Abstract

The Chinese government has been actively recruiting foreign-trained Chinese scholars to return to China since the Chinese brain drain began. Japan is among the most popular destinations for Chinese scholars seeking to receive doctoral training. This study explores the factors contributing to the stratification of Japanese-trained Chinese PhDs’ academic career attainments using the Mertonian norm of universalism. The results indicate that the norm of universalism can partly explain the stratification of Japanese-trained Chinese PhDs. The reason for this is that their higher pre-graduation productivity enhances the chance that Japanese-trained Chinese PhDs have of obtaining an academic position at a top university in China. In addition to pre-graduation academic productivity, other factors, including the prestige of the university attended, the duration of the academic sojourn in Japan, and the ethnicity of the supervisor influence employment outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Academic mobility in the sense of a crossing of territorial borders is rooted at the very beginnings of the university in the Middle Ages, when students traveled to universities outside of their homelands for professional purposes (Avveduto, 2010; Kim, 2009). PhD students’ transnational mobility is among the most essential characteristics of modern doctoral education and was first institutionalized in the nineteenth century (Shen et al., 2016). In the present day, globalization taking place in all sectors of society has made transnational academic mobility highly systematic and frequent, profoundly influencing doctoral education (Kim, 2017; Kyvik et al., 1999; Nerad, 2010). Transnational mobility is likely to help develop globally aware, linked, and competitive doctoral students in their research and careers (Knight & Madden, 2010). Several studies have examined the positive influence of transnational mobility on doctoral students’ academic productivity (Aksnes et al., 2013; Shen & Jiang, 2021; Shen et al., 2017), international co-authorships (Jiang & Shen, 2019; Melkers & Kiopa, 2010; Meng, 2020), and academic career prospects (Kim, 2016).

Doctoral education in developed countries is attractive to students from developing countries, as it is commonly accepted that transnational mobility tends to enhance the quality of doctoral training and improve the academic careers of early stage scholars (Shen et al., 2017). Chinese scholars are no exception to this. Beginning with the reform and opening up in 1978, the Chinese government has been dispatching students to study abroad on an official basis. Because the college-entrance examinations were not restored until 1977, only a few students were qualified at first to study for overseas graduate degrees. Thus, approximately 1000 graduates with bachelor’s degrees first took the entrance examinations in 1977 and 1978 and were selected in 1981 and 1982 for doctoral study in Europe, North America, and Japan (Hayhoe, 1984). From that point on, the Chinese government has continuously increased its investment in the transnational mobility of its PhD students and scholars; for instance, in 1996, the Ministry of Education established the China Scholarship Council (CSC), which provides sustainable financial and policy support to promoting Chinese students’ and scholars’ transnational academic mobility (Liu et al., 2021). Thanks to the government’s endeavors, China is the world’s largest exporter of PhD students (Shen et al., 2016).

However, it has also realized that the rate of return of overseas students and scholars is significantly lower than expected, leading to a brain drain in the 1990s (Cao, 2008). The Chinese government has issued several preferential policies for overseas Chinese scholars, including the Hundred Talent Program, the Changjiang Scholar Program, and the Thousand Talent Program, to recruit the best and brightest to return home for the improvement of national scientific and technological capacity (Yang, 2020; Zweig, 2006). Chinese scholars with foreign PhD degrees have received particular attention from the government, as they are expected to help enhance China’s national scientific research capacity and link it more closely to the international scientific community (Cao et al., 2020; Li et al., 2018; Shen & Jiang, 2021; Shen et al., 2016).

Against this policy background, foreign-trained Chinese PhDs have received increasing attention from academia. Several studies have discussed the advantages and disadvantages developed by foreign-trained PhDs relative to their domestic counterparts. Transnational mobility is considered a symbol of strong competitiveness (Lu & Zhang, 2015; Zweig & Wang, 2013). However, returning Chinese scholars may suffer from slow advancement in their academic careers because of their lack of domestic connections, due to their absence from domestic academia (Li & Tang, 2019; Lu & McInerney, 2016). Numerous studies have paid exclusive attention to transnationally mobile Chinese PhDs and the factors that contribute to their stratification in terms of academic socialization (Li & Collins, 2014; Wu, 2017; Zheng, 2019), academic employment (Jiang et al., 2020), academic productivity (Jonkers & Tijssen, 2008; Shen & Jiang, 2021), and collaboration in international research (Horta et al., 2020; Jiang & Shen, 2019; Jonkers & Tijssen, 2008).

