Abstract

The current study presents a rhythmic music program to acquire some motor skills for children with Down syndrome. The research sample was taken from one of the specialized Down syndrome learning centers for children, and the sample was taken in a random manner. The sample of children consisted of 20 boys and girls and divided into experimental and control groups. The researcher also prepared a list of the appropriate motor skills for these children (walking, running, jumping, throwing), in addition to the motor skills scale to determine the effectiveness of the proposed program. The results were statistically analyzed using the analysis of covariance, where pre-test serving as a covariate. The results indicated an improvement in the performance of all motor activities under study for the children of the experimental group compared to the control group, and this confirms the extent of the positive impact of the musical rhythmic program for these children, which affects the children positively in the performance of their motor.

Résumé

La présente étude présente un programme de musique rythmique pour acquérir certaines habiletés motrices chez les enfants trisomiques. L'échantillon de recherche a été prélevé dans l'un des centres d'apprentissage spécialisés pour les enfants atteints du syndrome de Down, et l'échantillon a été prélevé de manière aléatoire. L'échantillon d'enfants était composé de 20 garçons et filles et divisé en groupes expérimentaux et témoins. La chercheuse a également préparé une liste des habiletés motrices appropriées pour ces enfants (marcher, courir, sauter, lancer), en plus de l'échelle des habiletés motrices pour déterminer l'efficacité du programme proposé. Les résultats ont été analysés statistiquement à l'aide de l'analyse de covariance, le pré-test servant de covariable. Les résultats ont indiqué une amélioration de la performance de toutes les activités motrices à l'étude pour les enfants du groupe expérimental par rapport au groupe témoin, ce qui confirme l'ampleur de l'impact positif du programme rythmique musical pour ces enfants, ce qui affecte positivement les enfants dans les performances de leur moteur.

Resumen

El presente estudio presenta un programa de música rítmica para adquirir algunas habilidades motoras Para niños con síndrome de down. La muestra de la investigación se tomó de uno de los centros de aprendizaje especializados en síndrome de down para niños, y la muestra se tomó de manera aleatoria. La muestra de niños estuvo constituida por 20 niños y niñas y se dividió en grupos experimentales y de control. El investigador también elaboró una lista de las habilidades motoras apropiadas para estos niños (caminar, correr, saltar, lanzar), además de la escala de habilidades motoras para determinar la eficacia del programa propuesto. Los resultados se analizaron estadísticamente mediante el análisis de covarianza, donde el pre test sirvió como covariable. Los resultados indicaron una mejora en el desempeño de todas las actividades motrices en estudio para los niños del grupo experimental en comparación con el grupo control, y esto confirma la magnitud del impacto positivo del programa rítmico musical para estos niños, que afecta positivamente a los niños. en el rendimiento de su motor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Learning in kindergarten is the basis for acquiring different concepts and skills, and the kindergarten stage is the stage of character building and development in all aspects of (mental–cognitive), (physical–motor), (psychological–emotional) and (social). Hearing is one of the first senses that a child uses in communicating with the world around him. This stage is associated with the so-called sensory reception stage. The child can distinguish between sounds in terms of similarity and difference, and through these sounds, he expresses himself in different situations such as laughter and crying. Hearing also develops sensory and motor perception and improves speech and language (Peery et al., 2012). If music has been introduced into the child’s world with its different sounds, movements and colors, then the musical rhythm enters this world with greater force because it is a major component of the music as it is concerned with the temporal split in music. It organizes the musical sounds and divides the times into an orderly division with a meaning that varies in length. The palace is relatively different and also defines the melodies in terms of speed and slowness, and this gives the time value of the absolute for the rhythmic symbols of different forms (Campbell & Scott-Kassner, 2018; Galda et al., 2016). Early childhood specialists believe that the musical nature of children is important in providing experiences that nurture esthetic development and music and movement activities are one of the dimensions of quality early in life. Childhood programs include many music materials accessible to every child and excellent programs provide daily group music activities (Bond, 2015; Harms et al., 2014). Copple and Bredekamp (2009) found that children by nature tend to integrate movement with music, especially in the preschool classroom. Given its importance in children's development and learning, researchers have rigorously studied playing, and many teachers have used it as a classroom tool. Music researchers have observed that music regularly accompanies children’s play because music is part of their culture, and “playing with music” is the most natural form of expression of their existence as musical beings. Hence, play is at the heart of early childhood music, and music teachers design activities that are playful using manipulative, instruments, movements, and musical sounds to engage children. However, scant research has explored the types of play enacted in guided music settings and how children construct musical understanding through play. This article discusses children's play and related theories, illustrates how children “play with music” in the guided music setting, and offers practical applications of play in guided music activities. Children tend to listen to the songs and chants that he praises, as it evokes their emotional feelings through the patterns of behavior that the songs and chants introduce (Williams et al., 2015). Songs have a variety of characteristics that relate to musical concepts (Peery et al., 2012). The different senses are the outlets of knowledge and learning for the kindergarten child, so kindergarten curricula focus on learning with the experience that the child experiences during the practice of various educational activities, and musical activities of different types come from the most important of these activities that are attractive to the child, and that the child accepts Exercise and repeat.

