Abstract

There are several competing models of conceptualizing the prostitution industry. One such model, the polymorphous model, posits that sex work contains positive and negative factors and that both must be considered when assessing the consequences of participating in prostitution. This study examines the relationship between participation in prostitution and familial relationships using the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health data. The present study conceptualized participation in prostitution to include both clients and providers. Results indicate that participation in prostitution is not a predictor of parenting satisfaction, relationship satisfaction, or of reporting being the victim of domestic violence. It is, however, associated with a significantly increased chance of perpetrating domestic violence (OR = 2.59). These results highlight the possible power dynamic present in prostitution and how these may influence intimate partner relationships. These dynamics are discussed and their influence on policy is considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

The sex industry has been the focus of substantial research because of its legal, political, social, and public health corollaries (Potterat et al. 2004; Weitzer 2005, 2009, 2012). This industry, as with most others, is comprised of several specialized fields. Weitzer (2010a) suggests that activities involving the “exchange of sexual services, performances, or products for material compensation” (p. 1) including stripping, erotic massage, pornography, phone sex, and prostitution are examples of such fields. The last of which, prostitution, is surrounded by controversy and stigma, tainting all the parties involved including the clients, the managers, and the providers. This is at least partially due to the associated relationship between prostitution and human trafficking, sexually transmitted infections, and violence (Farley 2004; Harrington 2012; Hughes 2004; Overall 1992; Weitzer 2010a). There is growing evidence questioning the veracity and pervasiveness of these associations (Chin and Finckenauer 2012; Crowhurst 2012; Hubbard and Prior 2013; Weitzer 2010b; Weitzer and Ditmore 2010).

The sociological phenomenon of prostitution is often viewed through competing perspectives—or what Weitzer (2010a, 2012) calls paradigms. The oppression paradigm holds that prostitution is inherently and essentially “degrading, immoral, sexist, or harmful” (Weitzer 2010a, p. 4). Conversely, the empowerment paradigm contends that prostitution is validating and places prostitution within an entrepreneurial framework (Bimbi 2007; Schur 1988; Weitzer 2009). Both of these perspectives, however, have a reputation for minimizing research that is contrary to its tenets (Weitzer 2010a, b, 2012). As such, Weitzer (2009) introduces the polymorphous paradigm, which integrates the positions of the oppression and empowerment paradigms and suggests that prostitution is a “constellation of occupational arrangements, power relations, and worker experiences” (p. 215) with both advantageous and dangerous components. The current analysis will utilize the polymorphous paradigm as its theoretical base. The literature review below includes findings that support both the oppression and empowerment paradigms and are presented as objectively as possible. Similarly, the results of the present analysis will be interpreted with Weitzer’s sociological constellation in mind.

Reliable figures regarding the prevalence of prostitution are difficult to obtain because of its clandestine business model (Oselin 2010; Weitzer 2010a). Estimates suggest that roughly 9 % of individuals report having paid for or been paid for sex, with nearly 20 % of men reporting doing so (Monto 2010; Weitzer 2012). With almost one out of ten people participating in prostitution (PIP) as either client or provider and with continued debate on the consequences of PIP, there is need for further understanding of whether and how PIP is associated with personal domains of the involved parties’ lives.

One such domain is that of familial relationships. Examples of this are relationships with spouses, significant others, parents, siblings, and children. There is a paucity of literature available investigating how these relationships may be affected by one’s PIP, save for transient mention in a handful of thorough ethnographic inquiries (e.g., Dewey 2011; Porter and Bonilla 2010). The few extant quantitative studies are almost exclusively concerning the familial relationships of female sex workers, neglecting the customers’ experiences. The exception is studies typically conducted with male attendees of “John Schools,” remediation programs for arrested solicitors. Remediated Johns are more likely to indicate that, because of their PIP, their spouses and children are victims of the prostitution industry and that there are resulting negative effects to their intimate relationships (Kennedy et al. 2004; Wortley et al. 2002). The results of such studies have been criticized for having limited internal and external validity and for not fully capturing the sociological placement of prostitution (Gurd and O’Brien 2013; Weitzer 2005, 2012).

A literature search revealed no quantitative inquiries into the parenting role satisfaction of prostitution participants (PP), clients or providers. The limited qualitative studies available surveyed the parenting experiences of female sex workers and bore two themes regarding those experiences. The first is that, for females with children, sex work is perceived to be a viable means by which to provide for their family—particularly for single mothers. For this latter group, PIP is often considered justified (Dewey 2011; Oselin 2010; Rivers-Moore 2010; Rosen and Venkatesh 2008). The second theme suggests that, in general, female sex workers with children are satisfied with their parenting role, although they also report various deleterious effects of sex work on their parenting success (Dewey 2011; Murphy 2003; Sloss and Harper 2004). Sloss and Harper (2004) found that 88 % of the female sex workers they interviewed had been separated from their children at some point. Erickson et al. (2000) and Rosen and Venkatesh (2008) cited similar trends in stunted parental success among female prostitutes, though fall short of demonstrating any such effect on satisfaction with their parenting role.

Another familial relationship, between PP and their significant others, has been the focus of comparably more empirical attention. Most of the extant literature on the topic is focused on the male customers of female sex workers and is largely thanks to the work of Martin Monto and his colleagues. Roughly half of male clients reported being married (Busch et al. 2002; Monto 2010; Monto and McRee 2005); that number increases to as much as 70 % if steady partners are included (Hughes 2004). Somewhat conversely, Monto and Julka (2009) note that being married is indirectly associated with decreased solicitation of prostitutes. Those that do, however, are significantly more likely to report their marriages as “not too happy” and significantly less likely to report them as “very happy.” Similarly, men without a history of PIP are significantly more likely than PP to be married (Monto and McRee 2005). Furthermore, 41 % of men with a history of PIP report wanting a different kind of sexual experience than they have with their significant other (Monto 2010).