This study is concerned with the stratification of Japanese-trained Chinese PhDs in terms of their academic employment outcomes and productivity. English-speaking countries, in particular the United States (US), are the predominant destinations for Chinese students intending to study for their PhDs. However, Japan should not be ignored, as it is among the most important host countries in East Asia. Studying in Japan saw an upsurge in the Qing Dynasty, as China realized that its students should learn from Japan’s experience and modernized knowledge production. For this reason, the Qing government commenced sending students to Japan in 1896, and the annual number of its students dispatched to Japan dramatically increased, from 13 in 1896 to approximately 8000 in 1906. Today, Japan remains among the most popular host countries for Chinese students, including those pursuing doctoral degrees. From 2008 to 2014, the CSC funded a total of 41,909 Chinese graduate students in their pursuit of either PhDs abroad or 1 to 2 years of experience overseas. Japan was the sixth most popular destination country, accepting 2374 students, following the US (17,455), Germany (3998), the United Kingdom (UK) (3884), Canada (2856), and Australia (2701) (Shen et al., 2017). Japan is also a popular destination among elite Chinese scholars and entrepreneurs. According to Zweig and Wang (2013), Japan is the fourth most popular country or region for Thousand Talents recipients to go to acquire their PhDs, after the US, Europe (including the UK), and mainland China.

Several studies have examined the impact of experiences of academic mobility of Chinese scholars in Japan (Jonkers & Tijssen, 2008; Li et al., 2018; Meng, 2020). However, these studies predominantly focus on Chinese scientists who have established academic careers or those affiliated with elite higher-education or research institutes in China and overlook early career scientists and those employed by nonelite universities. This study adopts a highly comprehensive approach, involving a wide sample of Chinese doctoral students who received funding from the CSC for their studies in Japan. The study addresses the factors that contribute to the stratification of academic career achievements among Chinese PhDs who were trained in Japan.

Literature review

The norm of universalism

This study conducted a quantitative analysis of a sample of Japanese-trained Chinese PhDs, using Robert Merton’s (1973) norm of universalism. Science, as a social institution, has its own ethos including the four central norms of universalism, communism, disinterestedness, and organized skepticism. The norm of universalism includes two related principles. The first is the stricture to assess scientific claims objectively. No personal or social characteristics, including race, gender, or class, is relevant to the judgment of claims of truth or scientific discovery. The second is that scientists should be fairly rewarded based on their original contributions to scientific knowledge.

In the reward system of the scientific community, recognition and esteem accrue to scientists who most extend the stock of certified knowledge in their roles (Merton, 1973). As in other social institutions, reward allocation is unequal among members. However, many draw on the Mertonian tradition, empirically verifying whether rewards in academia are allocated in accordance with the norm of universalism (e.g., Allison & Long, 1987, 1990; Cole & Cole, 1967; Crane, 1965; Long, 1978; Long et al., 1979; Zuckerman, 1967).

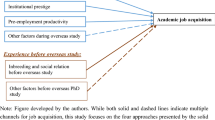

This study explores the extent to which the inequality of academic attainments among Japanese-trained Chinese PhDs can be explained using the norm of universalism. Figure 1 presents the analytic framework for this study. Four sets of factors are the foci of the analysis, namely, pre-graduation productivity, organizational, mobility, and supervisor factors.

