Abstract

Objectives

Nonattachment has been found to be a potentially important mental quality in mitigating psychological distress and promoting well-being across student and community adult populations. This study investigated the relationships between nonattachment and three workplace-related variables, namely control at work, psychological safety, and supervisor support, on mental well-being of a representative sample of working adults in Hong Kong.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional investigation using the data provided by 1008 working adults who participated in a population-based telephone survey. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed to test how nonattachment may be related to mental well-being of working adults, with the relationship being mediated by three workplace-related variables.

Results

Results indicated that nonattachment was positively associated with flourishing. This association was mediated by perceived supervisor support and control at work. In addition, nonattachment was negatively related to depression and anxiety symptoms and the association was only mediated by perceived supervisor support. Psychological safety did not significantly mediate the effect of nonattachment on mental well-being.

Conclusions

This study provides suggestive evidence that staff’s perception towards supervisors and level of control at work can bridge the relationship between nonattachment and employee well-being. Potential cultural nuance that may have contributed to the nonsignificance of psychological safety was discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Nonattachment stems from Buddhist psychology and is defined as a quality with which a person does not cling to positive experience or avoid negative experience (Sahdra et al., 2015). Cultivating the attitude of nonattachment, also may be referred to as letting go, was suggested to be fundamental to mindfulness practice (Kabat-Zinn, 2009). When people are nonattached, they may recognize the transient nature of all phenomena, including their thoughts and feelings, and thus may realize the futility of clinging to any of them (Ostafin, 2015). Nonattachment allows one to be free of the desire for positive experiences or avoidance of negative experiences, enabling one to experience the present moment fully without dependency on external circumstances (Sahdra, 2010). According to the Buddhist psychological model (Grabovac et al., 2011), decreasing habitual attachment to feelings bridges between mindfulness practice and reduced mental proliferation that leads to suffering. A recent meta-analytic study (Ho et al., 2022) also supported the mediating role of nonattachment in the relationship between mindfulness with well-being and distress.

In the literature, nonattachment was found to be positively associated with mental well-being and negatively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress (Whitehead et al., 2019). Past studies have also demonstrated nonattachment to be associated with positive interpersonal processes, including greater levels of perspective taking, generosity, relational harmony, and compassion (Sahdra et al., 2010, 2015; Wang et al., 2016). Conversely, individuals’ tendency to avoid negative experiences was shown to predict poor interpersonal relationships (Zamir et al., 2018). In other words, nonattachment potentially has both intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits.

Existing evidence also alluded to the potential benefits of being nonattached in the workplace for working adults, who may be vulnerable to psychological distress, anxiety, and/or depression. In a recent meta-analysis (Salari et al., 2020), the average prevalence of anxiety was 31.9% (based on 17 studies covering 63,439 participants) and of depression was 33.7% (based on 14 studies covering 44,531 participants) in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sub-group analysis indicated that participants in Asia have higher levels of both anxiety (32.9% vs. 23.8%) and depression (35.3% vs. 32.4%) than their European counterparts. Hong Kong is one of Asia’s highest income cities that is notorious for its demanding work culture and long working hours (Cheung & Yip, 2015). According to a population-based telephone survey, an average working adult in Hong Kong spends 46.9 h per week at work (Tong et al., 2021). An epidemiological study conducted in Hong Kong showed that about 1 in 7 adults in the general population have common mental disorders, namely anxiety, depression, or a combination of the two (Lam et al., 2015). In another study, among the 1031 working adults surveyed, 25% of them reported feeling down, depressed, or hopeless in the previous month, and 90% of respondents reported needing more mental health support at work (Zhu et al., 2016). An added challenge in the recent year is the COVID-19 pandemic that triggers a global health and economic crisis, affecting people’s livelihood, health, and mental health. It is therefore important to understand what personal and workplace attributes may mitigate or exacerbate psychological distress among working adults during this critical period.

Nonattachment as Protective Disposition

Despite a considerable amount of interest in the effects of mindfulness on well-being, less attention is placed on understanding how individuals who are nonattached might differ in their mental well-being and interpersonal outcomes at work. Being nonattached, or nonclinging, seems to clash with the modern striving culture whereby individuals are compelled to strive for wealth and status in the hierarchy of organizations. However, with the quality of being nonattached, individuals may experience better well-being at work. Employees with higher levels of nonattachment were found to have better job satisfaction (Upadhyay & Vashishtha, 2014). Pande and Naiu (1992) found that employees who were more nonattached experienced significantly less distress and better mental health compared to those who were low in nonattachment despite the fact that they both experienced comparable occurrence of stressful life events.

Apparently, nonattachment as a dispositional quality influences one’s well-being at work more than the situation itself. It is plausible that workers who are more nonattached gained greater psychological autonomy and freedom in the workplace, which prompt them to perceive greater levels of control at work, feel more psychologically safe to express their views, and feel being more supported by their supervisors. Thus, although nonattachment may seem to run counter to a striving working culture nowadays, it may in fact facilitate working adults to gain workplace attributes that are conducive to their mental well-being.