Quantitative research regarding the relationship satisfaction of sex workers is scant; research investigating such for male sex workers is even less abundant. One study (Uy et al. 2004) suggests that, among gay and bisexual male escorts, the consequences of sex work adversely affected their non-professional sex lives. Similarly, the literature on female sex workers’ relationship satisfaction most often examines their sexual satisfaction with non-professional intimate partners. The resulting literature yields inconsistent findings regarding incidence of painful sex, lack of interest, and decreased sexual satisfaction (Munasinghe et al. 2007; Savitz and Rosen 1988; Stebbins 2010). Dewey’s (2011) ethnography highlights female sex workers’ pragmatic challenges navigating non-professional intimate relationships but stops short of addressing satisfaction specifically.

Violence and the potential for violence is a reality for sex workers (Dewey 2011; Hughes 2004; Nixon et al. 2002). This literature specifically examines female workers and male customers. Female PP are vulnerable to violence in their non-professional intimate relationships as well (Nixon et al. 2002; Perdue et al. 2012; Ulibarri et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2012). Additionally, Nixon et al. (2002) found that a notable portion of the female PP they interviewed reported perpetrating domestic violence (DV) in their relationships. Jewkes et al. (2012) reported that men who paid for sex were twice as likely to report having raped a woman and 65 % more likely to report having perpetrated DV in their intimate relationships. Simmons et al. (2008) found similar, though less dramatic, results.

To address the dearth of quantitative analyses of the consequences of PIP on participants’ families, the present study will investigate the association between PIP and two familial relationships using a nationally representative sample. The first of these is the relationship with the children of PP. The second is the relationship with non-professional intimate partners. Recognizing the aforementioned inherent difficulty in analyzing PIP and its associated factors, the present study will support the existing literature by analyzing PIP as a single phenomenon. That is, the possible deleterious effects of PIP on familial relationships will be examined regardless of one’s position as client or provider. The research question being examined is therefore: Does participation in prostitution (PIP) affect the participants’ relationships with their significant others and/or their children? To answer this question, the current study will analyze individuals’ level of parenting role satisfaction, relationship satisfaction, and reporting of DV.

Informed by the prior research, four hypotheses are being tested. First (H1), it is expected that PIP will not be associated with parenting satisfaction after adjusting for demographic and relationship factors. However, a significant association between PIP and relationship satisfaction is expected after adjusting for these same factors (H2). Finally, hypotheses 3 and 4 expect significant associations between PIP and the reporting of being the victim of DV (H3) and of being the perpetrator of DV (H4) after adjustment.

Methods

Participants

Participants were surveyed as part of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (NLSAH) and are available in the public-use data set, which consists of a stratified sample of students from 132 US high schools and middle schools. The study design ensured a representative sample of US schools with respect to demographic factors including location of school, urbanicity, school size, and ethnicity. Wave I of data collection occurred in 1994–1995 and included interviews with more than 90,000 students. Waves II, III, and IV occurred in 1996, 2001–2002, and 2007–2008, respectively. For a detailed explanation of the survey and data collection design see Harris et al. (2009). The data repository removed individual identifiers from the public-use data set to ensure confidentiality. As such, the current study is exempt from institutional review board oversight.

The current analysis used data collected during wave IV of the NLSAH, consisting of 15,701 individuals. The public-use data of wave IV is a random selection of 5,114 participants from the full wave IV sample. The mean age is 29.0 years old (SD = 1.78). The majority of the sample is female (n = 2,761; 54 %), White (n = 3,670; 71.8 %), high school educated (n = 3,046; 59.6 %), and employed (n = 3,361; 65.7 %). Complete demographic data are available in Table 1.

Measures

Participation in Prostitution (PIP)

Item 28 of Section 17 of the NLSAH asked respondents to indicate how frequently they “paid for or have been paid for sex” in the last year. The item contained seven possible choices with 0 = “none” and all subsequent values representing increasing frequency. Participants indicating a 0 on this item (n = 4,287, 83.8 %) are considered non-PP. Participants answering with any other value, thus indicating a frequency of at least once in the last year, represent PP (n = 86, 1.7 %). Of the sample, 741 participants (14.5 %) failed to answer this item and were removed from consequent analysis.

Parenting Role Satisfaction (PS)

Four items in Section 20b of the NLSAH survey asked respondents to indicate their agreement with statements related to their feelings about being a parent (e.g., “I am happy in my role as parent”). Each item was answered using a five-point Likert scale, with 1 = “strongly agree” and 5 = “strongly disagree.” Half the items were positively directed while the remaining two items were negatively directed. The latter were recoded so that, on all items, higher scores indicated greater satisfaction with parenting role. The values of these items were summed, with scores ranging from 4 to 20. Of the sample, 2,538 participants (49.6 %) did not complete one or more of these items—most did so because they had no children—and were removed from analysis of PS. A total of 2,265 participants completed both the PIP measure and the PS measure.

Relationship Satisfaction (RS)

Seven items in Section 17 of the NLSAH survey asked clients to indicate their agreement with statements about their relationship with their current or most recent partner (e.g., “I am/was satisfied with the way we handle our problems and disagreements”). Each item was answered using a five-point Likert scale, with 1 = “strongly agree” and 5 = “strongly disagree.” The items were recoded so that higher scores indicated greater satisfaction. The values were then summed, with scores ranging from 7 to 35. Of the sample, 225 participants (4.4 %) did not complete one or more of these items and were removed from analysis of RS. A total of 4,294 participants completed both the PIP measure and the RS measure.

Victim of Domestic Violence (VDV)

Three items in Section 17 of the NLSAH survey asked clients to indicate the frequency of being the victim of various DV behaviors including being hit, slapped, the target of thrown objects, and/or forced to have unwanted sexual intercourse in the last year of their relationship with their current or most recent partner. All items had eight possible choices with 0 = “never,” 1 = “this has not happened in the past year, but it did happen before then,” and all subsequent values representing increasing frequency within the last year. Participants indicating a 0 or 1 to all three of these items (n = 3,995, 78.1 %) were considered not to have been the victim of DV in the last year of their relationship. Participants answering with any other value on at least one of these items, thus indicating a frequency of at least once in the last year of their relationship (n = 955, 18.7 %), were considered to have been the victim of DV. Of the sample, 164 participants (3.2 %) failed to answer at least one of these items and were removed from analysis of VDV. A total of 4,331 participants completed both the PIP measure and the VDV measure.

