Abstract

Cancer pain is a common symptom experienced by patients, caused either by the disease or its treatment. Morphine remains the most effective and recommended treatment for cancer pain. However, cancer patients still do not receive appropriate management for their pain, and under-treatment is common. Lack of knowledge and negative attitudes towards cancer pain and analgesia among professionals, patients and family caregivers are reported as one of the most common barriers to effective cancer pain management (CPM). To systematically review research on the nature and impact of attitudes and knowledge towards CPM, a systematic literature search of 6 databases (the Cochrane library, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science and EMBASE) was undertaken in July 2018. Additionally, hand-searching of Google, Google Scholar and reference lists was conducted. The inclusion criteria were adult (18–65 years of age), studies which included attitudes and knowledge towards CPM, studies written in English, published literature only and cross-sectional design. Included studies were critically appraised by two researchers independently using the Joanna Briggs Institute Analytical Cross Sectional Studies Assessment (JBI-ACSSA). A total of 36 studies met the inclusion criteria. The main finding was that among professionals, patients, caregivers and the public there were similar attitudinal barriers to effective CPM. The most commonly cited barriers were fear of drug addiction, tolerance of medication and side effects of opioids. We also found differences between professional groups (physicians versus nurses) and between different countries based on their potential exposure to palliative care training and services. There are still barriers to effective CPM, which might result in unrelieved cancer pain. Therefore, more educational programmes and training for professionals on CPM are needed. Furthermore, patients, caregivers, and the public need more general awareness and adequate level of knowledge about CPM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer has become the most common cause of death worldwide [7, 86]. It has been estimated that by 2030, there will be about 21.4 million new cancer cases annually, and approximately 13.3 million cancer patients expected to be die from the disease [31]. Pain related to cancer is a common problem that can occur among patients who are having active cancer treatment [47].This can be a result of some complications following treatment of cancer, which can be physical or psychological symptoms [21, 73]. The prevalence of cancer pain can be associated with the stage of disease and the location of cancer [36, 41]. According to a recent meta-analysis, pain was reported by more than 50% of cancer patients who received anti-cancer treatment and about 66% of patients with advanced and metastatic cancer [26]. Several attempts have been made to establish effective CPM. One of the most important attempts is the “analgesic ladder,” established by the World Health Organisation (WHO), to manage cancer pain in adult patients [91]. Morphine remains the most effective and recommended treatment for CPM [99, 103]. Despite the improving quality of pharmacological options for pain management, several studies have revealed that patients at different stages of their disease still do not receive appropriate CPM [3, 18, 25, 37, 52, 92]. Lack of knowledge and negative attitudes towards CPM among professionals [1, 18, 80, 82, 93], cancer patients [61] and family caregivers [79] were reported by recent reviews and studies as one of the most common barriers to effective CPM.

Numerous studies conducted worldwide have assessed independently either professionals’, patients’, caregivers’, or the publics’ attitudes and knowledge towards CPM. However, synthesis of these results has not yet been undertaken. Conducting such a review is important as it is now well established from a variety of studies that many common barriers delay the delivery of effective CPM to patients; this could be caused by professionals [9, 11, 18, 24, 46, 80, 83, 84], cancer patients [57], caregivers [95] and the general public [51], which is likely to result in inadequate CPM. Thus, the aim of this systematic review is to determine the nature and impact of attitudes and knowledge towards CPM.

Methods

Protocol and Registration

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement has been used as a guideline for reporting the findings in this systematic review [53, 63, 85]. The protocol for this review was registered with PROSPERO; the registration number is CRD42018117625.

Adapting PICO into PCO for This Current Systematic Review

The types of studies, participants and interventions, as well as the types of outcome measures (PICO) will be modified to PCO (population, context and outcome) as there are no interventions or comparisons needed. [78, 89]. For more details, see Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria: Population, Context and Outcome

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 2

Search Strategy for Identification of Studies

In this systematic review, we searched 6 electronic databases (the Cochrane library, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science and EMBASE) in July 2018. Additionally, hand-searching of Google, Google Scholar and reference lists was conducted. The search terms were based on population, contexts (context pain, context opioids and context cancer) and outcome [16]. To identify publications for inclusion in the present systematic review, the keywords employed were as shown in Table 3. For more information regarding search strategy, see Appendix 5.

Data Extraction

The data extraction form was developed and piloted independently by two reviewers (SM & SP). A third reviewer (MB) was involved to reconcile any disagreements. Using data extraction forms can potentially reduce bias and improve validity and reliability [17]. In this review, the data extraction form was adapted from Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York [17] (see Appendix 1). The extraction of data from the included studies was based on the names of authors, year, country of publication, design of study, the aim of study, sample size, the setting of study, mean age, sex ratio, type of measurements, type of sample, type of cancer, main findings and the quality of study as outlined in Table 4.

