Abstract

Alpine grasslands of the Neotropical Andes have high soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks and provide crucial ecosystem services. However, stability of the SOC in these grasslands is not well-studied. Having insights into SOC stability contributes to a better understanding of ecosystem vulnerability and maintaining of ecosystem services. The objectives were to get a first insight into organic matter (OM) stabilization in soils from different bedrocks of Andean alpine grasslands near Cajamarca, Peru (7° 11″ S, 78° 35″ W) and how this controls SOC stocks. Samples were collected from soils formed on limestone and acid igneous rocks. Stabilization mechanisms of OM were investigated using selective extraction methods separating active Fe, Al and Ca fractions and determined SOC stocks. In both soil types, the results showed important contributions of complexation with and/or adsorption on Fe and Al (oxides) to OM stabilization. Exclusively in the limestone soils, Ca induced OM stabilization by promoting the formation of Ca2+ bridges between OM and mineral surfaces. Furthermore, no evidence showed that OM stabilization was controlled by crystalline Fe oxides, clay contents, allophones, Al toxicity or aggregate stability. Limestone soils had significantly higher SOC stocks (405 ± 42 Mg ha−1) compared to the acid igneous rock soils (226 ± 6 Mg ha−1), which is likely explained by OM stabilization related to Ca2+ bridges in addition to the stabilization related to Fe and Al (oxides) in the limestone soils. Our results suggest a shift from OM stabilization dominated by Fe and Al (oxides) to that with the presence of Ca-related cation bridges, with increasing pH values driven by lithology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The soil acts as the largest terrestrial carbon (C) pool and plays an important role in global C dynamics (Lal 2004; Luo et al. 2016). Alpine grassland soils of the Neotropical Andes are characterized by their high soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks and play an important role as the water source for the coastal regions with an arid climate (Tonneijck et al. 2010; Buytaert et al. 2011; Rolando et al. 2017b). However, these grasslands suffer high risks of degradation due to ongoing and future climate change (Gang et al. 2014). To assess the vulnerability of the SOC stocks and the relevant ecosystem services, it is crucial to understand the mechanisms responsible for the stability of the SOC (Buytaert et al. 2011; Rolando et al. 2017b). However, SOC stability is not fully understood, as it is controlled by various environmental and soil formation factors at different scales (Wiesmeier et al. 2019). Most studies on SOC stocks and stabilization in ash soils of the Andean regions focused on the Páramo ecosystem in Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela and northern Peru (Buytaert et al. 2006; Tonneijck et al. 2010; Hribljan et al. 2016). However, soils formed on substrates other than volcanic ash, such as soils that occur in the central and southern Peruvian highland, also contain large SOC stocks. These soils have received less attention, especially with respect to the persistence and stability of the SOC (Zimmermann et al. 2009; Muñoz García and Faz Cano 2012; Rolando et al. 2017a).

The dynamics and turnover of SOC are largely controlled by the stabilization of soil organic matter (OM) (Sollins et al. 1996; Six et al. 2002). Recently, we have seen a shift from traditional views of soil OM stabilization based on the ‘humification’ model and molecular recalcitrance to a new paradigm based on the protection of soil OM by the soil matrix against decomposers (Schmidt et al. 2011; Dungait et al. 2012; Lehmann and Kleber 2015). In this paradigm, soil physicochemical properties regulate the maximum capacity to stabilize OM (Six et al. 2002). In general, soil OM is considered to be stabilized by: (1) recalcitrance of OM compounds due to their chemical properties, (2) spatial inaccessibility against decomposers because of the protection of soil aggregates, and (3) reduced availability to decomposers as a result of interaction with soil mineral surfaces and metal ions (Lützow et al. 2006). The interaction between OM and the mineral surfaces is considered as a key stabilization mechanism, and controls long-term retention of the OM (Schrumpf et al. 2013; Kleber et al. 2015). In acidic soils, the OM is generally stabilized by ligand exchange with non-crystalline Fe and Al oxides, as well as complexation with Fe and Al cations. In neutral and alkaline soils, the OM is thought to be stabilized by interaction with the mineral surface through polyvalent cation bridges (e.g. Ca2+ bridge) (Lützow et al. 2006; Takahashi and Dahlgren 2016; Wiesmeier et al. 2019).

Environmental and soil formation factors are considered to play an important role in controlling the persistence and stabilization of soil OM, through complex interactions with other factors including soil minerals, microbes and vegetation (Schmidt et al. 2011; Luo et al. 2016). Recent studies indicate the role of soil mineralogy as a key factor controlling OM stabilization (Heckman et al. 2009; Doetterl et al. 2015). As soil mineralogy is largely determined by the bedrocks and weathering processes, spatial heterogeneity in the bedrocks can induce differences in soil mineralogy and further impact the soil OM stabilization (Wattel-Koekkoek et al. 2003). A previous study in the same area of the present study confirmed that the distribution of SOC stocks depends on lithology (bedrocks) (Yang et al. 2018). The lithology dependent SOC distribution suggests that differences in OM stabilization can be expected to occur for soils with contrasting bedrocks.

The storage, turnover and stabilization of OM can differ substantially between the topsoil and the subsoil (Fontaine et al. 2007; Rumpel and Kögel-Knabner 2010; Batjes 2014). Vertical distribution of SOC is related to processed including OM input, decomposition, stabilization and downwards movement. These processed are potentially controlled by pedological processes driven by bedrocks (Rumpel and Kögel-Knabner 2010; Kaiser and Kalbitz 2012). Investigating the vertical distribution patterns of OM could yield a better understanding of the SOC distribution as controlled by the spatial distribution of the lithology in the Peruvian Andes.

Our present study aimed to explore the differences in SOC stocks between well-developed limestone soils (LSs) and acid igneous rock soils (ASs) in the Peruvian Andes, and to elucidate potential differences in OM stabilization mechanisms operating in these different lithologies. For this, selective extraction methods were applied in combination with bivariate and partial correlation analysis to identify functional fractions most likely responsible for OM stabilization.