Nonattachment on Control at Work

The notion of control was defined as having a sense of control over the external environment and the belief of one’s freedom and ability to make choices that affect an individual’s attitudes and actions (Ng et al., 2006). Control at work has its theoretical underpinnings associated with both the theory of locus of control (Wang et al., 2016) and the notion of decision latitude from the Job Control-Demand Model (Häusser et al., 2010). Job control is an important resource to buffer the effects of work-related demands (e.g., high workload, conflict of demand) on well-being (Ganster & Rosen, 2013) and job motivation and engagement (Fox et al., 1993; Kain & Jex, 2010). In organizational psychology, job control refers to a person’s skill discretion and autonomy in scheduling or organizing one’s tasks (Kain & Jex, 2010). Having high levels of perceived locus of control has been demonstrated to be conducive to one’s well-being (Colquitt et al., 2015; Ng et al., 2006). Conversely, a perceived lack of control is detrimental to health and mental health (e.g., Stansfeld & Candy, 2006), greater levels of stress, and lower self-worth (Langer, 1983).

Currently, no study to date has investigated the relationship between nonattachment and a sense of control at work. Tangential evidence however indicated that while nonattachment has an inverse relationship with external locus of control (Sahdra et al., 2010), theoretical linkage might exist between nonattachment and internal locus of control. Individuals with a higher sense of internal locus of control are less likely to be influenced by other people or external circumstances. People with higher levels of internal locus of control were found to have better interpersonal relationships at work, better coping skills, and experience less job stress, to name a few (see Wang et al., 2016 for a meta-analytic review). In general, they tend to perceive the workplace as more positive, compared to those with higher external locus of control. Likewise, people who have high levels of nonattachment may show more satisfaction at work due to their minimal need to maximize pleasant experiences or shun unpleasant experiences at work such that they may not be as concerned to promoting themselves or admitting mistakes. Moreover, individuals high in nonattachment may be predisposed to a greater sense of environmental mastery since they are not trapped by clinging feelings and thoughts (Whitehead et al., 2019). This quality is associated with people having an internal locus of control orientation (Shojaee & French, 2014). The empirical and theoretical evidence suggests that higher levels of nonattachment might be associated with higher levels of control at work.

Nonattachment on Psychological Safety

Psychological safety has been found to be critical in organizational well-being, personal learning, and development. Psychological safety is individuals’ perception of threat in their environment, in particular, the consequences of taking certain work-related risks in the workplace. People with a high sense of psychological safety are thought to be more willing to express their views and can accept failures without fear of punishment or retaliation (Edmondson, 1999; Kahn, 1990). Edmondson (2004) conceptualized psychological safety as an interpersonal construct, a person’s willingness to take risks in the team, without fear of guilt or adverse consequences. Psychological safety has shown to be associated with a myriad of positive work outcomes, including creativity (Gu et al., 2013), work engagement (May et al., 2004), enhanced interpersonal communication (Edmondson & Lei, 2014), and willingness to share knowledge and engage in voice behaviors (Bienefeld & Grote, 2014). Furthermore, in the systematic review by Newman et al. (2017), psychological safety is found to be a mediator between positive job resources and work stress.

Although the relationship between psychological safety and nonattachment has not been empirically investigated, some conceptual linkage could be found. For example, when people stop being self-fixated at work, such as clinging to a need to be praised or validated by others, a sense of spiritual freedom ensues (Agarwal, 1982; Sumedho, 1989). This sense of freedom might enable people to act on their goals or values in a more effective manner with less self-interests in mind, which is congruent with the attitudes of people who have a high sense of psychological safety. In other words, when people are not attached to expectations or positive outcomes, a sense of psychological safety may come along with greater freedom to respond in difficult situations.

Nonattachment on Perceived Supervisor Support

Perceived supervisor support refers to the perceptions that their supervisors or line managers are rendering supportive behaviors to them as employees. Perceived supervisor support, among all interpersonal variables in the workplace, was cited as one of the most important influences on employee well-being and performance in the workplace, regardless of industries and occupations (LaMontagne et al., 2014). Support from supervisor also renders a stronger effect in buffering job strain than support from co-workers from the same workplace (Karasek et al., 1982). In fact, among all kinds of social support (family and work), a perceived lack of support from supervisors at work was found to be the strongest predictor or risk factor for negative mental health and health outcomes, including self-rated health, musculoskeletal disorders, stressful feelings, burnout symptoms, and turnover intention (Hämmig, 2017). Conversely, higher levels of perceived supervisor support are associated with a reduction of job stress (Kang & Kang, 2016).