Therefore, the kindergarten stage is considered one of the fertile stages for teaching different skills, because the child at this stage enjoys repetition of doing any work without feeling bored. He also tends to be adventurous, which makes him free to perform the tasks that set him without getting bored, and children learn to move more skillfully while performing their natural movements, such as walking, running and jumping. They also learn stability skills such as how to balance all around and control skills such as throwing and jumping. Children do more than just movement while playing games and it has been proven that musical activities can help them perform basic and non-essential movements, in addition to that movement is an important means of expression used by humans to express their desires and feelings, and it is an innate instinct that they have acquired since birth. In fact, human development is closely related to motor development, and bodily movement is a mental experience, in addition to that movement stimulates the heart, mind and body, and it cannot be taught in the proper sense without the use of physical movements as a means to that in the executive function, and disabled children have shown a deficit in the perception of rhythm (Lesiuk, 2015), suggesting that there may be underlying neural mechanisms involved in self-regulation and rhythm perception. There is strong potential for improving children's rhythm synchronization skills with self-regulatory problems (Slater & Tate, 2018; Srinivasan & Bhat, 2013) and formal music training has also been associated with improved executive and neuronal flexibility. There is a so-called musician’s advantage (George & Koch, 2011; Luo et al., 2012). This feature is thought to result from the improvement of the neural networks involved in rhythm perception and parallel musical perception. Music education from the age of 5 years or younger was found to have better skills in the executive functions of the child’s motor control organs (Joret et al., 2017).

