Abstract

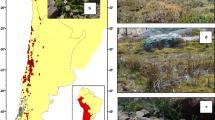

Setchellanthus caeruleus, which has disjunct populations in the north of the Chihuahuan Desert and in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán valley, was selected to understand the evolutionary history of plants in this desert and its southerly relicts. This species constitutes the monotypic family Setchellanthaceae, which forms part of a group of plants that produce mustard-oil glucosides or glucosinolates. Molecular phylogenetic analyses based on DNA plastid sequences of plants of S. caeruleus from both areas, including representative taxa of the order Brassicales, were carried out to estimate the time of origin of the family (based on matK + rcbL) and divergence of populations (based on psbI-K, trnh-psbA, trnL-trnF). In addition, comparative ecological niche modelling was performed to detect if climate variables vary significantly in northern and southern populations. Analyses revealed that Setchellanthaceae is an ancient lineage that originated between 78 and 112 Mya during the mid-late Cretaceous—much earlier than the formation of the Chihuahuan Desert. The molecular data matrix displayed a few indel events as the only differences of plastid DNA sequences between northern and southern populations. It is suggested that due to climate changes in this desert in the Pliocene, populations of Setchellanthus remained in the Sierra de Jimulco and in Cuicatlán, in climatically stable locations. Ecological niche models of northern populations predict niches of southern populations and identity niche tests indicate that there are no differences in their ecological niches.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Axelrod, D. I. (1958). Evolution of the madro-tertiary geoflora. The Botanical Review, 24, 433–509.

Axelrod, D. I. (1979). Desert vegetation its age and origin. In J. R. Goodin & D. K. Northington (Eds.), Arid land plant resources, proceedings of the international arid lands conference on plant resources (pp. 1–72). Lubbock: Texas Tech University, International Center for Arid and Semi-Arid Land Studies.

Becker, H. F. (1961). Oligocene plants from the upper Ruby River Basin, southwestern Montana. Geological Society of America Memoir, 82, 1–127.

Beilstein, M. A., Nagalingum, N. S., Clements, M. D., Manchester, S. R., & Mathews, S. (2010). Dated molecular phylogenetics indicate a Miocene origin for Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 107, 18724–18728.

Brenner, G. J. (1996). Evidence of the earliest stage of angiosperm pollen evolution: A paleoequatorial section from Israel. In D. W. Taylor & L. J. Hickey (Eds.), Flowering plant origin, evolution and phylogeny (pp. 91–115). New York: Chapman and Hall.

Campbell, V., & Lapointe, F.-J. (2009). The use and validity of composite taxa in phylogenetic analysis. Systematic Biology, 58, 560–572.

Carlquist, S., & Miller, R. B. (1999). Vegetative anatomy and relationships of Setchellanthus caeruleus (Setchellanthaceae). Taxon, 48, 289–302.

Carvalho, F. A., & Renner, S. S. (2012). A dated phylogeny of the papaya family (Caricaceae) reveals the crop's closest relatives and the family's biogeographic history. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 65, 46–53.

CONABIO. (2000). Regiones Terrestres Prioritarias. Mapa. México: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Couvreur, T. L. P., Franzke, A., Al-Shebaz, I. A., Bakker, F. T., Koch, M. A., & Mummenhoff, K. (2010). Molecular phylogenetics, temporal diversification, and principles of evolution of the mustard family (Brassicaceae). Molecular Biology and Evolution, 27, 55–71.

Dávila, P., Arizmendi, M. D., Valiente-Banuet, A., Villaseñor, J. L., Casas, A., & Lira, R. (2002). Biological diversity in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley, Mexico. Biodiversity and Conservation, 11, 421–442.

Doyle, J. J., & Doyle, J. L. (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure from small quantities of fresh leaf tissues. Phytochemistry Bulletin, 19, 11–15.

Drummond, A. J., & Rambaut, A. (2007). BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 7, 214.

Dunning, L. T., & Savolainen, V. (2010). Broad-scale amplification of matK for DNA barcoding plants, a technical note. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 164, 1–9.

Edgar, R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research, 32, 1792–1797.

Elias, S. A., Van Devender, T. R., & de Baca, R. (1995). Insect fossil evidence of late glacial and Holocene environments in the Bolson de Mapimí, Chihuahuan Desert, Mexico: comparisons with the Palaeobotanical record. Palaios, 10, 454–464.

