Abstract

Background

Psychosocial stress is a major health threat in modern society. Short-term effects of stress on health behaviors have been identified as relevant processes. This article examines the moderating effect of dispositional self-control on the association between stress at work and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) after work.

Methods

In a sample of 153 police officers (103 men, 50 women, mean age = 39.3 ± 10.4 years), daily occupational stress and hours worked were assessed via ecological momentary assessment (smartphone-based single item) in real-life. Dispositional self-control was assessed via an online questionnaire, whereas physical activity was assessed via accelerometry. A hierarchical linear regression analysis was performed to test main and interaction effects.

Results

Bivariate correlations showed that perceived stress at work was positively correlated with hours worked (r = 0.24, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.09, 0.39]), whereas a negative association was found with dispositional self-control (r = −0.27, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.41, −0.12]). After-work MVPA was neither associated with stress at work nor with dispositional self-control. The regression analysis yielded no significant interaction between stress at work and dispositional self-control on after-work MVPA.

Conclusion

Using a state-of-the-art ecological momentary assessment approach to assess feelings of stress in real-life, stress at work did not seem to impact after-work MVPA in police officers. More research is needed to establish whether this finding is specific to police officers or whether it can be generalized to other populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psychosocial stress is a major health threat in modern society (Gerber & Schilling, 2018; Tomitaka et al., 2019). As highlighted by the American Psychological Association (2017), the occupational environment constitutes one of the most significant sources of stress. The process linking psychosocial stress to disease is considered to be highly complex and, to date, not fully understood (Cohen, Janicki-Deverts, & Miller, 2007). While long-term (up to years) stress is related to negative health outcomes (Elfering et al., 2005), evidence suggests that this relationship can in part be explained by short-term (day-level) effects of stress on health behaviors (Chandola et al., 2008; Slopen et al., 2013; Sonnentag & Jelden, 2009). In this article, we explicitly address these possible short-term pathways of occupational stress, and their potential effects on one specific health behavior, namely physical activity (Fransson et al., 2012; Kivimäki et al., 2013; Kouvonen et al., 2013).

The importance of physical activity for health is well acknowledged (Huang et al., 2021a), whereby participation in regular physical activity is associated with improved health and decreased mortality (Ekelund, Dalene, Tarp, & Lee, 2020; Mora, Cook, Buring, Ridker, & Lee, 2007). Therefore, the World Health Organization recommends certain levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per week (Bull et al., 2020). Evidence further suggests that physical inactivity is positively related to a variety of diseases and higher risks for premature death (Huang et al., 2021b). Research has also shown that personal awareness of these health effects is only a weak predictor of people’s intention to be (or to become) physically active and/or their actual physical activity behavior (Faries, 2016; Rhodes & Courneya, 2003). As introduced above, research has shown that psychosocial stress at work predicts lowered execution of healthy behaviors, such as physical activity (Chandola et al., 2008). Consequently, the negative effects of psychosocial stress on health are presumed to be, at least partially, explained by changes in health behaviors, namely lowered levels of physical activity.

The resource model of self-control is one often used theoretical model to explain the relationship between increased psychosocial stress and changes in health behaviors (Baumeister, Heatherton, & Tice, 1994; Englert, 2016; Hagger, Wood, Stiff, & Chatzisarantis, 2010; Sax, 1997). Within this model, it is assumed that stress reduces the available resources for self-regulatory control, resulting in difficulties to maintain healthy behaviors (Baumeister, Vohs, & Tice, 2007). Prior investigations have shown that trait self-control is associated with higher engagement in physical activity independently of people’s stress levels (Kinnunen, Suihko, Hankonen, Absetz, & Jallinoja, 2012; Wills, Isasi, Mendoza, & Ainette, 2007). More importantly, research has also demonstrated that trait self-control facilitates maintenance of healthy behaviors (e.g., nonsmoking, healthy eating, physical activity) if people are exposed to stress (Crescioni et al., 2011; de Ridder, Lensvelt-Mulders, Finkenauer, Stok, & Baumeister, 2012; Martin Ginis & Bray, 2010; Oaten & Cheng, 2006).

Most prior research has focused on the question whether physical activity (and high levels of cardiorespiratory fitness) has the potential to mitigate some of the deleterious health effects associated with high stress levels (Gerber, Börjesson, Ljung, Lindwall, & Jonsdottir, 2016; Gerber & Pühse, 2009; Gerber et al., 2019; Klaperski, 2018; Park & Iacocca, 2014). Therefore, investigating the reciprocal effect of stress on PA as a health behavior is an important, yet understudied field of research (Gerber, Fuchs, & Pühse, 2013; Gerber et al., 2015; Isoard-Gautheur, Ginoux, Gerber, & Sarrazin, 2019; Stults-Kolehmainen & Sinha, 2013). Moreover, modern technologies facilitate the assessment of stress in naturalistic environments beyond retrospective self-reports (Kasten & Fuchs, 2018). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is increasingly used in sport and exercise science (Reichert et al., 2020). Herein, portable devices can assess multiple experiences in realistic contexts, and in almost real-time, rather than necessitating long-term recall (Reichert et al., 2020; Stone & Shiffman, 1994). This is especially important in the assessment of affective–emotional processes, which have been shown to be strongly influenced by recall bias, e.g., by duration neglect (Fredrickson & Kahneman, 1993). Stress experiences are emotionally represented phenomena which further highlights the advantage of EMA in capturing experiences within the contexts they are actually situated in (Kasten & Fuchs, 2018; Reichert et al., 2020). In the current study we applied EMA to assess stress in real-life and close to real-time in order to assess stress experiences within personally relevant contexts and with minimized recall bias (Reichert et al., 2020). Applying the theoretical assumptions of the resource model of self-control, we expect that on a day with more stress at work, participants have to rely on self-control in order to engage in physical activity after completion of work.