Theoretical Underpinning

There is a need to pay attention to the fine motor coordination of children between the ages of 4–6 years through participation in daily academic activities (Joret et al., 2017). Despite the importance of motor skills, we found that some children at this stage perform these craft tasks and some of these tasks are difficult (Holm et al., 2012). Some studies have confirmed this difficulty in some children while performing some motor tasks, as well as difficulty in motor coordination and control of body movements, which are crucial in performing the daily tasks in the child’s life (Kwan et al., 2013; Mitsiou et al., 2016). Among the motor skills that appear in some children in their difficult performance of transitional and non-transitional movements, and motor skills that are uncoordinated and inaccurate are the ball, running at a regular speed, and skating(American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Some studies confirmed that changing the effects associated with the motor skill stimulates motor performance and helps to learn a new skill (Braun et al., 2009; Wymbs et al., 2016). In contrast, we found that the rhythmic changes during the practice of motor tasks necessarily affect the regularity of timing in the performance of the skill (Maes et al., 2015; Zelaznik et al., 2002). The use of auditory stimulation using rhythmic musical cues has been successfully confirmed by Bella et al. (2015; 2018) in the rehabilitation of motor function in patients with movement disorders of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD), coupling steps with external rhythmic cues for walking speed and stride length. Also, it has been proved that the effects of fluctuation and difference in rhythm during practice may have different effects, as the current study examined the differences in the effect of changes in rhythm during training on timing and skill learning (Caramiaux et al., 2018). The age of walking for a child is important in his motor development, as walking is linked to measures of motor efficiency such as balance, throwing, running and skating (Perreault et al., 2020). It is also associated with various other important development outcomes such as executive functions and important adaptive behaviors (Dammeyer, 2012; Hartshorne et al., 2007). Developing motor skills and a lifestyle are critical to ensuring that children to reach their potential for full participation in school and society (Doyon et al., 2002). And some of the results of recent studies, including the study (Devlin et al., 2019) that uses music, demonstrated the importance of rhythm for poor gait, other motor symptoms and their disturbance, and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease (PD). As confirmed by (Da Silva et al., 2021; Dreu et al., 2012) that using auditory cues with music is beneficial for people with Parkinson’s disease (PD), improving functional balance of cognition, muscle strength, balance and physical activity with an emphasis on enjoyment of music rather than the patient’s existing movement limitations. The effectiveness of educational songs has been reported to complement traditional teaching of subjects such as mathematics, sciences, and English (Kocaba 2009, Crowther, 2012 and Lems, 2018). Developing motor skills and a lifestyle are critical to ensuring that children reach their potential for full participation in school and society(Hales et al., 2017), as well as the use of music in nutritional education programs for children and ad (Kim & Kim, 2012). As confirmed by Skejaa (2014), he stated that linking music therapy with a cognitive intervention program helps children with learning difficulties to move forward in various fields. (Bella et al., 2018) also confirmed that gait disturbances in Parkinson’s disease are partially mitigated by rhythmic auditory cues. This consists in asking patients to walk using a rhythmic auditory stimulus such as a metronome or music. The effect on walking is seen immediately in terms of increased speed and stride length. So, they concluded that rhythmic training programs can have long-term benefits. Therefore, it must be emphasized that the best teachers should be chosen from the teachers who have come forward to teach children in the field of music, in order to teach it in a sound educational manner. (Ballantyne & Grootenboer, 2012), especially with the category of people with special needs, including the category of Down syndrome (DS), as this child is caused by the presence of a partial or complete extra chromosome 21. This increase in genetic material affects the child in various aspects, including physical, mental and social development, and it also causes impairment in the sensory-motor perception of these children in relation to their peers, and there is difficulty about the best ways to identify and design programs that can increase the capabilities of individuals who suffer of DS and their increased participation in physical activity, and the acquisition of motor competence (Latash, 2000). This is confirmed by some studies that children with DS have problems Controlling the motor aspects when performing them. These children need a lot of activities to overcome motor difficulties (Heath et al., 2000). In addition to what some studies have indicated, opportunities to learn motor skills are enjoyable through the use of music and rhythm and stimulate the motor performance of children with DS, which results in their development of their bodies as well as communication with their peers (Virji-Babul et al., 2004). This confirms that training programs that rely on play and motor activities are the most appropriate ways to help the child develop basic motor skills (Kita et al., 2016). The motor activities associated with musical rhythms have the ability to build neural pathways and brain connections linked to self-regulation, which helps the child to keep time while performing motor skills, coinciding with the speed of the audible rhythm (Williams, 2018). Also, there is an emphasis on the ability to keep time by moving to the rhythm of a certain music (Thompson et al., 2015) Therefore, it is important in the current study to find out whether there is a significant difference regarding the performance of some motor skills of children with DS when they are exposed to the rhythmic program of music.

Significance of the Study

Research Importance

The results of the current research may open the way for later studies of new methods and methods to help children with Down syndrome developing different skills in them using different branches of musical activities. It may also benefit the current research in the development of some motor skills of the kindergarten child.

The current research draws the attention of kindergarten workers and specialists to the importance of using musical activities in developing the different skills of a kindergarten child with special needs. Where this study deals with an important axis, which is how to employ musical activities to help a child with Down syndrome in the development of various motor skills, as the use of musical activities is no longer dependent on the entertainment aspect only, but has become an important educational tool to achieve the educational goals of that stage. It also has an important role in developing his esthetic sense, listening skill and language, in addition to its dual composition (melody–rhythm), and this duality has the ability to activate aspects of the child's growth and raise and develop his skill abilities.

The current study provides answers to the following questions:

-

1.

What are the appropriate motor concepts for a child with Down syndrome?

-

2.

What are the musical rhythms used to develop some motor skills for a child with Down syndrome?

The research hypotheses are as follows:

-

1.

There are no statistically significant differences between the average scores of individuals (the experimental group) and the average scores of individuals (the control group) before the application of the musical program based on the group of rhythmic musical melodies in the tribal measurement of the application of the program.

-

2.