Perpetrator of Domestic Violence (PDV)

Three items in Section 17 of the NLSAH survey asked clients to indicate the frequency of perpetrating the same DV behaviors listed in the abovementioned VDV measure. Items were scored and coded in the same fashion as the VDV items. Of the sample, 4,344 (84.9 %) indicated not having perpetrated DV in the last year of their relationship, while 623 (12.2 %) indicated having done so least once. One hundred forty-seven participants (2.9 %) failed to answer at least one of these items and were removed from analysis of PDV. A total of 4,339 participants completed both the PIP measure and the PDV measure.

Controls

The control variables used in the present analysis were largely informed by the results of Palmetto et al. (2013). Their findings suggest that there are individual-specific and relationship-specific variables associated with domestic violence. In the present analysis, eight control variables were separated into these two categories. First, individual-specific factors include gender, educational level, employment status, race, and child abuse history. Of note, wave IV of the NLSAH did not ask participants to identify their race. Instead, one item at the end of the survey asked the interviewer to assess the interviewee’s race. Because of the inexact nature of this item, race was dichotomized into White and non-White for all analyses. Child abuse history included any reporting of verbal, physical, or sexual abuse before the age of 18. Each of these variables was dummy coded to create a reference category.

The second group of control variables, relationship-specific factors, includes relationship length, commitment level, and perceived longevity. Commitment level was measured by use of a four-point Likert scale item asking participants to indicate their level of commitment to their partner with 1 = “completely committed” and all subsequent values representing lesser degrees of commitment. Because of low response rates for some values, this item was dichotomized into “completely committed” and “less than completely committed” for the current analysis. Similarly, perceived longevity was measured by use of a five-point Likert scale item asking participants to indicate the chance that their relationship will be permanent with 3 = “50/50 chance,” lower values indicating greater than 50/50, and higher values indicating less than 50/50. This variable was categorized into these same three groups. Each of these variables, save for relationship length, was dummy coded to create a reference category. Individuals not completing all items of each measure were excluded from analyses involving that variable. All control variable data, including reference category information, are presented in Table 1.

Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21.0. The relationship between the independent variable of PIP and the dependent variables of PS, RS, VDV, and PDV was evaluated. Regression analyses were used in all four cases. Because of the large sample size, an alpha level of α = 0.005 was used to protect against the increased chance of type I error associated with such samples.

For each dependent variable, three separate regressions were conducted, creating three models of each association. Model 1 included PIP only. Model 2 included PIP and the individual-specific controls. The third model included all controls. This was done to assess the strength and stability of the relationship between PIP and the dependent variables when adjusted for the personal context of the participant.

Results

Parenting Satisfaction

Before adjustment, model 1 of the association between PIP and PS was nonsignificant. Model 2 yielded a significant model but did not reveal a significant relationship between PIP and PS. A similar pattern emerged when adjusting for all control variables in model 3, with a significant model and a nonsignificant relationship between PIP and PS. Ultimately, PIP was not significantly associated with PS in any model. These results support H1 and are presented in Table 2.

Relationship Satisfaction

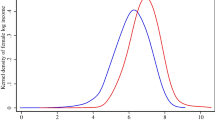

Model 1 assessing the association between PIP and RS was significant. This model indicates that, before adjusting for control variables, PP score an average of 2.94 points lower on the RS measure than non-PP, t(4,293) = −4.66, p < 0.001. This is over half of a standard deviation lower. Model 2, adjusted for individual-specific factors, was also significant and yielded a significant relationship between PIP and RS, t(3,571) = −4.44, p < 0.001. When adjusted for individual-specific factors, PP score an average of 3.19 points lower on the RS measure than non-PP. Again, this is more than half of a standard deviation lower. Adjusting for all control variables in model 3 also produced a significant model. The relationship between PIP and RS, however, was nonsignificant. Contrary to H2, when adjusting for both individual-specific and relationship-specific factors, there is no significant association between PIP and RS. These results are presented in Table 3.

Domestic Violence

The unadjusted model of the relationship between PIP and VDV was significant. In this model, individuals with a history of PIP are 2.56 times more likely than non-PP to report VDV, Wald χ 2(1; n = 4,331) = 16.63, p < 0.001. Adjusting for individual-specific factors also yielded a significant model. However, PIP was no longer significantly associated with VDV in model 2. The same pattern emerged when adjusting for all controls in model 3, with a significant model, and a nonsignificant relationship between PIP and VDV. Although significant in model 1, when adjusting for individual-specific and relationship-specific factors, PIP and VDV were no longer significantly associated. These results do not support H3 and are presented in Table 4.

Model 1, before adjusting for controls, yielded a significant relationship between PIP and PDV. This model suggested that PP are 3.04 times more likely than non-PP to report PDV, Wald χ 2(1; n = 4,339) = 20.77, p < 0.001. When adjusting for individual-specific factors in model 2, both the model and the relationship between PIP and PDV were significant. Model 2 indicated that PP 2.77 times more likely than non-PP to report PDV, Wald χ 2(1; n = 3,609) = 13.05, p < 0.001. Model 3, the fully adjusted model, was also significant. The relationship between PIP and PDV remained significant in this model, with PP 2.59 times more likely than non-PP to report PDV, Wald χ 2(1; n = 3,004) = 8.32, p < 0.005. This is the only analysis wherein PIP remained a significant predictor when adjusting for all controls (see Table 5), ultimately supporting H4.

Discussion

Parenting Satisfaction

PIP was not found to be a predictor of parental satisfaction in the unadjusted or in the adjusted models. This suggests that one’s satisfaction as a parent is unaffected by participating in prostitution. This finding is largely congruent with the earlier noted literature on PP and their children (e.g., Dewey 2011; Murphy 2003; Sloss and Harper 2004). Nonetheless, this still does not address parenting success. As highlighted by Dewey (2011), there is considerable strain on mothers in the sex industry. There are numerous and sizable blockages in the system that prevent these women from being successful parents. One such challenge is, because of the illegality of their profession, the need to operate surreptitiously. This secrecy can prevent female prostitutes from accessing helpful social programs designed to assist mothers (Dewey 2011; Weitzer 2012). With little support and arguably unstable living conditions, female prostitutes are left to make the best decisions regarding the wellbeing their children. One such decision is to have family members raise their children (Erickson et al. 2000; Sloss and Harper 2004). Further research is needed to investigate the relationship between PIP, parenting success, and parenting satisfaction. Research on this topic, however, should be mindful of the potential trap posed by the value-laden concept of parenting success. Female prostitutes giving their children to relatives in order to provide a better chance of a healthy life might not necessarily be considered wholly unsuccessful. Additionally, the results of the current analysis are incongruent with the findings of Kennedy et al. (2004) and Wortley et al. (2002). Their findings—regarding perceived negative familial consequences of a John’s PIP—may have significant moderating influences. Weitzer (2010b, 2012) posits that one such complication is that the surveys used in John School studies are often not anonymous and are sometimes used in determining whether a John’s record is expunged. Future research utilizing an unbiased sample is needed to capture a clearer picture of the possible familial consequences of a John’s PIP.