Methods and materials

Site description

The study area was located to the west of the city of Cajamarca, Peru, with coordinates 7° 11′ S, 78° 35′ W. The area was on the continental watershed between the Atlantic and the Pacific Ocean, belonging to the Western Cordillera mountain chain of the Andes. The altitudes of our sampling region were between 3500 and 3720 m asl. The annual average temperature and precipitation were estimated as 9 °C and 1100 mm at an altitude of 3500 m asl, based on climate data of Station Porcon 2 (3510 m asl) and Station Cumbe Mayo (3410 m asl). The temperature was characterized by limited seasonal but large daily variations, whereas the majority of the precipitation occurred in wet seasons between October and April (Seijmonsbergen et al. 2010; Sánchez Vega et al. 2006).

The geological formations consist of a basement of folded Cretaceous marine sediments intruded and overlain by igneous rocks. The sediments include the formations of Cajamarca, Chulec-Calizas, Pariatambo, Farrat and Yumagual, with bedrocks of limestone, shale, marl and quartzite. The igneous bedrocks that belong to the San Pablo formation include intrusive granitic rocks and extrusive ignimbritic rocks (Reyes-Rivera 1980; Geo GPS Perú 2014).

The study area belongs to the Jalca (Sánchez Vega et al. 2005) or wet Puna phytoregion (Rolando et al. 2017b), a Neotropical alpine grassland ecosystem as a transition between humid Páramo to the north and dry Puna to the south. This region is characterized by large geodiversity and biodiversity. Significant human activities include cultivation and grazing, which cause land use change and potential degradation of vegetation. The land use pattern is characterized by rotations of cultivation, fallow and grazing, within a period of more than 2 years (Sánchez Vega et al. 2005; Tovar et al. 2013).

Soil sampling and classification

Soil samples were collected in July 2015, the dry season of this region. Figure 1 gives the information of six sampling plots characterized by contrasting bedrocks (lithology): three limestone plots and three acid igneous rock plots, respectively. The plots of acid igneous rocks were located in the transition zone between granite and ignimbrite. In addition to contrasting bedrocks, other factors related to soil formation were similar for each plot. The sampling plots were selected to meet the following three criteria: (1) located at gentle foot slopes with a stable environment for soil development, (2) having soils directly developed from the bedrocks rather than alluvial materials, and (3) being without crop production or intensive human disturbance. In addition, sampling next to forest patches was avoided to minimize the influence of soil acidification caused by the forest. Soil horizons were diagnosed by field observation. LSs had thick dark A horizons and argic B horizons above the C horizons, whereas ASs had dark vitric A horizons directly above C horizons or weathered bedrocks. Hereby we define the topsoil as A horizons and the subsoil as B horizons. Samples for the SOC stock determination were collected every 10 cm in duplicate with Kopecky rings (100 cm3) until the C horizons were reached. Samples for soil property analysis and selective extractions were collected in duplicate by diagnostic horizons, with each sample weighing 500–800 g. All samples were transferred into sealed plastic bags before transportation. Soil classification was based on the WRB (2014).

Sampling site description. LS limestone soil, AS soil on acid igneous rocks, n.d. not determined. The map of Peru on the left used the data from the ArcGIS Online World Topographic Map basemap (Esri 2013), whereas the data for the contour lines in the maps on the right was derived from Geo GPS Perú (2014)

Soil analysis

Soil samples for the SOC stock determination were freeze-dried. For these samples, soil moisture contents and bulk densities were measured by weighing samples before and after freeze-drying. Sub-samples of 5–10 g were milled to determine carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) concentrations. For samples used for soil property analysis, a porcelain mortar was applied to break large aggregates and passed through a 2 mm sieve, to separate fine earth fractions and gravels. The fine earth fractions were used for selective extractions and analyses of C and N contents, silt and clay contents, pH, cation exchange capacity (CEC) and phosphate retention. Total C and N contents were analyzed with an elemental analyzer (vario EL cube, elementar GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). Inorganic C (carbonate) contents were determined by measuring the produced CO2 after HCl treatment using the elemental analyzer equipped with a TIC module. As inorganic C contents were negligible in all the samples except for the C horizon of the profile LS2, the total C contents were equal to the OC concentrations. For the sample containing inorganic C (3.1% inorganic C, data not shown), the organic C content was calculated by subtracting the inorganic C content from the total C content. Silt plus clay (S + C) contents were determined using wet sieving through a 0.063 mm sieve after soil dispersion and OM removal using an H2O2 solution for 3 days. The S + C fractions obtained were further used for the clay content determination using a Sedigraph system (Sedigraph III Plus, Micromeritics, Norcross, USA). Soil pH was determined with a glass electrode in suspensions of soil material in demi-water (w:v = 1.5). Phosphate retention was measured using the colorimetry method mentioned by Blakemore et al. (1987). The percentage of volcanic glass was evaluated from the sand fractions by counting of glass particles using a 40 × microscope (Leica M420, macroscope, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Total SOC stocks were calculated by addition of the SOC stocks determined every 10 cm until the C horizon, using the equation:

In this equation, BDi = bulk density (g cm−3) of the layer i, Ci = SOC concentration (%) of the layer i, Si = stoniness (%) of layer i, Di = thickness (cm) of layer i.

A 0.2 M ammonium oxalate solution was used to extract poor-crystalline Fe and Al (Feo and Alo) at pH 3, using the procedure mentioned by Schwertmann (1964). A 0.1 M sodium pyrophosphate solution was applied to extract Fe, Al and C (Fep, Alp and Cp) from organo-metallic and organo-mineral complexes with minor Al from non-crystalline oxides (Wada 1989; Kaiser and Zech 1996; Kögel-Knabner et al. 2008). A citrate-dithionite solution was applied to extract pedogenic Fe (Fed) fractions, and the crystalline Fe was calculated by subtracting Feo from Fed (Holmgren 1967). A solution of 0.125 M BaCl2 was applied to determine the exchangeable cation contents (Caex, Mgex, Alex, Naex, Kex, Feex and Mnex) and calculate the CEC and the base saturation (BS) (Hendershot and Duquette 1986). Concentrations of Fe and Al in extracts of citrate-dithionite and pyrophosphate were determined with an Perkin Elmer AAnalist 400 Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, USA). Fe, Si and Al concentrations in the ammonium oxalate extracts and exchangeable cation (e.g. Caex, Mgex, Alex) concentrations in the BaCl2 extracts were determined with a Perkin Elmer Optima-8000 ICP OES (Perkin Elmer Corporation, Waltham, USA). In the BaCl2 extracts, the acidity was determined by titration with a 1.0 M NaOH solution, and the NH4 concentrations were measured by colorimetry at 670 nm with the hypochlorite and salicylate solutions (Krom 1980). The organic C concentrations in the pyrophosphate extracts were determined with a TOC-VCPH analyzer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan).