An occupation which is particularly known for encountering several acute and chronic stressors is policing (Brown & Campbell, 1990; McCreary & Thompson, 2006). While police officers are acknowledged to start their career in very good health, some may develop severe health problems due to the cumulative impact of stress experienced during the course of their career (Waters & Ussery, 2007). Reports on stress-related health behaviors include smoking as well as alcohol consumption (McCarty, Aldirawi, Dewald, & Palacios, 2019). As stated by Buckingham, Morrissey, Williams, Price, and Harrison, (2020), policing has become increasingly sedentary. In addition, a study by Ramey et al., (2014) showed that police officers are more active on days off duty.

Research questions and hypothesis

The main purpose of the present study was to find out whether stress at work during the day influenced device-based measured levels of MVPA after work in police officers. We also examined whether this relationship was moderated by dispositional self-control. Based on the literature presented above (Fransson et al., 2012), we hypothesized that individuals who experienced more stress during their working day would engage in less MVPA after work (Hypothesis 1). Moreover, we expected that this association would be moderated by participants’ dispositional self-control (Oaten & Cheng, 2006), in the sense that among individuals who experienced high levels of occupational stress, those who reported higher self-control would be more able to maintain their MVPA levels than their counterparts with low self-control (Hypothesis 2A). Among participants who experienced low occupational stress, we assumed that after-work MVPA levels would be similar among participants with low vs. high levels of dispositional self-control (Hypothesis 2B). These relationships are expected to be observable at interindividual level.

Methods

Study design, participants and procedures

The sample was recruited from a police force in the canton Basel, a German-speaking city in Switzerland. All officers (N = 980, 290 women, 690 men) were invited to participate in a comprehensive health check, which was part of a larger project, described previously (Schilling et al., 2019). Out of all 980 information recipients, 201 voluntarily participated in the study (20.5% response rate). Data were assessed between December 2017 and April 2018. A personalized health profile was given to each officer after the completion of the data assessment as an incentive for participation. Moreover, all officers had the opportunity to participate in a voluntary lifestyle coaching after the health check. Data extracted for the present study include anthropometry, cardiorespiratory fitness test, actigraphy, smartphone-based assessment of work-related stress experiences, as well as an online survey on dispositional self-control and work stress. All participants provided written informed consent before data assessment. All procedures were in line with the ethical principles described in the Helsinki Declaration, and approval was obtained for the study by the local ethics committee (EKNZ: Project ID: 2017-01477).

Measures

Stress at work.

The smartphone-based assessment of work-related feelings of stress started the day prior to the assessment of one entire workday. This procedure was chosen to assess one entire workday for every participant. Data from this single workday were then used for data analysis. The sample limits of this entire workday depended on participants’ shift schedule. These sample limits ranged from 12 am to 7 pm for shift workers, and 9 am to 5 pm for office workers. The same time windows were used to distinguish between MVPA at vs. after work (end of work until 12 pm that same day).

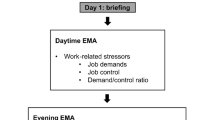

Stress at work was assessed in real-life via EMA. Each time the participants were contacted, they were asked to respond to a set of questions on a smartphone (Moto G, 3rd Generation) via MovisensXS (movisens GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany), an app for Android smartphones. MovisensXS offers a web-based software solution for question settings, sampling contingents, and management of participants; at a later stage, the software processes and prepares data output for analysis. Three sets of questions were triggered in the morning, during the workday, and in the evening. The present paper considers the workday set, which will now be described in detail: The workday set sampled between 12 am and 7 pm for all shift workers (matching their shift schedule) and between 9 am and 5 pm for regular office workers. All sets were time-triggered once per hour with a random appearance of ±15 min. Therefore, participants received up to 8 prompts during their workday. At least one prompt had to be answered to be regarded as valid for data analysis. The participants responded to an alarm (tone and vibration), which otherwise would repeat every 5 min; if participants did not complete the survey after 15 min, the current assessment was closed. In addition, participants had the opportunity to postpone the first alarm for up to 15 min. In this case, only one further alarm was triggered 15 min later. Participants were instructed to only answer the questionnaires if they were at work.

