic models for the adsorbents were less than 0.05, indicating that the model is significant. If the p values are higher than 0.10, the model terms are not significant. Also there are other statistical parameters that determine significance of a models, such as coefficient of determination R2, adjusted R2, predicted R2 and coefficient variation (CV%). The coefficient of determination \( R^{2} \) is close to 1, which means a better correlation between the experimental and predicted (Asfaram et al. 2015; Li et al. 2016). The \( R^{2} \) values of 0.9470, 0.9578 and 0.993 for MSA, AESA and OSA indicate that the models could not explain 5.3%, 4.22% and 0.77%. The ‘adequate precision’ ratio should be higher than 4 so that the predicated models can be used to navigate the space (Kumari and Gupta 2018). Small values of CV and SD reflect reproducibility of the models; the values of CV, SD and AP are also presented in Tables 6, 7 and 8. The CV values of 1.23, 0.98 and 0.67 were obtained for MSA, AESA and OSA, respectively. Adequate precision (AP) results show that any value that exceeds 4 indicates that the model will give a reasonable performance in prediction (Roshanak et al. 2015).

Adequacy of a model

It is usually necessary to check the fitted model to ensure it provides an adequate approximation to the real system. Normalization plots in Figs. 11, 12 and 13 helps in judging whether the models are satisfactory. Figure 11a shows that the data are plotted against a theoretical normal distribution in such a way that the points should form an approximate straight line and a departure from this line would indicate a departure from a normal distribution. From the result, the data points are slightly deviating from the normal distribution given, but not very critical. Figure 11b for residual plots shows that the data points are scattered randomly and do not form a trend, but all the data points in the plot are within the boundaries marked by the red lines. Therefore, there were no outlier data. The predicted versus actual, in Fig. 11c, shows that all the data points are distributed along the 45° line, indicating that the model can provide an acceptable fit for the experimental data (Mondal et al. 2017). Similar results are shown in Figs. 12 and 13 for AESA and OSA.

Model analysis of response surface plots

The 3D response surface plots are the graphical representation of the regression equations used to observe the relationship between the responses and experimental levels of each factor. These plots are shown in Figs. 14, 15 and 16 for MSA, AESA and OSA. The interaction between pH and adsorbent mass was generated by fixing parameter of contact time center points. At moderate pH, high adsorbent mass results in maximum percentage removal of Pb(II). The percentage removal of Pb(II) increases with increase in adsorbent mass. This is as a result of more amount of adsorbent mass been available for the adsorption of Pb(II) (Havva et al. 2014). The interaction between contact time and adsorbent mass shown in Fig. 14b was generated by fixing pH at center point. At any given adsorbent mass from 10 to 100 mg, an increase in dosage and contact time led to higher percentage removal of Pb(II). The effect of contact time with pH at a fixed adsorbent mass on the percentage removal of Pb(II) is shown in Fig. 14c. From the figure, it was observed that adsorption at high contact time and moderate pH, the percentage removal was maximum. This is due to sufficient surface area available for adsorption (Sravan Kumar et al. 2014). The AESA and OSA show similar behavior in Figs. 15 and 16.

Optimization using the desirability functions

Optimization of Pb(II) ion removal was to find the maximum removal percentage by utilizing minimum adsorbent dosage. It is a value between 0 and 1, and increases as the corresponding response value becomes more desirable. In this study, the input variables were given specific ranged values, whereas the response was design to achieve a maximum. The values were calculated by means of the desirability function using design expert software. From the results, the maximum achieved Pb(II) removal efficiency was 99.59% (Fig. 15) at adsorbent dosage of 26.66 mg, initial pH 6.67 and contact time 69.0 min at maximum desirability value of 1.0 for MSA. In Fig. 16 for AESA, the 99.59% removal was achieved with adsorbent mass of 63.54 mg, pH 4.8 and contact time of 66.8 min at maximum desirability of 1.0. In Fig. 17 for OSA, the 98.21% removal was at adsorbent mass of 96.87 mg, pH of 5.92 and contact time of 69.36 at maximum desirability of 1.0.

Model validation and confirmation experiments

The optimized conditions generated during response surface methodology were validated by conducting adsorption experiments with the optimum parameters. Experimental validation is the final step in the modeling process to investigate the accuracy and robustness of the established models. The results of predicted and experimental values of the output variables are given in Table 9. Also the maximum error (%) between the predicted values and experimental values was less than 3%, indicating that the quadratic models adopted could predict experimental results well (Sharma et al. 2009). Therefore, it can be concluded that the models accurately represent Pb(II) ion removal over the experimental range studied (Figs. 18, 19).