There are statistically significant differences between the average scores of the experimental group members (before/after) application of the musical program to develop motor skills in favor of the post-measurement.

The current work aims to:

-

1.

Verifying the effectiveness of musical melodies in developing some motor concepts for children with Down syndrome.

-

2.

Develop some motor concepts for a child with Down syndrome.

-

3.

Preparing a scale of motor skills for a child with Down syndrome.

-

4.

Preparing a group of musical melodies to develop some of the motor skills of a child with Down syndrome.

Method

Participants

Initially, one of the specialized centers for children with Down syndrome in Giza was chosen. The age of the children ranged from 4 to 6 years old, and the research sample was randomly selected and the sample consisted of 20 boys and girls and they were divided into two groups, an experimental group consisting of 7 girls and 3 males, and its average chronological age was 5 years and 7 months, and a group A control group consisting of 6 girls and 4 boys, with an average age of 5 years and 9 month. The research tools (observation card–scale) were firstly applied to the control and experimental groups, then the proposed musical program was applied to the experimental group, and some pictures were taken of them during the application (Fig. 1) and then after the completion of the program application, the research tools were re-applied; then, the difference between the two applications was tested statistically.

Materials

For the purpose of this study, a list of children’s motor skills was identified and presented to specialists to determine the appropriate motor skills for the characteristics of the age sample (Table 1). After that, a measure of motor skills was designed to be applied with the help of a specialist in physical education, in addition to a note card for motor skills. The researcher also prepared and designed a rhythmic music program, and the program included 20 sessions that included a set of motor skills necessary for a child with Down syndrome Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Validity of Research Tools

The research tools were validated by ten new experts in the field of movement education whose role was to confirm whether the content of the scale and note card was accurate and appropriate in terms of language clarity, to check the relevance of each situation, the importance of research objectives, the relevance of the time allotted to the scale, and to present Any additional comments or corrections. The changes they indicated have been incorporated. For example, experts have suggested that some of the motor skills included in the motor scale can be omitted due to difficulty in performing them for a child with Down syndrome, as well as reducing some items on the note card and paraphrasing some statements.

Statistical Analysis

Data collected from the pretests and posttests were analyzed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with posttest as the dependent variable, applied program as independent variable and pretest as the covariate. The homogeneity of variances and regression slopes were verified using Spss program (spss, V. 18, 2009). Only the variances of dependent factor ”throwing” were heterogeneous between two groups, so its data were adjusted by square root transformation. But because of similarity of results before and after transformation, the data were analyzed by the original values.

Study Procedure

The researcher prepared a list of motor skills and presented it to the arbitrators to choose the appropriate ones for these children. After the presentation, the appropriate skills were identified and put into Table 1.

Suggested Music Program

The researcher prepared a kinetic music program that includes a variety of musical activities to help children with Down syndrome to develop their motor skills. The program included 20 sessions and four of them are shown in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Results

Differences Between Scores of the Observation Card

The results in Table 6 showed that the values of two groups got close to each other in pre-test, but in post-test, there was a remarkable (conspicuous) increase in the score in favor of experimental group. In order to control any confounding factor in the analysis, we excluded the effect of the pre-test from the analysis by applying covariance analysis taking the pre-test as a covariate when comparing the results of post-test between both of exp and control group.

The results of covariance showed that the pre-test had not any effect on the results of post-test (p > 0.05), and a significant different in favor of exp group (Tables 7, 8, 9 and 10) was observed for walking, {F(1, 17) = 208.43, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.92; running, F (1, 17) = 151.77, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.89; jumping, F(1, 17) = 128.39, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.89;throwing, F(1, 17) = 125.07, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.87}.

The high value of R squared indicated a high percent of the variance in the response variable can be explained by the explanatory variables for all motor activities under study.

Differences Between Scores After Applying Musical Program

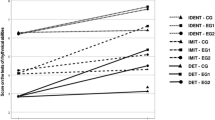

The results in Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5 and Table 11) indicate that no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in the children's mean scores that could be attributed to the pre-test.

The computed (F) value was insignificant for Walking, F(1, 17) = 0.09, p > 0.05; Running, F(1, 17) = 0.01, p > 0.05; Jumping, F(1, 17) = 1.06, p > 0.05; Throwing, F(1, 17) = 2.98, p > 0.05,

This shows the equivalence of the two groups in their abilities before the applying of the music activities.