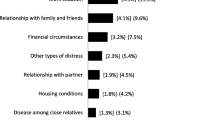

The workday set consisted of questions about stress experiences as well as further affective states described previously (Schilling et al., 2020). This paper will focus on the stress experiences only. Stress experiences were assessed with a single item: “How stressed do you feel at the moment?” The answer was given on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very). Validity of similar single items for the assessment of stress symptoms has been provided previously (Elo, Leppänen, & Jahkola, 2004). Due to the assumed day-level association of stress experiences at work with subsequent physical activity after work, stress experiences of one workday have been aggregated. In order to support validity of this parameter, we can provide correlations with further stress measures, which were assessed as part of the bigger project and are not of further interest for the present paper. The additional measures are (a) the evening assessment of overall perceived stress at work (EMA evening prompt), (b) the 16-item Effort–Reward Imbalance Questionnaire (Siegrist, 1996). Correlations with stress at work were r = 0.59 (p < 0.001) for the evening assessment of stress at work, and r = 0.47 (p < 0.001) for the Effort–Reward Imbalance ratio.

Physical activity.

Physical activity was assessed using ecgMove3 sensors (movisens GmbH). These sensors record three-dimensional acceleration (63 Hz), and barometric altitude (8 Hz) as raw data on internal memory. Evidence about validity and reliability to accurately capture physical activity has been provided previously (Härtel, Gnam, Löffler, & Bös, 2011). Participants wore the device on a textile dry electrode chest belt. Data were processed with the DataAnalyzer software (movisens GmbH). This software provides a report of activity classes, and nonwear time (Anastasopoulou, Stetter, & Hey, 2013; Anastasopoulou, Tansella, Stumpp, Shammas, & Hey, 2012; Härtel et al., 2011). The cut points have been set at 60-seconds epochs assuming an appropriate resolution to describe the activity behavior in adults (Trost, McIver, & Pate, 2005). Only participants with less than 30 min of recorded nonwear time for each segment of work or after-work physical activity were included. Physical activity scores (in minutes) were derived for MVPA at work, and MVPA after work (Anastasopoulou et al., 2013; Härtel et al., 2011).

Dispositional self-control.

Dispositional self-control was measured once via online questionnaire with a German short form of the Self-Control Scale (SCS; Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004). The instrument consists of 13 items (e.g., “I am good at resisting temptation.” or “I have a hard time breaking bad habits.”), which were answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The mean score was calculated to obtain an overall index, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of dispositional self-control. The validity and reliability of the SCS have been documented previously (Bertrams & Dickhäuser, 2009).

Cardiorespiratory fitness.

Cardiorespiratory fitness was assessed with the validated and internationally applied Åstrand Fitness Test (Nordgren et al., 2014). In a submaximal performance test on a bicycle ergometer (Ergofit Ergo Cycle 1500), maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) was estimated by standardized extrapolations of heart rates at certain resistances (Åstrand & Rodahl, 2003; Foss & Keteyian, 1998). Standardized instructions prior to the testing included the avoidance of any strenuous physical activity for 24 h, as well as heavy meals, and liquids other than water for 3 h. For the test, participants were equipped with a heart rate monitor (Polar Electro, Kempele, Finland). Standardized workloads were set for men (150 W) and women (100 W). This workload was adjusted to keep the heart rate in the range of 130–160 (bpm) for participants < 40 years, and 120–150 (bpm) for participants ≥ 40 years. Cycling cadence was set at 60 rotations per minute. At the end of each minute, heart rate was noted, and participants stated their perceived exertion on the Borg scale (Borg, 1998). Prior to the test, participants were instructed that perceived exertion should be between 11 and 16 points on the scale (below the maximum range; Borg, 1998). Standardized encouragements were used and participants were controlled for cancelation criteria (Ferguson, 2014). After 6 min, the test ended if the heart rate during the last 2 min did not vary by more than 5 beats per minute. Otherwise, participants were asked to proceed for another minute until this criterion was met. The mean heart rate of the final 2 min was compared against the final stage watts to achieve a gender adjusted VO2max (ml/kg/min).

Anthropometry.

Height was measured to the nearest 5 mm using a stationary stadiometer. Weight was assessed with a wireless body composition monitor (BC-500; Tanita Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Statistical analyses

While the data structure of stress experiences at work offers multiple measurements per individual, aggregated mean levels of this parameter were used in the present analyses. Herein, the analyses are consistent with the theoretical assumption that daily levels of stress experiences at work would negatively influence the level of physical activity after work. This approach aims for a simplified statistical model of a phenomena that is complex in structure. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all main study variables (Table 1). Furthermore, in order to summarize the data, to show the degree of relationship between the main study variables, and to substantiate the subsequent moderation analysis, bivariate correlations are provided (Table 2). Bivariate Pearson product–moment correlations were calculated between the continuous variables MVPA at work and after work (accelerometry), cardiorespiratory fitness, perceived stress at work, dispositional self-control, hours worked, and hours after work. To explore possible moderating effects of dispositional self-control on the relationship between stress at work and MVPA after work, we performed a 5-step hierarchical linear regression analysis (Table 3). Following the procedures proposed by Aiken and West (1991), the moderating effect of dispositional self-control was tested via the interaction term. Variables were entered in the regression equation in the following order: sociodemographic background and BMI (step 1), hours worked and hours after work (step 2), estimated VO2max and physical activity at work (step 3), stress at work and dispositional self-control (step 4), and the interaction term between stress at work and dispositional self-control (step 5). Stress at work and self-control were centered (z-standardized) before the interaction term was calculated. In the results section, we report the stepwise changes in R2, and the regression weights (including standardized Betas) for each predictor variable in the final model. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), and p-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Due to severe deviations from the normal distribution (West, Finch, & Curran, 1995), MVPA at work and MVPA after work were log-transformed before the regression analysis was calculated.