In both adjusted models, history of child abuse was a significant predictor of parenting satisfaction, indicating that individuals with HCA are less satisfied in their parenting role than are individuals with no HCA. There are two possible explanations for this association. The first, an endogenic process redolent of social learning theory, suggests that persons with HCA may have lacked a model for effective parenting. This can decrease parenting self-efficacy and influence satisfaction with one’s performance. There is a notable volume of research supporting this possibility (Banyard 1997; Herman and Hirschman 1977; Sandberg et al. 2012). The second, a more exogenic process, suggests that parents reflect on the outcomes of their parenting (e.g., their children’s behaviors). Their parenting satisfaction is then a function of these outcomes. Literature supporting this theory indicates that the children of child abuse victims exhibit more problem behaviors (Buist and Janson 2001; Dubowitz et al. 2001) and that a child’s problem behaviors are related to a parent’s satisfaction (Johnston and Mash 1989).

In the fully adjusted model, an individual’s level of commitment to their partner was also a significant predictor of PS. Participants indicating that they are less than fully committed to their partners score lower on the PS measure than do participants indicating full commitment. This association may be the function of interdependence within a family. Those who are less than fully committed to their partner can create unstable family systems and subsystems. This instability is associated with children exhibiting problem behaviors and further family system dysfunction (Cui et al. 2007; Fincham and Hall 2005; Moore and Buehler 2011). As mentioned earlier, children’s problem behaviors are associated with PS.

Ultimately, even with HCA and commitment level serving as significant predictors of PS, the fully adjusted model only accounted for 3 % of the variance in the PS scores. This was unsurprising, as the current analysis included no child-specific variables (e.g., problem behaviors, being separated from children, death of children), which would expectedly account for a significant portion of the variance in PS scores. Future research of PS can build on the results of the present analysis by including both individual-specific (e.g., HCA) and relationship-specific (e.g., commitment level) variables to create a context for findings.

Relationship Satisfaction

In models 1 and 2, PIP predicted decreased relationship satisfaction. In the unadjusted model, PIP was responsible for just 1 % of the RS variance. After adjustment for individual-specific variables, PP are expected to score more than three points lower than non-PP on the RS measure. Ultimately, however, PIP was not a significant predictor of RS in the fully adjusted model. Individuals participating in prostitution are no more or less satisfied in their relationships than are non-PP. This suggests that the relationship between PIP and RS is significantly moderated by the individual’s preexisting perception of their relationship, again implying that the findings of Kennedy et al. (2004) and Wortley et al. (2002) may be incomplete.

The reason for this lack of a significant relationship between PIP and RS is difficult to uncover. A possible explanation is that one’s satisfaction with his/her relationship is not directly related to the perceived durability of the relationship—this ostensibly being the factor collectively accounted for by the relationship-specific variables in the current analysis. As an example, a person may be satisfied with his/her relationship but still perceive the relationship to be temporary and/or trivial. Individuals reporting being uncommitted to their partners are more likely to report extradyadic sexual activity (Buunk and Bakker 1997; Owen et al. 2013), prostitution being a possible means of such. Therefore, sufficiently satisfied individuals may participate in prostitution, confounding the previously assumed association between relationship dissatisfaction and PIP. This theory lacks empirical support, however. There is need for continued research into PP’s motivations to better explain these findings.

Model 3 accounts for 41 % of the variance in RS, a ΔR 2 of 0.37 over model 2. This was anticipated, as a large portion of RS was expected to be attributable to relationship-specific factors. Furthermore, all of the relationship-specific factors are significant predictors of RS. Of the individual-specific factors, sex, history of child abuse, and education level were also significant predictors of RS. Essentially, higher relationship satisfaction was associated with (a) being male, (b) having no HCA, (c) being at least college educated, (d) being completely committed, (e) a shorter relationship, and (f) reporting more than a 50/50 chance that the relationship will be permanent. Perceived longevity possesses the strongest relation with RS (more than three and half times as strong as the next significant predictor). Higher perceived longevity is associated with increased RS, whereas lower perceived longevity predicts lower RS. This finding is not unexpected as RS and perceived longevity/stability are often associated via the interdependence theory. Individuals who are satisfied with the manner in which their relational needs are being met are inclined to remain in those favorable conditions (Drigotas and Rusbult 1992; Levinger 1976; Simpson 1987).

Model 3 of RS accounts for approximately two fifths of the variance in relationship satisfaction. This is a sizeable portion considering that the present analysis did not include variables associated with relational styles (e.g., attachment type, personality type, expectations of relationships) or relationship functioning (e.g., communication, value congruence). The current analysis only offers a transitory perspective of RS and, as such, a full discussion of the results is not possible. Further research that includes these latter elements is needed to further uncover the psychosocial predictors of RS.

Domestic Violence

Victim

The unadjusted model indicated that PIP is a significant predictor of VDV. Notably, this model accounted for less than 1 % of the variance in the probability of VDV. Neither adjusted model yielded a significant relationship between PIP and VDV. This ultimately indicates that PIP is unrelated to VDV when also considering individual- and relationship-specific factors. That which Weitzer (2010a, 2012) describes as the oppression paradigm of prostitution—wherein prostitution is considered inherently violent and the cause of “fundamental harm” (Weitzer 2012, p. 11)—would appear to be at odds with these results. The present analysis calls question to the pervasiveness of the assumed association between PIP and VDV touted by oppression paradigm authors, an assertion suggesting that, for example, women with a history of PIP seek out exploitative intimate relationships (Stebbins 2010). In the aggregate, results suggest that an individual can participate in prostitution without automatically opening up oneself to an increased chance of domestic violence. Subsequent research would be best served by evaluating the relationship between PIP and VDV for providers and for clients within the prostitution industry separately.