Quality Assessment of the Included Studies

The reason for using a critical appraisal process for the included studies was that studies can be published with variable levels of methodological rigour and therefore their results could be unreliable [15]. It has been strongly recommended that the assessment of quality should be done separately by at least two reviewers [56, 64, 72, 90]. Accordingly, all 36 included studies have been critically apprised by two researchers (SM & SP) independently using the Joanna Briggs Institute Analytical Cross Sectional Studies Assessment (JBI-ACSSA) (see Appendix 2). To reconcile any differences, a third reviewer (MB) was involved. The JBI-ACSSA tool was chosen as it is appropriate for the study design of included quantitative studies [64, 90]. The assigning score for the quality of the data was performed as 1 point for each applicable item with a score of 7 as the maximum score [74]. An overall score was calculated for each included study and the rating of quality was judged as good (6/7 and 7/7), fair (3/7 to 5/7) or poor (< 3/7) [35] (see Appendix 3). No score was below 3/7, so no study was excluded based on the quality assessment only.

Results

Information Sources and Study Selection

The total number of studies identified by 6 electronic databases (the Cochrane library, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science and EMBASE) was 6830 articles (see Appendix 5). In addition, 17 studies were identified by hand-searching (including Google, Google Scholar and checking the reference lists). Among these 6847 studies, 5650 articles were included after the duplicate studies were removed. Among the 5650 included studies, 5523 studies were excluded after the title and abstract of each study were carefully reviewed. The total number of full-text articles assessed for eligibility was 133. A further 97 studies were excluded and all full references of these excluded articles and the reasons for exclusion are listed in Appendix 4. Consequently, a total number of 36 studies were included in this review as illustrated in Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram for strategy of the study selection. Adapted from Moher et al. [62]

Characteristics of Included Studies

The 36 studies included in this review used a cross-sectional design, employing various questionnaires, to assess knowledge of and attitudes towards CPM. The studies were based in 18 countries. The characteristics of included studies are illustrated in Table 4.

Overall Results of Included Studies

Patients’ Knowledge and Attitudes Towards CPM

The results from the majority of studies with cancer patients reported that the mean scores on patient’s knowledge and attitudes towards CPM were low, indicating poor understanding or negative attitudes towards CPM [19, 20, 57, 77]. For example, a recent study conducted in China by Lou and Shang [57] reported through the Barriers Questionnaire-Taiwan (BQT; ranged from 0 to 5) that patients had negative attitudes towards CPM in six areas (scores ≥ 2.5), “tolerance” (3.83 ± 0.96), “use of analgesics as needed (p.r.n.)” (3.73 ± 1.01), “addiction” (3.44 ± 1.05), “disease progression” (3.28 ± 1.26), “distraction of physicians” (3.16 ± 1.07) and “side effects” (2.99 ± 0.68), which can lead to attitudinal barriers towards effective CPM [2]. Another example [20] is that more than 50% of Turkish patients refused to receive strong opioids, such as morphine, and 36.8% of them preferred another (non-opioid) medication for managing their cancer pain.

Professionals’ Knowledge and Attitudes Towards CPM

Several studies showed that physicians had better knowledge and attitudes towards CPM compared with nurses [22, 32, 44, 45]. For instance, it has been reported that physicians who work at oncology units had higher understanding and knowledge about CPM than nurses. The mean scores on the KAS (range 0–39) for physicians was 24.3 (62.3%) compared with 20.08 (51.5%) for nurses (p < 0.001) [22]. The outcomes also showed that oncologists recorded higher knowledge of CPM than surgeons (p < 0.001) [33]. An interesting finding, which was reported by McCaffery and Ferrell [59], is that Canadian and American nurses were more likely to use morphine for CPM than nurses in Japan or Spain. For example, 71.5% of Canadian nurses and 66.3% of nurses from America reported using morphine for managing cancer pain, compared with 61.6% of Japanese nurses and 51.2% of nurses from Spain [59]. The results also revealed that there was a degree of misunderstanding regarding opioid addiction by nurses between countries. For instance, the majority of nurses who answered the relevant questions correctly were from Canada and the USA (51.3% and 43.4%), respectively, whereas, only 14% of Spanish nurses and 17.2% of Japanese nurses responded correctly [59]. Another interesting observation to emerge from the results was that there were geographical variations within countries, for example, the nurses who worked in the central region of Italy had lowest score of pain knowledge (47.9%; M = 18; n = 66) compared with those in the north (57.2%; M = 21; n = 149) and in the south of Italy (56.9%; M = 23; n = 72) (p < 0.001) [11].

Family Caregivers’ Knowledge and Attitudes Towards CPM

A study revealed that caregivers’ attitudes towards CPM and the patients’ pain knowledge explained 23.2% of the total variance in the patients’ average scores for their attitudes towards CPM when entered into a regression equation [57]. This indicates that patients’ attitudes towards CPM were influenced by their caregivers’ attitudes and the patient’s pain knowledge [57]. The results from a study conducted in Taiwan indicated that family caregivers held some moderate to strong concerns towards CPM. These concerns were shown through the Barriers Questionnaire-Taiwan (BQT) survey (ranged 0–5) as follows: disease progression (3.82), side effects (3.29), given as needed (p.r.n) (3.01), tolerance (2.96) and addiction (2.67) [55]. The results also showed some family caregivers reporting their hesitation to administer opioids and to report pain to their patients during the preceding month, because caregivers believed that opioids would cause constipation and harm to patients’ kidneys [55]. Surprisingly, there were also similar concerns towards CPM by caregivers in China, where these concerns were shown as higher or lower in some dimensions; tolerance (3.74), given as needed (p.r.n) (3.51), addiction (3.43), disease progression (3.27) and side effects (3.22) [57]. However, these concerns were lower in the USA, indicating that caregivers in the USA might have a good level of knowledge and positive attitudes towards CPM compared with caregivers in Taiwan and China. For example, the areas of concern for caregivers in the USA were about opioid-related side effects (2.41), fears of addiction (2.35), disease progression (2.28) and tolerance (1.37) [95].

