Abstract

Purpose

Although many patients agree to participate in research studies, many decline. The decision of whether or not to participate is especially complex in pregnant individuals as they may be concerned about both themselves and the fetus. We sought to understand patient reasoning for and demographic associations with participation in a trial surrounding the utility of epidural preservative-free morphine after successful vaginal delivery.

Methods

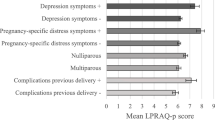

We conducted a survey-based study in which parturients were approached within 36 hr after delivery to complete a survey assessing reasons for why they participated or not in the original trial. The survey also included self-reported demographics. Survey responses were categorized as follows: active participation, passive participation, ambivalence, aversion, miscommunication, clinical difficulty, unwilling to receive placebo, and screening failures.

Results

The survey response rate was 47%. Having a bachelor’s degree or higher was associated with participating in the study (odds ratio [OR], 1.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07 to 3.64; P = 0.03). Race and ethnicity were not predictive of participation. Participants who self-identified as Black were more likely to select reasons of aversion for why they did not participate in the trial (OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.00 to 6.75; P = 0.05). Seventy-three percent of participants who self-identified as Black and declined to participate selected aversion, compared with 31% of those who self-identified as non-Black. Additionally, 71% of participants who self-identified as Hispanic and declined to participate selected aversion, compared with 32% of those who self-identified as non-Hispanic.

Conclusions

These findings can help identify areas for improvement of participation of pregnant individuals in research studies. Demographic associations may influence participation and reasons for participation.

Résumé

Objectif

Bien que bon nombre de patient·es acceptent de participer à des études de recherche, beaucoup déclinent. La décision de participer ou non est particulièrement complexe chez les personnes enceintes, car elles peuvent être inquiètes pour elles-mêmes et pour le fœtus. Nous avons cherché à comprendre le raisonnement des patient·es et les associations démographiques concernant la participation à une étude portant sur l’utilité de la morphine péridurale sans agent de conservation après un accouchement vaginal réussi.

Méthode

Nous avons mené une étude basée sur des questionnaires dans laquelle les personnes parturientes ont été approchées dans les 36 heures suivant l’accouchement afin de compléter un questionnaire évaluant les raisons pour lesquelles elles avaient participé ou non à l’étude initiale. Le questionnaire comprenait également des données démographiques autodéclarées. Les réponses au questionnaire ont été classées comme suit : participation active, participation passive, ambivalence, aversion, mauvaise communication, difficulté clinique, refus de recevoir un placebo et échecs au dépistage.

Résultats

Le taux de réponse était de 47 %. Le fait d’avoir un baccalauréat ou plus était associé à la participation à l’étude (rapport de cotes [RC], 1,97; intervalle de confiance [IC] à 95 %, 1,07 à 3,64; P = 0,03). La race et l’origine ethnique n’étaient pas prédictives de la participation. Les participant·es qui se sont identifié·es comme Noir·es étaient plus susceptibles de choisir des raisons d’aversion pour expliquer leur non-participation à l’étude (RC, 2,6; IC 95 %, 1,00 à 6,75; P = 0,05). Soixante-treize pour cent des participant·es qui se sont identifié·es comme Noir·es et ont refusé de participer ont choisi l’aversion, comparativement à 31 % des personnes qui se sont identifié·es comme non Noir·es. De plus, 71 % des participant·es qui se sont identifié·es comme d’origine hispanique et ont refusé de participer ont choisi l’aversion, comparativement à 32 % des personnes qui se sont identifié·es comme non Hispaniques.

Conclusion

Ces résultats peuvent aider à identifier les domaines dans lesquels la participation des personnes enceintes aux études de recherche peut être améliorée. Les associations démographiques peuvent influencer la participation et les raisons de la participation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Campbell MK, Snowdon C, Francis D, et al. Recruitment to randomised trials: strategies for trial enrollment and participation study. The STEPS study. Health Technol Assess 2007; 11: ix–105. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta11480

Charlson ME, Horwitz RI. Applying results of randomised trials to clinical practice: impact of losses before randomisation. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984; 289: 1281–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.289.6454.1281

Merkatz RB, Temple R, Subel S, Feiden K, Kessler DA. Women in clinical trials of new drugs. A change in Food and Drug Administration policy. The Working Group on Women in Clinical Trials. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 292–6. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199307223290429

Pinnow E, Sharma P, Parekh A, Gevorkian N, Uhl K. Increasing participation of women in early phase clinical trials approved by the FDA. Womens Health Issues 2009; 19: 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2008.09.009

Andrade SE, Gurwitz JH, Davis RL, et al. Prescription drug use in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 191: 398–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.04.025

Lyerly AD, Little MO, Faden R. The second wave: toward responsible inclusion of pregnant women in research. Int J Fem Approaches Bioeth 2008; 1: 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1353/ijf.0.0047

Task Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women. Report implementation plan. 2020. Available from URL: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/inline-files/PRGLAC_Implement_Plan_083120.pdf (accessed July 2023).