To date, no study has been conducted to directly examine the relationship between nonattachment and perceived supervisor support. However, a handful of studies have shown the positive relationship between nonattachment and interpersonal relationships. Whitehead et al. (2018) found people who were highly nonattached had their relationships benefitted by letting go of expectations of others. Attached individuals often hold inflexible expectations about how people should behave. When these expectations were not met, people with low levels of nonattachment might display a tendency to feel frustrated in the relationships or judge them as unworthy. In the context of workplace, expectations towards work and performance may be inevitable. Nonattachment enables employees to uncling from expectations and be able to consider the situations as they are. As such, employees who are dispositionally more nonattached may be less likely to hold grudges, be more able to have a less biased view of their supervisors that is shaped by their past experiences, and have greater latitude to perceive support from their supervisors.

Past studies have found dispositional mindfulness to correlate positively with perceived social support (Klainin-Yobas et al., 2016; Mettler et al., 2019). Given mindfulness has been found to be positively related to nonattachment (Sahdra et al., 2010) and nonattachment was found to mediate the relationship between mindfulness with well-being (Ho et al., 2022) and enhanced interpersonal behaviors (e.g., Glomb et al., 2011; Whitehead et al., 2019), these nonattached workers may also have more interpersonal skills and being more mindful at work, and may, as a result, elicit more support from their supervisors.

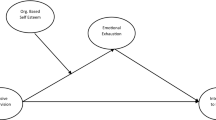

Consistent with these theoretical and empirical perspectives, the present study aimed to examine the contribution of nonattachment to the mental well-being of working adults and to investigate whether these three important work variables, control at work, psychological safety, and perceived supervisor support, can mediate the relationship between nonattachment and well-being. We hypothesized that (1) higher levels of nonattachment are associated with better mental well-being outcomes and (2) the association between nonattachment and mental well-being would be mediated by control at work, psychological safety, and perceived supervisor support. Through establishing the relationships of these variables, further theories can be developed to examine how nonattachment can be understood and fostered in the workplace to promote mental well-being.

Methods

Participants

Data were collected from 1008 full-time working adults who took part in a cross-sectional, population-based phone survey in 2017. Among the respondents, 90.7% of them fell between ages 18 and 59 with most of them (31.3%) aged between 50 and 59. An even distribution of gender was achieved, with 49.3% of respondents being female. They came from 21 different industries representing a diverse sample of working adults in Hong Kong, including construction (11.9%), education (9.6%), hospitality (7.8%), civil services (7.7%), medical health and welfare (7.4%), and banking and finance (7.2%) as well as wholesale and retail (7.1%). Over half of the respondents (54.9%) worked in local companies, 15.7% worked in international companies, and 14.7% worked in the government. In terms of position, 36.8% of them self-reported as professionals, managers, or executives, and 31.7% were nonskill workers. Respondents’ monthly income spread widely from less than $5000 to over $100,000 Hong Kong dollars (HKD) and about half (53.4%) of the respondents earned HKD$15,000–HKD$39,999 per month. An average weekly working time of 48.03 h (SD = 10.88) was reported. In terms of mental well-being, 21.4% of the respondents were identified as having probable anxiety using the suggested cut-off score of 3 on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2; Spitzer et al., 2006), 14% as having probable depression based on the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2; Kroenke et al., 2003), and 10.4% meeting both cut-offs for probable anxiety and depression.

Procedures

The Public Opinion Program (POP) at the University of Hong Kong was commissioned to conduct the population-based telephone survey. Landline and mobile telephone numbers were randomly generated. For the landline telephone number samples, when contact was successfully established with a target household, a person who is 18 years old or above, working full-time, was selected from all those qualified who were also present using the “next birthday” rule. Each target telephone number was called a maximum of 5 times, including different call attempts made during daytime and in the evenings before it was dropped as “non-contact.” If the target respondent was not immediately available to answer the survey at the time when the initial call was made, interviewers would make attempts to gain their cooperation by re-calling at different time slots, or by making an appointment with the respondents and re-called at a specific time slot. Explicit refusals from the target respondents or other household members were recorded as unsuccessful cases and no more re-calls would be made. After respondents are identified and successfully contacted, they were briefed about the study aims and verbal consent sought. No second-level sampling was in place for the mobile samples.

Measures

Nonattachment

To capture one’s flexibility and balanced approach towards life experiences, the 8-item Nonattachment Scale-Short Form (NAS-SF; Chio et al., 2018; Sahdra et al., 2010) was used. Respondents are asked to rate their agreement to the items on a 6-point scale, from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. A sample item is: “I can let go of regrets and feelings of dissatisfaction about the past.” This abridged version was developed using item response theory for Chinese in Hong Kong (Chio et al., 2018). In the present sample, the NAS-SF had an internal consistency of Cronbach’s α = 0.84 and McDonald’s ω = 0.85.