Ferrari, L., Orozco-Esquivel, T., Manea, V., & Manea, M. (2012). The dynamic history of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt and the Mexico subduction zone. Tectonophysics, 522, 122–149.

Gandolfo, M. A., Nixon, K. C., & Crepet, W. L. (1998). A new fossil flower from the Turonian of New Jersey: Dressiantha bicarpellata gen et sp. nov. (Capparales). American Journal of Botany, 85, 964–974.

Glor, R., & Warren, D. (2010). Testing ecological explanations for biogeographic boundaries. Evolution, 65, 673–683.

Goloboff, P. A, Farris, J. S. & Nixon, K. N. (2003). TNT: Tree Analysis Using New Technology, Version 1.0. Program and Documentation. Available from: http://www.zmuc.dk/public/phylogeny/tnt.

Graham, C. H., Ron, S. R., Santos, J. C., Schneider, C. J., & Moritz, C. (2004). Integrating phylogenetics and environmental niche models to explore speciation mechanisms in dendrobatid frogs. Evolution, 58, 1781–1793.

Hafner, D. J., & Riddle, B. R. (2005). Mammalian phylogeography and evolutionary history in northern Mexico's deserts. In J.-L. E. Cartron, G. Ceballos, & R. S. Fleger (Eds.), Biodiversity, ecosystems and conservation in Northern Mexico (pp. 225–245). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hall, T. A. (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series, 41, 95–98.

Hawlitschek, O., Porch, N., Hendrich, L., & Balke, M. (2011). Ecological niche modelling and nDNA sequencing support a new, morphologically cryptic beetle species unveiled by DNA barcoding. PLoS One, 6, e16662.

Henrickson, J. (2012). Systematics of Lindleya (Rosaceae: Maloideae). Journal of Botanical Research of the Institute of Texas, 6, 341–360.

Henrickson, J., & Johnston, M. C. (1986). Vegetation and community types of the Chihuahuan Desert. In J. C. Barlow, A. M. Powell, & B. N. Timmermann (Eds.), The second symposium on resources of the Chihuahuan Desert region, United States and Mexico (pp. 20–39). Alpine: Chihuahuan Desert Research Institute.

Hernández, H. M., & Gómez-Hinostrosa, C. (2011). Areas of endemism of Cactaceae and the effectiveness of the protected area network in the Chihuahuan Desert. Oxyx, 45, 191–200.

Hernández, P. A., Graham, C. H., Master, L. L., & Albert, D. L. (2006). The effect of sample size and species characteristics on performance of different species distribution modelling methods. Ecography, 29, 773–785.

Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G., & Jarvis, A. (2005). Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology, 25, 1965–1978.

Ho, S. Y. W., & Philips, M. J. (2009). Accounting for calibration uncertainty in phylogenetic estimation of evolutionary divergence times. Systematic Biology, 58, 367–380.

Iglesias, A., Wilf, P., Johnson, K. R., Zamuner, A. B., Cuneo, N. R., Matheos, S. D., & Singer, B. S. (2007). A Paleocene lowland macroflora from Patagonia reveals significantly greater richness than North American analogs. Geology, 35, 947–950.

Iltis, H. H. (1999). Setchellanthaceae (Capparales), a new family for a relictual, glucosinolate-producing endemic of Mexican deserts. Taxon, 48, 257–275.

Jaeger, E. C. (1957). North American Deserts (pp. 33–43). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Jezkova, T., Jaeger, J. R., Marshall, Z. L., & Riddle, B. R. (2009). Pleistocene impacts on the phylogeography of the desert pocketmouse (Chaetodipus penicillatus). Journal of Mammalogy, 90, 306–320.

Karol, K. G., Rodman, J. E., Conty, E., & Sytsma, K. J. (1999). Nucleotide sequence of rbcL and phylogenetic relationships of Setchellanthus caeruleus. Taxon, 48, 303–315.

Kozak, K. H., & Wiens, J. J. (2006). Does niche conservatism promote speciation? A case study in North American salamanders. Evolution, 60, 2604–2621.

Krings, A. (2000). A phytogeographical characterization of the vine flora of the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts. Journal of Biogeography, 27, 1311–1319.