Pre-graduation productivity

Several studies have explored the influence of pre-graduation productivity on individual scientists’ academic careers. Early studies in the sociology of science reported mixed findings on the effects of pre-graduation productivity on later academic productivity and academic positions (e.g., Baldi, 1995; Long, 1978; Long et al., 1979). Recent studies have shown that those who published during the period of their PhD study are more likely to have higher academic output after their PhD study (Horta & Santos, 2016; Pinheiro et al., 2014). Jiang et al. (2020) found that for returnee Chinese PhDs, pre-graduation productivity is an effective predictor for later academic employment outcomes, which is consistent with the universalism norm in academia. The reason for this is the beliefs that scientific careers should be open to talent, and that “recognition and esteem accrue to those who have best fulfilled their roles, to those who have made original contributions to scientific knowledge” (Merton, 1957). This study focuses on Chinese PhDs who previously studied in Japan. This study also explores whether the advantages accumulated before graduation by this group in the form of academic productivity contributed to their later success in their academic careers by testing the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

Japanese-trained Chinese PhDs with higher pre-graduation academic productivity tend to have more successful academic careers than those without.

Organizational factors

Extensive studies in the sociology of science emphasized organizational factors; among them is the prestige of a doctoral institution (e.g., Allison & Long, 1987, 1990; Burris, 2004; Cole & Cole, 1967; Headworth & Freese, 2016; Hurlbert & Rosenfeld, 1992; Long, 1978; Long et al., 1979). The origins of a doctorate have been verified as directly or indirectly affecting PhDs’ job placement in the forms of selection (Allison & Long, 1990), departmental (Allison & Long, 1990), and prestige (Headworth & Freese, 2016) effects, along with social capital (Burris, 2004).

In an investigation of transnationally mobile PhDs, Horta et al. (2020) found that for temporarily visiting Chinese PhD students, the prestige of the host university positively influenced the probability and intensity of later international academic collaboration. The experience of doctoral study at an elite university outside of the mainland likely helps PhDs integrate into international academic networks. However, Jiang et al. (2020) and Shen and Jiang (2021) found that the prestige of the host university has no significant impact on the academic employment of returning Chinese PhDs. Due to the mixed conclusions concerning the impact of doctoral origins on the academic performance and job acquisition of internationally trained Chinese PhDs, this study was designed to test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2.1:

Japanese-trained Chinese PhDs who have studied at top universities in Japan tend to have more successful academic careers than those who have not.

In addition to one’s doctorate education, research has also shown that obtaining a bachelor’s degree from a selective undergraduate institution also predicts subsequent academic career success. The reason for this that the experience gained at a prestigious university in undergraduate study can compensate for potential disadvantages associated acquiring a doctorate from a less prestigious institution (Baldi, 1995; Burris, 2004; Long et al., 1979).

For Chinese PhD returnees, an undergraduate degree from a top university has only marginal significance regarding whether the individual is later employed by an elite university in China (Jiang et al., 2020). Kim and Roh (2017) proposed that there are mixed effects for the origin of a bachelor’s degree on US-trained Korean PhDs. In Korea, the source of a bachelor’s degree is significant, as social networks between PhDs and faculty are established through undergraduate study. By contrast, in the US, the origin of the bachelor’s degree does not significantly affect the hiring process (Kim & Roh, 2017). This study determines whether an undergraduate degree from a top university can provide a cumulative advantage:

Hypothesis 2.2:

Japanese-trained Chinese PhDs who have matriculated in an undergraduate program at a top university in China tend to have a more successful academic career than those who have not.

Mobility factors

The factors associated with transnational mobility are worth analyzing. The first is the type of doctoral study that was conducted overseas. Mobility for doctoral study can be categorized into temporary mobility and mobility involving the entire degree program (Teichler, 2015). The CSC sponsors Chinese students to study abroad either as formal doctoral students or temporary visiting students. Most previous studies on the transnational mobility of Chinese PhD students discuss both patterns (Horta et al., 2020; Jiang & Shen, 2019; Jiang et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2017). Wang and Shen (2020) examined the accumulation of social capital by Chinese PhD students and the establishment of international Sino–Swiss collaborative relationships across different types of study experience in Switzerland. Zweig et al. (2004) reported that, although overseas experience could help domestic Chinese PhDs establish global networks, those who returned with doctoral degrees from foreign institutions substantially increased their human capital and internalized their training overseas. Few studies have compared outcomes across different types of Chinese PhD students’ doctoral mobility are limited. This study was designed to test the following hypothesis to fill this research gap:

Hypothesis 3.1:

Chinese researchers who have studied in Japan as full-time doctoral students are more likely to have more successful academic careers than those who have studied in Japan as visiting students.