Control at Work

The 3-item Control at Work (CAW) subscale from the Work-related quality of life (WRQoL) scale (Van Laar et al., 2007) was used to capture the extent in which participants felt they could involve in decision-making pertinent to their work, such as “I am involved in decisions that affect me in my own area of work.” The scale ranged from 1 to 5 (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). The internal consistency of the 3 items was Cronbach’s α = 0.80 and McDonald’s ω = 0.80 in the present study.

Psychological Safety

Psychological safety was measured using the 7-item scale from Edmondson’s (1999) Team Psychological Safety scale. Sample items included “Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues” and “If you make a mistake on this team, it is often held against you.” The scale ranged from 1 to 7 (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = neutral; 7 = strongly agree). The internal consistency of these 7 items was Cronbach’s α = 0.63 and McDonald’s ω = 0.64. Based on the factor loadings of a forced single-factor principal component analysis (PCA), one item (“No one on this team would deliberately act in a way that undermines my efforts.”) obtained a low communality score of 0.03. This item was removed following Child’s (2006) suggestion that an item with a communality score less than 0.2 should be removed. Upon removal, the scale internal consistency improved to Cronbach’s α = 0.698 and McDonald’s ω = 0.70.

Perceived Supervisor Support

To assess respondents’ perceptions towards their supervisor’s support on their contributions and well-being, we selected four highest loading items from the Scale of Perceived Organization Support (Eisenberger et al., 1986) and replaced the term “organization” with “supervisor.” Similar practice was found in other studies (e.g., Eisenberger et al., 2002; Rhoades et al., 2001). Sample items include “My supervisor cares about my opinion” and “My supervisor strongly considers my goals and values.” Participants rated their responses on a 7-point scale, with 1 = strongly disagree; 4 = neutral; and 7 = strongly agree. The four items had an internal consistency of Cronbach’s α = 0.82 and McDonald’s ω = 0.83 in the present study.

Mental Well-being

Depression, anxiety, and flourishing were measured respectively using the PHQ-2, GAD-2, and the Flourishing Scale (FS; Diener et al., 2010). PHQ-2 and GAD-2 are brief screening tools for depression and anxiety. Each scale consists of 2 items, with a scale point that ranges from 0 to 3 (0 = not at all; 3 = nearly every day). Using a cut-off of 3, the GAD-2 has a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 83% for diagnosing generalized anxiety disorder (Plummer et al., 2016), and PHQ-2 has a sensitivity of 82.9% and specificity of 90% for detecting major depressive disorder (Gilbody et al., 2007). The two measures were commonly combined to represent an individual’s symptoms of depressive and anxiety (PHQ-4; Kroenke et al., 2009). The PHQ-4 had an internal consistency of Cronbach’s α = 0.82 and McDonald’s ω = 0.83 in the present study.

The Flourishing Scale has been employed widely to measure mental well-being and have attained strong psychometric properties (Diener et al., 2010). It is a widely recognized tool to capture a respondent’s self-perceived satisfaction in different aspects of life, including interpersonal relationship and sense of purpose; respondents are asked to rate on a set of statements on a scale of 1 to 7 (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = neutral; 7 = strongly agree). Flourishing is conceptually different from happiness or hedonic well-being as flourishing is thought to encompass a broader state of well-being of a person (Van der Weele, 2017). Its internal consistency was Cronbach’s α = 0.84 and McDonald’s ω = 0.85.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS package version 26 to examine respondents’ demographic characteristics. Zero-order correlations were obtained in SPSS to explore the intercorrelations of variables to be included in the structural equation modeling (SEM). Principal component factoring with varimax rotation was performed to obtain factor loadings for the items of each hypothetical latent construct to be used in subsequent item-parceling procedure.

The Mplus 7.0 software package (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) was used to perform SEM. Maximum likelihood estimation was used to handle missing data and to produce covariance matrices. Three item parcels were computed for each latent construct based on the factor loadings with accordance to the factorial algorithm (Rogers & Schmitt, 2004). For constructs that were assessed by less than 5 items, all items were used directly to indicate the latent construct. A combination of goodness-of-fit criteria was considered, including the absolute goodness-of-fit statistic chi-square (χ2), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Values of both RMSEA and SRMR over 0.08 and CFI and TLI values over 0.90 indicate acceptable model fit (Brown & Cudeck, 1993).

A two-step approach was adopted in this study. The first step was a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the factor structure of the measurement model. To produce reliable results, items’ factor loadings should be over 0.4. In addition, construct reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were calculated using these factor loadings to determine convergent and discriminant validity. AVE of each construct should be larger than its correlations with the other constructs and over 0.5. CR should be over 0.7 to demonstrate validity (Hair et al., 2010).

The second step was a full SEM testing the hypothesized model as illustrated in Fig. 1. Specifically, the four items of PHQ-2 and GAD-2 were modeled into a latent factor representing depressive and anxiety symptoms. It was treated as the outcome in the model together with flourishing. Nonattachment was treated as the predictor and the three work determinants, i.e., control at work, psychological safety, perceived supervisor support, were treated as mediators. Nonattachment, depressive and anxiety symptoms, and flourishing were adjusted for age and gender (dummy coded). Mediation effects were tested with the bootstrapping procedures recommended by Shrout and Bolger (2002). Bias corrected bootstrap confidence intervals were estimated using 1000 bootstrapped samples from the original data following Cheung and Lau (2008).