General Public’s Knowledge and Attitudes Towards CPM

The results from 472 general public respondents in the USA who had not been diagnosed with cancer showed that 18% indicated they would avoid seeking care because of concerns about pain associated with cancer treatment. Fifteen percent of the sample agreed or strongly agreed if they had cancer their fear of the disease would make them seek medical care, whereas 9% of them agreed or strongly agreed their concern about cancer pain would lead to avoidance of medical care [51]. The most common key concern among the general public in the USA that would affect them if they had cancer was the “potential for upset to their family”, followed by concern about the “possibility of dying of cancer”. Nearly 50% reported a significant concern about pain resulting from both the cancer and the process of its management [51]. The study also reported that 62% of the general public believed that pain is usually associated with disease progression, 57% thought that cancer patients usually die with a painful death and 50% had significant concerns about opioid side effects including confusion or disorientation, tolerance and opioid addiction [51].

Discussion

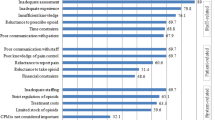

We aimed to systematically review research on the nature and impact of attitudes and knowledge towards CPM. Overall, the results of this review show that a majority of included studies indicated similar attitudinal barriers to effective CPM shared across patients, caregivers, professionals and the public. The barriers most commonly cited by professionals [11, 22, 28, 44, 48, 59, 98, 100], patients and their caregivers [20, 55, 57, 95] and the general public [51] were the fear of poor tolerance, side effects of opioids and drug addiction. However, the most common barriers cited by professionals were contrary to other similar studies, which have suggested that the most important barriers were poor assessment of pain and its management, patient reluctance to take opioids and inadequate staff knowledge of CPM [14, 22, 27, 32, 34, 44, 45, 104]. Furthermore, a previous systematic review by Jacobsen et al. [42] showed that physicians from countries, such as some states in the USA, Australia and Denmark were more often prescribing strong opioids in efficient doses, as they were less concerned about opioid addiction [42]. Nonetheless, their general findings were that physicians consistently reported being concerned about high doses of opioid and the fear of side effects, and these fears were common reasons for reluctance to prescribe adequate amounts of opioids for managing cancer pain [42]. It can thus be suggested that people from different countries have different attitudes and knowledge towards CPM.

One interesting finding was that the results from the majority of studies with cancer patients showed low mean scores on patient’s knowledge and attitudes towards CPM [19, 20, 57, 77]. This result may be explained by the fact that many patients could be reluctant to report their pain to professionals because they have a mistaken belief regarding opioid medication [68]. This finding was also reported by a systematic exploratory review by Jacobsen et al. [43]. Another important finding was that negative attitudes towards morphine were shown by Turkish patients as they continued rejecting morphine for their cancer pain after sessions about opioids were given. The reasons for that were due to fear of addiction, religious reasons and cultural prohibitions [20, 58]. Silbermann and Hassan [88] stated that patients’ response to cancer can differ based on the patients’ beliefs and culture. It has been argued that many patients and their family caregivers viewed opioid medications as a path to death; accordingly, opioid analgesics became their last choice [87]. Despite pain being considered an individual experience, many patients are influenced by their culture, mainly when they are interpreting their pain or accepting the medication of CPM [5, 23, 65]. Therefore, understanding patients’ culture and beliefs can provide the professional with a consideration into how cancer is viewed by the patient [88]. However, professionals can also be influenced by their culture, as it has been reported that cultural beliefs among professionals were one of the most obviously identified barriers towards CPM [80].

Another interesting outcome was that several studies showed physicians had a better level of attitudes and knowledge towards CPM than nurses [22, 32, 44, 45]. There was also a difference between oncologists and surgeons regarding their level of knowledge about cancer pain and its management [33]. It seems possible that these results are due to work experience and training in CPM, as many studies have shown that working with cancer patients’ care and receiving training in CPM can improve professionals’ knowledge and attitudes towards CPM [29, 38, 40, 44, 50, 67, 94, 100].

Most notably, there was a variation between nurses from different countries regarding the level of knowledge and attitudes towards CPM [59]. As could be expected, the variation in knowledge about CPM among those nurses could indicate that morphine is under-prescribed. This view was supported by a systematic review by Oldenmenger et al. [68] who reported that the rates of adherence to opioids for CPM varied from 20 to 95%, with the majority of cancer patients taking their treatments only as needed.

The results also showed that some oncology nurses had an incorrect self-evaluation about their knowledge in CPM [11, 102]. This finding is consistent with that of Omran et al. [70] who also found that Jordanian oncology and non-oncology nurses have a low level of knowledge about CPM. In contrast to earlier findings, several studies indicated that the oncology nurses and doctors achieved higher scores on the knowledge and attitudes surveys (KAS) compared with general nurses and physicians [33, 44, 50, 84, 94]. These positive results could be due to the work experience of professionals in cancer pain settings, as this was reported by McCaffery and Ferrell [59] who stated that nursing staff from countries such as Canada and the USA, which have the longest experience of palliative care units, showed a better level of attitudes and knowledge about CPM than nurses from countries (Japan and Spain) that had palliative care services more recently.