The duration of the stay is another important dimension of the transnational study experience. Kyvik et al. (1999) found that a long sojourn abroad was an important means of achieving positive effects of international orientation in one’s doctoral education. However, Eduan (2017) indicated that the duration of study abroad is irrelevant to the PhDs’ future international academic collaboration. By contrast, Horta et al. (2020) reported that where the duration of the international stays was too long, the marginal gains in the ability to engage in new collaborations and publish in high-impact journals declined. Due to these mixed results regarding the significance of the duration of the stay abroad, this study tests the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.2:

The duration of Chinese scholars’ doctoral study in Japan has a significant and positive impact on their academic study.

Supervisor factors

The early literature (e.g., Long & McGinnis, 1985; Reskin, 1977) in the sociology of science validates the significance of supervisors for the academic training and the development of doctoral students’ careers. This study also examines supervisors’ influence on the academic careers of transnationally mobile PhD students.

Jin et al. (2007) identified the importance of ethnic ties in the establishment of international collaborative relationships, and supervisors’ ethnicities also impact the outcomes of overseas doctoral studies (Jiang & Shen, 2019; Shen et al., 2017). Jiang and Shen (2019) found that more than 60% of European-trained Chinese PhD returnees had co-authored publications with their supervisors. A shared Chinese ethnicity significantly affected returnees’ co-authorships on their arrival in China. Shen et al. (2017) found that Chinese PhD students who studied in Europe under ethnic Chinese supervisors received greater academic support from their supervisors than those who were mentored by non-Chinese scholars. Ethnic Chinese supervisors contribute to overseas Chinese doctoral students’ academic output, at least in terms of their international collaborative publications, which may benefit their academic careers. This study explores whether the supervisor’s ethnicity matters for Japanese-trained Chinese PhD returnees by testing the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.1:

Chinese scientists who have conducted their doctoral studies in Japan under the supervision of scholars of Chinese ethnicity tend to have had more successful academic careers than those who have not.

This study also considers the supervisors’ academic ranks. Supervisors’ academic performance and international professional ties are essential for early career scholars (e.g., Bauder, 2020; Miller et al., 2005). Academic rank is among the more effective indicators of a scholar’s academic eminence and social capital, as it represents lead roles on teams, integration into the scholarly community, the capacity for organizational decision-making, and the levels of academic productivity (Fox, 2020). Supervisors with high academic rank are expected to be endowed with a greater ability to train their graduate students. However, few studies have paid close attention to the relationship between overseas supervisors’ academic ranks and international PhD students’ academic career success. The present study fills this gap by testing the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.2:

Chinese scientists who have conducted their doctoral studies in Japan under the supervision of scholars with full professorships tend to have more successful academic careers than those who have not.

This study also considers PhDs’ co-publications with their supervisors in Japan. Several studies of PhDs’ academic careers argue that co-authorship with a supervisor provides a PhD student with a valuable opportunity in learning how to conduct and present original research and to gain experience in academic writing and publishing (Broström, 2019; Pinheiro et al., 2014). This practice forms a signal to the scientific community that doctoral students can contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the form of publishing while still at an early stage in their career, acquainting them with the underlying rules of academia (Jung et al., 2021). Shen (2018) empirically verified that visiting Chinese doctoral students’ co-publications with their host supervisors increased the students’ research productivity and provided them with high-quality academic supervision. This study tests the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.3:

Chinese scientists who have conducted their doctoral studies in Japan and co-published with their host supervisors tend to have had more successful academic careers than those who have not.

Methodology

Data

This study draws on CSC dataset that contains demographic information on and educational backgrounds for the entire group of 2193 Chinese PhDs who were funded to study in Japan as doctoral students, whether full-time or visiting, from 2008 to 2014. The original dataset contained basic information, including date of birth, gender, and discipline, the university where the doctorate was awarded, the university where the PhD was funded to study in Japan, the type and length of the mobility, and the name and academic rank of the host supervisor in Japan.