Results

The means, standard deviations, and correlations of all observed variables are presented in Table 1. All variables were significantly correlated (p < 0.05), providing a solid basis for model testing. Factor loadings, validity, and reliability analysis for the study variables are presented in Table 2. Results of the confirmatory factor analysis showed that the measurement model had a satisfactory model fit (χ2(155) = 614.78, CFI = 0.946, TLI = 0.934, RMSEA = 0.054 (CI: 0.050–0.059), SRMR = 0.047), indicating that the proposed factor structure was supported statistically and therefore all variables were retained in the full SEM.

Figure 2 shows the final model and Table 3 presents the statistics of direct and indirect effects. Results indicated that most of the fit indices were satisfactory (CFI = 0.935, TLI = 0.922, RMSEA = 0.048 (CI: 0.044–0.052), SRMR = 0.044). The paths from psychological safety to both well-being indicators, i.e., flourishing and depressive and anxiety symptoms, were nonsignificant; the path from control at work to depressive and anxiety symptoms was also not significant. All other paths were statistically significant and in line with the hypothesized direction. The proposed model explained 50% of the variance in flourishing, and 20.7% of the variance in depressive and anxiety symptoms.

The composite indirect effect of nonattachment on flourishing through control at work and perceived supervisor support was significant (β = 0.17, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001), suggesting that respondents with higher levels of nonattachment were more likely to flourish as mediated by an increase in control and supervisor’s support at work. In addition, the indirect effect of nonattachment on depressive and anxiety symptoms through perceived supervisor support was also significant (β = − 0.04, SE = 0.02, p < 0.05), indicating that respondents with higher levels of nonattachment reported less depressive and anxiety symptoms as mediated by increased supervisor’s support.

Discussion

This study investigated the associations of nonattachment with workplace attributes, namely control at work, psychological safety, and perceived supervisor support, and its relationships with mental well-being and psychological distress of working adults. Our results indicated that nonattachment is positively linked with flourishing, and negatively linked with depressive and anxiety symptoms. Moreover, out of the three variables hypothesized to mediate the relationship between nonattachment with depressive and anxiety symptoms, only perceived supervisor support was demonstrated to be a significant mediator. For the relationship between nonattachment and flourishing, both control at work and perceived supervisor support were found to be significant mediators. Psychological safety was not a significant mediator after accounting for the other two work-related factors.

This study provides new insights on the theoretical linkage between dispositional nonattachment, perceived support from supervisors at work, and control at work. It adds new perspectives to existing literature that predominantly focused on the ways in which workplace attributes impact working adults’ well-being. The present study provided preliminary evidence that being nonattached may predispose people to experience control at work and perceive stronger support from their supervisors.

Nonattachment has not been studied empirically in the work setting. Establishing the linkage between dispositional nonattachment and perceived support from supervisors supports existing research on the interpersonal benefits of being nonattached (Joss et al., 2020). It also goes beyond existing literature by demonstrating the benefits of being nonattached have on workplace relationships, which are said to be more “functional” for one’s career, from a social exchange lens (Colbert et al., 2016). Apart from bringing benefits to interpersonal relationships, our results also suggested that individuals who are less reactive to life’s experiences are more likely to feel a greater sense of control at work, paradoxical as it may seem. This is in accord with Wu et al.’s (2019) study that found people whose nonattachment were cultivated through the practice of an awareness training program (ATP) also experienced an increased sense of coherence in life. People with a higher sense of coherence are more likely to find life comprehensible and manageable, rather than finding life as chaotic and meaningless (Antonovsky, 1993). Both nonattachment and sense of coherence are salient in cognitive appraisal and coping, and previous studies have demonstrated the importance of sense of coherence as an important predictor for work-related health and well-being (Albertsen et al., 2001; Nielsen et al., 2008).

Contrary to our prediction, psychological safety was not a significant mediator in both models. This could be due to the relatively poor internal consistency between the psychological safety items observed in our sample. Another possible explanation for the nonsignificant finding could be a difference in cultural nuances. Psychological safety is predominantly a Western, individualistic notion, which alludes to a person’s willingness to take risks in a work setting without worrying about negative consequences. However, although Hong Kong is an international metropolitan city, high power distance and collectivism still prevail in many work settings (Leung, 2012), and group performance, rather than individual performance relative to other in-group members, is valued more highly in collectivistic cultures (Halevy & Sagiv, 2008). Compatible with this theoretical lens, we conjectured that our respondents may not find psychological safety to be an important determinant for workplace well-being.