Results

Sample description

As reported above, the initial sample consisted of 201 police officers, of which 166 (82.6%) provided valid accelerometer data, 176 had valid real-life stress data (87.6%), and 190 answered the online questionnaire including sociodemographic variables and dispositional self-control (94.5%). For the present analyses, we used data from 153 individuals who had complete data across all study variables. This final sample had a mean age of 39.34 ± 10.37 years (range 22–62 years), consisted of 50 women (32.7%), and 66 participants (43.1%) worked in the shift schedule. Moreover, 11.8% (n = 18) had higher education (university or college), 30.7% (n = 37) had a high school degree, whereas 57.5% (n = 88) had basic vocational education and training.

Descriptive statistics for all main study variables are presented in Table 1. Mean time worked is below 8 h due to the proportion of shift workers who had a 7 h shift at the day of the data assessment. Participants answered 6.50 ± 1.39 prompts during the workday.

Bivariate correlations between study variables

Table 2 displays the bivariate correlations between the study variables. Time worked showed a small positive correlation with MVPA at work, whereas time after work was positively associated with MVPA after work. Stress at work was positively correlated with time worked. Higher dispositional self-control was negatively correlated with perceived stress at work. Moreover, higher VO2max was associated with lower BMI, whereas lower BMI was weakly, but significantly correlated with higher dispositional self-control and higher MVPA at work. MVPA at work was positively correlated with MVPA after work. No significant association was observed for stress at work and MVPA at/after work.

Main and interaction effects of stress at work, dispositional self-control on MVPA after work

As shown in Table 3, the hierarchical linear regression explained 14% variance in MVPA after work. In the final model, no significant association was found between MVPA after work, sociodemographic background and BMI (step 1). Although shift work, higher BMI, higher age, and more hours worked were related to decreased MVPA after work, none of these predictors reached the level of statistical significance. Against our expectation, neither stress at work, dispositional self-control nor the interaction between the latter two variables significantly explained variations in MVPA after work in the regression model.

Discussion

We investigated the effects of acute stress at work on MVPA after work in consideration of dispositional self-control as a moderating variable. We hypothesized that with increased experiences of stress at work, individuals with higher levels of dispositional self-control would be more likely to maintain their levels of MVPA after work. However, this assumption was not confirmed in the present sample of police officers. Thus, the level of stress at work did not significantly predict the level of MVPA after work, regardless of the level of dispositional self-control.

This finding is to some extent at odds with previous evidence. Sonnentag and Jelden (2009) showed that police officers’ situational constraints were in fact negatively related to self-regulatory resources and physical activity after work. However, role ambiguity and time pressure as different types of stressors did not show similar effects. Consequently, different stressors may antecede different effects on self-regulatory measures as well as health behaviors. These effects could be explained by different stress regulatory pathways in the brain (Maier, Makwana, & Hare, 2015). However, evidence regarding interaction effects of stress and dispositional self-control on subsequent physical activity is scarce. Some studies on the more general effects of psychosocial stress on subsequent physical activity indicate possible gender effects. A study with police officers by Ramey et al. (2014) presented evidence that the association of psychosocial stress at work and subsequent physical activity was not direct but moderated by gender. However, we did not find significant effects based on gender in the present sample. In a sample of college-aged women, Lutz, Stults-Kolehmainen, and Bartholomew (2010) showed that sports participation under stress was predicted by stages of change. During the examination period, participants in the maintenance stage exercised more, while other stages showed the opposite or no associations. The explanation presented by Lutz et al. (2010) was that consistent exercisers invested self-regulatory efforts in executing the health behavior over a long period of time. In turn, there would be less self-regulation involved in the later stages of change. Scholars generally agree that self-control constitutes a major source of self-regulation (Baumeister et al., 1994; Tangney et al., 2004). Consequently, self-control may determine the long-term formation of behavior, rather than short-term variations (de Ridder et al., 2012). Hence, self-control would be an important factor in the formation of automatization/habit (de Ridder et al., 2012), which, in turn, would make a behavior less prone to depletion of self-control resources (Hagger et al., 2016). This is in line with the above-mentioned study by Sonnentag and Jelden (2009) who assessed routines for off-job activities as a measure of automatization/habit. The authors showed that routines for off-job activities were positively related to leisure time sports activities. However, routines for off-job activities did not moderate the relationship between daily levels of stress at work and subsequent physical activity after work (Sonnentag & Jelden, 2009).