PhDs in science-stream disciplines—the natural sciences, engineering, the agricultural sciences, and the medical sciences—currently working as university faculty in mainland China were the sample for this study. We draw on the understanding of Yonezawa et al. (2016) to focus on internationally mobile Asian scholars in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Researchers’ training in science-stream fields depends on the availability of significant resources, including funding and equipment. The limited availability of such resources in developing countries is a crucial motivating factor for PhD students in science-stream fields to enable greater mobility relative to their counterparts in the humanities and social sciences. In addition, as academic publications in science-stream fields are predominantly written in a universal language, they exhibit a high degree of global standardization. This justifies the use of a number of international journal articles as a measure of pre-graduation academic productivity for PhD students in science-stream fields. In the further analysis, additional information on grantees was collected. First, the authors searched for all of the PhDs’ current employment status, including countries and names of institutions of their current positions. A total of 684 PhDs from our search were currently employed by Chinese universities.

The authors supplemented the educational backgrounds for the PhDs with matching employment information, including the universities where they obtained their bachelor’s degrees, the ethnicities of their supervisors in Japan, and their publications before graduation. These data were retrieved from Scopus, the largest database of abstracts and citations for peer-reviewed academic literature.

Measurements

Several dimensions have been employed in previous studies to measure individual scholars’ career attainments, such as participation in an academic profession, employment at prestigious institutes, the attainment of a senior academic rank, and the quantity and quality of publications (Cole & Cole, 1967; Long & Fox, 1995). This study focuses on academic employment at a top university in China for a marker of achievement. This is of symbolic and instrumental significance, as it rewards past achievement and facilitates further research (Zuckerman, 1970). Accordingly, whether a PhD holder has an academic position in a Project 211 university in China was used as a dependent variable. Project 211 is a national higher-education initiative being implemented by the Chinese government in 1995. This project provides support to 112 universities to elevate them to international contemporary teaching and research standards. Thanks to the strong financial support provided from the government, Project 211 universities are outperforming other universities in terms of the quality of their faculties, facilities, and students (Hu & Wu, 2021). Thus, a position at a Project 211 university means that one has a post at a top Chinese university.

The number of internationally peer-reviewed journal articles with a future PhD graduate as the first or corresponding author published before the completion of the graduate’s doctoral study was adopted as a continuous variable.

Two dummy variables were used to measure the prestige of the institution where the PhDs received their training. The first measured whether it was a Global 30 (G30) university in Japan (with non-G30 universities as the reference group). This factor relates to the Japanese government’s G30 Project, launched in 2009, undertaken to provide a number of core universities with additional support to enhance their level of internationalization. In all, 13 universities were selected for this project. Given that the indicators for selection closely resembled those adopted by the global university rankings, the G30 Project has been recognized as an effective proxy for world-class Japanese universities (Yonezawa, 2013). The second dummy variable regarded whether the PhD had conducted their undergraduate study at a Project 211 university in mainland China (non-Project 211 universities were used as the reference group). This variable forms the dependent variable for whether a PhD is currently working for a Project 211 university, in turn a proxy for elite universities in mainland China.

The duration of the study, a continuous variable, measures the number of months that the PhD spent studying as a doctoral student in Japan. The type of PhD (a dummy variable with visiting doctoral student as the reference group) was used to indicate whether the PhD studied in Japan full-time or as a visiting doctoral student.

The PhDs’ supervisors in Japan were classified according to three dummy variables: supervisor’s ethnicity (with non-Chinese supervisors as the reference group), supervisor’s rank (with non-full professors as the reference group), and pre-graduation co-publication (with no publication with the PhD student as the reference group).