The fully adjusted model explained 10 % of the variance in VDV. Risk factors include (a) being male, (b) being non-White, (c) having HCA, (d) less than college educated, (e) being less than fully committed to one’s partner, and (f) reporting lower chances that the relationship will be permanent. Although a full discussion of these results is outside this article’s scope, they are largely congruent with literature on the topic (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2010; Palmetto et al. 2013). The exception to this is finding that women are less likely than men to report VDV; historically, women report higher frequencies of VDV (Tjaden and Thoennes 2000). A possible explanation for this finding in the current analysis is that women are more likely to report in socially desirable ways and do not wish to respond in a way that may reflect poorly on their partner (Bernardi and Guptill 2008). A literature review revealed no quantitative studies examining the general predictors of VDV (i.e., where gender of victim was not assumed). This calls attention to a notable gap in the literature and an area in need of additional research.

Perpetrator

PIP was a significant predictor of PDV in all three models; this is the only instance where this occurred. The unadjusted model accounts for less than 1 % of variance, challenging the pervasiveness of male clients’ aggressive behaviors often alluded to in the literature (Busch et al. 2002; Monto 2010; Monto and Julka 2009; Monto and Mcree 2005; Simmons et al. 2008). However, when considering in the fully adjusted model that PIP more than doubles one’s chance of reporting PDV, these results do indicate a shared characteristic between PIP and PDV. One such possibility may be that of power and control. The concept of a power differential is referenced in sex industry literature (Dominelli 1986; Farley 2004; Murphy 2003; Scoular 2004) and in DV literature (CDC 2010; Karakurt and Cumbie 2012). This theory would posit that individuals participating in prostitution—wherein power and control are evidenced themes—may be more likely to recapitulate those dynamics in their intimate relationships. An alternative, though not mutually exclusive, explanation for this result is related to level of sensation seeking. Sensation seeking has been linked to extradyadic sex and to perpetrating domestic violence (Lalasz and Weigel 2011; Marcus 2008). Increased sensation seeking has been evidenced both by prostitution clients and by providers (Zuckerman 2007). As with VDV, future research can strengthen and clarify the findings of the present analysis by assessing the relationship between PIP and PDV for providers and clients separately.

The fully adjusted model of PDV accounted for 7 % of the variance therein. Higher odds of PDV are associated with (a) PIP, (b) being female, (c) being non-White, (d) having HCA, and (e) being less than fully committed to one’s partner. Being college educated is associated with lower odds of PDV (this association was not found for individuals completing graduate school). Again, a complete discussion of these results is not possible in the current article. They are, however, congruent with PDV literature (CDC 2010; Palmetto et al. 2013; Tjaden and Thoennes 2000). Despite these significant predictors, there remains a sizable portion of variance left unexplained by the model. Building off the current results, future research can include individual trait-oriented measures (e.g., personality, affective regulation) in identifying predictors of PDV.

Limitations

The results of the present study should be interpreted with due consideration of its limitations. The current findings are difficult to generalize, considering that all participants were between the ages of 25 and 34. The age of the sample may also have interacted with some of the independent variables (e.g., relationship length, parenting satisfaction via parental status), making interpretation of these variables fragile. The current analysis was unable to differentiate between same-sex or opposite-sex PIP. Although the literature regarding such is scant, there is some reason to believe that the dynamics of the two may be nuanced. Additionally, ordinal DV measures were collapsed into a dichotomous measure. By doing so, the relationship between PIP and frequency of DV cannot be assessed. A similar limitation results from collapsing across frequency of participation in prostitution. Also, the NLSAH uses three distinct items to measure DV; the present analysis combined these into a single measure. As demonstrated in Simmons et al. (2008), varying types of DV may be more or less associated with PIP than others. By combining DV items, the present study was unable to identify any such differences. Utilizing a single-item measure of PIP is less than ideal because it does not reveal important and specific factors of the sexual exchange (e.g., providers vs. clients, men vs. women, clientele, power imbalances). Though, this practice is not unprecedented and is frequently employed in large national surveys (e.g., Laumann et al. 1994; Smith et al. 2013). Additionally, the wording of the PIP item leaves much open to the participant’s interpretation. He/she is left to define which intimate encounters qualify as paying for or having been paid for sex. This may have its advantages, however, as some who indicated PIP may not have done so if a more conspicuous wording were used (e.g., have you engaged in prostitution). Lastly, this analysis is vulnerable to the same threats to validity as any research conducted with retrospective information. Despite these limitations, the current study represents a significant, if preliminary, attempt to quantify the relationship between participation in prostitution and familial relationships.

Policy Implications

The aggregate of these results informs policy in two ways. First, PIP accounts for less than 1 % of the variance in parenting satisfaction, relationship satisfaction, and DV, even in the only analysis where PIP was a significant independent predictor. This suggests that the relationship between PIP and the negative effects thereof that are discussed in the literature (e.g., Farley 2004; Hughes 2004; Weitzer 2010a, 2012) has significant mediating and/or moderating factors. A sweeping and indiscriminant policy regarding prostitution that is largely punitive and individual-focused, including fines and incarceration for clients and providers (Crowhurst 2012; Sanders 2009; Schur 1988; Weitzer 2012), may therefore be based on an incomplete understanding of these influences. As such, community organizations and policy makers ought to first examine and heavily consider these factors when planning community interventions and/or law.

An example of such moderation is the venue of the sexual exchange. Lever and Dolnick (2010) highlight the differing manifestations of street prostitution and indoor prostitution. Only 2 % of the indoor sample compared to 32 % of the street-based sample reported having a sexual encounter in a car or limo, a locale in which PIP is rightly considered a public nuisance. More than half of the street-based sample reported using drugs before the sexual encounter; only 6 % of the indoor sample did so. There is also an evidenced difference in the intimacy of the encounters between venues. Clients of indoor-based workers are considerably more likely to converse, massage, kiss, and perform oral sex. Weitzer (2012), recognizing that these differences are far from nuanced, calls for a Two-Track approach to prostitution policy. The first track is to decriminalize indoor prostitution, a venue that poses less risk to PP and to the community. There is, of course, a precedent for this in Nevada. The second track is to restructure the response to street prostitution; it would remain illegal and arrested PIP would be entered into assistance programs rather than into legal systems that all too frequently channel them back to the streets.

