Abstract

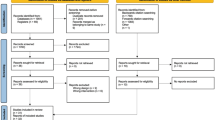

Integrating physical activity (PA) counseling in routine clinical practice remains a challenge. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the implementation and effectiveness of a pragmatic strategy aimed to improve physician PA counseling and patient PA. An effectiveness-implementation type-2 hybrid design was used to evaluate a 3-h training (i.e., implementation strategy-IS) to increase physician use of the 5-As (assess, advise, agree, assist, arrange) for PA counseling (i.e., clinical intervention-CI) and to determine if the CI improved patient PA. Patients of trained and untrained physicians reported on PA and quality of life pre-post intervention. Medical charts (N = 1700) were examined to assess the proportion of trained physicians that used the 5-As. The RE-AIM framework informed our evaluation. 305/322 of eligible physicians participated in the IS (M age = 40 years, 52% women) and 683/730 of eligible patients in the CI (M age = 49 years, 77% women). The IS was adopted by all state regions and cost ~ $20 Mexican pesos (US$1) per provider trained. Physician adoption of any of the 5-As improved from pre- to post-training (43 vs. 52%, p < .01), with significant increases in the use of assessment (43 vs. 52%), advising (25 vs. 39%), and assisting with barrier resolution (7 vs. 15%), but not in collaborative goal setting (13 vs. 17%) or arranging for follow-up (1 vs. 1%). Patient PA and quality of life did not improve. The IS intervention was delivered with high fidelity at a low cost, but appears to be insufficient to lead to broad adoption of the CI.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. 2009. Available at http://www.Who.Int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/globalhealthrisks_report_full.Pdf. Accessed 9 Sept 2017.

Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012; 280(9838):219–29.

Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012; 380(9838):247–57.

Gutiérrez JP, Rivera-Dommarco J, Shamah-Levy T, Villalpando-Hernández S, Franco A, Cuevas-Nasu L, et al. Encuesta nacional de salud y nutrición Resultados nacionales. Cuernavaca, méxico: Instituto nacional de salud pública; 2012.

Global burden of disease collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2015; 385(9963):117–71.

Reis RS, Salvo D, Ogilvie D, Lambert EV, Goenka S, Brownson RC. Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet. 2016; 388(10051):1337–48.

Vuori IM, Lavie CJ, Blair SN. Physical activity promotion in the health care system. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013; 88(12):1446–61.

Garrett S, Elley CR, Rose SB, O'Dea D, Lawton BA, Dowell AC. Are physical activity interventions in primary care and the community cost-effective? A systematic review of the evidence. Br J Gen Pract. 2011; 61(584):e125–33.

Orrow G, Kinmonth A-L, Sanderson S, Sutton S. Effectiveness of physical activity promotion based in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2012; 344:e1389–9.

Sanchez A, Bully P, Martinez C, Grandes G. Effectiveness of physical activity promotion interventions in primary care: a review of reviews. Prev Med. 2015; 76:S56–67.

Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: a evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002; 22(4):267–84.

Estabrooks P, Glasgow R, Dzewaltowski D. Physical activity promotion through primary care. J Am Med Assoc. 2003; 289(22):2913–6.

Galaviz KI, Jauregui E, Fabrigar L, Latimer-Cheung A, Lopez y Taylor J, Lévesque L. Physical activity prescription among Mexican physicians: a structural equation model testing the theory of planned behavior. Int J Clin Pract. 2015; 69(3):375–83.

Scott S, Albrecht L, O'Leary K, Ball G, Hartling L, Hofmeyer A, et al. Systematic review of knowledge translation strategies in the allied health professions. Implement Sci. 2012; 7(1):70.

Godin G, Belanger-Gravel A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Healthcare professionals’ intentions and behaviours: a systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implement Sci. 2008; 3(1):36.

Perkins MB, Jensen PS, Jaccard J, Gollwitzer P, Oettingen G, Pappadopulos E, et al. Applying theory-driven approaches to understanding and modifying clinicians’ behavior: what do we know? Psychiatr Serv. 2007; 58(3):342–8.

Zilberman J, Cicco L, Woronko E, Vainstein N, Sczcygiel V, Ghigi R, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors. A multicenter uncontrolled follow-up study. Argentine J Cardiol. 2012; 80(2):130–6.

Eckstrom E, Hickam D, Lessler D, Buchner D. Changing physician practice of physical activity counseling. J Gen Intern Med. 1999; 14(6):376–8.

Marcus BH, Goldstein MG, Jette A, Simkin-Silverman L, Pinto BM, Milan F, et al. Training physicians to conduct physical activity counseling. Prev Med. 1997; 26(3):382–8.

Aittasalo M, Miilunpalo S, Ståhl T, Kukkonen-Harjula K. From innovation to practice: initiation, implementation and evaluation of a physician-based physical activity promotion programme in Finland. Health Promot Int. 2007; 22(1):19–27.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211.

Sassen B, Kok G, Vanhees L. Predictors of healthcare professionals’ intention and behaviour to encourage physical activity in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. BMC Public Health. 2011; 11:246.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Censo de poblacion y vivienda 2010. Available at http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/proyectos/ccpv/2010/. Accessed 9 Sept 2017.

Frenk J, Gomez O, Knaul FM. The democratization of health in Mexico: financial innovations for universal coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2009; 87:542–8.

Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012; 50(3):217–26.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the re-aim framework. Am J Public Health. 1999; 89(9):1322–7.