In summary, with the assumed effects of different levels of habituality of physical activity, the current findings are more consistent with previous research, which mainly focused on inactive individuals. Choi et al. (2010), for example, found effects of work stress on physical activity after work in a sample of 2019 workers (age range 32–69 years) where merely 15% of the participants were moderately to vigorously active. In the present sample, the percentage of participants who did not perform MVPA after work was only 5.2%. Of those who were moderately to vigorously active, 80.4% performed at least 30 min of MVPA per day. These activity levels include a certain possibility of habituality, which, as described above, may be less affected by daily stressful experiences. Our dataset does not allow interpretations of this mechanism due to the fact that levels of habituality of physical activity were not assessed. Nevertheless, in an occupation as policing, for many employees, physical activity and resulting fitness are necessary components to execute services safely (for the officers themselves and for coworkers). Therefore, exercise training is part of professional education, fitness tests are common practice, and sport facilities are easily accessible, which reflects a certain cultural integration of physical activity behavior (Waters & Ussery, 2007; Westmarland, 2017). While stress has been shown to influence a multitude of health behaviors (Park & Iacocca, 2014), dispositional self-control has been shown to be more important to some behaviors than others (de Ridder et al., 2012). Due to these circumstances and the additional relevance of shift work, other health behaviors (such as eating behavior) may be more prone to varying levels of psychosocial stress in police officers (Can & Hendy, 2014; Westmarland, 2017).

In this respect, we want to highlight the positive correlation between dispositional self-control and psychosocial stress in the present data. This result is in line with previous research on the direct association between dispositional self-control and psychosocial stress (Galla & Wood, 2015; Nielsen, Bauer, & Hofmann, 2020). The evidence base, however, is small and mainly relies on student samples; hence, the present study is one of the first investigations providing evidence in an occupational setting. Galla and Wood (2015) explained the effect of self-control on stress experiences with the dual-process model (Strack & Deutsch, 2004), in which automatic processes stand opposite costlier reflective processes. These automatic processes are thought to be efficient responses with little to no conscious awareness or intention involved. Reflective processes, on the other hand, are costlier higher-order processes that take more time to process and involve intention. Therefore, intention-oriented behavior is generally rooted in reflective processes and eventually becomes habitual over time. Following Galla and Wood (2015), self-control has to be exerted when reflective and automatic processes are in conflict. With lower resources available, for example, if psychosocial stress is high, automatic processes are more likely to determine thoughts, emotions, and behavior. In these situations, individuals with higher levels of dispositional self-control are more able to exert reflective processes and follow their long-term goals. The capacity to shift towards reflective processes has been termed thought control ability and was shown to be a strong predictor of psychological health and well-being (Luciano, Algarabel, Tomás, & Martínez, 2005). Taken together, while coping mechanisms may influence health behavior, self-control may alter stress appraisals in the first place. Hence, dispositional self-control may buffer the effects of psychosocial stress on health behaviors, by changing the stress experience/exposure (Nielsen et al., 2020). This, however, would cover the measurable effects of psychosocial stress experiences on health behaviors. This proposed mechanism is speculative at this point. Based on the data presented here, we can merely state that self-control seemed to alter stress experiences in police officers.

The strength of our study was that we examined our research question in a naturalistic setting with psychometric data being assessed in almost real-time. This novelty is an advantage over previous work because of its high external validity and a lowered recall bias. Furthermore, we controlled for fitness levels, which is an important factor in the relationship between affect and intensity of physical activity (Lutz et al., 2010). Despite these advantages, the findings of the present study have to be interpreted with caution due to several limitations. These limitations include the use of a convenience sampling method, a relatively high level of physical activity in the sample, as well as an uneven gender distribution, which may be representative of a general police force, but not a general population. Based on the increased standard error related to the interaction term in statistical analyses, the present sample size may have been a limiting factor in detecting significant main and interaction effects. Furthermore, while the applied methodology offers realistic insight in the acute stress perception of police officers, the assessment did not take place in a controlled setting. Therefore, it could be argued that the stress experiences at work may not have been sufficient to show effects on health behavior. However, theory as well as empirical evidence unanimously support the assumption that police officers encounter a multitude of occupational stressors and that resulting perceived stress is accordingly high (Arial, Gonik, Wild, & Danuser, 2010; Gerber, Hartmann, Brand, Holsboer-Trachsler, & Pühse, 2010; Simons & Barone, 1994; Violanti et al., 2017). In order to approach this issue in future research, assessment over longer periods of time could be considered in order to increase the chances of variability in stress experiences. The assessment of daily stress over several weeks would lower participant’s ability to anticipate stress levels. This approach would further reveal whether physical activity levels differ on days with low, moderate or high stress levels and further facilitate within-person analysis.

Conclusion

The present data did not support the assumption that stress at work influences physical activity levels after work in police officers. However, based on the limited empirical evidence available, no final conclusions can be drawn regarding the generalizability of these results. This study offers new insights based on state-of-the art ecological momentary assessment of feelings of stress in real life. When feasible, similar research endeavors should consider longer assessment periods for a greater variety in daily stress levels.

References

Anastasopoulou, P., Tansella, M., Stumpp, J., Shammas, L., & Hey, S. (2012). Classification of human physical activity and energy expenditure estimation by accelerometry and barometry. Conference proceedings: … Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Conference, 2012, 6451–6454. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC.2012.6347471.

Anastasopoulou, P., Stetter, B., & Hey, S. (2013). Validierung der Bewegungsklassifikation des move II Aktivitätssensonsors im Alltag. Paper presented at the Sportwissenschaftlicher Hochschultag der Deutschen Vereinigung für Sportwissenschaft. Konstanz, Germany.