The second policy implication of the current analysis calls attention to PDV specifically. Though accounting for less than 1 % of variance in reporting perpetrating domestic violence, participating in prostitution does significantly increase one’s chance of doing so. This is undoubtedly a troubling finding to adherents of any paradigm. As suggested above, the evidence points to the power differentials present in both prostitution and in domestic violence. Prostitution providers may, being oppressed by the furtive nature of their work, seek to gain some amount of control in their lives; this is a natural drive of oppressed individuals (Freire 1970). They may seek to do so within the context of their domestic relationships through the psychodynamic process of displacement (Baumeister et al. 1998; Konecni and Doob 1972; Nixon et al. 2002). Prostitution clients may, exploiting the power imbalance from which they benefit, feel entitled to sexual satisfaction (Farley 2004; Schur 1988). This entitlement then generalizes to their domestic partnerships (Jewkes et al. 2012; Simmons et al. 2008).

The current social policy perpetuates the powerlessness of sex workers (Schur 1988; Weitzer 2010a, 2012; Zatz 1997). Alternatively, Schur (1988) proposes more socially contextual approaches to addressing seemingly nonstandard sexual behaviors, including prostitution. The way to address the power differential of prostitution in this manner seems direct: give power to sex workers (Weitzer 2012; Zatz 1997). Whether or not official policy shifts toward decriminalization or legalization of prostitution, community agencies and policy makers should do whatever possible to advocate for the welfare of prostitution providers. Community agencies in particular (e.g., Helping Individual Prostitutes Survive, nd) have served as a safe haven for prostitution providers in this regard. There is a need for policy to follow suit in, even if PIP remains illegal, providing an avenue for prostitution providers to access helpful resources including subsidies. Allowing prostitution providers the same access to housing, health care, child welfare programs, and legal protection (e.g., in the case of reporting a physically violent client) can counter the power imbalance, not to mention offer these providers a sense of worth, social capital, and empowerment. This policy maneuver could substantially mitigate the need for displaced anger among providers, thus reducing PDV. It would also confront clients with a provider who now has legitimacy and legal backing (South African Law Reform Commission 2009; Weitzer 2010a, 2012). This severely threatens the sexual entitlement of the client, reducing its opportunity for generalization to the domestic partnership.

Conclusions

The present analysis did not find a general deleterious effect of participating in prostitution on familial relationships. When adjusting for individual- and relationship-specific factors, a history of participating in prostitution was not a predictor of parenting satisfaction, relationship satisfaction, or being a domestic violence victim. These findings challenge the inherent and pervasive danger that oppression paradigm authors suggest prostitution poses “to marriage, the family, and society’s moral fiber” (Weitzer 2012, p. 10). Policy makers and researchers ought to evaluate the mediating and moderating factors that drive the negative effects of PIP, as there is now evidence that the current generalized policy to PIP is not sensitive to these factors.

The only significant result of the present analysis indicates that PP are more likely than non-PP to perpetrate domestic violence. A possible explanation for this relationship involves the shared theme of power differentials. Attempts to reform prostitution should strongly consider addressing the power imbalance of prostitution facilitated by its clandestineness. In Weitzer’s (2012) best practices for legalizing prostitution, he considers, among other things, the health and safety of those involved in prostitution. By empowering prostitution providers either through decriminalization, legalization, or the formation of support programs, the power differential is spoiled. This, ultimately, secures the health and safety of those involved and, as suggested by the present analysis, of those intimately involved with them. Future research on this topic can, while addressing the limitations of the current study, contribute to the field’s understanding of prostitution and its associated factors, thus supporting an informed process of prostitution policy making.

References

Banyard, V. L. (1997). The impact of childhood sexual abuse and family functioning on four dimensions of women’s later parenting. Child Abuse & Neglect, 21(11), 1095–1107. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00068-9.

Baumeister, R. F., Dale, K., & Sommer, K. L. (1998). Freudian defense mechanisms and empirical findings in modern social psychology: reaction formation, projection, displacement, undoing, isolation, sublimation, and denial. Journal of Personality, 66(6), 1081–1124. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.00043.

Bernardi, R. A., & Guptill, S. T. (2008). Social desirability response bias, gender, and factors influencing organizational commitment: an international study. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(4), 797–809. doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9548-4.

Bimbi, D. S. (2007). Male prostitution: pathology, paradigms and progress in research. Journal of Homosexuality, 53(1–2), 7–35. doi:10.1300/J082v53n01_02.

Buist, A., & Janson, H. (2001). Childhood sexual abuse, parenting, and postpartum depression—a 3-year follow-up study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25, 909–921.

Busch, N., Bell, H., Hotaling, N., & Monto, M. A. (2002). Male customers of prostituted women: exploring perceptions of entitlement to power and control and implications for violent behavior toward women. Violence Against Women, 8(9), 1093–1112. doi:10.1177/107780102401101755.

Buunk, B. P., & Bakker, A. B. (1997). Commitment to the relationship, extradyadic sex, and AIDS prevention behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27(14), 1241–1257. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1997.tb01804.x.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Intimate partner violence: risk and protective factors. (September) http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/riskprotectivefactors.html. Accessed 16 August 2013.

Chin, K., & Finckenauer, J. O. (2012). Selling sex overseas: Chinese women and the realities of prostitution and global sex trafficking. New York: New York University Press.

Crowhurst, I. (2012). Approaches to the regulation and governance of prostitution in contemporary Italy. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: A Journal Of The NSRC, 9(3), 223–232. doi:10.1007/s13178-012-0094-1.

Cui, M., Donnellan, M., & Conger, R. D. (2007). Reciprocal influences between parents’ marital problems and adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1544–1552. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1544.