Estabrooks PA, Gyurcsik NC. Evaluating the impact of behavioral interventions that target physical activity: issues of generalizability and public health. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2003; 4(1):41–55.

Antikainen I, Ellis R. A re-aim evaluation of theory-based physical activity interventions. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2011; 33(2):198–214.

Galaviz KI, Harden SM, Smith E, Blackman KCA, Berrey LM, Mama SK, et al. Physical activity promotion in Latin American populations: a systematic review on issues of internal and external validity. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014; 11:77–7.

Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008; 27(3):379–87.

World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. 2010. Avalialbe at http://www.Who.Int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_recommendations/en/. Accessed 9 Sept 2017.

Almeida FA, Smith-Ray RL, Van Den Berg R, Schriener P, Gonzales M, Onda P, et al. Utilizing a simple stimulus control strategy to increase physician referrals for physical activity promotion. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2005; 27:505–14.

Petrella RJ, Lattanzio CN, Overend TJ. Physical activity counseling and prescription among Canadian primary care physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167(16):1774–81.

Ramsay C, Thomas R, Croal B, Grimshaw J, Eccles M. Using the theory of planned behaviour as a process evaluation tool in randomised trials of knowledge translation strategies: a case study from UK primary care. Implement Sci. 2010; 5(1):71.

Carroll JK, Yancey AK, Spring B, Figueroa-Moseley C, Mohr DC, Mustian KM, et al. What are successful recruitment and retention strategies for underserved populations? Examining physical activity interventions in primary care and community settings. Transl Behav Med. 2011; 1(2):234–51.

Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985; 10(3):141–6.

Brislin R. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 1970; 1(3):185–216.

Horner-Johnson W, Krahn G, Andresen E, Hall T, Rehabilitation R, M Training Center Expert Panel on Health Status. Developing summary scores of health-related quality of life for a population-based survey. Public Health Rep. 2009; 124(1):103–10.

Lee KJ, Carlin JB. Multiple imputation for missing data: fully conditional specification versus multivariate normal imputation. Am J Epidemiol. 2010; 171(5):624–32.

Carroll JK, Antognoli E, Flocke SA. Evaluation of physical activity counseling in primary care using direct observation of the 5As. Ann Fam Med. 2011; 9(5):416–22.

Hillsdon M, Thorogood M, White I, Foster C. Advising people to take more exercise is ineffective: a randomized controlled trial of physical activity promotion in primary care. Int J Epidemiol. 2002; 31(4):808–15.

Fortier M, Hogg W, O’Sullivan T, Blanchard C, Sigal R, Reid R, et al. Impact of integrating a physical activity counsellor into the primary health care team: Physical activity and health outcomes of the physical activity counselling randomized controlled trial. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011; 36(4):503–14.

Coleman KJ, Ngor E, Reynolds K, Quinn VP, Koebnick C, Young DR, et al. Initial validation of an exercise “vital sign” in electronic medical records. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012; 44(11):2071–6.

Patrick K, Pratt M, Sallis RE. The healthcare sector’s role in the U.S. national physical activity plan. J Phys Act Health. 2009; 6(2):S211–9.

Acknowledgments

This study was part of the Pausa Laboral Project, a collaboration among researchers from Queen’s University, the University of Guadalajara, Arizona State University, Emory University, the University of Nebraska Medical Center, the Metropolitan Autonomous University, and the Jalisco Secretary of Health. We thank the Jalisco Secretary of Health for providing support and access to conduct this study. We also thank the physicians and patients from the Jalisco Secretary of Health who participated in this study. Finally, we thank the dietitians and physical activity experts who helped with data collection (in alphabetical order): María Bueno Rea, Claudia Brizuela Rosas, Karla Castellanos Díaz, Karen Cortez García, José de Jesús Contreras, Guillermo Cuevas Aguilar, Ricardo Echauri Baltazar, Sandra Espinolla Magallón, Silvia García González, Raúl García Robles, José Gómez Gamboa, Mara Guzmán Gómez, Dorian Lizandro Velazco, Mauricio Madrid Hernández, Carolina Márquez Muñoz, Gloria Montes López, Liliana Muñoz Moreno, Yareli Orozco Loyola, Denise Ivette Páez, Viviana Pérez Bernal, Mercedes Robles Ramos, José Luis Saavedra Gómez, Fabiola Sánchez Rodríguez, Isabel Tovar, Gibran Urbano, and Carmen Villalvazo Reina.

Funding

This work was conducted with the financial support of a grant (CIHR GIR 127075) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Institute of Population and Public Health, the CIHR Institute of Cancer Research and the Public Health Agency of Canada–—Chronic Disease Prevention Branch.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The other authors declare that they have no financial or other conflict of interests. Edtna Jauregui works for the Jalisco Secretary of Health and receives salary from that institution.

Additional information

Implications

Practice: These findings can have an impact on researchers by providing evidence of how an effectiveness-implementation hybrid study design can be used to blend clinical effectiveness trial and implementation research elements to speed the translation of research findings into routine practice.

Policy: These findings can have an impact on practitioners by informing their physical activity promotion practices and describing an evidence-based tool they can use in their practice.

Research: These findings can have an impact on policy makers by informing current physician training strategies the Secretary of Health in Jalisco is implementing.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 13.4 kb)

About this article

Cite this article

Galaviz, K.I., Estabrooks, P.A., Ulloa, E.J. et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of physician counseling to promote physical activity in Mexico: an effectiveness-implementation hybrid study. Behav. Med. Pract. Policy Res. 7, 731–740 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-017-0524-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-017-0524-y