However, it seems that direct experience in oncology units without education and training is not enough to increase professionals’ knowledge about CPM. This view was supported by Bernardi et al. [11] who reported that the years of experience of cancer nurses were not related to pain knowledge scores (p = 0.2). It is possible therefore that education in CPM is the key issue for improving the professionals’ level of knowledge and attitudes towards CPM. A number of authors have considered the effects of educational interventions on professionals’ attitudes and knowledge towards CPM [4, 6, 9, 12, 49, 70, 71]. According to previous systematic reviews of educational interventions aimed to improve CPM in different settings, a significant effect was shown on pain scores, however, the quality of opioid prescription and interference from pain in daily activities was not affected by the majority of interventions [4, 6, 8, 69].

As could be expected, lack of professional education and training in CPM could be one of the most important key barriers for physicians and nurses [34, 39]. Furthermore, this was reported as the highest physician barrier to morphine usage in clinical practice [100]. Another argument was that professionals with cancer patients’ care need professional teaching regarding CPM, which could aid patients in reporting pain and in effectively using the opioids that are prescribed to them [39, 97]. It is also well documented that there is less than optimal pain management for patients with cancer as a result of a lack of professional healthcare education about CPM [18, 60]. Numerous studies have showed that professionals who had experience in palliative care units, receiving training and high level of education in CPM obtained higher scores on the knowledge of cancer pain and its management [45, 49, 70, 71, 94, 100].

Several studies have shown that caregivers had low level of knowledge and attitudes towards CPM [55, 57, 95]. These negative attitudes and inadequate knowledge by caregivers towards opioids could result in attitudinal barriers towards effective CPM [30, 54, 55]. Therefore, it has been argued that it is important to increase caregivers’ ability to participate in CPM and enable them to assess pain and to help their patients take adequate doses of opioids [101]. The correlation between caregivers’ attitudes and their patients’ pain knowledge towards CPM is interesting because patients’ attitudes towards CPM were influenced by their caregivers’ attitudes and the patient’s pain knowledge [57]. Therefore, caregivers should have general awareness and adequate level of knowledge about CPM. It has been argued that caregivers with higher pain management knowledge had significantly fewer barriers to CPM [95].

Results from a study on the general public showed that many people were concern about disease progression and believed that pain was usually associated with this concern. However, some of the public had significant concerns about opioids side effects, tolerance and addiction [51]. Surprisingly, only two studies were found on the general public’s attitudes and knowledge towards CPM and both of articles were published before 2000, consequently updated studies about this area are needed.

Overall, the results of this review have found some evidence that there are negative attitudes and lack of knowledge towards CPM among the four groups included in this review. These findings are consistent with those of recent studies and systematic reviews [12, 13, 20, 26, 37, 79, 80, 96]. Thus, it can be argued that due to these negative attitudes and lack of knowledge towards CPM, the management of cancer pain remains a major problem worldwide, especially in countries within Europe, Africa and Asia [13, 26, 52, 75, 76, 81, 92]. These could be due to lack of education and training about CPM among professionals and lack of general awareness and adequate level of knowledge about CPM among patients, caregivers and the public, as these were stated in all of the included studies. Therefore, healthcare professionals expressed a desire for additional education and training on CPM. A recent systematic review indicated that educational programmes on CPM, including CPM topics in nursing curricula, and training programmes on CPM are the most important factors for enhancing nurses’ knowledge and attitudes towards CPM [12]. It has also been argued that nurses who had received educational programmes on CPM reported significantly higher mean of scores on knowledge about CPM than those who did not have pain education (M = 22 versus M = 20; p = 0.02) [11].

Furthermore, patients, caregivers and the public need general awareness and adequate level of knowledge about CPM. A systematic review reported that providing educational sessions on CPM can improve caregivers’ knowledge and reduce their attitudinal barriers towards CPM [62]. Regarding the general public’s views, it is expected and inevitable that the general public will know very little about CPM unless they have cancer or someone close to them does. Thus, general awareness and adequate level of knowledge about CPM are needed.

Limitations

As only studies published in English were considered within the inclusion criteria, as well as just published studies, it is possible that there are studies that have been published in other languages, also unpublished articles that could have been included in this review. Other limitations could be that even though all included studies used the same design (cross-sectional design), the questionnaires that were used to conduct surveys in this particular area were different and some studies did not state which questionnaire was used or failed to provide information regarding the validity of the tools. Therefore, it was difficult to directly compare studies and the reliability of these included studies in this review could be compromised [74, 90]. In the quality analysis, 15 of the 36 included studies were judged to be only fair quality (see Appendix 3). The reason for a fair quality score instead of a good quality score is that these articles had some methodological limitations. However, almost two-thirds of the included studies, 25 out of the 36 (69.44%), were rated as of good quality. Included studies were from high and low income countries and thus different healthcare systems and cultural beliefs across people form these countries could have affected their attitudes and knowledge towards CPM. Moreover, the possibility of bias could have happened during the reporting of outcomes.