Four control variables were used in the study. Several studies have reported the (re)production of gender inequality among international PhDs. This comes about because female doctoral students are more vulnerable than male ones in transnational academic mobility, and their integration into international academic networks is more difficult (Horta et al., 2020; Jöns, 2011; Mählck, 2018). Thus, gender (a dummy variable with female as the reference group) was controlled for in the analysis. Two continuous variables related to time were also adopted, namely, the age of the PhD student (as of April 30, 2023) and the year when they obtained their doctorate. Studies of the sociology of science have typically found that the distinction between individual scientists in terms of academic attainments become more pronounced with time, which refers to the reality of the phenomenon of cumulative advantage in the scientific community (e.g., Allison & Stewart, 1974; Mittermeier & Knorr, 1979; Allison et al., 1982). The PhDs students’ disciplines (including natural science, engineering, agronomy, and medicine) were included as control variables because academic practices, including employment and publications, can significantly vary by academic discipline (Becher & Trowler, 2001). Table 1 presents the definitions of the variables mentioned above.

Results

Descriptive analysis

As seen in Table 2, the descriptive statistics show that approximately 65% of the PhD graduates found an academic position in a Project 211 university in China. Approximately 75% of PhDs obtained their bachelor’s degrees from a top mainland Chinese university, and 64% received funded to study for their doctoral degrees at a G30 university. Approximately 69% studied in Japan as full-time doctoral students, and they spent approximately 35 months in Japan on average. Approximately 13% were supervised by scientists of Chinese ethnicity, and more than 80% of supervisors were already full professors before the Chinese PhD students arrived. Approximately 65% of PhDs had co-published at least one academic article with their supervisors in Japan before completing their doctoral studies. The mean age of the PhDs in the sample was 38 years as of April 30, 2023, and almost 70% of them were male. Most (74%) majored in engineering, and approximately 16% majored in a natural science. Approximately 5% studied agronomy and medicine.

The authors compared differences across the employment outcomes of the PhDs as the independent variables. The PhD students who went on to find academic positions at top universities had higher pre-graduation academic productivity (M = 5.96, SD = 6.705) than those who did not find a position at a top university (M = 4.73, SD = 5.409) in China (t = 584.373, p < 0.05). The proportion of PhDs working at Project 211 universities did not differ by rank of supervisor (χ2 = 3.221, p > 0.05) or by pre-graduation co-publication (χ2 = 1.285, p > 0.05). PhDs who had different educational backgrounds showed had significant differences in their employment outcomes. Those who were funded to study in a G30 university in Japan (χ2 = 3.975, p < 0.05) and obtained a bachelor’s degree from a Project 211 university in China (χ2 = 45.175, p < 0.05) showed a greater likelihood of acquiring an academic position at a Project 211 university in China. In addition, the PhDs who studied as full-time doctoral students (χ2 = 5.549, p < 0.05) and under the supervision of scholars of Chinese ethnicity (χ2 = 5.098, p < 0.05) were more likely to find an academic position at a Project 211 university in China.

Regression analysis

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine whether the PhD students’ employment outcomes conformed to the norm of universalism, and the results are shown in Table 3. Model 1 is the full model, including all of the variables, and the data for the PhDs who studied in Japan as full-time and visiting doctoral students are analyzed separately in Models 2 and 3.

The number of articles published before completing the doctorate significantly increased the probability of finding a position at a top university (Models 1 and 2), which supports Hypothesis 1. This result supports the norm of universalism, according to which a scientist should receive rewards commensurate with their original contributions to the advancement of science (Merton, 1973). Universalism holds that it is fair for relatively highly productive PhDs to acquire positions at top universities as a form of reward from the scientific community. However, pre-graduation productivity shows a nonsignificant effect when only the PhDs who studied in Japan as visiting doctoral students were examined (Model 3). This means that the norm of universalism cannot entirely explain PhDs’ academic attainments in terms of obtaining a position in a prestigious university. Moreover, other factors beyond academic productivity may influence their employment, as examined below.

Having done doctoral study at a G30 university did not affect the probability of employment at a top university in China (Models 1–3), so Hypothesis 2.1 was rejected. However, the prestige of the university where the PhDs obtained their bachelor’s degrees did significantly influence the probability of ultimately being employed by a top university in China (Models 1–3), which supports Hypothesis 2.2. The undergraduate university indicates that whether a Japanese-trained Chinese PhD could find an academic position at a top university in China could not be explained by the norm of universalism.