The mean weight diameter (MWD) was determined using the dry-sieving method. Briefly, air-dried soil samples (< 16 mm) were fractionated with four sieves (5, 2, 0.25 and 0.063 mm) for 20 s at 20 Hz using a horizontal shaker. All fractions > 2 mm were corrected for gravel contents. Bulk soil samples and the five sieved fractions were weighed, and the MWDs were calculated using the equation:

In this equation, xi max = maximum diameter (mm) of the fraction i, xi min = minimum diameter (mm) of the fraction i, wi = weight percent of the fraction i.

Macroaggregate stability was determined using a wet sieving method following a modified procedure of Amézketa (1999). Briefly, 5 g air-dried (40 °C) aggregates (> 2 mm) were placed on a 2 mm sieve with a horizontal shaker. The aggregates were fast-wetted by water showers and shaken at 20 Hz for 5 min. Materials remaining on the 2 mm sieve were air-dried at 40 °C. The weight percentages of the remaining materials to the original materials were used as the measure of macroaggregate stability. Microaggregate stability was measured using a particle size detector combined with an ultrasonic disperser (Amézketa 1999). Briefly, the size distribution of water stable microaggregates (< 0.25 mm) was determined using a sedigraph (Sedigraph III Plus, Micromeritics, Norcross, USA) with and without ultrasonic dispersion (10 s, 20 W) applied. The differences of microaggregate size distribution between dispersion and non-dispersion were used as the measure of microaggregate stability. The following equations were used to calculate respectively macroaggregate and microaggregate stability:

In the equations, stability (MA) = macroaggregate stability, W2mm = weight of fraction > 2 mm after wet sieving (g), Wall = weight of fraction before wet sieving (g), stability (MI) = microaggregate stability, xo i = average diameter (mm) of the fraction i without sonication, wo i = weight percent of the fraction i without sonication, xs i = average diameter (mm) of the fraction i with sonication, ws i = weight percent of the fraction i with sonication.

Statistics

All soil samples from A and B horizons were used for the statistical analyses. A principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to get an overview of the characteristics of LSs and ASs. The reliability of the PCA (sampling adequacy and sphericity) was checked using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test and the Bartlett’s test before the PCA applied. One-way ANOVAs were applied to compare differences in soil properties between LS-A horizons, LS-B horizons and AS-A horizons. For the post hoc comparison, a Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test was used. Pearson correlations were applied to test for bivariate correlations between different soil properties. Pearson partial correlations were applied to test correlations between two variables when the effects of one or more other variables (covariates) were removed. The objectives of using partial correlation were to compare potential differences in correlation patterns before and after: (1) the effects of the covariates removed (zero-order and partial correlations) and (2) effects between A and B horizons in the LSs removed.

When the assumption of data normality (checked by the Shapiro–Wilk test) was not met, a Kruskal–Wallis H test and Spearman (partial) correlations were applied to correspond to the one-way ANOVA and the Pearson (partial) correlations. When the assumption of variance homogeneity was violated, a Welch robust test and a Games–Howell test were applied instead of the one-way ANOVA and the LSD test. Results of these tests were reported together with original results (e.g. one-way ANOVA) as additional information. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 24.0 (SPSS Inc., USA). To reduce the probability of a Type II error, a significance level of p < 0.1 was used in addition to the commonly used levels of p < 0.05 and p < 0.01.

Results

Soil classification and soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks

The LSs were characterized by dark mollic A horizons, followed by underlying lighter B horizons with clay accumulation. In contrast, the ASs had dark A horizons directly above C horizons, with the presence of volcanic glass, high phosphate retention and Alo + 1/2Feo contents under 2% (Fig. 1). Combined with the pH, CEC and BS data, the LSs can be classified as either Haplic or Luvic Phaeozems, and the ASs were classified as Vitric Andosols (Fig. 1).

Total SOC stocks were significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the LSs (405 ± 42 Mg ha−1) compared to the ASs (226 ± 6 Mg ha−1, Fig. 2). The LSs had slightly higher SOC stocks compared to the ASs when accessed to 10 cm (P > 0.1), 30 cm (P > 0.1) and 50 cm (P < 0.1) (Fig. 2). The SOC contents accessed to all depths were significantly (P < 0.05) higher in the LSs compared to the ASs (P < 0.05), whereas soil bulk densities were not significantly different between the two soil types (Fig. 2). In addition, soil depths were larger in the LSs (61 cm) compared to the ASs (49 cm, Fig. 1).

Independent t tests of SOC stocks, SOC contents and bulk densities accessed to different soil depths and the entire soil profiles (mean ± SE, n = 3). Bulk density data was revised by gravel contents. LS limestone soil, AS acid igneous rock soil, SOC soil organic carbon. *Significant levels of P < 0.05

Overview of soil properties

Principal component 1 (PC1) and principal component 2 (PC2) explained 61.6% and 27.4% of the total variance in the PCA (Fig. 3). PC1 was positively loaded by exchangeable base cations, base saturation, pH, Fe fractions and silt plus clay contents, and was negatively loaded by Al fractions. PC2 had positive contributions from OM-related variables (C, Cp and N) and negative loadings of crystalline Fe oxides and pH (Fig. 3). LSs and the ASs were clearly separated along PC1. The LSs were associated with higher Fe fractions, exchangeable Ca and Mg, pH, CEC and base saturation, whereas the ASs were characterized by higher Al fractions (Fig. 3).