Dewey, S. (2011). Neon wasteland: on love, motherhood, and sex work in a rust belt town. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Dominelli, L. (1986). The power of the powerless: prostitution and the reinforcement of submissive femininity. The Sociological Review, 34(1), 65–92. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.1986.tb02695.x.

Drigotas, S. M., & Rusbult, C. E. (1992). Should I stay or should I go? A dependence model of breakups. Journal of Personality And Social Psychology, 62(1), 62–87. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.62.1.62.

Dubowitz, H., Black, M. M., Kerr, M. A., Hussey, J. M., Morrel, T. M., Everson, M. D., et al. (2001). Type and timing of mothers’ victimization: effects on mothers and children. Pediatrics, 107, 728–735.

Erickson, P. G., Butters, J., McGillicuddy, P., & Hallgren, A. (2000). Crack and prostitution: gender, myths, and experiences. Journal of Drug Issues, 30(4), 767–788.

Farley, M. (2004). ‘Bad for the body, bad for the heart’: prostitution harms women even if legalized or decriminalized. Violence Against Women, 10(10), 1087–1125. doi:10.1177/1077801204268607.

Fincham, F. D., & Hall, J. H. (2005). Parenting and the marital relationship. In T. Luster & L. Okagaki (Eds.), Parenting: an ecological perspective (2nd ed., pp. 205–233). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder.

Gurd, A., & O’Brien, E. (2013). Californian ‘John Schools’ and the social construction of prostitution. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: A Journal Of The NSRC. doi:10.1007/s13178-013-0117-6.

Harrington, C. (2012). Prostitution policy models and feminist knowledge politics in New Zealand and Sweden. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 9(4), 337–349. doi:10.1007/s13178-012-0083-4.

Harris, K. M., Halpern, C. T., Whitsel, E., Hussey, J., Tabor, J., Entzel, P., & Udry, J. R. (2009). The national longitudinal study of adolescent health: research design. http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design. Accessed 3 April 2013.

Helping Individual Prostitutes Survive. (nd). Mission. www.hips.org. Accessed 15 December 2013.

Herman, J., & Hirschman, L. (1977). Father–daughter incest. Signs, 2(4), 735–756. doi:10.1086/493408.

Hubbard, P., & Prior, J. (2013). Out of sight, out of mind? Prostitution policy and the health, well-being and safety of home-based sex workers. Critical Social Policy, 33(1), 140–159. doi:10.1177/0261018312449807.

Hughes, D.M. (2004). Best practices to addressing the demand side of sex trafficking. http://www.prostitutionetsociete.fr/IMG/pdf/2004huguesbestpracticestoadressdemandside.pdf. Accessed 1 April 2013.

Jewkes, R., Morrell, R., Sikwetiya, Y., Dunkle, K., & Penn-Kekana, L. (2012). Men, prostitution and the provider role: understanding the intersections of economic exchange, sex, crime, and violence in South Africa. PLoS ONE, 7(7), e40821.

Johnston, C., & Mash, E. J. (1989). A measure of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 18(2), 167–175. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp1802_8.

Karakurt, G., & Cumbie, T. (2012). The relationship between egalitarianism, dominance, and violence in intimate relationships. Journal of Family Violence, 27(2), 115–122. doi:10.1007/s10896-011-9408-y.

Kennedy, M., Klein, C., Gorzalka, B. B., & Yuille, J. C. (2004). Attitude change following a diversion program for men who solicit sex. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 40(1–2), 41–60. doi:10.1300/J076v40n01_03.

Konecni, V. J., & Doob, A. N. (1972). Catharsis through displacement of aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 23(3), 379–387. doi:10.1037/h0033164.

Lalasz, C. B., & Weigel, D. J. (2011). Understanding the relationship between gender and extradyadic relations: the mediating role of sensation seeking on intentions to engage in sexual infidelity. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(7), 1079–1083. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.029.

Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: sexual practices in the United States. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lever, J., & Dolnick, D. (2010). Call girls and street prostitutes: selling sex and intimacy. In R. Weitzer (Ed.), Sex for sale: prostitution, pornography, and the sex industry (pp. 187–204). New York: Routledge.

Levinger, G. (1976). A social psychological perspective on marital dissolution. Journal of Social Issues, 32(1), 21–47.

Marcus, R. F. (2008). Fight-seeking motivation in dating partners with an aggressive relationship. The Journal of Social Psychology, 148(3), 261–276. doi:10.3200/SOCP.148.3.261-276.

Monto, M. A. (2010). Prostitutes’ customers: motives and misconceptions. In R. Weitzer (Ed.), Sex for sale: prostitution, pornography, and the sex industry (pp. 233–254). New York: Routledge.

Monto, M. A., & Julka, D. (2009). Conceiving of sex as a commodity: a study of arrested customers of female street prostitutes. Western Criminology Review, 10(1), 1–14.

Monto, M. A., & McRee, N. (2005). A comparison of the male customers of female street prostitutes with national samples of men. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 49(5), 505–529. doi:10.1177/0306624X04272975.

Moore, M. C., & Buehler, C. (2011). Parents’ divorce proneness: the influence of adolescent problem behaviors and parental efficacy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28(5), 634–652. doi:10.1177/0265407510386991.

Munasinghe, T., Hayes, R. D., Hocking, J., Verry, J., & Fairley, C. K. (2007). Prevalence of sexual difficulties among female sex workers and clients attending a sexual health service. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 18(9), 613–616. doi:10.1258/095646207781568592.

Murphy, A. G. (2003). The dialectical gaze: exploring the subject–object tension in the performances of women who strip. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 32(3), 305–335. doi:10.1177/0891241603032003003.

Nixon, K., Tutty, L., Downe, P., Gorkoff, K., & Ursel, J. (2002). The everyday occurrence: violence in the lives of girls exploited through prostitution. Violence Against Women, 8(9), 1016–1043. doi:10.1177/107780102401101728.

Oselin, S. S. (2010). Weighing the consequences of a deviant career: factors leading to an exit from prostitution. Sociological Perspectives, 53(4), 527–550. doi:10.1525/sop.2010.53.4.527.

Overall, C. (1992). What’s wrong with prostitution? Evaluating sex work. Signs, 17(4), 705–724. doi:10.1086/494761.