Lahaye, R., van der Bank, M., Maurin, O., Duthoit, S., & Savolainen, V. (2008). A DNA barcode for the flora of the Kruger National Park (South Africa). South African Journal of Botany, 74, 370–371.

Lobo, J. M., Jiménez-Valverde, A., & Real, R. (2008). AUC: a misleading measure of the performance of predictive distribution models. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 17, 145–151.

Loera, I., Sosa, V., & Ickert-Bond, S. M. (2012). Diversification in North American arid lands: niche conservatism, divergence and expansion of habitat explain speciation in the genus Ephedra. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 65, 437–450.

Magallón, S., & Castillo, A. (2009). Angiosperm diversification through time. American Journal of Botany, 96, 349–365.

Magallón, S., & Sanderson, M. J. (2001). Absolute diversification rates in angiosperm clades. Evolution, 55, 1762–1780.

Manchester, S. R. (1999). Biogeographical relationships of North American Tertiary floras. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 86, 472–522.

Manchester, S., & O’Leary, E. (2010). Phylogenetic distribution and identification of fin-winged fruits. The Botanical Review, 76, 1–82.

McCain, C. M. (2003). North American desert rodents: a test of the mid-domain effect in species richness. Journal of Mammalogy, 84, 967–980.

Méndez-Larios, I., Villaseñor, J. L., Lira, R., Morrone, J. J., Dávila, P., & Ortiz, E. (2005). Toward the identification of a core zone in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán biosphere reserve, Mexico, based on a parsimony analysis of endemicity of flowering plant species. Interciencia, 30, 267–274.

Miller, R. R. (1977). Composition and derivation of the native fish fauna of the Chihuahuan Desert region. In R. H. Wauer & D. H. Riskind (Eds.), Transactions of the Symposium on the biological resources of the Chihuahuan Desert region, United States and Mexico (pp. 365–382). Alpine: Sul Ross State University.

Mithen, R., Bennett, R., & Márquez, J. (2010). Glucosinolate biochemical diversity and innovation in Brassicales. Phytochemistry, 71, 2074–2086.

Moore, M. J., & Jansen, R. K. (2006). Molecular evidence for the age, origin, and evolutionary history of the American desert plant genus Tiquilia (Boraginaceae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 39, 668–687.

Morafka, D. J. (1977). A biogeographical analysis of the Chihuahuan Desert through its herpetofauna. Biogeographica, 1–317.

Müller, K. (2005). SeqState - primer design and sequence statistics for phylogenetic DNA data sets. Applied Bioinformatics, 4, 65–69.

Nylander, J. A. A. (2004). MrModeltest v2. Program distributed by the author. Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University.

Pearson, R. G., Raxworthy, C. J., Nakamura, M., & Peterson, A. T. (2007). Predicting species distributions from small numbers of occurrence records: a test case using cryptic geckos in Madagascar. Journal of Biogeography, 34, 102–117.

Phillips, S. J., & Dudik, M. (2008). Modeling of species distributions with MaxEnt: new extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography, 31, 161–175.

Phillips, S. J., Anderson, R. P., & Schapire, R. E. (2006). Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecological Modeling, 190, 231–259.

Riddle, B. R., & Hafner, D. J. (2006). A step-wise approach to integrating phylogeographic and phylogenetic biogeographic perspectives on the history of a core North American warm deserts biota. Journal of Arid Environments, 66, 435–461.

Rodman, J. E., Soltis, P. S., Soltis, D. E., Sytsma, K. J., & Karol, K. G. (1998). Parallel evolution of glucosinolate biosynthesis inferred from congruent nuclear and plastid gene phylogenies. American Journal of Botany, 85, 997–1006.

Ronquist, F., & Huelsenbeck, J. P. (2003). MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics, 19, 1572–1574.

Ronse de Craene, L. P., & Hanson, E. (2006). The systematic relationships of glucosinolate-producing plants and related families: a cladistic investigation based on morphological and molecular characters. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 151, 453–494.

Ruiz-Sanchez, E., Rodríguez-Gómez, F., & Sosa, V. (2012). Refugia and geographic barriers of populations of the desert poppy, Hunnemannia fumariifolia (Papaveraceae). Organisms, Diversity and Evolution, 12, 133–143.