Principal component analysis (PCA) for each soil horizon. Figure above gives the factor loadings on the principal component 1 (PC1) and principal component 2 (PC2); figure below shows factor scores of horizons in limestone soils and acid igneous rock soils on the PC1 and PC2. Sampling adequacy and sphericity were checked using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test (0.616) and the Bartlett’s test (P < 0.001), which confirm the reliability of the PCA

The LSs had significantly higher SOC and Cp contents compared to the ASs in A horizons (P < 0.05, Table 1). The LSs also had higher Fe fractions (Fep, Feo, Fed-Feo), exchangeable base cations (Caex and Mgex), clay contents and silt plus clay contents than the ASs, but had lower Al fractions (Alp, Alo and Alex), Sio contents and molar contents of Fep + Alp (Table 1). Additionally, the LSs had significantly lower ratios of Fep/Feo and Alp/Alo but higher molar ratios of C/(Fep + Alp) compared to the ASs (P < 0.05, Table 1). For other soil properties, the LSs were characterized by higher CEC and pH values as well as larger aggregates sizes compared to the ASs (P < 0.05, Table 1). Furthermore, the LSs had more than 90% of the CEC comprised of Caex, whereas the ASs had Alex contents lower than 2.0 cmol kg−1 (Table 1). For the LSs, A horizons had significantly higher SOC, Cp, C–Cp, Fep, Alp and molar ratios of C/(Fep + Alp) compared to B horizons, whereas B horizons were characterized by coarser aggregates (larger) MWD compared to A horizons (P < 0.05, Table 1).

Correlations between variables in limestone soils (LSs)

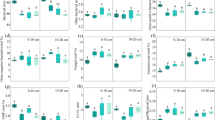

The SOC and Cp contents were positively correlated to Fep, Alo, Alp, Caex and silt plus clay contents, but were negatively correlated to Fed-Feo and clay contents (P < 0.1 for clay, P < 0.05 for others, Fig. 4). The mean weight diameters (MWDs) of aggregates were negatively correlated to OM-related variables (C, Cp and C–Cp), pyrophosphate fractions (Fep and Alp), exchangeable cations (Caex and Mgex) and clay contents (P < 0.1, Table 2). Macroaggregate stability was not correlated to OM-related variables or extracted fractions (Table 2), whereas microaggregate stability was negatively correlations with Cp, Alp and silt plus clay contents (P < 0.1, Table 2).

Correlations of soil organic carbon (SOC) and pyrophosphate extracted C (Cp) with extracted Fe, Al, Ca and Mg fractions, clay and silt plus clay contents. a–j Correlations between SOC and soil fractions, k–t correlations between Cp and soil fractions. Blue hollow square: LS-A horizons, blue solid square: LS-B horizons, red diamond: AS-A horizon. *,**Significant levels of P < 0.05 and 0.01, and P values between 0.05 and 0.1 are shown in bold without *. When the assumption of normality is violated, and P values of the non-parametric test are given in the bracket

When correlations with Caex were removed, OM-related variables (C, Cp and C-Cp) were positively correlated to Fep and Alp, except for the correlation between C-Cp and Alp (P < 0.05, Table 3). When correlations with Fep and Alp were removed, OM-related variables lost their correlations to Mgex, Alex and silt plus clay contents (Table 3). In contrast, C and Cp were still positively correlated to Caex (Table 3). When correlations with horizon were removed, correlations patterns between OM-related variables and other soil variables were not clearly changed compared to the zero-order correlations, except for correlations of C-Cp with Caex, Alp and Alex, as well as correlations of clay contents with C and Cp (Table 3). In addition, correlation patterns between OM-related variables and aggregate related variable (MWD and macroaggregate stability) were also not clearly changed when correlations with horizons were removed (Table 2).

Correlations between variables in acid igneous rock soils (ASs)

The SOC content was positively correlated to Feo, Fep, Alo, Alp and silt plus clay content at the significant level of P < 0.1, whereas Cp had positive correlations with the same soil properties at the significant level of P < 0.05 (Fig. 4). SOC and Cp were negatively correlated to clay content (P < 0.1), and were not correlated to Caex, Alex and Fed–Feo contents (Fig. 4). For soil aggregation, MWD was negatively correlated to Cp, Fep and Alp, and had a positive relationship with clay content (Table 2). In addition, aggregate stability had poor correlations with OM-related variables and other soil variables, with an exception of positives correlation between macroaggregate stability and clay content (Table 2).

Contents of C and Cp were positively correlated to silt plus clay content and pyrophosphate fractions (Fep and Alp) (P < 0.1, Table 3). However, when correlations with Fep and Alp were removed, C and Cp had no correlation with silt plus clay content. In contrast, when correlations with Caex was removed, C and Cp were still positively correlated with Fep and Alp (P < 0.05, Table 3).

Correlations between soil pH and other properties

Correlation between soil pH and other soil properties is presented in Table 4. Soil pH was positively correlated to Caex, Mgex, silt plus clay contents and clay contents (P < 0.1 for Mgex, P < 0.05 for others), but was negatively correlated to Alp only (Table 4). In contrast, no correlation was found between soil pH and OM-related variables (C, Cp and C-Cp, Table 4).

Discussion

OM stabilization in acid igneous rock soils (ASs)

The results indicate that OM in the ASs is stabilized by complexation and/or adsorption with/on Fe and Al (oxides), as underpinned by: (1) a large pyrophosphate extracted C fraction (high Cp/C ratios, Table 1), combined with (2) positive correlations of the pyrophosphate fractions (Fep and Alp) with OM-related variables (C, Cp and C-Cp) (Fig. 4; Table 3). Our interpretation is further supported by the robust correlations of Fep and Alp with OM-related variables after correlations with Caex and/or horizon were removed (Table 3). Similarly, soil OM stabilization in Andean soils is reported to be controlled by soil mineral adsorption through the formation of Fe/Al-OM complexes and/or Fe/Al oxides-OM associations in acid volcanic soils (Podwojewski et al. 2002; Buytaert et al. 2006; Tonneijck et al. 2010), as well as in soils formed on sedimentary rocks including limestones (Egashira et al. 1997).