Conclusion

In this study, application of modified biosorbents AESA, MSA and OSA for the adsorption of Pb(II) ions was investigated by an RSM with Box–Behnken design. All the biosorbents were characterized by FTIR, SEM and XRD. The FTIR analysis confirmed the role of surface functional groups present on the biosorbents in the biosorption process. The RSM model was used to examine the effect of three process variables on removal of Pb(II) ions. Variance analysis and 3-D response surface plots all indicated that the initial pH was the most significant factor in the removal process. The ANOVA results clearly suggest that the models developed for adsorption of Pb(II) ions onto MSA, AESA and OSA were highly significant base on low p values. This study shows that the above-mentioned biosorbents are alternative low-cost materials for the treatment of Pb(II) contaminated water.

References

Adewuyi A, Pereira FV (2017) Underutilized Luffa cylindrical sponge: a local bio-adsorbent for the removal of Pb(II) pollutant from water system. Beni Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci 6:118–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjbas.2017.02.001

Aguilar L, Gallegos A, Arias CA, Ferrera I, Sanchez O, Rubio R, Ben Saad M, Missagia B, Caro P, Sahuquillo S et al (2019) Microbial nitrate removal efficiency in groundwater polluted from agricultural activities with hybrid cork treatment wetlands. Sci Total Environ 653:723–734

Alqadami AA, Naushad M, Abdalla MA et al (2017) Efficient removal of toxic metal ions from wastewater using a recyclable nanocomposite: a study of adsorption parameters and interaction mechanism. J Clean Prod 156:426–436

Ansari MH, Parsa JB, Arjomandi J (2017) Application of conducting polyaniline, o-anisidine, o-phenetidine and ochloroaniline in removal of nitrate from water via electrically switching ion exchange: modeling and optimization using a response surface methodology. Sep Purif Technol 179:104–117

Aravind J, Sudha G, Kanmani P, Devisri AJ, Dhivyalakshmi S, Raghavprasad M (2015) Equlibrium and kinetic study on chromium(VI) removal from simulated waste water using gooseberry seeds as a novel biosorbent. Glob J Environ Sci Manag 1(3):233–244

Aravind P, Selvaraj H, Ferro S, Neelavannan GM, Sundaram M (2018) A one-pot approach: oxychloride radicals enhanced electrochemical oxidation for the treatment of textile dye wastewater trailed by mixed salts recycling. J Clean Prod 182:246–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.064

Archin S, Sharifi SH, Asadpour G (2019) Optimization and modeling of simultaneous ultrasound-assisted adsorption of binary dyes using activated carbon from tobacco residues: response surface methodology. J Clean Prod 239:118136

Asfaram A, Ghaedi M, Goudarzi A, Rajabi M (2015) Response surface methodology approach for optimization of simultaneous dye and metal ion ultrasound-assisted adsorption onto Mn doped Fe3O4-NPs loaded on AC: kinetic and isothermal studies. Dalton Trans 44:14707–14723

Ashrafi M, Chamjangali M, Bagherian G, Goudarzi N, Kavian S (2017) Evaluation of nanosilica, extracted from stem sweep, as a new adsorbent for simultaneous removal of crystal violet and methylene blue from aqueous solutions. Desalin Water Treat 88:207–220. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2017.21425

Azari A Gharibi, Kakavandi H, Ghanizadeh B, Javid G, Mahvi AH (2017) Magnetic adsorption separation process: an alternative method of mercury extracting from aqueous solution using modified chitosan coated Fe3O4 nanocomposites. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 92:188–200

Bahoria BV, Parbat DK, Nagarnaik PB (2018) XRD analysis of natural sand, quarry dust, waste plastic (ldpe) to be used as a fine aggregate in concrete. Mater Today Proc 5(1):1432–1438

Benafqir M, Abbaz Z, Anfar M (2019) Hematite-titaniferous sand as a new low-cost adsorbent for orthophosphates removal: adsorption, mechanism and Process Capability study. Environ Technol Innov 13:153–165

Berber-Villamar NK, Netzahuatl-Muñoz AR, Morales-Barrera L, Chavez-Camarillo GM, Flores-Ortiz CM, Cristiani-Urbina E (2018) Corncob as an effective, eco-friendly, and economic biosorbent for removing the azo dye Direct Yellow 27 from aqueous solutions. PLoS ONE 13(4):e0196428. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196428