Åstrand, P.-O., & Rodahl, K. (2003). Textbook of work physiology: Physiological bases of exercise. Champaign: Human Kinetics.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

American Psychological Association (2017). Stress in America: The state of our nation (Nov. 1, 2017). https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2017/11/lowest-point. Accessed 20.04.2022.

Arial, M., Gonik, V., Wild, P., & Danuser, B. (2010). Association of work related chronic stressors and psychiatric symptoms in a Swiss sample of police officers; a cross sectional questionnaire study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health, 83(3), 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-009-0500-z.

Baumeister, R., Heatherton, T., & Tice, D. (1994). Losing control: How and why people fail at self-regulation. San Diego: Academic Press.

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x.

Bertrams, A., & Dickhäuser, O. (2009). Messung dispositioneller Selbstkontroll-Kapazität. Diagnostica, 55(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924.55.1.2.

Borg, G. (1998). Borg’s perceived exertion and pain scales. Champaign: Human Kinetics.

Brown, J. M., & Campbell, E. A. (1990). Sources of occupational stress in the police. Work & Stress, 4(4), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678379008256993.

Buckingham, S. A., Morrissey, K., Williams, A. J., Price, L., & Harrison, J. (2020). The physical activity wearables in the police force (PAW-force) study: Acceptability and impact. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1645. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09776-1.

Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., et al. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(24), 1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955.

Can, S., & Hendy, H. (2014). Behavioral variables associated with obesity in police officers. Industrial Health, 52, 240–247.

Chandola, T., Britton, A., Brunner, E., Hemingway, H., Malik, M., Kumari, M., et al. (2008). Work stress and coronary heart disease: What are the mechanisms? European Heart Journal, 29(5), 640–648. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehm584.

Choi, B., Schnall, P. L., Yang, H., Dobson, M., Landsbergis, P., & Israel, L. (2010). Psychosocial working conditions and active leisure-time physical activity in middle-aged us workers. Int J Occup Med Environ Health, 23(3), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10001-010-0029-0.

Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., & Miller, G. E. (2007). Psychological stress and disease. JAMA, 298(14), 1685–1687. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.14.1685.

Crescioni, A. W., Ehrlinger, J., Alquist, J. L., Conlon, K. E., Baumeister, R. F., Schatschneider, C., & Dutton, G. R. (2011). High trait self-control predicts positive health behaviors and success in weight loss. J Health Psychol, 16(5), 750–759. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105310390247.

Ekelund, U., Dalene, K. E., Tarp, J., & Lee, I.-M. (2020). Physical activity and mortality: what is the dose response and how big is the effect? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(19), 1125–1126. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101765.

Elfering, A., Grebner, S., Semmer, N., Kaiser-Freiburghaus, D., Ponte, S., & Witschi, I. (2005). Chronic job Stressors and job control: Effects on event-related coping success and well-being. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X40088.

Elo, A.-L., Leppänen, A., & Jahkola, A. (2004). Validity of a single-item measure of stress symptoms. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 29, 444–451. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.752.

Englert, C. (2016). The strength model of self-control in sport and exercise psychology. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00314.

Faries, M. D. (2016). Why we don’t “Just do it”: understanding the intention-behavior gap in lifestyle medicine. American journal of lifestyle medicine, 10(5), 322–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827616638017.

Ferguson, B. (2014). ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 9th Ed. 2014. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 58(3), 328–328.

Foss, M. L. K., & Keteyian, S. J. (1998). Fox’s physiological basis for exercise and sport (6th edn.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Fransson, E. I., Heikkila, K., Nyberg, S. T., Zins, M., Westerlund, H., Westerholm, P., et al. (2012). Job strain as a risk factor for leisure-time physical inactivity: an individual-participant meta-analysis of up to 170,000 men and women: the IPD-Work Consortium. Am J Epidemiol, 176(12), 1078–1089. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws336.

Fredrickson, B., & Kahneman, D. (1993). Duration neglect in retrospective evaluations of affective episodes. Journal of personality and social psychology, 65(1), 45–55.

Galla, B. M., & Wood, J. J. (2015). Trait self-control predicts adolescents’ exposure and reactivity to daily stressful events. Journal of Personality, 83(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12083.

Gerber, M., & Pühse, U. (2009). Review article: do exercise and fitness protect against stress-induced health complaints? A review of the literature. Scand J Public Health, 37(8), 801–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494809350522.

Gerber, M., & Schilling, R. (2018). Stress als Risikofaktor für körperliche und psychische Gesundheitsbeeinträchtigungen. In R. Fuchs & M. Gerber (Eds.), Handbuch Stressregulation und Sport (pp. 93–122). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Gerber, M., Börjesson, M., Ljung, T., Lindwall, M., & Jonsdottir, I. H. (2016). Fitness moderates the relationship between stress and cardiovascular risk factors. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 48(11), 2075–2081. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000001005.

Gerber, M., Fuchs, R., & Pühse, U. (2013). Selbstkontrollstrategien bei hohem wahrgenommenem Stress und hohen Bewegungsbarrieren: Bedeutung für die Erklärung sportlicher Aktivität bei Polizeiangestellten. Zeitschrift für Sportpsychologie, 20, 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1026/1612-5010/a000098.