To further interpret the current findings, relevant theories such as the social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) could be considered. According to the social identity theory and other identity models built on its premises, self-identity is a strong force that shapes the attitudes and behaviors of employees in a workplace and life in general (Ellemers et al., 2003). Indeed, most organizational studies operate on the theoretical foreground that assumes individuals to hold salient narrative identities at work (e.g., I am a medical doctor). This narrative of the self is what shapes individual’s experience and reality at work and life in general (Ashforth et al., 2008). However, this sense of “self” juxtaposes with the notion of nonattachment. Nonattachment entails nonclinging to work arrangements and events at work and work outcomes, as well as the sense of self of being a certain kind of worker or being. Therefore, future research can investigate how one’s clinging (or nonclinging) to the sense of “self” may interact with one’s attitudes and adjustment at work, especially in a culturally diverse setting. Nonattachment to the self was found to be positively related to emotional stability, self-transcendence, environmental mastery, autonomy and negatively related to stress, depression, and anxiety (Whitehead et al., 2018). It may be possible that when people can nonattach from their sense of self, they can more freely interact with different ranks of colleagues and maneuver across work settings, without being entangled in fixed perceptions of who they should be, what they should do, and how they should communicate with others in the workplace.

Limitations and Future Research

The findings of this study should be interpreted with its limitations in mind. First, even though the sample was representative, the cross-sectional design of this study precludes any establishment of causality. The findings obtained from this study could serve as a theoretical foundation for future studies to test the hypothesized model over time, preferably with an experimental or interventional component. Secondly, the relatively low internal consistency obtained for the measure of psychological safety may contribute to its nonsignificant relationships with mental well-being outcomes.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study provides solid groundwork for future theory-driven predictions to be made between the relationships of nonattachment and both intra- and interpersonal well-being in the workplace. While our study did not find significant linkage between psychological safety and mental well-being, one possible direction could be to explore the underlying reason. As discussed earlier, we speculated that the difference in cultural nuances may have an influence. Future studies may consider conducting a cross-culture investigation to confirm this hypothesis.

Nevertheless, this study provided suggestive evidence that promoting nonattachment at the workplace may have positive impacts on employee well-being. Limited by the cross-sectional nature, causality could not be drawn in this study. Future studies may consider conducting a randomized control trial to test the efficacy of a workplace-specific nonattachment training on improving employee well-being.

Data Availability

All data are available at the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/2v7mn).

References

Agarwal, M. M. (1982). Philosophy of non-attachment The way to spiritual freedom in Indian thought. Motilal Banarsidass Publications.

Albertsen, K., Nielsen, M. L., & Borg, V. (2001). The Danish psychosocial work environment and symptoms of stress: The main, mediating and moderating role of sense of coherence. Work & Stress, 15(3), 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370110066562

Antonovsky, A. (1993). The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Social Science & Medicine, 36(6), 725–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-Z

Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34, 325–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0149206308316059

Bienefeld, N., & Grote, G. (2014). Speaking up in ad hoc multiteam systems: Individual-level effects of psychological safety, status, and leadership within and across teams. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(6), 930–945. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2013.808398

Bond, F. W., & Flaxman, P. E. (2006). The ability of psychological flexibility and job control to predict learning, job performance, and mental health. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 26(1–2), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1300/J075v26n01_05

Bond, F. W., & Hayes, S. C. (2002). ACT at work. In F. W. Bond & W. Dryden (Eds.), Handbook of brief cognitive behaviour therapy (pp. 117–139). John Wiley & Sons.

Bond, F. W., Flaxman, P. E., & Bunce, D. (2008). The influence of psychological flexibility on work redesign: Mediated moderation of a work reorganization intervention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 645–654. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.645

Brown, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 154, 136–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0049124192021002005

Cheung, G. W., & Lau, R. S. (2008). Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 296–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1094428107300343

Cheung, T., & Yip, P. S. (2015). Depression, anxiety and symptoms of stress among Hong Kong nurses: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(9), 11072–11100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120911072

Child, D. (2006). The essentials of factor analysis (3rd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic.

Chio, F. H. N., Lai, M. H. C., & Mak, W. W. S. (2018). Development of the nonattachment scale-short form (NAS-SF) using item response theory. Mindfulness, 9(4), 1299–1308. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12671-017-0874-Z

Colbert, A. E., Bono, J. E., & Purvanova, R. K. (2016). Flourishing via workplace relationships: Moving beyond instrumental support. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4), 1199–1223. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0506

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., & Wesson, M. J. (2015). Organizational behavior: Improving performance and commitment in the workplace (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D. W., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2F2666999

Edmondson, A. C. (2004). Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: A group-level lens. In R. M. Kramer & K. S. Cook (Eds.), Trust and distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches (pp. 239–272). Russell Sage Foundation.

Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety The history renaissance and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

Eisenberger, R., Stinglhamber, F., Vandenberghe, C., Sucharski, I. L., & Rhoades, L. (2002). Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 565. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.565

Ellemers, N., Haslam, S. A., Platow, M. J., & van Knippenberg, D. (2003). Social identity at work: Developments, debates, directions. In S. A. Haslam, D. van Knippenberg, M. J. Platow, & N. Ellemers (Eds.), Social identity at work: Developing theory for organizational practice (pp. 3–26). Psychology Press.

Fox, M. L., Dwyer, D. J., & Ganster, D. C. (1993). Effects of stressful job demands and control on physiological and attitudinal outcomes in a hospital setting. Academy of Management Journal, 36(2), 289–318. https://doi.org/10.5465/256524

Ganster, D. C., & Rosen, C. C. (2013). Work stress and employee health: A multidisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 39(5), 1085–1122. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0149206313475815

Gilbody, S., Richards, D., Brealey, S., & Hewitt, C. (2007). Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): A diagnostic meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(11), 1596–1602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0333-y

Glomb, T. M., Duffy, M. K., Bono, J. E., & Yang, T. (2011). Mindfulness at work. In A. Joshi, H. Liao, & J. J. Martocchio (Eds.), Research in personnel and human resources management (pp. 115–157). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Grabovac, A. D., Lau, M. A., & Willett, B. R. (2011). Mechanisms of mindfulness: A Buddhist psychological model. Mindfulness, 2(3), 154–166.

Gu, Q., Wang, G. G., & Wang, L. (2013). Social capital and innovation in R&D teams: The mediating roles of psychological safety and learning from mistakes. R&D Management, 43(2), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12002

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Prentice Hall.

Halevy, N., & Sagiv, L. (2008). Teams within and across cultures. In P. B. Smith, M. F. Peterson, & D. C. Thomas (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural management research (pp. 253–268). Sage.

Hämmig, O. (2017). Health and well-being at work: The key role of supervisor support. SSM-Population Health, 3, 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.04.002

Häusser, J. A., Mojzisch, A., Niesel, M., & Schulz-Hardt, S. (2010). Ten years on: A review of recent research on the Job Demand-Control (-Support) model and psychological well-being. Work & Stress, 24(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678371003683747

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behavior Research and Therapy, 44, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

Ho, C. Y. Y., Yu, B. C. L., & Mak, W. W. S. (2022). Nonattachment mediates the associations between mindfulness, well-being, and psychological distress: A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach. Clinical Psychology Review, 95, 102175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102175

Joss, D., Lazar, S. W., & Teicher, M. H. (2020). Nonattachment predicts empathy, rejection sensitivity, and symptom reduction after a mindfulness-based intervention among young adults with a history of childhood maltreatment. Mindfulness, 11(4), 975–990. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01322-9

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2009). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Delta.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 692–724. https://doi.org/10.5465/256287

Kain, J. and Jex, S. (2010). Karasek's (1979) Job demands-control model: A summary of current issues and recommendations for future research. In P.L. Perrewé & D.C. Ganster (Eds.), New developments in theoretical and conceptual approaches to job stress (pp. 237–268). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-3555(2010)0000008009

Kang, S. W., & Kang, S. D. (2016). High-commitment human resource management and job stress: Supervisor support as a moderator. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 44(10), 1719–1731. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.10.1719

Karasek, R. A., Triantis, K. P., & Chaudhry, S. S. (1982). Coworker and supervisor support as moderators of associations between task characteristics and mental strain. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 3(2), 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030030205

Klainin-Yobas, P., Ramirez, D., Fernandez, Z., Sarmiento, J., Thanoi, W., Ignacio, J., & Lau, Y. (2016). Examining the predicting effect of mindfulness on psychological well-being among undergraduate students: A structural equation modelling approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 91, 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.034

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000093487.78664.3c

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ–4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), 613–621.

Lam, L. C. W., Wong, C. S. M., Wang, M. J., Chan, W. C., Chen, E. Y. H., Ng, R. M. K., Hung, C. F., Cheung, E. F. C., Sham, P. C., Chiu, H. F. K., & Lam, M. (2015). Prevalence, psychosocial correlates and service utilization of depressive and anxiety disorders in Hong Kong: The Hong Kong Mental Morbidity Survey (HKMMS). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(9), 1379–1388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1014-5

LaMontagne, A. D., Keegel, T., Shann, C., & D’Souza, R. (2014). An integrated approach to workplace mental health: An Australian feasibility study. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 16(4), 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2014.931070

Langer, E. J. (1983). The psychology of control. Sage.

Leung, K. (2012). Different carrots for different rabbits: Effects of individualism–collectivism and power distance on work motivation. In M. Erez, U. Kleinbeck, & H. Thierry (Eds.), Work motivation in the context of a globalizing economy (pp. 328–338). Psychology Press.

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904322915892

Mettler, J., Carsley, D., Joly, M., & Heath, N. L. (2019). Dispositional mindfulness and adjustment to university. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 21(1), 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1521025116688905

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2009). Mplus. Statistical analysis with latent variables. User’s guide (7th ed.). Yumpu.