Chen D, Zhang H, Yang K, Wang H (2016a) Functionalization of 4-aminothiophenol and 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane with grapheme oxide for potential dye and copper removal. J Hazard Mater 310:179–187

Chen B, Liu Y, Chen S, Zhao X, Meng X, Pan X (2016b) Magnetically recoverable cross-linked polyethylenimine as a novel adsorbent for removal of anionic dyes with different structures from aqueous solution. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 67:191–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2016.07.014

Damena T, Alansi T (2018) Review: low cost, environmentally friendly humic acid coated magnetite nanoparticles (HA-MNP) and its application for the remediation of phosphate from aqueous media. J Encapsulation Adsorpt Sci 8:256–279

Dil EA, Ghaedi M, Asfaram A (2017) The performance of nanorods material as adsorbent for removal of azo dyes and heavy metal ions: application of ultrasound wave, optimization and modeling. Ultrason Sonochem 34:792–802

El Hanache L, Sundermann L, Lebeaua B, Toufaily J, Hamieh T, Daoua TJ (2019) Surfactant-modified MFI-type nanozeolites: super-adsorbents for nitrate removal from contaminated water. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 283:1–13

Fan C, Zhang Y (2018) Adsorption isotherms, kinetics and thermodynamics of nitrate and phosphate in binary systems on a novel adsorbent derived from corn stalks. J Geochem Explor 188:95–100

Gadekar MR, Ahammed M (2019) Modelling dye removal by adsorption onto water treatment residuals using combined response surface methodology-artificial neural network approach. J Environ Manag 231:241–248

Gaikar P, Pawar SP, Mane RS (2016) Synthesis of nickel sulfide as a promising electrode material for pseudocapacitor application. Desalination Water Treat 57(39):18551–18559

Ghaedi M, Hosaininia R, Ghaedi AM, Vafaei A, Taghizadeh F (2014) Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system model for adsorption of 1,3,4-thiadiazole-2,5- dithiol onto gold nanoparticales-activated carbon. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 131:606–614

Gouran-Orimi R, Mirzayi B, Nematollahzadeh A, Tardast A (2018) Competitive adsorption of nitrate in fixed-bed column packed with bio-inspired polydopamine coated zeolite. J Environ Chem Eng 6:2232–2240

Gu P, Zhang S, Li X (2018) Recent advances in layered double hydroxide-based nanomaterials for the removal of radionuclides from aqueous solution. Environ Pollut 240:493–505

Hajji S, Slama RB, Salem B, Hamdi M, Jellouli K, Ayadi W, Nasri M, Boufi S (2017) Nanocomposite films based on chitosan–poly(vinyl alcohol) and silver nanoparticles with high antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Process Saf Environ Prot 111:112–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2017.06.018

Havva T, TolgaKartal S, Yigitarslan Y (2014) Optimization of lead adsorption of mordenite by response surface methodology: characterization and modification. J Environ Health Sci Eng 12:1–9

Jadhav MV, Mahajan YS (2013) Investigation of the performance of chitosan as a coagulant for flocculation of local clay suspension of different turbidities. KSCE J Civ Eng 17(2):329–334

Jiang C, Guo W, Chen H, Zhu Y, Jin C (2018) Effect of filler type and content on mechanical properties and microstructure of sand concrete made with superfine waste sand. Constr Build Mater 192:442–449

Kobya M, Gengec E, Demirbas E (2016) Operating parameters and costs assessments of a real dyehouse wastewater effluent treated by a continuous electrocoagulation process. Chem Eng Process Process Intensif 101:87–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cep.2015.11.012

Kumari M, Gupta SK (2018) Removal of aromatic and hydrophobic fractions of natural organic matter (NOM) by surfactant modified magnetic nanoadsorbents (MNPs). Environ Sci Pollut Res 25(25):25565–25579

Kyzas GZ, Siafaka PI, Pavlidou EG, Chrissafis KJ, Bikiaris DN (2015) Synthesis and adsorption application of succinyl-grafted chitosan for the simultaneous removal of zinc and cationic dye from binary hazardous mixtures. Chem Eng J 259:438–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2014.08.019

Lalchhingpuii, Tiwari D, Lalhmunsiama, Lee SM (2017) Chitosan templated synthesis of mesoporous silica and its application in the treatment of aqueous solutions contaminated with cadmium(II) and lead(II). Chem Eng J 328:434–444