Gerber, M., Hartmann, T., Brand, S., Holsboer-Trachsler, E., & Pühse, U. (2010). The relationship between shift work, perceived stress, sleep and health in Swiss police officers. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(6), 1167–1175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.09.005.

Gerber, M., Lindwall, M., Brand, S., Lang, C., Elliot, C., & Pühse, U. (2015). Longitudinal relationships between perceived stress, exercise self-regulation and exercise involvement among physically active adolescents. J Sports Sci, 33(4), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.946072.

Gerber, M., Schilling, R., Colledge, F., Ludyga, S., Pühse, U., & Brand, S. (2019). More than a simple pastime? The potential of physical activity to moderate the relationship between occupational stress and burnout symptoms. International Journal of Stress Management. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000129.

Hagger, M. S., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., Alberts, H., Anggono, C. O., Batailler, C., Birt, A. R., et al. (2016). A multilab preregistered replication of the ego-depletion effect. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(4), 546–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616652873.

Hagger, M. S., Wood, C. W., Stiff, C., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2010). Self-regulation and self-control in exercise: The strength-energy model. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 3(1), 62–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/17509840903322815.

Härtel, S., Gnam, J.-P., Löffler, S., & Bös, K. (2011). Estimation of energy expenditure using accelerometers and activity-based energy models—Validation of a new device. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity, 8(2), 109–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11556-010-0074-5.

Huang, B. H., Duncan, M. J., Cistulli, P. A., Nassar, N., Hamer, M., & Stamatakis, E. (2021a). Sleep and physical activity in relation to all-cause, cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality risk. British Journal of Sports Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2021-104046.

Huang, B. H., Hamer, M., Chastin, S., Pearson, N., Koster, A., & Stamatakis, E. (2021b). Cross-sectional associations of device-measured sedentary behaviour and physical activity with cardio-metabolic health in the 1970 British Cohort Study. Diabetic Medicine, 38(2), e14392. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14392.

Isoard-Gautheur, S., Ginoux, C., Gerber, M., & Sarrazin, P. (2019). The stress-burnout relationship: Examining the moderating effect of physical activity and intrinsic motivation for off-job physical activity. Workplace Health & Safety, 67(7), 350–360.

Kasten, N., & Fuchs, R. (2018). Methodische Aspekte der Stressforschung. In R. Fuchs & M. Gerber (Eds.), Handbuch Stressregulation und Sport (pp. 1–30). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Kinnunen, M. I., Suihko, J., Hankonen, N., Absetz, P., & Jallinoja, P. (2012). Self-control is associated with physical activity and fitness among young males. Behav Med, 38(3), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2012.693975.

Kivimäki, M., Nyberg, S. T., Fransson, E. I., Heikkilä, K., Alfredsson, L., & Casini, A. (2013). Associations of job strain and lifestyle risk factors with risk of coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis of individual participant data. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 185(9), 763–769. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.121735.

Klaperski, S. (2018). Exercise, stress and health: The stress-buffering effect of exercise. In R. Fuchs & M. Gerber (Eds.), Handbuch Stressregulation und Sport (pp. 227–249). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Kouvonen, A., Vahtera, J., Oksanen, T., Pentti, J., Väänänen, A. K., Heponiemi, T., et al. (2013). Chronic workplace stress and insufficient physical activity: a cohort study. Occup Environ Med, 70(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2012-100808.

Luciano, J. V., Algarabel, S., Tomás, J. M., & Martínez, J. L. (2005). Development and validation of the thought control ability questionnaire. Press release

Lutz, R. S., Stults-Kolehmainen, M. A., & Bartholomew, J. B. (2010). Exercise caution when stressed: Stages of change and the stress-exercise participation relationship. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(6), 560–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.06.005.

Maier, S. U., Makwana, A. B., & Hare, T. A. (2015). Acute stress impairs self-control in goal-directed choice by altering multiple functional connections within the brain’s decision circuits. Neuron, 87(3), 621–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.005.

Martin Ginis, K. A., & Bray, S. R. (2010). Application of the limited strength model of self-regulation to understanding exercise effort, planning and adherence. Psychology & Health, 25(10), 1147–1160. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903111696.

McCarty, W. P., Aldirawi, H., Dewald, S., & Palacios, M. (2019). Burnout in blue: An analysis of the extent and primary predictors of burnout among law enforcement officers in the United States. Police Quarterly, 22(3), 278–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611119828038.

McCreary, D. R., & Thompson, M. M. (2006). Development of two reliable and valid measures of stressors in policing: The operational and organizational police stress questionnaires. International Journal of Stress Management, 13(4), 494.

Mora, S., Cook, N., Buring, J. E., Ridker, P. M., & Lee, I. M. (2007). Physical activity and reduced risk of cardiovascular events: potential mediating mechanisms. Circulation, 116(19), 2110–2118. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.107.729939.

Nielsen, K. S., Bauer, J. M., & Hofmann, W. (2020). Examining the relationship between trait self-control and stress: Evidence on generalizability and outcome variability. Journal of Research in Personality, 84, 103901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.103901.