Implications for Clinical Practice

Healthcare professionals should follow specific guidelines for CPM, which have been established by WHO [91] and NICE [10, 66]. Moreover, knowledge and attitudes of professionals need to be improved by intensive training on opioids and educational interventions about cancer pain and its management in order to have effective CPM. Likewise, patients, caregivers and the public will need different approaches to improve general awareness and obtain an adequate level of knowledge about CPM.

Implications for Research

All studies included in this review were quantitative studies. More in-depth understanding of the conceptions and attitudes towards CPM can be provided by qualitative studies [93]. Additionally, qualitative methods could help to identify the factors which can influence the professionals, cancer patients, caregivers and the general public’s attitudes and knowledge towards CPM [93]. Furthermore, more updated studies within CPM are needed to generate more contemporary data in this area.

Conclusions

This systematic review confirms that there are still barriers to effective CPM by professionals, patients, caregivers and the general publics’ lack of knowledge and/or poor attitudes towards CPM, which might result in unalleviated cancer pain. More detailed understanding of how these attitudes arise within different contexts and tailoring educational initiatives to address these are likely to have most impact on improving CPM.

References

Al Khalaileh M, Al Qadire M (2012) Barriers to cancer pain management: Jordanian nurses’ perspectives. Int J Palliat Nurs 18(11):535–540. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2012.18.11.535

Al Qadire M (2012) Patient-related barriers to cancer pain management in Jordan. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 34:S28–S31. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e318249ad34

Al Qadire M, Tubaishat A, Aljezawi MM (2013) Cancer pain in Jordan: prevalence and adequacy of treatment. Int J Palliat Nurs 19(3):125–130. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2013.19.3.125

Allard P, Maunsell E, Labbé J, Dorval M (2001) Educational interventions to improve cancer pain control: a systematic review. J Palliat Med 4(2):191–203. https://doi.org/10.1089/109662101750290227

Alnems A (2012) Oncology nurses’ cultural competence, knowledge, and attitudes toward cancer pain. Published doctoral thesis, San Diego, Ann Arbor, USA

Alvarez MP, Agra Y (2006) Systematic review of educational interventions in palliative care for primary care physicians. Palliat Med 20(7):673–683. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216306071794

American Cancer Society (2011) Global Cancer: facts & figures. American Cancer Society, Atlanta Accessed 11 Oct 2016

Bennett MI, Bagnall A-M, Closs SJ (2009) How effective are patient-based educational interventions in the management of cancer pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis. PAIN® 143(3):192–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2009.01.016

Bennett MI, Flemming K, Closs SJ (2011) Education in cancer pain management. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 5(1):20–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0b013e328342c607

Bennett MI, Graham J, Schmidt-Hansen M, Prettyjohns M, Arnold S (2012) Prescribing strong opioids for pain in adult palliative care: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ:344

Bernardi M, Catania G, Lambert A, Tridello G, Luzzani M (2007) Knowledge and attitudes about cancer pain management: a national survey of Italian oncology nurses. Eur J Oncol Nurs 11(3):272–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2006.09.003

Bouya S, Balouchi A, Maleknejad A, Koochakzai M, AlKhasawneh E, Abdollahimohammad A (2018) Cancer pain management among oncology nurses: knowledge, attitude, related factors, and clinical recommendations: a systematic review. J Cancer Educ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-018-1433-6

Breivik H, Cherny N, Collett B, de Conno F, Filbet M, Foubert AJ, Cohen R, Dow L (2009) Cancer-related pain: a pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann Oncol 20(8):1420–1433. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdp001

Breuer B, Fleishman SB, Cruciani RA, Portenoy RK (2011) Medical oncologists’ attitudes and practice in cancer pain management: a national survey. J Clin Oncol 29(36):4769–4775. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2011.35.0561

Burls A (2009) Evidence-based medicine: what is critical appraisal? Hayward Medical Communications

Butler A, Hall H, Copnell B (2016) A guide to writing a qualitative systematic review protocol to enhance evidence-based practice in nursing and health care. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs 13(3):241–249

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 2009. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: Centre for Reviews & Dissemination, University of York

Chwistek M (2017) Recent advances in understanding and managing cancer pain. F1000Research 6:945–945. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.10817.1

Cohen MZ, Musgrave CF, McGuire DB, Strumpf NE, Munsell MF, Mendoza TR, Gips M (2005) The cancer pain experience of Israeli adults 65 years and older: the influence of pain interference, symptom severity, and knowledge and attitudes on pain and pain control. Support Care Cancer 13(9):708–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-005-0781-z

Colak D, Oguz A, Yazilitas D, Imamoglu IG, Altinbas M (2014) Morphine: patient knowledge and attitudes in the Central Anatolia part of Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 15(12):4983–4988

Cope DK, Zhao Z (2011) Interventional management for cancer pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep 15(4):237–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-011-0206-2

Darawad M, Alnajar MK, Abdalrahim MS, El-Aqoul AM (2017) Cancer pain management at oncology units: comparing knowledge, attitudes and perceived barriers between physicians and nurses. J Cancer Educ 34:366–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-017-1314-4

Davidhizar, R., and J. N. Giger. 2004. A review of the literature on care of clients in pain who are culturally diverse. Int Nurs Rev 51 (1):47–55. doi:doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-7657.2003.00208.x

De Silva, Santha BS, Rolls C (2011) Attitudes, beliefs, and practices of Sri Lankan nurses toward cancer pain management: an ethnographic study. Nurs Health Sci 13(4):419–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00635.x