Savolainen, V., Chase, M. W., Fay, M. F., van der Bank, M., Powell, M., Albach, D. C., Weston, P., Backlund, A., Johnson, S. A., Pintaud, J.-C., Cameron, K. M., Sheanan, M. C., Sotis, P. S., & Soltis, D. E. (2000). Phylogeny of the eudicots: a nearly complete familial analysis based on rbcL gene sequences. Kew Bulletin, 55, 257–309.

Schmidt, R. H. (1986). Chihuahuan climate. In J. C. Barlow, A. M. Powell, & B. N. Timmermann (Eds.), Chihuahuan Desert - U. S. and Mexico (Vol. 2, pp. 40–63). Alpine: Sul Ross State University.

Schoener, T. W. (1968). Anolis lizards of Bimini: resource partitioning in a complex fauna. Ecology, 49, 704–726.

Selmeier, A. (2005). Capparidoxylon holleisii nov. spec., a silicified Capparis (Capparaceae) wood with insect coprolites from the Neogene of southern Germany. Zitteliana, 45, 199–209.

Shaw, J., Lickey, E. B., Beck, J. T., Farmer, S. B., Liu, W. S., Miller, J., Siripun, K. C., Winder, C. T., Schilling, E. E., & Smal, R. L. (2005). The tortoise and the hare II: relative utility of 21 noncoding chloroplast DNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses. American Journal of Botany, 92, 142–166.

Shreve, F. (1942). The desert vegetation of North America. The Botanical Review, 4, 195–246.

Simmons, M. P., & Ochoterena, H. (2000). Gaps as characters in sequence based phylogenetic analyses. Systematic Biology, 49, 369–381.

Sosa, V., & De-Nova, A. (2012). Endemic angiosperm lineages in Mexico: hotspots for conservation. Acta Botanica Mexicana, 100, 293–315.

Stamatakis, A. (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: Maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics, 22, 2688–2690.

Tobe, H., Carlquist, S., & Iltis, H. H. (1999). Anatomy and relationships of Setchellanthus caeruleus (Setchellanthaceae). Taxon, 48, 277–283.

Tomb, A. S. (1999). Pollen morphology and relationships of Setchellanthus caeruleus. Taxon, 48, 285–288.

Van Devender, T. R. (1990). Late Quaternary vegetation and climate of the Sonoran Desert, United Staes and Mexico. In J. L. Betancourt, T. R. Van Devender, & P. S. Martin (Eds.), Packrat middens: the last 40,000 years of biotic change (pp. 134–163). Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Wang, H., Moore, M. J., Soltis, P. S., Bell, C. D., Brockington, S. F., Alexandre, R., Davis, C. C., Latvis, M., Manchester, S. R., & Soltis, D. E. (2009). Rosid radiation and the rapid rise of angiosperm-dominated forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 106, 3853–3858.

Warren, D. L., Glor, R. E., & Turelli, M. (2008). Environmental niche equivalency versus conservatism: quantitative approaches to niche evolution. Evolution, 62, 2868–2883.

Warren, D. L., Glor, E. R., & Turelli, M. (2010). ENMTools: a toolbox for comparative studies of environmental niche models. Ecography, 33, 607–611.

Wikström, N., Savolainen, V., & Chase, M. W. (2001). Evolution of the angiosperms: calibrating the family tree. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 268, 2211–2220.

Wilgenbusch, J. C., Warren, D. L., & Swofford, D. L. (2004). AWTY: a system for graphical exploration of MCMC convergence in Bayesian phylogenetics. Bioinformatics, 24, 581–583.

Wilson, J. S., & Pitts, J. P. (2010a). Phylogeographic analysis of the nocturnal velvet ant genus Dilophotopsis (Hymenoptera: Mutillidae) provides insights into diversification in the Neartic deserts. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 101, 360–375.

Wilson, J. S., & Pitts, J. P. (2010b). Illuminating the lack of consensus among descriptions of earth history data in the North American deserts: a resource for biologists. Progress in Physical Geography, 34, 419–441.

Wilson, J. S., & Pitts, J. P. (2012). Identifying Pleistocene refugia in North American cold deserts using phylogeographic analyses and ecological niche modelling. Diversity and Distributions, 18, 1139–1152.