Among the mobility factors, only visiting employment at a top university was significantly influenced by the duration of the study in Japan (Model 3), which supports Hypothesis 3.2. For those who were funded to study in Japan for a shorter period, the longer their sojourn, the higher the likelihood of their finding a position at a top university. The type of mobility did not show statistical significance for the PhDs’ employment outcomes, so Hypothesis 3.1 was rejected.

Of all of the factors related to the host supervisors in Japan during the doctoral study, only Chinese ethnicity significantly impacted the PhDs’ employment at a top university (Model 1), which supported Hypothesis 4.1. If a PhD studied in Japan as a full-time doctoral student and under the supervision of a scholar of Chinese ethnicity, they were more likely to be employed at a top university in China (Model 2). Further, whether the supervisor was of Chinese ethnicity was not statistically significant for visiting PhDs (Model 3). Meanwhile, employment at a top university was not influenced by whether the PhD student received supervision from a full professor in Japan or had co-published at least one article with their supervisor.

Conclusions and discussion

This study explored the factors contributing to the stratification of career attainments of Chinese PhDs who were funded by the CSC to pursue doctoral studies in Japan using the norm of universalism. We examined whether this norm could explain the PhDs’ employment outcomes or whether factors other than academic productivity in their employment exist.

The norm of universalism was found able to partially explain the PhDs’ employment outcomes, broadly speaking. The reason for this is that a high number of publications before employment enhanced the likelihood of acquiring an academic job at a top university back in China. However, separate analyses were conducted found that the norm of universalism could partially explain employment outcomes for full-time PhDs but not for visiting PhDs. The findings partly confirm the effective functioning of the norm of universalism in China’s academia, which states that academic positions at prestigious institutions should be allocated in a meritocratic way. As Jiang et al. (2020) noted, academic productivity is a significant recruitment criterion at elite research universities because the Chinese government has placed great hopes on the academic capacity of PhDs who were trained outside mainland China. Returning Chinese PhDs are expected to demonstrate their ability to publish articles before seeking faculty positions at top universities. However, Long (1978) noted that cross-sectional study is insufficient for examining the relationships between academic productivity and academic position, and longitudinal study is required. Thus, this study should be extended to develop a longitudinal analysis of internationally mobile Chinese PhDs to explore how interdependent relationships between the two factors change over the course of an academic career and with transnational mobility experience.

Whether a PhD studied for their doctoral degree at a G30 university had no significant impact on their subsequent career attainments, measured by their employment at a Project 211 university in China. This result is consistent with the findings of Jiang et al. (2020), that is, PhDs’ host universities, independent of their academic productivity, had no prestige effect. However, the results indicated that the prestige of the Chinese university where the PhDs had obtained their bachelor’s degree was critical for their subsequent academic career on their return to China, which is consistent with the findings of Kim and Roh (2017). Kim and Roh (2017) found that, for Korean graduate students who received at least their undergraduate degree at a Korean university followed by additional graduate education in the US, the academic labor markets showed a distinct emphasis on undergraduate origin in the hiring process. Kim and Roh (2017) noted that Korean academia emphasized doctoral and undergraduate origins, as social networks between candidates and faculty were linked through undergraduate origins. The Japanese-trained Chinese PhDs who found positions at top universities may have indeed effectively established social networks in the Chinese academia, which was important for academic employment in China. However, given the limitations of our data, further analysis is required to clarify how undergraduate experience at a top university functions in terms of the selection (Allison & Long, 1990) and departmental (Allison & Long, 1990) effects of social capital (Burris, 2004).