Dees MK, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Dekkers WJ, Vissers KC, van Weel C (2011) ‘Unbearable suffering’: a qualitative study on the perspectives of patients who request assistance in dying. J Med Ethics 37(12):727–734. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2011.045492

den Beuken-van Everdingen V, Marieke HJ, Hochstenbach LMJ, Joosten EAJ, Tjan-Heijnen VCG, Janssen DJA (2016) Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manag 51(6):1070–1090.e1079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.340

Eftekhar Z, Mohaghegh MA, Yarandi F, Eghtesadi-Araghi P, Moosavi-Jarahi A, Gilani MM, Tabatabeefar M, Toogeh G, Tahmasebi M (2007) Knowledge and attitudes of physicians in Iran with regard to chronic cancer pain. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 8(3):383–386

Elliott TE, Elliott BA (1992) Physician attitudes and beliefs about use of morphine for cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manag 7(3):141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(06)80005-9

Elliott TE, Murray DM, Elliott BA, Braun B, Oken MM, Johnson KM, Post-White J, Lichtblau L (1995) Physician knowledge and attitudes about cancer pain management: a survey from the Minnesota cancer pain project. J Pain Symptom Manag 10(7):494–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/0885-3924(95)00100-D

Elliott BA, Elliott TE, Murray DM, Braun BL, Johnson KM (1996) Patients and family members: the role of knowledge and attitudes in cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manag 12(4):209–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0885-3924(96)00124-8

Ferlay J, Shin H-R, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM (2010) Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 127(12):2893–2917

Furstenberg CT, Ahles TA, Whedon MB, Pierce KL, Dolan M, Roberts L, Silberfarb PM (1998) Knowledge and attitudes of health-care providers toward cancer pain management: a comparison of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists in the state of New Hampshire. J Pain Symptom Manag 15(6):335–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(98)00023-2

Gallagher R, Hawley P, Yeomans W (2004) A survey of cancer pain management knowledge and attitudes of British Columbian physicians. Pain Res Manag 9(4):188–194

Ger L-P, Ho S-T, Wang J-J (2000) Physicians’ knowledge and attitudes toward the use of analgesics for cancer pain management: a survey of two medical centers in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manag 20(5):335–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(00)00207-4

Goldsmith MR, Bankhead CR, Austoker J (2007) Synthesising quantitative and qualitative research in evidence-based patient information. J Epidemiol Community Health 61(3):262–270

Goudas LC, Bloch R, Gialeli-Goudas M, Lau J, Carr DB (2005) The epidemiology of cancer pain. Cancer Investig 23(2):182–190. https://doi.org/10.1081/CNV-50482

Greco MT, Roberto A, Corli O, Deandrea S, Bandieri E, Cavuto S, Apolone G (2014) Quality of cancer pain management: an update of a systematic review of undertreatment of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 32(36):4149–4154

Hollen CJ, Hollen CW, Stolte K (2000) Hospice and hospital oncology unit nurses: a comparative survey of knowledge and attitudes about cancer pain. Oncol Nurs Forum 27(10):1593–1599

Hooten WM, Bruce BK (2011) Beliefs and attitudes about prescribing opioids among healthcare providers seeking continuing medical education. J Opioid Manag 7(6):417–424

Howell D, Butler L, Vincent L, Watt–Watson J, Stearns N (2000) Influencing nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice in cancer pain management. Cancer Nurs 23(1):55–63

Huang H-Y, Wilkie DJ, Chapman CR, Ting L-L (2003) Pain trajectory of Taiwanese with nasopharyngeal carcinoma over the course of radiation therapy. J Pain Symptom Manag 25(3):247–255

Jacobsen, Ramune, Sjogren P, Moldrup C, Christrup L (2007) Physician-related barriers to cancer pain management with opioid analgesics: a systematic review. J Opioid Manag 3(4):207–214

Jacobsen, Ramune, Claus Møldrup, Lona Christrup, and Per Sjøgren. 2009. Patient-related barriers to cancer pain management: a systematic exploratory review. Scand J Caring Sci 23 (1):190–208. doi:doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00601.x.

Jeon YS, Kim HK, Cleeland CS, Wang XS (2007) Clinicians’ practice and attitudes toward cancer pain management in Korea. Support Care Cancer 15(5):463–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-006-0183-x

Jho, Jung H, Kim Y, Kong KA, Kim DH, Choi JY, Nam EJ, Choi JY et al (2014) Knowledge, practices, and perceived barriers regarding cancer pain management among physicians and nurses in Korea: a nationwide multicenter survey. PLOS ONE 9(8):e105900. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105900

Kassa RN, Kassa GM (2014) Nurses’ attitude, practice and barrier s toward cancer pain management, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Cancer Sci Ther 6(12):483–487

Keefe FJ, Abernethy AP, C. Campbell L (2005) Psychological approaches to understanding and treating disease-related pain. Annu Rev Psychol 56:601–630

Kim M-h, Park HG, Park EC, Park K (2011) Attitude and knowledge of physicians about cancer pain management: young doctors of South Korea in their early career. Jpn J Clin Oncol 41(6):783–791. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyr043

