Abstract

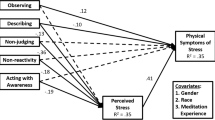

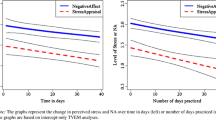

Research has indicated that the “observing” facet of mindfulness fits a hierarchical factor structure in which specific facets relate to a general mindfulness factor, and correlates with well-being, only among meditators. We extended this research by testing whether observing functions differently among meditators in terms of buffering the effects of stress on distress. Participants (N = 190 including 78 meditators) completed measures of life events, mindfulness, and distress symptoms. As hypothesized, there was a significant interaction of observing × stress × meditation, such that the effect of stress on distress was smallest among meditators scoring high on observing. Additional research is needed to test alternate interpretations (e.g., self-selection of meditation as an enjoyable practice by those who can observe in an adaptive manner), but the results suggest that meditation helps people learn to observe internal and external experience in an unbiased manner lending itself to constructive coping.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Agee, J. D., Danoff-Burg, S., & Grant, C. A. (2009). Comparing brief stress management courses in a community sample: mindfulness skills and progressive muscle relaxation. Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing, 5, 104–109. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2008.12.004.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. London: Sage Publications, Inc.

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 125–143. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bpg015.

Baer, R., Smith, G., & Allen, K. (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: the Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Assessment, 11, 191–206. doi:10.1177/107319110426802.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13, 27–45. doi:10.1177/1073191105283504.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., & Walsh, E. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15, 329–342. doi:10.1177/1073191107313003.

Baer, R. A., Samuel, D. B., & Lykins, E. L. B. (2011). Differential item functioning on the five facet mindfulness questionnaire is minimal in demographically matched meditators and nonmeditators. Assessment, 18, 3–10.

Bohlmeijer, E., ten Klooster, P. M., Fledderus, M., Veehof, M., & Baer, R. (2011). Psychometric properties of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in depressed adults and development of a short form. Assessment, 18, 308–320.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.82.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. doi:10.2307/2136404.

Curtiss, J., & Klemanski, D. H. (2014). Factor analysis of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in a heterogeneous clinical sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 36(4), 683–694.

Derogatis, L. R., & Melisaratos, N. (1983). The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13, 595–605. doi:10.1017/S0033291700048017.

Herbert, J. D., & Forman, E. M. (Eds.). (2011). Acceptance and mindfulness in cognitive behavior therapy. Hoboken: Wiley.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Dell Publishing.

Keng, S.-L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychological Review, 31, 1041–1056. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1121–1134. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121.

Pengilly, J., & Dowd, E. (2000). Hardiness and social support as moderators of stress. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56, 813–820. doi:10.1002/%28SICI%291097-4679%28200006%2956:6%3C813::AID-JCLP10%3E3.0.CO;2-Q.

Sarason, I. G., Johnson, J. H., & Siegel, J. M. (1978). Assessing the impact of life changes: development of the life experiences survey. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46, 932–946. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.46.5.932.

Tanner, M. A., Travis, F., Gaylord-King, C., Haaga, D. A. F., Grosswald, S., & Schneider, R. H. (2009). The effects of the transcendental meditation program on mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65, 574–589. doi:10.1002/jclp.20544.

Van Dam, N. T., Earleywine, M., & Danoff-Burg, S. (2009). Differential item function across meditators and non-meditators on the five facet mindfulness questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 516–521.

Williams, M. J., Dalgleish, T., Karl, A., & Kuyken, W. (2014). Examining the factor structures of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire and the self-compassion scale. Psychological Assessment, 26, 407–418. doi:10.1037/a0023366.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neale-Lorello, D., Haaga, D.A.F. The “Observing” Facet of Mindfulness Moderates Stress/Symptom Relations Only Among Meditators. Mindfulness 6, 1286–1291 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0396-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0396-5