It is unlikely that OM is stabilized by adsorption on clay minerals, given the negative correlations of clay content with SOC and Cp contents (Fig. 4d, n). This can be attributed to the overall coarse soil texture that leaves only a small clay fraction (Table 1 and Table S1). Similarly, Tonneijck et al. (2010) also reported that OM stabilization was not controlled by clay contents in the Ecuadorian volcanic soils. Aggregate size or aggregate stability was not the factor controlling OM stabilization because of the negative correlations between OM-related variables and MWD and the absence of correlations between OM-related variables and aggregate stability (Table 2). Heckman et al. (2014) also found that OM stabilization was not controlled by aggregate stability. They further explained this by the lack of relationship between aggregate stability and capability of aggregates to protect OM (Heckman et al. 2014). Again, the poor controls of soil aggregates on OM stabilization can be explained by the coarse texture and low clay contents in the ASs (Table 1), which inhibit aggregate formation (Bronick and Lal 2005). Ca2+ and Mg2+ bridges were not found to be OM stabilization agents, as indicated by their poor correlations with OM-related variables, which can be attributed to the low pH in the ASs (Table 1; Fig. 4). In acidic volcanic soils, OM is reported to be stabilized by adsorption on the surfaces of allophane and allophane-like minerals, as well as by limited microbial activities due to Al toxicity (Parfitt 2009; Tonneijck et al. 2010; Takahashi and Dahlgren 2016). However, no evidence indicates that OM was stabilized by adsorption on allophane or allophane-like minerals in the ASs. This is supported by the high ratios of Alp/Alo (Table 1) that indicate the ASs are non-allophanic soils (Dümig et al. 2008). In addition, Al toxicity is not likely to promote OM stabilization in the studied soils since the Alex contents always remained under the toxic level of 2 cmol kg−1. This is further corroborated by the poor correlations between Alex and OM-related variables (Fig. 2; Table 1).

OM stabilization in limestone soils (LSs)

Similar to the ASs, our results suggest that OM stabilization in the LSs is also controlled by complexation and/or adsorption with/on Fe and Al (oxides). This is supported by the positive correlations between the pyrophosphate fractions and OM-related variables (Fig. 4; Table 3), as well as their robust correlations after the correlations with Caex and/or horizon removed (Table 3). The OM stabilization in the LSs is unlikely explained by crystalline Fe (Fed–Feo) or clay contents because of their negative correlations (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the OM-related variables lost their negative correlations with clay contents after correlations with horizon were removed (Table 3). This suggests that the negative correlations might be explained by the effects of soil depths. Surprisingly, no or a negative correlation was observed between aggregate stability and OM-related variables, and between MWD and OM-related variables, although the LSs have high Caex contents and larger aggregates (Table 1). This suggests that aggregate size or aggregate stability is not likely to control OM stabilization in the LSs.

In addition to Fe and Al (oxides), Ca-related stabilization mechanisms likely play a significant role in OM stabilization in the LSs. This observation is supported by: (1) the high Caex/CEC ratios (0.94) in the LSs (Table 1), (2) the positive correlations between Caex and OM-related variables (Fig. 4), and (3) robust correlations between Caex and OM-related variables after correlations with Fep, Alp and horizon were removed (Table 3). The proposed Ca-related stabilization mechanisms are: (1) Ca2+ bridges between mineral surface and OM (Lützow et al. 2006; Wiesmeier et al. 2019) and (2) improved soil structure through the presence of Ca2+ bridges, which can potentially stabilize OM by physical protection within aggregates (Muneer and Oades 1989; Bronick and Lal 2005). As no clear evidence suggests that aggregation promotes OM stabilization in the LSs as previously explained (Table 2), the adsorption of OM on mineral surfaces via Ca2+ bridges is likely an important OM stabilization mechanism in the LSs.

The OM stabilization controlled by Ca2+ bridging is further corroborated by the observed molar ratios of C/(Fep + Alp) (Table 1). In general, complexation and adsorption sites on the Fe and Al (oxides) have a maximum capacity to stabilize OM. The maximum capacity can be quantified using an indicator of molar ratios of C/(Fep + Alp). Summarized from different studies, molar ratios of C/(Fep + Alp) between 5 and 10 were reported as indicative of saturation of the complexation and adsorption sites on the Fe and Al (oxides) (Boudot et al. 1989; Oades 1989; Schwesig et al. 2003; Masiello et al. 2004; Jansen et al. 2011). The LSs had much higher C/(Fep + Alp) ratios (52.6 and 32.4 for A and B horizon, Table 1) compared to the saturation level (5–10), which suggests Fe and Al (oxides) are not likely the only stabilization agents. As OM associated with mineral surfaces is the major fraction of bulk soil OM (Golchin et al. 1994; Cerli et al. 2012), Ca2+ bridges are likely important to stabilize the OM that is not stabilized by Fe and Al (oxides). This can be further supported by that the LSs have lower ratios of Fep/Feo and Alp/Alo than the ASs (Table 1). The lower ratios in the LSs suggested less saturated complexation or adsorption sites on Fe and Al (oxides) (Kögel-Knabner et al. 2008), and the less saturated sites are likely to be explained by Ca2+ bridges also contributing to the OM stabilization. In contrast, the ASs had lower ratios of C/(Fep + Alp) (16.3) and higher ratios of Fep/Feo and Alp/Alo compared to the LSs (Table 1), which suggests that Fe and Al (oxides) dominate the OM stabilization in the ASs.

Unlike the ASs, the LSs are characterized by a B horizon underlying A horizons in each plot. However, OM stabilization mechanisms were not clearly different between A and B horizons, as indicated by (1) similar ratios of Fep/Feo, Cp/C and Caex/CEC between the A and B horizons, and (2) similar (partial) correlation patterns before and after the correlations with horizon were removed (Tables 1, 3). Although A and B horizons of the LSs share similar OM stabilization mechanisms, Fep, Alp and Caex contents decreased with soil depth (Table 1 and Table S1). The decreased Fep, Alp and Caex contents together with declined C input with soil depth, occurrence of microbial degradation and downwards movement of the OM regulate the vertical distribution of SOC contents and C/N ratios in the LSs (Fontaine et al. 2007; Rumpel and Kögel-Knabner 2010; Kaiser and Kalbitz 2012).

SOC stocks explained by OM stabilization

The SOC stocks in both LSs and ASs were also higher compared to the global average SOC stocks reported by Lal (2004) and Batjes (2014). For other alpine Andean soils, Tonneijck et al. (2010) and Farley et al. (2004) reported higher SOC stocks in Ecuadorian grasslands with wetter climate compared our soils. In contrast, lower SOC stocks were reported in Bolivia and Southern Peru with drier climate (Zimmermann et al. 2009; Muñoz et al. 2016; Rolando et al. 2017a). When compared to other alpine soils, our soils also have higher SOC stocks (e.g. Garcia-Pausas et al. 2007; Zhu et al. 2015).