Lam SM, Low XZD, Wong KA, Sin JC (2018) Sequencing coagulation–photodegradation treatment of Malachite Green dye and textile wastewater through ZnO micro/nanoflowers. Chem Eng Commun 205:1143–1156. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986445.2018.1434163

Li S, Xiong Q, Lai X, Li X, Wan M, Zhang J, Yan Y, Cao M, Lu L, Guan J, Zhang D (2016) Molecular modification of polysaccharides and resulting bioactivities. Compr Rev Food Sci F. 15:237–250

Lowe BM, Skylaris CK, Green NG (2015) Acid-base dissociation mechanisms and energetics at the silica-water interface: an activationless process. J Colloid Interface Sci 451:231–244

Lu JS, Lian T, Su J (2018) Effect of zero-valent iron on biological denitrification in the autotrophic denitrification system. Res Chem Intermed 44:6011–6022

Luo W, Phan HV, Xie M, Hai FI, Price WE, Elimelech M, Nghiem LD (2017) Osmotic versus conventional membrane bioreactors integrated with reverse osmosis for water reuse: biological stability, membrane fouling, and contaminant removal. Water Res 109:122–134

Ma W, Zong P, Cheng Z, Wang B, Sun Q (2014) Adsorption and bio-sorption of nickel ions and reuse for 2-chlorophenol catalytic ozonation oxidation degradation from water. J Hazard Mater 266:19–25

Mahmood T, Saddique MT, Naeem A, Westerhoff P, Mustafa S, Alum A (2011) Comparison of different methods for the point of zero charge determination of NiO. Ind Eng Chem Res 50:10017–11003

Mei J-Q, Zhou D-N, Jin Z-Y, Xu X-M, Chen H-Q (2015) Effects of citric acid esterification on digestibility, structural and physicochemical properties of cassava starch. Food Chem 187:378–384

Miyah Y, Lahrichi A, Idrissi M, Boujraf S, Taouda H, Zerrouq F (2017) Assessment of adsorption kinetics for removal potential of Crystal Violet dye from aqueous solutions using Moroccan pyrophyllite. J Assoc Arab Univ Basic Appl Sci 23:20–28

Mondal NK, Samanta A, Dutta S, Chattoraj S (2017) Optimization of Cr(VI) biosorption onto Aspergillus niger using 3-level Box–Behnken design: equilibrium, kinetic, thermodynamic and regeneration studies. J Genet Eng Biotechnol 15(1):151–160

Mondal SK, Saha AK, Sinha A (2018) Removal of ciprofloxacin using modified advanced oxidation processes: kinetics, pathways and process optimization. J Clean Prod 171:1203–1214

Okoye CC, Onukwuli OD, Okey-Onyesolu CF (2018) Utilization of salt activated Raphia hookeri seeds as biosorbent for Erythrosine B dye removal: kinetics and thermodynamics studies. J King Saud Univ Sci 31:1–10

Oliveira TIS, Rosa MF, Cavalcante FL, Pereira PHF, Moates GK, Wellner N (2016) Optimization of pectin extraction from banana peels with citric acid by using response surface methodology. Food Chem 198:113–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.08.080

Osasona I, Adebayo AO, Okoronkwo AE, Ajayi OO (2015) Acid and alkali modified cow hoof powder as adsorbents for chromium(VI) as adsorbents for chromium(VI) removal from aqueous phase. Iran J Energy Environ 6(4):290–300

Ranote S, Kumar D, Kumari S, Kumar R, Chauhan GS, Joshi V (2019) Green synthesis of Moringa oleifera gum–based bifunctional polyurethane foam braced with ash for rapid and efficient dye removal. Chem Eng J 361:1586–1596

Roshanak K, Mansor B, Ahmad H, Reza Fard M (2015) Rapid adsorption of copper(II) and lead(II) by rice straw/Fe3O4 nanocomposite: optimization, equilibrium isotherms and adsorption kinetics study. PLoS ONE 10:1–19

Safinejad A, Chamjangali MA, Goudarzi N, Bagherian G (2017) Synthesis and characterization of a new magnetic bio-adsorbent using walnut shell powder and its application in ultrasonic assisted removal of lead. J Environ Chem Eng 5(2):1429–1437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2017.02.027

Samadder SR, Prabhakar R, Khan D (2017) Analysis of the contaminants released from municipal solid waste landfill site: a case study. Sci Total Environ 580:593–601