On the contrary, there were statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) at post-test between the mean scores of children who were exposed music activity (experimental group) and those who were not exposed to musical activity (control group) in motor skills (Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4).

The computed (F) value was significant for Walking, {F(1, 17) = 163.32, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.91; Running, F(1, 17) = 173.8, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.90; Jumping, F(1, 17) = 102.94, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.84; Throwing, F(1, 17) = 125.94, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.87}.

The high value of R2 indicated a high percent of the variance in the response variable can be explained by the explanatory variables for all motor activities under study.

In other words, scores were significantly increased from pre-test to post-test of all Motor skills.

Discussion

This study examined the effect of the rhythm of the music used on the balance, level of motor skills, coordination and discipline in the skilled performance of children with Down syndrome, confirmed by (Hilgenbrink et al., 2020) that physical education teachers usually do not know how to use the rhythm of music in teaching the motor skills of a child with Down syndrome, and found (Heibach & Liebermann, 2013; Haibach-Beach et al, 2020) that children with Down syndrome have limited balance ability, which may affect performance in motor skills such as walking and running. Therefore, these teachers need to be trained in how to use music to develop the motor skills of this class. Referenced (Lieberman et al., 2012; Sorrell & Stratton, 2019) show that children with Down syndrome have limited physical education skills as part of the daily educational program despite evidence of the importance of motor training for them. This was confirmed by (Houston Wilson, 2017; Hilgenbrink et al., 2020). A multidisciplinary team that must be properly prepared and equipped to ensure that children with Down syndrome have the best approaches to improving their competence.

The proposed kinetic music program was applied to the research sample. Two groups were selected, one experimental and the other a control group. This program has been shown to be effective in developing and improving dynamic balance, coordination and flexibility in children with Down syndrome. Where it was found that there is a significant difference in the levels of motor performance in the selected skills which are walking, running, jumping and throwing. Therefore, (Foster et al., 2020) emphasized the urgent need for early intervention for children with Down syndrome which in turn leads to improved motor skills, leading to enhanced proprioception and motor balance development.

Research Recommendations

-

1.

Paying attention to the preparation of teachers specialized in the field of people with special needs.

-

2.

Focusing on musical activities in all its branches (singing–playing–listening and tasting–musical games–musical story) and employing them to help people with special needs.

-

3.

The necessity of holding training courses for special education teachers in the field of musical activities to develop their practical performance.

Conclusion

Children with Down syndrome suffer from many cases of difficulty in motor performance that affect their ability and to develop motor competence at a rate similar to their peers who develop normally. The well-documented benefits of music and the effectiveness of rhythm in helping to master movement, as the musician is characterized by a wide scope in the field of music therapy. The application of the program rhythmic music to them, and the results of the research showed a remarkable improvement in those skills, as the sample children participated in interacting with the rhythm of music in a successful manner, and therefore, this remarkable development will be reflected in the rest of their motor skills, so the movement difficulties of children with Down syndrome need appropriate early intervention.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). APA.

Ballantyne, J., & Grootenboer, P. (2012). Exploring relationships between teacher identities and disciplinarity. International Journal of Music Education Practice, 30(4), 368e381.

Bella, S. D., Benoit, C. E., Farrugia, N., Schwartz, M., & Kotz, S. A. (2015). Effects of musically cued gait training in Parkinson’s disease: Beyond a motor benefit. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1337(1), 77–85.

Bella, S. D., Dotov, D., Bardy, B., & de Cock, V. C. (2018a). Individualization of music-based rhythmic auditory cueing in Parkinson’s disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1423(1), 308–317.

Bond, V. L. (2015). Sounds to share: The state of music education in three Reggio Emilia—inspired North American preschools. Journal of Research in Music Education, 62(4), 462–484.

Braun, D. A., Aertsen, A., Wolpert, D. M., & Mehring, C. (2009). Motor task variation induces structural learning. Current Biology, 19(4), 352–357.

Campbell, P. S., & Scott-Kassner, C. (2018). Music in childhood enhanced: From preschool through the elementary grades. Cengage Learning.