The results showed higher total SOC stocks in the LSs compared to the ASs (Fig. 2). The higher total SOC stocks can be explained by the higher SOC contents and deeper soil profiles for the LSs (Figs. 1, 2). In contrast, bulk densities were not significantly different between LSs and ASs (Fig. 2), which indicates that the differences in SOC stocks are not likely controlled by soil bulk density. The higher SOC contents in the LSs is likely attributed to LSs having OM stabilization mechanisms related to Ca2+ bridges in addition to stabilization related to complexation with and/or adsorption on Fe and Al (oxides) that occurs in both LSs and ASs. More specifically, if Fe and Al (oxides) are assumed to be the only OM stabilization agents, the LSs should have lower SOC contents due to their smaller molar Fep + Alp contents compared to the ASs (Table 1). Obviously, this does not match the higher SOC stocks and contents in the LSs (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Thus, the higher SOC stocks in the LSs can be explained by their higher SOC contents induced OM stabilization controlled by Ca2+ bridges. This is supported by that: (1) Ca2+ bridges are not an OM stabilization agent in the ASs and (2) OM stabilization in the LSs is poorly controlled by clay contents, crystalline Fe oxides, aggregate size or aggregate stability. In contrast, the small SOC stocks and contents in the ASs are likely restricted by OM stabilization being controlled by interactions with Fe and Al (oxides) only. This is further corroborated by their higher ratios Fep/Feo and Alp/Alo (Table 1), which indicate their more-saturated adsorption and/or complexation sites of the Fe and Al (oxides) compared to the LSs (Kögel-Knabner et al. 2008). The adsorption and/or complexation sites of the ASs, which can stabilize less OM compared to the LSs, are likely to be more saturated with OM under similar C input levels compared to the LSs due to their similar vegetation.

OM stabilization driven by soil pH

In our study, although SOC contents are not clearly controlled by soil pH, the underlying OM stabilization mechanisms are clearly regulated by soil pH. This is supported by the lack of correlations between pH and OM-related variables, and the correlations between pH and Fep, Alp and Caex fractions (Table 4). The positive correlations between pH and Caex and the negative correlation between pH and Alp (Table 4) suggests that Ca2+ bridges are more important in OM stabilization at higher pH while Al (oxides) is more important at lower pH. The shifts in OM stabilization mechanisms between LSs and ASs coincide with the general view that soil pH plays a fundamental role in controlling soil OM stabilization mechanisms (Clarholm and Skyllberg 2013; Rowley et al. 2018). In general, the formations of Fe- and Al-OM complexation as well as Al3+ toxicity are reported as the dominant OM stabilization mechanisms in soils with low pH (Dümig et al. 2008; Tonneijck et al. 2010; Takahashi and Dahlgren 2016). For neutral or alkaline soils, Fe and Al oxides, and base cation bridges are reported as stabilization mechanisms (Masiello et al. 2004; Kaiser et al. 2011; Porras et al. 2017). Similar to our results, Masiello et al. (2004), Heckman et al. (2009) and Kaiser et al. (2011) reported a shift in soil OM stabilization mechanisms from controlled by Fe and Al (oxides) to that controlled by Ca-related mechanisms due to increasing soil pH. Consistent with these studies, our results highlight the shift from OM stabilization dominated by interacting with Fe and Al (oxides) to that controlled by Ca2+ bridges with increasing soil pH values.

Clarholm and Skyllberg (2013) reported soil pH values between 6.2 and 6.8 as a ‘window of opportunity’, in which OM stabilization controlled by Fe, Al and Ca is not strong. The ‘window of opportunity’ allows for weak OM stabilization and higher OM degradation. However, our results do not support the ‘window of opportunity’ because the LSs fall into the window but have highly stabilized OM. A possible explanation is that the OM stabilization is still controlled by OM association with Fe oxides when the LSs falls into the window. The explanation is supported by the robust correlations between OM-related variables and Fep in the LSs (Fig. 4; Table 3). The findings suggest that more research is needed to unravel the effects of soil pH on OM stabilization controlled by Fe, Al and Ca.

Conclusions

The results indicate that lithology is the key factor controlling soil OM stabilization mechanisms in the studied soils of the Northern Peruvian Andes. In the ASs, OM stabilization is dominated by OM complexation and/or adsorption with Fe and Al (oxides). In the LSs, OM stabilization is controlled by OM adsorption on mineral surfaces through Ca2+ bridges in addition to interactions of OM with Fe and Al (oxides). The LSs had significantly higher SOC stocks than the ASs, which can be explained by their higher SOC contents due to the presence of Ca-related OM stabilization mechanisms. Our results highlighted that the shifts in OM stabilization mechanisms from interacting with Fe and Al (oxides) to interacting with Ca2+ bridges are controlled by increasing soil pH values. This suggests that the OM stabilization mechanisms controlled by soil pH in the Peruvian Andes are similar to the general findings in other soils.

The study indicates that lithology has to be considered for further studies on SOC stocks and the underlying OM stabilization in the Peruvian Andes, because of its important role in controlling OM–mineral interactions. However, it is surprising that OM-related variables were not positively correlated to aggregate parameters in the LSs, which have good soil structure and high Caex contents. Further studies could apply methods like density fractionation with ultrasonic treatments and incubation with aggregate destruction to unravel the role of aggregates in soil OM stabilization in the Peruvian Andes.

References

Amézketa E (1999) Soil aggregate stability: a review. J Sustain Agric 14:83–151. https://doi.org/10.1300/J064v14n02

Batjes NH (2014) Total carbon and nitrogen in the soils of the world. Eur J Soil Sci 65:1. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.12120

Blakemore LC, Searle PL, Daly BK (1987) Methods for chemical analysis of soils. N. Z. Soil Bureau Scientific Report 80, Soil Bureau, Lower Hutt, pp 38–41

Boudot JP, Bel Hadj Brahim A, Steiman R, Seigle-Murandi F (1989) Biodegradation of synthetic organo-metallic complexes of iron and aluminium with selected metal to carbon ratios. Soil Biol Biochem 21:961–966. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(89)90088-6

Bronick CJ, Lal R (2005) Soil structure and management: a review. Geoderma 124:3–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2004.03.005

Buytaert W, Cuesta-Camacho F, Tobón C (2011) Potential impacts of climate change on the environmental services of humid tropical alpine regions. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 20:19–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00585.x