Sarvani R, Damani E, Ahmadi Sh (2018) Adsorption isotherm and kinetics study: removal of phenol using adsorption onto modified Pistacia mutica shells. Iran J Health Sci 6:33–42

Satayeva AR, Howell CA, Korobeinyk AV, Jandosov J, Inglezakis VJ, Mansurov ZA, Mikhalovsky SV (2018) Investigation of rice husk derived activated carbon for removal of nitrate contamination from water. Sci Total Environ 630:1237–1245

Schullehner J, Stayner L, Hansen B (2017) Nitrate, nitrite, and ammonium variability in drinking water distributio systems. Int J Environ Public Health 14:1–9

Sen S, Dutta S, Guhathakurta S, Chakrabarty J, Nandi S, Dutta A (2017) Removal of Cr(VI) using a cyanobacterial consortium and assessment of biofuel production. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 119:211–224

Sharma YC, Srivastava V, Singh VK, Kaul SH, Weng CH (2009) Nanoadsorbents for the removal of metallic pollutants from water and wastewater. Environ Technol 30(6):583–609

Sharma A, Syed Z, Brighu U, Gupta AB, Ram C (2019) Adsorption of textile wastewater on alkali-activated sand. J Clean Prod 220:23–32

Shojaeimehr T, Rahimpour F, Khadivi MA, Sadeghi M (2014) A modeling study by response surface methodology (RSM) and artificial neural network (ANN) on Cu2+ adsorption optimization using light expended clay aggregate (LECA). J Ind Eng Chem 20:870–880

Siva Kiran RR, Madhu GM, Satyanarayana SV, Kalpana P, Subba Rangaiah G (2017) Applications of Box–Behnken experimental design coupled with artificialneural networks for biosorption of low concentrations of cadmium using Spirulina (Arthrospira) spp. Resour Effic Technol 3:113

Song M, Li M (2019) Adsorption and regeneration characteristics of phosphorus from sludge dewatering filtrate by magnetic anion exchange resin. Environ Sci Pollut Res 26:34233–34247

Sravan Kumar D, Ramachandramurthy VC, Dayana K, Sowjanya CVN (2014) Application of response surface methodology (RSM) for the removal of nickel using rice husk ash as biosorbent. Int J Eng Res Gen Sci 2:162–176

Tu Y-J, You C-F, Chen M-H, Duan Y-P (2017) Efficient removal/recovery of Pb onto environmentally friendly fabricated copper ferrite nanoparticles. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. E 71:197–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2016.12.006

Uzun HI, Debik E (2019) Economical approach to nitrate removal via membrane capacitive deionization. Sep Purif Technol 209:776–781

Wang Y, Li L, Luo C, Wang X, Duan H (2016a) Removal of Pb2+ from water environment using a novel magnetic chitosan/graphene oxide imprinted Pb2+. Int J Biol Macromol 86:505–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.01.035

Wang N, Xu X, Li H (2016b) Preparation and application of a xanthate-modified thiourea chitosan sponge for the removal of Pb(II) from aqueous solutions. Ind Eng Chem Res 55:4960–4968

Yang C, Li L, Shi J, Long C, Li A (2015) Advanced treatment of textile dyeing secondary effluent using magnetic anion exchange resin and its effect on organic fouling in subsequent RO membrane. J Hazard Mater 284:50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.11.011

Yao S, Zhang J, Shen D, Xiao R, Gu S, Zhao M, Liang J (2016) Removal of Pb(II) from water by the activated carbon modified by nitric acid under microwave heating. J Colloid Interface Sci 463:118–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2015.10.047

Yin Z, Wang Y, Wang K, Zhang C (2018) Adsorption behavior of hydroxypropyl guar gum onto quartz sand. J Mol Liq 258:10–17

Zeng G, Liu Y, Tang L (2015) Enhancement of Cd(II) adsorption by polyacrylic acid modified magnetic mesoporous carbon. Chem Eng J 259:153–160

Zhao B, Xiao W, Shang Y, Zhu H, Han R (2017) Adsorption of light green anionic dye using cationic surfactant-modified peanut husk in batch mode. Arab J Chem 10:S3595–S3602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2014.03.010

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okolo, B.I., Oke, E.O., Agu, C.M. et al. Adsorption of lead(II) from aqueous solution using Africa elemi seed, mucuna shell and oyster shell as adsorbents and optimization using Box–Behnken design. Appl Water Sci 10, 201 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-020-01242-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-020-01242-y