Caramiaux, B., Bevilacqua, F., Wanderley, M. M., & Palmer, C. (2018). Dissociable effects of practice variability on learning motor and timingskills. PLoS ONE, 13(3), e0193580. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193580

Copple, C., & Bredekamp, S. (Eds). (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8. 3 rd ed.

Crowther, G. (2012). Using science songs to enhance learning: An interdisciplinary approach. CBE Life Sciences Education, 11, 26–30.

Da Silva, L. K., Brito, T. S. S., de Souza, L. A. P. S., & Luvizutto, G. J. (2021). Music-based physical therapy in Parkinson’s disease: An approach based on international classification of functioning, disability and health. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies, 26, 524–529.

Dammeyer, J. (2012). Development and characteristics of children with usher syndrome and CHARGE syndrome. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 76(9), 1292–1296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.05.021

De Dreu, M. J., van der Wilk, A. S., Poppe, E., Kwakkel, G., & van Wegen, E. E. (2012). Rehabilitation, exercise therapy and music in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis of the effects of music-based movement therapy on walking ability, balance and quality of life. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 18(Suppl. 1), S114eS119.

Devlin, K., Alshaikh, J. T., & Pantelyat, A. (2019). Music therapy and music-based in-terventions for movement disorders. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 19(11), 83.

Doyon, J., Song, A. W., Karni, A., Lalonde, F., Adams, M. M., & Ungerleider, L. G. (2002). Experience-dependent changes in cerebellar contributions to motor sequence learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(2), 1017–1022. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.022615199

Foster, E., Silliman-French, L., & Grenier, M. (2020). Parents’perceptions of constraints impacting the development of walking in children with CHARGE syndrome. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 45(3), 196–211.

Galda, L., Liang, L. A., & Cullinan, B. E. (2016). Literature and the child (8th ed.). Wadsworth Publishing.

George, E. M., & Coch, D. (2011). Music training and working memory: An ERP study. Neuropsychologia, 49, 1083–1094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.02.001

Haibach, P., & Lieberman, L. J. (2013). Balance and the self-efficacy of balance in children with CHARGE syndrome. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, 107(4), 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X1310700406

Haibach-Beach, P. S., Perreault, M., Lieberman, L., & Foster, E. (2020). Independent walking and balance in children with CHARGE syndrome. British Journal of Visual Impairment. https://doi.org/10.1177/0264619620946068

Hales, C. M., Carroll, M. D., Fryar, C. D., & Ogden, C. L. (2017). Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db288.pdf

Harms, T., Clifford, R. M., & Cryer, D. (2014). Early childhood environment rating scale (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Hartshorne, T. S., Nicholas, J., Grialou, T. L., & Russ, J. M. (2007). Executive function in CHARGE syndrome. Child Neuropsychology, 13(4), 333–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297040600850944

Heath, M., Elliott, D., Weeks, D. J., & Chua, R. (2000). A functional systems approach to movement pathology in persons with DS. In D. J. Weeks, R. Chua, & D. Elliott (Eds.), Perceptual motor behavior in Down syndrome (pp. 305–317). Human Kinetics.

Hilgenbrinck, L., Cavanaugh, L. K., & Lieberman, L. J. (2020). Gross motor assessment results and placement in physical education of five students with CHARGE syndrome. Palaestra, 34(3), 27–36.

Holm, I., Tveter, A. T., Aulie, V. S., & Stuge, B. (2012). High intra-and inter-rater chance variation of the movement assessment battery for children 2, age band 2. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34, 795–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.11.002

Houston-Wilson, C. (2017). Infants and toddlers. In J. P. Winnick & D. Porretta (Eds.), Adapted physical education and sport (6th ed., pp. 407–420). Human Kinetics.

Spss Inc. Released 2009 PASW statistics for windows, version 18 Chicaco: Spss Inc.

Joret, M. E., Germeys, F., & Gidron, Y. (2017). Cognitive inhibitory control in children following early childhood music education. Musicae Scientiae, 21, 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/10298649166655477

Kim, B. H., Kim, M., & Lee, Y. (2012). The effect of a nutritional education program on the nutritional status of elderly patients in a long-term care hospital in Jeollanamdo province: Health behavior, dietary behavior, nutrition risk level and nutrient intake. Nutrition Research and Practice, 6, 35–44.