Nordgren, B., Fridén, C., Jansson, E., Österlund, T., Grooten, W. J., Opava, C. H., & Rickenlund, A. (2014). Criterion validation of two submaximal aerobic fitness tests, the self-monitoring Fox-walk test and the Åstrand cycle test in people with rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 15, 305. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-305.

Oaten, M., & Cheng, K. (2006). Improved self-control: The benefits of a regular program of academic study. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 28, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp2801_1.

Park, C. L., & Iacocca, M. O. (2014). A stress and coping perspective on health behaviors: theoretical and methodological considerations. Anxiety Stress Coping, 27(2), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2013.860969.

Ramey, S. L., Perkhounkova, Y., Moon, M., Tseng, H. C., Wilson, A., Hein, M., et al. (2014). Physical activity in police beyond self-report. J Occup Environ Med, 56(3), 338–343. https://doi.org/10.1097/jom.0000000000000108.

Reichert, M., Giurgiu, M., Koch, E., Wieland, L., Lautenbach, S., Neubauer, A., et al. (2020). Ambulatory assessment for physical activity research: State oft he science, best practices and future directions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 50, 101742.

Rhodes, R. E., & Courneya, K. S. (2003). Investigating multiple components of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived control: an examination of the theory of planned behaviour in the exercise domain. Br J Soc Psychol, 42(Pt 1), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466603763276162.

de Ridder, D. T., Lensvelt-Mulders, G., Finkenauer, C., Stok, F. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2012). Taking stock of self-control: a meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Pers Soc Psychol Rev, 16(1), 76–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311418749.

Sax, L. J. (1997). Health trends among college freshmen. Journal of American College Health, 45(6), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.1997.9936895.

Schilling, R., Colledge, F., Ludyga, S., Puhse, U., Brand, S., & Gerber, M. (2019). Does cardiorespiratory fitness moderate the association between occupational stress, cardiovascular risk, and mental health in police officers? Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132349.

Schilling, R., Herrmann, C., Ludyga, S., Colledge, F., Brand, S., Pühse, U., & Gerber, M. (2020). Does cardiorespiratory fitness buffer stress reactivity and stress recovery in police officers? A real-life study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00594.

Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high effort—Low reward conditions at work. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 1, 27–43.

Simons, Y., & Barone, D. F. (1994). The relationship of work stressors and emotional support to strain in police officers. International Journal of Stress Management, 1(3), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01857989.

Slopen, N., Kontos, E. Z., Ryff, C. D., Ayanian, J. Z., Albert, M. A., & Williams, D. R. (2013). Psychosocial stress and cigarette smoking persistence, cessation, and relapse over 9–10 years: a prospective study of middle-aged adults in the United States. Cancer Causes Control, 24(10), 1849–1863. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-013-0262-5.

Sonnentag, S., & Jelden, S. (2009). Job stressors and the pursuit of sport activities: A day-level perspective. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(2), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014953.

Stone, A. A., & Shiffman, S. (1994). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavorial medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 16(3), 199–202. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/16.3.199.

Strack, F., & Deutsch, R. (2004). Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Rev, 8(3), 220–247. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_1.

Stults-Kolehmainen, M., & Sinha, R. (2013). The effects of stress on physical activity and exercise. Sports Medicine, 44(1), 81–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0090-5.

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers, 72(2), 271–324.

Tomitaka, S., Kawasaki, Y., Ide, K., Akutagawa, M., Ono, Y., & Furukawa, T. A. (2019). Distribution of psychological distress is stable in recent decades and follows an exponential pattern in the US population. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 11982. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47322-1.

Trost, S. G., McIver, K. L., & Pate, R. R. (2005). Conducting Accelerometer-Based Activity Assessments in Field-Based Research. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 37(11).

Violanti, J. M., Charles, L. E., McCanlies, E., Hartley, T. A., Baughman, P., & Andrew, M. E. (2017). Police stressors and health: A state-of-the-art review. Policing, 40(4), 642–656. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-06-2016-0097.

Waters, J., & Ussery, W. (2007). Police stress: History, contributing factors, symptoms, and interventions. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 30, 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510710753199.

West, S. G., Finch, J. F., & Curran, P. J. (1995). Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling. Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 56–75). Thousand Oakes: SAGE.

Westmarland, L. (2017). Putting their bodies on the line: police culture and gendered physicality. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 11(3), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pax019.

Wills, T. A., Isasi, C. R., Mendoza, D., & Ainette, M. G. (2007). Self-control constructs related to measures of dietary intake and physical activity in adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 41(6), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.06.013.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Basel

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

R. Schilling, R. Cody, S. Ludyga, S. Brand,O. Faude, U. Pühse and M. Gerber declare that they have no competing interests.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies mentioned were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

Supplementary Information

12662_2022_810_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Figure 1: Scatterplot illustrating the relationship between stress at work (independent variable) and MVPA after work (dependent variable) for the entire sample (n = 153)

Figure 2: Scatterplot illustrating the relationship between stress at work (independent variable) and MVPA after work (dependent variable) for men (103) and women (n = 50)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schilling, R., Cody, R., Ludyga, S. et al. Does dispositional self-control moderate the association between stress at work and physical activity after work? A real-life study with police officers. Ger J Exerc Sport Res 52, 290–299 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-022-00810-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-022-00810-5