Lai Y-H, Chen M-L, Tsai L-Y, Lo L-H, Wei L-L, Hong M-Y, Hsiu L-N, Hsiao-Sheen S-T, Chen S-C, Kao C-C, Huang T-W, Chang S-C, Chen L, Guo S-L (2003) Are nurses prepared to manage cancer pain? A national survey of nurses' knowledge about pain control in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manag 26(5):1016–1025. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(03)00330-0

Larue F, Colleau SM, Fontaine A, Brasseur L (1995) Oncologists and primary care physicians’ attitudes toward pain control and morphine prescribing in france. Cancer 76(11):2375–2382. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19951201)76:11<2375::AID-CNCR2820761129>3.0.CO;2-C

Levin DN, Cleeland CS, Dar R (1985) Public attitudes toward cancer pain. Cancer 56(9):2337–2339. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19851101)56:9<2337::AID-CNCR2820560935>3.0.CO;2-W

Li, Zhang, Aninditha T, Griene B, Francis J, Renato P, Serrie A, Umareddy I, Boisseau S, Hadjiat Y (2018) Burden of cancer pain in developing countries: a narrative literature review. Clin Econ Outcomes Res 10:675–691. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S181192.

Liberati, Alessandro, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000100

Lin C-C (2000) Barriers to the analgesic management of cancer pain: a comparison of attitudes of Taiwanese patients and their family caregivers. Pain 88(1):7–14

Lin C-C, Wang P, Lai Y-L, Lin C-L, Tsai S-L, Chen TT (2000) Identifying attitudinal barriers to family management of cancer pain in palliative care in Taiwan. Palliat Med 14(6):463–470. https://doi.org/10.1191/026921600701536381

Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K (2015) Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthcare 13(3):179–187

Lou F, Shang S (2017) Attitudes towards pain management in hospitalized cancer patients and their influencing factors. Chin J Cancer Res 29(1):75–85. https://doi.org/10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2017.01.09

Lovering S (2006) Cultural attitudes and beliefs about pain. J Transcult Nurs 17(4):389–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659606291546

McCaffery M, Ferrell BR (1995) Nurse’s knowledge about cancer pain: a survey of five countries. J Pain Symptom Manag 10(5):356–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/0885-3924(95)00059-8

McCaffrey M, Ferrell BR (1997) Nurses’ knowledge of pain assessment and management: how much progress have we made? J Pain Symptom Manag 14(3):175–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(97)00170-X

McDarby G, Evans DS, Kiernan R (2017) Patient barriers to adequate analgesia among Irish palliative care patients. J Palliat Care Pediatr

Meeker MA, Finnell D, Othman AK (2011) Family caregivers and cancer pain management: a review. J Fam Nurs 17(1):29–60

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M et al (2017) Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (eds) Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute

Narayan MC (2010) Culture's effects on pain assessment and management. AJN The American Journal of Nursing 110(4):38–47

NICE. 2018. Palliative cancer care - pain. https://cks.nice.org.uk/palliative-cancer-care-pain. Accessed 13 Dec 2018

O’Brien S, Dalton JA, Konsler G, Carlson J (1996) The knowledge and attitudes of experience oncology nurses regarding the management of cancer-related pain. Oncol Nurs Forum 23(3):515–521

Oldenmenger WH, Sillevis Smitt PAE, van Dooren S, Stoter G, van der Rijt CCD (2009) A systematic review on barriers hindering adequate cancer pain management and interventions to reduce them: a critical appraisal. Eur J Cancer 45(8):1370–1380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2009.01.007

Oldenmenger WH, Geerling JI, Mostovaya I, Vissers KCP, de Graeff A, Reyners AKL, van der Linden YM (2018) A systematic review of the effectiveness of patient-based educational interventions to improve cancer-related pain. Cancer Treat Rev 63:96–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.12.005

Omran S, Al Qadire M, Ali NAL, Al Hayek MF (2014) Knowledge and attitudes about pain management: a comparison of oncology and non-oncology Jordanian nurses. Nurs Health 2(4):73–80

Patiraki EI, Papathanassoglou EDE, Tafas C, Akarepi V, Katsaragakis SG, Kampitsi A, Lemonidou C (2006) A randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention on Hellenic nursing staff's knowledge and attitudes on cancer pain management. Eur J Oncol Nurs 10(5):337–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2005.07.006

Pearson A, Robertson-Malt S, Rittenmeyer L (2011) Synthesizing qualitative evidence. Lippincott-Joanna Briggs Institute, Philadelphia

Portenoy RK, Lesage P (1999) Management of cancer pain. Lancet 353(9165):1695–1700

Poudel P, Griffiths R, Wong VW, Arora A, Flack JR, Khoo CL, George A (2018) Oral health knowledge, attitudes and care practices of people with diabetes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 18(1):577

Reis-Pina P, Lawlor PG, Barbosa A (2015) Cancer-related pain management and the optimal use of opioids. Acta Medica Port 28(3):376–381

Reis-Pina P, Lawlor PG, Barbosa A (2018) Moderate to severe cancer pain: are we taking serious action? The opioid prescribing scenario in Portugal. Acta Medica Port 31(9):451–453. https://doi.org/10.20344/amp.10999

Riddell A, Fitch MI (1997) Patients’ knowledge of and attitudes toward the management of cancer pain. Oncol Nurs Forum 24(10):1775–1784