Wolfe, J. A. (1976). Stratigraphic distribution of some pollen types from the Campanian and lower Maastrichtian rocks (Upper Cretaceous) of the middle Atlantic states. United States Geological Survey Professional Papers, 977, 1–18.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Israel Loera, Diego Angulo, and Etelvina Gándara for assistance in the field. We also thank Arith Pérez and Cristina Bárcenas for their help in the laboratory. We thank Tom Wendt for his help for accessing specimens in TEX. We thank the curators of ENCB, IEB, MEXU, and XAL for allowing us to access their collections. Laboratory and fieldwork was supported by a grant from CONACyT (106060) to V.S. Part of this study constituted fulfilment of the Bachelor's thesis requirement of W.C. at Universidad Veracruzana.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 606 kb)

Appendices

Appendix 1

Species considered in phylogenetic analyses for Setchellanthaceae and their GenBank accession numbers (matK and rbcL).

Malvales: Anisoptera marginata AJ581409, Y15144. Bixa orellana FM179929, AF022128. Bombax buonopozense AY321171, AF022118. Daphne bholua FM179927, AF022132. Dombeya spectabilis AY321173, AY082354. Halimium lasianthum GQ281698, GQ281670. Helianthemum scopulicola DQ092970, Y15141. Hibiscus syriacus EF207270, AY328174. Luehea seemannii GQ982036, GQ981791. Peddiea africana FJ572800, AJ745176. Sterculia tragacantha AY321178, FJ976172. Thymelaea hirsuta EU002191, Y15151. Huertales: Gerrardina foliosa FM179924, AY757086. Tapiscia sinensis EU002190, AF206825. Brassicales: Bretschneidera sinensis AY483220, M95753. Batis maritima AY483219, M88341. Aethionema grandiflora AF144354, AY167983. Alliaria petiolata AF144363, FJ395597. Arabidopsis lyrata AF144342, XM2888312. Arabis glabra AF144333, DQ310542. Armoracia rusticana FN597648, AF020323. Brassica napus AB354273, AF267640. Cakile maritima GQ424577, AY167981. Capsella bursa-pastoris HQ619802, FN594844. Cardamine flexuosa AB248011, D88905. Cardamine hirsuta HQ619803, HQ619739. Cochlearia danica AF174531, FN594827. Descurainia sophia GQ424581, FN594838. Erophila verna HQ619804, HQ619740. Erysimum handel-mazzettii DQ409262, AY167980. Halimolobos jaegeri DQ406763, FN594846. Heliophila variabilis GQ424588, AM234933. Iberis amara GQ424589, FN594828. Isatis tinctoria AB354278, FN594830. Lepidium perfoliatum DQ406766, GQ436651. Nasturtium officinale AY483225, AF020325. Neslia paniculata DQ406767, DQ310541. Raphanus raphanistrum AB354265, GQ184382. Rorippa islandica DQ406770, AF020328. Sisymbrium irio AF144366, AY167982. Noccaea cochleariformis GQ424598, FN594826. Thlaspi arvense AF144360, FN594829. Vella pseudocytisus GQ248209, GQ248705. Apophyllum anomalum AY483227, AY483264. Cadaba virgata EU371753, AM234931. Capparis spinosa AY491650, AY167985. Crataeva palmeri AY483229, AY483265. Maerua kirkii AY483229, AY483265. Wislizenia refracta AY483230, AY483266. Forchhammeria trifoliata AY483235, AY483271. Carica papaya AY483245, AY483277. Cylicomorpha parviflora AY042564, M95671. Jacaratia digitata AY461575, AF405244. Cleome hassleriana AY461574, AF405245. Cleome pilosa AY491649, M95755. Cleome viridiflora AY483231, AY483267. Podandrogyne decipiens AY483232, AY483268. Polanisia dodecandra EU371815, AY483269. Gyrostemon thesioides AY483234, AY167984. Tersonia cyathiflora FJ212199, FJ212210. Koeberlinia spinosa AY483238, L22441. Floerkea proserpinacoides AY483222, L14600. Moringa oleifera EU002178, L12679. Pentadiplandra brazzeana AY483223, L11359. Caylusea latifolia AY483239, U38533. Ochradenus baccatus GQ891209, GQ891229. Oligomeris linifolia GQ891194, GQ891210. Reseda lutea AY483240, AY483272. Reseda luteola AY483241, AY483273. Reseda crystallina FJ212206, FJ212219. Sesamoides purpurascens FJ212200, FJ212212. Setchellanthus caeruleus FJ212208, KC778754; FJ212221, KC778756; Tovaria pendula AY483242, M95758. Tropaeolum majus AY483224, AB043534.