Buytaert W, Deckers J, Wyseure G (2006) Description and classification of nonallophanic Andosols in south Ecuadorian alpine grasslands (páramo). Geomorphology 73:207–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2005.06.012

Cerli C, Celi L, Kalbitz K et al (2012) Separation of light and heavy organic matter fractions in soil—testing for proper density cut-off and dispersion level. Geoderma 170:403–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2011.10.009

Clarholm M, Skyllberg U (2013) Translocation of metals by trees and fungi regulates pH, soil organic matter turnover and nitrogen availability in acidic forest soils. Soil Biol Biochem 63:142–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.03.019

Doetterl S, Stevens A, Six J et al (2015) Soil carbon storage controlled by interactions between geochemistry and climate. Nat Geosci 8:780–783. https://doi.org/10.1038/NGEO2516

Dümig A, Schad P, Kohok M et al (2008) A mosaic of nonallophanic Andosols, Umbrisols and Cambisols on rhyodacite in the southern Brazilian highlands. Geoderma 145:158–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2008.01.013

Dungait JAJ, Hopkins DW, Gregory AS, Whitmore AP (2012) Soil organic matter turnover is governed by accessibility not recalcitrance. Glob Chang Biol 18:1781–1796. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02665.x

Egashira K, Uchida S, Nakashima S (1997) Aluminum-humus complexes for accumulation of organic matter in black-colored soils under grass vegetation in Bolivia. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 43:25–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380768.1997.10414711

Esri (2013) Topographic basemap. World Topographic Map. https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=30e5fe3149c34df1ba922e6f5bbf808f. Accessed May 2019

Farley KA, Kelly EF, Hofstede RGM (2004) Soil organic carbon and water retention after conversion of grasslands to pine plantations in the Ecuadorian Andes. Ecosystems 7:729–739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-004-0047-5

Fontaine S, Barot S, Barré P et al (2007) Stability of organic carbon in deep soil layers controlled by fresh carbon supply. Nature 450:277–280. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06275

Gang C, Zhou W, Chen Y et al (2014) Quantitative assessment of the contributions of climate change and human activities on global grassland degradation. Environ Earth Sci 72:4273–4282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-014-3322-6

Garcia-Pausas J, Casals P, Camarero L et al (2007) Soil organic carbon storage in mountain grasslands of the Pyrenees: effects of climate and topography. Biogeochemistry 82:279–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-007-9071-9

Geo GPS Perú (2014) GEO GPS PERÚ: Base de datos Perú-Shapefile-*.shp-MINAM-IGN-Límites Políticos. https://www.geogpsperu.com/2014/03/base-de-datos-peru-shapefile-shp-minam.html. Accessed July 2017

Golchin A, Oades JM, Skjemstad JO, Clarke P (1994) Study of free and occluded particulate organic matter in soils by solid state 13c NMR spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy. Soil Res 32:285–309. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR9940285

Heckman K, Throckmorton H, Clingensmith C et al (2014) Factors affecting the molecular structure and mean residence time of occluded organics in a lithosequence of soils under ponderosa pine. Soil Biol Biochem 77:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.05.028

Heckman K, Welty-Bernard A, Rasmussen C, Schwartz E (2009) Geologic controls of soil carbon cycling and microbial dynamics in temperate conifer forests. Chem Geol 267:12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2009.01.004

Hendershot WH, Duquette M (1986) A simple barium chloride method for determining cation exchange capacity and exchangeable cations. Soil Sci Soc Am J 50:605–608

Holmgren GG (1967) A rapid citrate-dithionite extractable iron procedure. Soil Sci Soc Am J 31:210–211

Hribljan JA, Suárez E, Heckman KA et al (2016) Peatland carbon stocks and accumulation rates in the Ecuadorian páramo. Wetl Ecol Manag 24:113–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-016-9482-2

Jansen B, Tonneijck FH, Verstraten JM (2011) Selective extraction methods for aluminium, iron and organic carbon from montane volcanic ash soils. Pedosphere 21:549–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0160(11)60157-4

Kaiser K, Kalbitz K (2012) Cycling downwards—dissolved organic matter in soils. Soil Biol Biochem 52:29–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.04.002

Kaiser K, Zech W (1996) Defects in estimation of aluminum in humus complexes of podzolic soils by pyrophosphate extraction. Soil Sci 161:452–458

Kaiser M, Walter K, Ellerbrock RH, Sommer M (2011) Effects of land use and mineral characteristics on the organic carbon content, and the amount and composition of Na-pyrophosphate-soluble organic matter, in subsurface soils. Eur J Soil Sci 62:226–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2010.01340.x

Kleber M, Eusterhues K, Keiluweit M et al (2015) Mineral-organic associations: formation, properties, and relevance in soil environments. Elsevier, New York

Kögel-Knabner I, Guggenberger G, Kleber M et al (2008) Organo-mineral associations in temperate soils: integrating biology, mineralogy, and organic matter chemistry. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 171:61–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.200700048

Krom MD (1980) Spectrophotometric determination of ammonia: a study of a modified Berthelot reaction using salicylate and dichloroisocyanurate. Analyst 105:305–316

Lal R (2004) Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 304:1623–1627

Lehmann J, Kleber M (2015) The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 528:60–68. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16069

Luo Y, Ahlström A, Allison SD et al (2016) Toward more realistic projections of soil carbon dynamics by Earth system models. Global Biogeochem Cycles. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GB005239.Received

Lützow MV, Kogel-Knabner I, Ekschmitt K et al (2006) Stabilization of organic matter in temperate soils: mechanisms and their relevance under different soil conditions—a review. Eur J Soil Sci 57:426–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2006.00809.x

Masiello CA, Chadwick OA, Southon J et al (2004) Weathering controls on mechanisms of carbon storage in grassland soils. Global Biogeochem Cycles 18:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GB002219

Muneer M, Oades JM (1989) The role of Ca-organic interactions in soil aggregate stability. I. Laboratory studies with 14C-glucose, CaCO3 and CaSO4·2H2O. Aust J Soil Res 27:389–399

Muñoz C, Cruz B, Rojo F et al (2016) Temperature sensitivity of carbon decomposition in soil aggregates along a climatic gradient. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 16:461–476. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-95162016005000039

Muñoz García MA, Faz Cano A (2012) Soil organic matter stocks and quality at high altitude grasslands of Apolobamba, Bolivia. CATENA 94:26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2011.06.007