Baker L, Lavender T, Tincello D. Factors that influence women's decisions about whether to participate in research: an exploratory study. Birth 2005; 32: 60–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00346.x

Kenyon S, Dixon-Woods M, Jackson CJ, Windridge K, Pitchforth E. Participating in a trial in a critical situation: a qualitative study in pregnancy. Qual Saf Health Care 2006; 15: 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2005.015636

Lyerly AD, Namey EE, Gray B, Swamy G, Faden RR. Women’s views about participating in research while pregnant. IRB 2012; 34: 1–8.

Meshaka R, Jeffares S, Sadrudin F, Huisman N, Saravanan P. Why do pregnant women participate in research? A patient participation investigation using Q-Methodology. Health Expect 2017; 20: 188–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12446

Rodger MA, Makropoulos D, Walker M, Keely E, Karovitch A, Wells PS. Participation of pregnant women in clinical trials: will they participate and why? Am J Perinatol 2003; 20: 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2003-38318

Smyth RM, Jacoby A, Elbourne D. Deciding to join a perinatal randomised controlled trial: experiences and views of pregnant women enroled in the Magpie Trial. Midwifery 2012; 28: E478–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2011.08.006

van der Zande IS, van der Graaf R, Oudijk MA, van Vliet-Lachotzki EH, van Delden JJ. A qualitative study on stakeholders’ views on the participation of pregnant women in the APOSTEL VI study: a low-risk obstetrical RCT. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019; 19: 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2209-7

Mohanna K, Tunna K. Withholding consent to participate in clinical trials: decisions of pregnant women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1999; 106: 892–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08426.x

Rengerink KO, Logtenberg S, Hooft L, Bossuyt PM, Mol BW. Pregnant womens’ concerns when invited to a randomized trial: a qualitative case control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015; 15: 207. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0641-x

Jansen T, Rademakers J, Waverijn G, Verheij R, Osborne R, Heijmans M. The role of health literacy in explaining the association between educational attainment and the use of out-of-hours primary care services in chronically ill people: a survey study. BMC Health Serv Res 2018; 18: 394. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3197-4

Hayes-Ryan D, Meaney S, Nolan C, O’Donoghue K. An exploration of women’s experience of taking part in a randomized controlled trial of a diagnostic test during pregnancy: a qualitative study. Health Expect 2020; 23: 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12969

Sutton EF, Cain LE, Vallo PM, Redman LM. Strategies for successful recruitment of pregnant patients into clinical trials. Obstet Gynecol 2017; 129: 554–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001900

Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Kuklina EV, Callaghan WM. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity: a multistate analysis, 2008–2010. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014; 210: e431–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2013.11.039

Tooher RL, Middleton PF, Crowther CA. A thematic analysis of factors influencing recruitment to maternal and perinatal trials. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2008; 8: 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-8-36

Robertson K, Reimold K, Moormann AM, Binder R, Matteson KA, Leftwich HK. Investigating demographic differences in patients' decisions to consent to COVID-19 research. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2023; 36: 2148097. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2022.2148097

Gamble VN. A legacy of distrust: African Americans and medical research. Am J Prev Med 1993; 9: 35–8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy-related deaths among Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native women—United States, 1991–1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001; 50: 361–4.

Allison K, Patel D, Kaur R. Assessing multiple factors affecting minority participation in clinical trials: development of the clinical trials participation barriers survey. Cureus 2022; 14: e24424. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.24424

The City of New York. New York City government poverty measure 2019: an annual report from the Office of the Mayor. 2021. Available from URL: https://www.nyc.gov/assets/opportunity/pdf/21_poverty_measure_report.pdf (accessed July 2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Talia A. Scott contributed to data curation, formal analysis, and writing (original draft). Cynthia R. Mercedes contributed to investigation, project administration, data curation, and writing (review and editing). Hung-Mo Lin contributed to formal analysis and writing (review and editing). Daniel Katz contributed to conceptualization, supervision, and writing (review and editing).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

None.

Funding statement

None.

Prior conference presentations

These data were presented at the 2023 Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology Annual Meeting in a Research & Case-Report Session (3–7 May, New Orleans, LA, USA).

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Ronald B. George, Associate Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Scott, T.A., Mercedes, C.R., Lin, HM. et al. Motivations and demographic differences in pregnant individuals in the decision to participate in research. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 71, 87–94 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02635-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02635-8