Kita, Y., Suzuki, K., & Hirata, S. (2016). Applicability of the movement assessment battery for children-second edition to Japanese children: A study of the age band 2. Brain & Development, 38, 706–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2016.02.012

Kocaba, A. (2009). Using songs in mathematics instruction: Results from pilot application. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1, 538–543.

KwanM, Y., Cairney, J., & Hay, J. A. (2013). Understanding physical activity and motivations for children with developmental coordination disorder: An investigation using the theory of planned behavior. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(11), 3691–3698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.08.020

Latash, M. L. (2000). Motor coordination in Down syndrome: The role of adaptive changes. In D. J. Weeks, R. Chua, & D. Elliott (Eds.), Perceptual motor behavior in Down syndrome (pp. 199–221). Human Kinetics.

Lems, K. (2018). New ideas for teaching English using songs and music. English Teaching Forum, 56(1), 14–21.

Lesiuk, T. (2015). Music perception ability of children with executive function deficits. Psychology of Music, 43, 530–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735614522681

Lieberman, L. J., Haibach, P., & Schedlin, H. (2012). Physical education and children with CHARGE syndrome: Research to practice. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, 106(2), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X1210600205

Luo, C., Guo, Z. W., Lai, Y. X., Liao, W., Liu, Q., & Kendrick Li, H. (2012). Musical training induces functional plasticity in perceptual and motor networks: Insights from resting-state fMRI. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036568

Maes, P.-J., Wanderley, M. M., & Palmer, C. (2015). The role of working memory in the temporal control of discrete and continuous movements. Experimental Brain Research, 233(1), 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-014-4108-5

Mitsiou, M., Giagazoglou, P., & Sidiropoulou, M. (2016). Static balance ability in children with developmental coordination disorder. European Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 11(1), 17–23.

Peery, J. C., Peery, I. W., & Draper, T. W. (Eds.). (2012). Music and child development. Springer Science & Business Media.

Perreault, M., Haibach-Beach, P. S., Foster, E., & Lieberman, L. (2020). Relationship between motor skills, balance, and physical activity in children with CHARGE syndrome. Journal of Visual Impairments & Blindness, 114(4), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X20939469

Skejaa, E. (2014). The impact of cognitive intervention program and music therapy in learning disabilities, university of tirana, faculty of social sciences. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 159, 605–609.

Slater, J. L., & Tate, M. C. (2018). Timing deficits in ADHD: Insights from the neuroscience of musical rhythm. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncom.2018.00051

Sorrell, J., & Stratton, K. K. (2019). Physical education accommodations: Is your child receiving assistance? [Poster presentation]. In The 14th International CHARGE Syndrome Professionals Day Conference

Srinivasan, S. M., & Bhat, A. N. (2013). A review of “music and movement” therapies for children with autism: Embodied interventions for multisystem development. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 7, 22.

Thompson, E., White-Schwoch, T., Tierney, A., & Kraus, N. (2015). Beat synchronization across the lifespan: Intersection of development and musical experience. PLoS ONE, 10, e0128839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128839

Virji-Babul, N., Jobling, A., Nichols, D., & Purves, L. (2004). Speak the dance: Results of a pilot study and language program in children with Down syndrome. Presentation at the 8th World Congress, Singapore.

Williams, K. E. (2018). Moving to the beat: Using music, rhythm, and movement to enhance self-regulation in early childhood classrooms. International Journal of Early Childhood, 50, 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-018-0215-y

Williams, K. E., Barrett, M. S., Welch, G. F., Abad, V., & Broughton, M. (2015). Associations between early shared music activities in the home and later child outcomes: Findings from the longitudinal study of Australian children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 31, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.01.004

Wymbs, N. F., Bastian, A. J., & Celnik, P. A. (2016). Motor skills are strengthened through reconsolidation. Current Biology, 26(3), 338–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.066

Zelaznik, H. N., Spencer, R., & Ivry, R. B. (2002). Dissociation of explicit and implicit timing in repetitive tapping and drawing movements. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 28(3), 575.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. All author certifies that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. The author has no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mazeed, H.M. A Program for Developing Some Motor Skills for Down Syndrome Children Using Music. IJEC 55, 47–68 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-022-00338-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-022-00338-7