Oades JM (1989) An introduction to organic matter in mineral soils. In: Dixon JB, Weed SB (eds) Minerals in soil environments. Soil Science Society of America, Madison, pp 89–159

Parfitt RL (2009) Allophane and imogolite: role in soil biogeochemical processes. Clay Miner 44:135–155. https://doi.org/10.1180/claymin.2009.044.1.135

Podwojewski P, Poulenard J, Zambrana T, Hofstede R (2002) Overgrazing effects on vegetation cover and properties of volcanic ash soil in the pàramo of Llangahua and al Esperanza (Tungurahua, Ecuador). Management 18:45–55. https://doi.org/10.1079/SUM2001100

Porras RC, Hicks Pries CE, McFarlane KJ et al (2017) Association with pedogenic iron and aluminum: effects on soil organic carbon storage and stability in four temperate forest soils. Biogeochemistry 133:333–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-017-0337-6

Reyes-Rivera L (1980) Geología de los Cuadrángulos de Cajamarca, San Marcos y Cajabamba (sheets 15f, 15g y 16g). Carta Geológica Nacional Peru. Instituto Geología Minera y Metalúrgica, Boletín 31, serie A. Lima

Rolando JL, Dubeux JC, Perez W et al (2017a) Soil organic carbon stocks and fractionation under different land uses in the Peruvian high-Andean Puna. Geoderma 307:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.07.037

Rolando JL, Turin C, Ramírez DA et al (2017b) Key ecosystem services and ecological intensification of agriculture in the tropical high-Andean Puna as affected by land-use and climate changes. Agric Ecosyst Environ 236:221–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.12.010

Rowley MC, Grand S, Verrecchia ÉP (2018) Calcium-mediated stabilisation of soil organic carbon. Biogeochemistry 137:27–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-017-0410-1

Rumpel C, Kögel-Knabner I (2010) Deep soil organic matter—a key but poorly understood component of terrestrial C cycle. Plant Soil 338:143–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-010-0391-5

Sánchez Vega I, Cabanillas Soriano M, Miranda Leiva A, Poma Rojas W, Díaz Navarro J, Terrones Hernández F, Bazán Zurita H (2005) La jalca: el ecosistema frio del noroeste peruano, fundamentos biologicos y ecologicos. Minera Yanacocha, Cajamarca

Sánchez Vega I, Dillon MO (2006) Jalcas. In: Moraes M, Øllgaard Kvist LP, Borchsenius F, Balslev H (eds) Botanica Economica de los Andes Centrales. Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, La Paz, pp 77–90

Schmidt MWI, Torn MS, Abiven S et al (2011) Persistence of soil organic matter as an ecosystem property. Nature 478:49–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10386

Schrumpf M, Kaiser K, Guggenberger G et al (2013) Storage and stability of organic carbon in soils as related to depth, occlusion within aggregates, and attachment to minerals. Biogeosciences 10:1675–1691. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-1675-2013

Schwertmann U (1964) Differenzierung der Eisenoxide des Bodens durch Extraktion mit Ammoniumoxalat-Lösung. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 105:194–202

Schwesig D, Kalbitz K, Matzner E (2003) Effects of aluminium on the mineralization of dissolved organic carbon derived from forest floors. Eur J Soil Sci 54:311–322. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.00523.x

Seijmonsbergen AC, Sevink J, Cammeraat LH, Recharte J (2010) A potential geoconservation map of the Las Lagunas area, northern Peru. Environ Conserv 37:107–115. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892910000408

Six J, Conant RT, Paul EA, Paustian K (2002) Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant Soil 241:155–176. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016125726789

Sollins P, Homann P, Caldwell BA (1996) Stabilization and destabilization of soil organic matter: mechanisms and controls. Goederma 74:65–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7061(96)00036-5

Takahashi T, Dahlgren RA (2016) Nature, properties and function of aluminum-humus complexes in volcanic soils. Geoderma 263:110–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2015.08.032

Tonneijck FH, Jansen B, Nierop KGJ et al (2010) Towards understanding of carbon stocks and stabilization in volcanic ash soils in natural Andean ecosystems of northern Ecuador. Eur J Soil Sci 61:392–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2010.01241.x

Tovar C, Seijmonsbergen AC, Duivenvoorden JF (2013) Monitoring land use and land cover change in mountain regions: an example in the Jalca grasslands of the Peruvian Andes. Landsc Urban Plan 112:40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.12.003

Wada K (1989) Allophane and imogolite. In: Dixon JB, Weed SB (eds) Minerals in soil environments. Soil Science Society of America, Madison, pp 1051–1087

Wattel-Koekkoek EJW, Buurman P, Van Der Plicht J et al (2003) Mean residence time of soil organic matter associated with kaolinite and smectite. Eur J Soil Sci 54:269–278. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.00512.x

Wiesmeier M, Urbanski L, Hobley E et al (2019) Soil organic carbon storage as a key function of soils—a review of drivers and indicators at various scales. Geoderma 333:149–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.07.026

WRB IWG (2014) World reference base for soil resources 2014. International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps. FAO, Rome

Yang S, Cammeraat E, Jansen B et al (2018) Soil organic carbon stocks controlled by lithology and soil depth in a Peruvian alpine grassland of the Andes. CATENA 171:11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2018.06.038

Zhu P, Chen R, Song Y et al (2015) Effects of land cover conversion on soil properties and soil microbial activity in an alpine meadow on the Tibetan Plateau. Environ Earth Sci 74:4523–4533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-015-4509-1

Zimmermann M, Meir P, Silman MR et al (2009) No differences in soil carbon stocks across the tree line in the Peruvian Andes. Ecosystems 13:62–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-009-9300-2

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the local community of Sexemayo and Chetilla for the necessary working permit in Cajamarca, Peru. We thank the help of Chiara Cerli, John Visser, Leo Hoitinga, Leen de Lange and Peter Serné for the lab work, as well as the support from Emiel van Loon for statistical analyses. We also thank the Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics (IBED) and the China Scholarship Council (CSC) for funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, S., Jansen, B., Kalbitz, K. et al. Lithology controlled soil organic carbon stabilization in an alpine grassland of the Peruvian Andes. Environ Earth Sci 79, 66 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-019-8796-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-019-8796-9