Owen, J., Rhoades, G. K., & Stanley, S. M. (2013). Sliding versus deciding in relationships: associations with relationship quality, commitment, and infidelity. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 12(2), 135–149. doi:10.1080/15332691.2013.779097.

Palmetto, N., Davidson, L. L., Breitbart, V., & Rickert, V. I. (2013). Predictors of physical intimate partner violence in the lives of young women: victimization, perpetration, and bidirectional violence. Violence and Victims, 28(1), 103–121. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.28.1.103.

Perdue, T. R., Williamson, C., Ventura, L. A., Hairston, T. R., Osborne, L. C., Laux, J. M., et al. (2012). Offenders who are mothers with and without experience in prostitution: differences in historical trauma, current stressors, and physical and mental health differences. Women's Health Issues, 22(2), e195–e200. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2011.08.010.

Porter, J., & Bonilla, L. (2010). The ecology of street prostitution. In R. Weitzer (Ed.), Sex for sale: prostitution, pornography, and the sex industry (pp. 163–186). New York: Routledge.

Potterat, J. J., Brewer, D. D., Muth, S. Q., Rothenberg, R. B., Woodhouse, D. E., Muth, J. B., et al. (2004). Mortality in a long-term open cohort of prostituted women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159(8), 778–785.

Rivers-Moore, M. (2010). But the kids are okay: motherhood, consumption, and sex work in neo-liberal Latin America. The British Journal of Sociology, 61(4), 716–736.

Rosen, E., & Venkatesh, S. (2008). A ‘perversion’ of choice: sex work offers just enough in Chicago’s urban ghetto. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 37(4), 417–441. doi:10.1177/0891241607309879.

Sandberg, J. G., Feldhousen, E. B., & Busby, D. M. (2012). The impact of childhood abuse on women’s and men’s perceived parenting: implications for practitioners. American Journal of Family Therapy, 40(1), 74–91. doi:10.1080/01926187.2011.566827.

Sanders, T. (2009). Kerbcrawler rehabilitation programmes: curing the ‘deviant’ male and reinforcing the ‘respectable’ moral order. Critical Social Policy, 29(1), 77–99. doi:10.1177/0261018308098395.

Savitz, L., & Rosen, L. (1988). The sexuality of prostitutes: Sexual enjoyment reported by ‘streetwalkers’. Journal of Sex Research, 24:200–208. doi:10.1080/00224498809551412.

Schur, E. M. (1988). The Americanization of sex. Philadelphia, PA US: Temple University Press.

Scoular, J. (2004). The ‘subject’ of prostitution: interpreting the discursive, symbolic and material position of sex/work in feminist theory. Feminist Theory, 5(3), 343–355. doi:10.1177/1464700104046983.

Simmons, C. A., Lehmann, P., & Collier-Tenison, S. (2008). Linking male use of the sex industry to controlling behaviors in violent relationships: an exploratory analysis. Violence Against Women, 14(4), 406–417. doi:10.1177/1077801208315066.

Simpson, J. A. (1987). The dissolution of romantic relationships: factors involved in relationship stability and emotional distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(4), 683–692. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.4.683.

Sloss, C. M., & Harper, G. W. (2004). When street sex workers are mothers. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(4), 329–341.

Smith, T. W., Hout, M., & Marsden, P. V. (2013). General Social Surveys 1972–2012: cumulative codebook. Chicago, IL: National Opinion Research Center.

South African Law Reform Commission. (2009). Discussion paper 0001/2009: sexual offenses, adult prostitution. Pretoria: Author.

Stebbins, J. (2010). Implications of sexuality counseling with women who have a history of prostitution. The Family Journal, 18(1), 79–83. doi:10.1177/1066480709356074.

Tjaden, P., & Thoennes, N. (2000). Extent, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence: findings from the national violence against women survey. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice.

Ulibarri, M. D., Strathdee, S. A., Lozada, R., Magis-Rodriguez, C., Amaro, H., O’Campo, P., et al. (2010). Intimate partner violence among female sex workers in two Mexico–U.S. border cities: partner characteristics and HIV risk behaviors as correlates of abuse. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2(4), 318–325. doi:10.1037/a0017500.

Uy, J. M., Parsons, J. T., Bimbi, D. S., Koken, J. A., & Halkitis, P. N. (2004). Gay and bisexual male escorts who advertise on the internet: understanding reasons for and effects of involvement in commercial sex. International Journal of Men’s Health, 3(1), 11–26. doi:10.3149/jmh.0301.11.

Weitzer, R. (2005). New directions in research on prostitution. Crime, Law & Social Change, 43, 211–235.

Weitzer, R. (2009). Sociology of sex work. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 213–234.

Weitzer, R. (2010a). Sex work: paradigms and policies. In R. Weitzer (Ed.), Sex for sale: prostitution, pornography, and the sex industry (pp. 1–44). New York: Routledge.

Weitzer, R. (2010b). The mythology of prostitution: advocacy research and public policy. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 7(1), 15–29. doi:10.1007/s13178-010-0002-5.

Weitzer, R. (2012). Legalizing prostitution. From illicit vice to lawful business. New York/London: New York University Press.

Weitzer, R., & Ditmore, M. (2010). Sex trafficking: facts and fictions. In R. Weitzer (Ed.), Sex for sale: prostitution, pornography, and the sex industry (pp. 325–352). New York: Routledge.

Wortley, S., Fischer, B., & Webster, C. (2002). Vice lessons: a survey of prostitution offenders enrolled in the Toronto John School Diversion Program. Canadian Journal of Criminology, 44(4), 369–402.

Zatz, N. (1997). Sex work/sex act: law, labor and desire in constructions of prostitution. Signs, 22(2), 277–308.

Zhang, C., Li, X., Hong, Y., Chen, Y., Liu, W., & Zhou, Y. (2012). Partner violence and HIV risk among female sex workers in China. AIDS and Behavior, 16(4), 1020–1030. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-9968-0.

Zuckerman, M. (2007). Sensation seeking and risky behavior. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/11555-000.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zeglin, R.J. Participation in Prostitution: Associated Outcomes Within Familial Relationships. Sex Res Soc Policy 11, 50–62 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-013-0143-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-013-0143-4