Riesenberg LA, Justice EM (2014) Conducting a successful systematic review of the literature, part 1. Nursing2018 44(4):13–17

Saifan A, Bashayreh I, Batiha A-M, AbuRuz M (2015) Patient– and family caregiver–related barriers to effective cancer pain control. Pain Manag Nurs 16(3):400–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2014.09.007

Saifan AR, Bashayreh IH, Al-Ghabeesh SH, Batiha A-M, Alrimawi I, Al-Saraireh M, Al-Momani MM (2019) Exploring factors among healthcare professionals that inhibit effective pain management in cancer patients. Central Eur J Nurs Midwifery 10(1):967–976. https://doi.org/10.15452/cejnm.2019.10.0003

Saini S, Bhatnagar S (2016) Cancer pain management in developing countries. Indian J Palliat Care 22(4):373–377. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1075.191742

Salim, Nazar, Nijmeh, Al-Attyat, Tuffaha M, Hadan AN, Brant J (2017) Knowledge and attitude of oncology nurses toward cancer pain management: a review. iMedPub J

Shahnazi H, Saryazdi H, Sharifirad G, Hasanzadeh A, Charkazi A, Moodi M (2012) The survey of nurse's knowledge and attitude toward cancer pain management: application of health belief model. J Educ Health Promotion 1:15–15. https://doi.org/10.4103/2277-9531.98573

Shahriary S, Shiryazdi SM, Shiryazdi SA, Arjomandi A, Haghighi F, Vakili FM, Mostafaie N (2015) Oncology nurses knowledge and attitudes regarding cancer pain management. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 16(17):7501–7506

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 349:349. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2015) Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 65(1):5–29

Silbermann M (2011) Current trends in opioid consumption globally and in middle eastern countries. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 33:S1–S5. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e3182121872

Silbermann M, Hassan EA (2011) Cultural perspectives in cancer care: impact of Islamic traditions and practices in middle eastern countries. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 33:S81–S86. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e318230dab6

Stern C, Jordan Z, McArthur A (2014) Developing the review question and inclusion criteria. AJN The American Journal of Nursing 114(4):53–56

The JBI (2016) Critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross sectional studies. http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html. Accessed 6th Sept 2018

The WHO (2018) WHO’s cancer pain ladder for adults. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/. Accessed 3rd Nov 2018

Thinh DHQ, Sriraj W, Mansor M, Tan KH, Irawan C, Kurnianda J, Nguyen YP et al (2018) Patient and physician satisfaction with analgesic treatment: findings from the analgesic treatment for cancer pain in Southeast Asia (ACE) study. Pain Res Manag 2018:8–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2193710

Ung A, Salamonson Y, Hu W, Gallego G (2016) Assessing knowledge, perceptions and attitudes to pain management among medical and nursing students: a review of the literature. Br J Pain 10(1):8–21

Utne I, Småstuen MC, Nyblin U (2018) Pain knowledge and attitudes among nurses in cancer care in Norway. J Cancer Educ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-018-1355-3

Vallerand AH, Collins-Bohler D, Templin T, Hasenau SM (2007) Knowledge of and barriers to pain management in caregivers of cancer patients receiving homecare. Cancer Nurs 30(1):31–37

van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J (2007) Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol 18(9):1437–1449. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdm056

Von Roenn JH, Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, Pandya KJ (1993) Physician attitudes and practice in cancer pain management: a survey from the eastern cooperative oncology group. Ann Intern Med 119(2):121–126. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-119-2-199307150-00005

Wells M, Dryden H, Guild P, Levack P, Farrer K, Mowat P (2001) The knowledge and attitudes of surgical staff towards the use of opioids in cancer pain management: can the hospital palliative care team make a difference? Eur J Cancer Care 10(3):201–211. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2354.2001.00259.x

Wiffen PJ, Wee B, Andrew Moore R (2016) Oral morphine for cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4

Yanjun S, Changli W, Ling W, Woo JC A-l, Sabrina K, Chang L, Lei Z (2010) A survey on physician knowledge and attitudes towards clinical use of morphine for cancer pain treatment in China. Support Care Cancer 18(11):1455–1460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0768-2

Yates P, Aranda S, Edwards H, Nash R (2004) Family caregivers’ experiences and involvement with cancer pain management. J Palliat Care 20(4):287–296

Yildirim YK, Cicek F, Uyar M (2008) Knowledge and attitudes of Turkish oncology nurses about cancer pain management. Pain Manag Nurs 9(1):17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2007.09.002

Zeppetella G, Davies AN (2013) Opioids for the management of breakthrough pain in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (10)

Zhang Q, Yu C, Feng S, Yao W, Shi H, Zhao Y, Wang Y (2015) Physicians’ practice, attitudes toward, and knowledge of cancer pain management in China. Pain Med 16(11):2195–2203. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12819

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks to Sally Dalton for her advice as Library Research Support Advisor and to Dr. Aziza Al-Harbi for her encouragement.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the Ministry of Education in Libya for funding this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 137 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Makhlouf, S.M., Pini, S., Ahmed, S. et al. Managing Pain in People with Cancer—a Systematic Review of the Attitudes and Knowledge of Professionals, Patients, Caregivers and Public. J Canc Educ 35, 214–240 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-01548-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-01548-9