Newman, A., Donohue, R., & Eva, N. (2017). Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001

Ng, T. W., Sorensen, K. L., & Eby, L. T. (2006). Locus of control at work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(8), 1057–1087. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.416

Nielsen, M. B., Matthiesen, S. B., & Einarsen, S. (2008). Sense of coherence as a protective mechanism among targets of workplace bullying. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(2), 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.13.2.128

Ostafin, B. D. (2015). Taming the wild elephant: Mindfulness and its role in overcoming automatic mental processes. In B. D. Ostafin, M. D. Robinson, & B. P. Meier (Eds.), Handbook of mindfulness and self-regulation (pp. 47–63). Springer Science.

Pande, N., & Naidu, R. K. (1992). Anāsakti and health: A study of non-attachment. Psychology and Developing Societies, 4(1), 89–104.

Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005

Rhoades, L., Eisenberger, R., & Armeli, S. (2001). Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 825–836. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.825

Rogers, W. M., & Schmitt, N. (2004). Parameter recovery and model fit using multidimensional composites: A comparison of four empirical parcelling algorithms. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 379–412. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327906MBR3903_1

Sahdra, B. K., Shaver, P. R., & Brown, K. W. (2010). A scale to measure nonattachment: A Buddhist complement to Western research on attachment and adaptive functioning. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(2), 116–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890903425960

Sahdra, B. K., Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P. D., Marshall, S., & Heaven, P. (2015). Empathy and nonattachment independently predict peer nominations of prosocial behavior of adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 263. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00263

Salari, N., Hosseinian-Far, A., Jalali, R., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., Rasoulpoor, S., & Khaledi-Paveh, B. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

Shojaee, M., & French, C. (2014). The relationship between mental health components and locus of control in youth. Psychology, 5, 966–978. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2014.58107

Shrout, P. E. Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Stansfeld, S., & Candy, B. (2006). Psychosocial work environment and mental health—A meta-analytic review. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 32(6), 443–462. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1050

Sumedho, A. (1989). Now is the knowing. Amaravati Publications.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

Tong, A. C. Y., Tsoi, E. W. S., & Mak, W. W. S. (2021). Socioeconomic status, mental health, and workplace determinants among working adults in Hong Kong: A latent class analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 7894. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157894

Upadhyay, P. P., & Vashishtha, A. C. (2014). Effect of anasakti and level of post job satisfaction on employees. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 2(1), 100–107.

Van der Weele, T. J. (2017). On the promotion of human flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(31), 8148–8156. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702996114

Van Laar, D., Edwards, J. A., & Easton, S. (2007). The Work-Related Quality of Life scale for healthcare workers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 60(3), 325–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04409.x

Wang, S. Y., Wong, Y. J., & Yeh, K. H. (2016). Relationship harmony, dialectical coping, and nonattachment: Chinese indigenous well-being and mental health. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(1), 78–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0011000015616463

Whitehead, R., Bates, G., Elphinstone, B., Yang, Y., & Murray, G. (2018). Letting go of self: The creation of the nonattachment to self scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2544. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02544

Whitehead, R., Bates, G., Elphinstone, B., Yang, Y., & Murray, G. (2019). Nonattachment mediates the relationship between mindfulness and psychological well-being, subjective well-being, and depression, anxiety and stress. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(7), 2141–2158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0041-9

Wu, B. W. Y., Gao, J., Leung, H. K., & Sik, H. H. (2019). A randomized controlled trial of awareness training program (ATP), a group-based Mahayana Buddhist intervention. Mindfulness, 10(7), 1280–1293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1082-1

Zamir, O., Gewirtz, A. H., Labella, M., DeGarmo, D. S., & Snyder, J. (2018). Experiential avoidance, dyadic interaction and relationship quality in the lives of veterans and their partners. Journal of Family Issues, 39(5), https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0011000015616463

Zhu, S., Tse, S., Tang, J., & Wong, P. (2016). Knowledge, attitudes and behaviors associated with mental illness among the working population in Hong Kong: A cross-sectional telephone survey. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 9(3), 313–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/17542863.2016.1198409

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the research participants involved in this study.

Funding

This study was funded by The Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust for the project entitled “A Stepped-Care Online Self-help and Support Service Project on Mental Health” (2017/0070).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EWST contributed to the study conception, executed the study, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. ACYT analyzed the data, wrote the results, collaborated in the writing of the manuscript, addressed reviewers’ comments, and revised the manuscript. WWSM secured grant funding, designed the study, interpreted the results, and collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Research ethics approval was obtained from the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee, The Chinese University of Hong Kong (Ref. No. 7105544).

Inform Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsoi, E.W.S., Tong, A.C.Y. & Mak, W.W.S. Nonattachment at Work on Well-being Among Working Adults in Hong Kong. Mindfulness 13, 2461–2472 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01971-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01971-y