Appendix II

Specimens of Setchellanthus caeruleus utilized for morphological observations and for ecological niche models. Specimens utilized for molecular analyses and their GenBank accession numbers are also indicated.

Northern populations

Coahuila: I. M. Johnston 11478 (XAL), Coahuila, Jimulco, 103.2’W, 25.183’N; J. Valdés Reyna, H. H. Iltis, K. Karol & E. Blanco 149963 (TEX), Coahuila, Torreón, 103.64’ W, 25.51’N; M. Engleman (XAL). Durango: Durango, Lerdo, 103.64’W, 25.52’N; Durango: D. S. Correll & I. M.Johnston 20012, 149968 (TEX), Durango, Lerdo, 103.65’W, 25.21’N; H. H. Iltis & A. Lasseigne, 100 (XAL) Durango, Lerdo, 103.71’W, 25.43’N; H. H.Iltis & A. Lasseigne, 149964 (TEX) Durango, Lerdo, 103.71’W, 25.45’N; E. Gándara 3046 (XAL), Durango, Mapimí, 25.67’W, 103.87’N; E. Gándara 3050 (XAL), Durango, Lerdo, 25.43’W, 103.70’W; H. Sánchez-Mejorada 2576 (MEXU), km 101 carretera Gómez-Palacio a Ceballos; J. Henrickson 23145 (TEX), Durango, ca. 16 air miles SW of Torreón, upper road to Microondas Sapioris 103.45'W, 25.26'N. DNA plastid sequences (psbA-trnH, trnL-trnF and psbI-psbK). Population 1: E. Gándara 3046 (XAL) (KC778733 - KC778736; KC778769 - KC778772; KC867730 - KC8737) Population 2: Gándara 3050 (XAL) (KC867721 - KC867728; KC86772 - KC867719; KC778749 - KC778752).

Southern populations

Oaxaca: C. A. Purpus 3400 (UC), Mesa de Coscomate; F. González-Medrano F-1552 (MEXU), Oaxaca, Cuicatlán, 96.99’W, 17.81’N; J. G. Sánchez-Ken 220 (MEXU), Oaxaca, Cuicatlán, 97.01’W, 17.81’N; F. González-Medrano F-1168 (MEXU), Oaxaca, Teotitlán, 97.06’W, 18.09’N; P11767 (XAL), 97.48’W, 18.31’N; A. Valiente Banuet 900 (MEXU), 97.48’W, 18.32’N; 149967 (TEX), Puebla, San José Miahuatlán, 97.22’W, 18.17’N; M. Castañeda-Zárate & W. Colorado-Durán 432–444 (MEXU), Puebla, Zapotitlán de las Salinas, 18.31’W, 97.47’N; J. Rzedowski 33229 (MEXU), 17 km SW de Tehuacán, carretera a Huajuapan de León; J. Panero (3465) (MEXU) ca. 5 km from Axusco. DNA plastid sequences (trnH-psbA, trnL-trnF and psbI-psbK): Population 1: M. Castañeda-Zárate & W.B. Colorado-Durán 432–436 (MEXU) (KC778722 - KC778726; KC778758 - KC778762; KC778738 - KC778743). Population 2: M. Castañeda-Zárate & W. B. Colorado-Durán 437–444, (KC778727 - KC778730; KC778763 - KC778767; KC778744 - KC778748) A. Valiente Banuet 900 (MEXU) (KC78731 - KC8732; KC8767 - KC778768).

Carica papaya N. P. Moreno 101 (XAL), Xalapa, Veracruz (KC867738, KC867729, KC867720).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hernández-Hernández, T., Colorado, W.B. & Sosa, V. Molecular evidence for the origin and evolutionary history of the rare American desert monotypic family Setchellanthaceae. Org Divers Evol 13, 485–496 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13127-013-0136-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13127-013-0136-4