The finding that whether a PhD student was in Japan as a full-time or visiting doctoral student is not significant for future employment opportunities at a top university in China previous existing studies (Wang & Shen, 2020; Zweig et al., 2004). Zweig et al. (2004) note that, although domestic PhDs can establish global networks through transitory overseas stays, Chinese returnees who return with a PhD from abroad showed increased human capital and substantially internalized their overseas training. There may be no distinct gap in the quality of doctoral education in Japan and China, and therefore, the competitiveness of those with doctoral degrees from Japan or China may be equally highly regarded in the Chinese academic labor market. Figure 2 indicates the number of universities listed among the global top 500 in Japan and mainland China. From these data, China’s number of world-class universities surpassed Japan’s in 2012. Yonezawa et al. (2016) also highlighted the strengthening of self-contained mobility patterns among Chinese academics during the 2000s. This result indicates a substantial increase in the proportion of Chinese academics who have obtained their bachelor’s and doctoral degrees in China. Thus, thanks to the prominent development of Chinese higher-education institutions in both scale and quality, returnee PhDs have less of an advantage over their domestic counterparts than they used to. A future study will consider Chinese PhDs who have no mobility experience in Japan to compare the human capital that they accumulate before obtaining doctoral degrees.

However, the duration of doctoral study in Japan was a positive predictor for the likelihood that a visiting doctoral student would obtain a position at a top university in China. Kyvik et al. (1999) proposed that longer academic visits abroad by PhD students are rewarding in terms of composing dissertations, acquiring general research qualifications, and developing personally. For Chinese visiting doctoral students in Japan, spending a longer time in their doctoral studies could help them improve their abilities to make them stand out in the hiring process back in China. Moreover, Horta et al. (2020) noted the importance of a long academic sojourn abroad in the formation of international, academic, and collaborative relationships. Chinese visiting PhDs who had spent a long period in Japan managed to develop international academic networks utilized to enhance the likelihood of being hired at a top university. Further analysis will elaborate the relationship between the time spent in Japan and the formation of international academic networks.

Regarding the factors related to host supervisors in Japan, their Chinese ethnicity effectively predicted the PhDs’ academic career success. Jin et al. (2007) proposed the term “Overseas Chinese Phenomenon,” referring to the fact that scientists of Chinese descent play an important role in international collaborations between mainland China and the rest of the world. This may relate to the importance of the supervisors of Chinese ethnicity in Japan found in our study. Zheng (2019) found that, the relationship between Chinese doctoral students funded by the CSC in Finland and their supervisors was formal and professional, as they were solely funded by the CSC. Chinese doctoral students often felt a sense of loss due to the nature of this type of relationship, particularly as the family logic of supervisor–supervisee was embedded in them. Supervisors of Chinese ethnicity who had a shared cultural background and common language could be in favor of the family logic, which presents a close and informal relationship with students. This relationship likely further contributed to the high competitiveness of Japanese-trained PhDs in seeking employment at top universities in China. In addition, scholars of Chinese descent could already have established social networks in Chinese academia that could be utilized to assist their students in finding positions at prestigious institutions. These potential advantages owing to supervisors of Chinese ethnicity require further empirical examination.

This study has implications for various stakeholders in the systems of higher-education and academic communities in China and Japan. First, norms of universalism may not fully explain employment outcomes of foreign-trained Chinese PhDs, implying discrimination in the academic community. Taking into account the long-run development of the national scientific and innovative capacity, higher-education institutions are expected to strategically evaluate whether PhDs having graduated from prestigious universities have already demonstrated or can develop outstanding academic performance to match preferential rewards. Second, this study provides Japan’s higher-education institutions with future directions to enhance the quality of their international doctoral education. The importance of supervisors’ ethnicity may relate to the language and cultural barriers between Japanese supervisors and Chinese PhD students. Japan has sought to enhance the level of the internationalization of its higher-education sectors, including its doctoral education. Thus, the level of internationalization and teaching ability of the Japanese faculties in universities should be improved.

This study has the following limitations. The regression analysis does not establish any causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables. First, possible confounding factors, including academic networks with scholars based in China (Horta et al., 2020) and other characteristics of host supervisors abroad (Shen et al., 2017), were considered. We sought to incorporate additional potential factors for the analysis of career development of international PhDs to reach a deeper understanding of transnational academic mobility among early stage researchers. Second, future studies should seek to employ additional rigorous statistical methodologies, such as longitudinal analysis, to establish causal relationships between the variables.

References

Aksnes, D. W., Rorstad, K., Piro, F. N., & Sivertsen, G. (2013). Are mobile researchers more productive and cited than non-mobile researchers? A large-scale study of Norwegian scientists. Research Evaluation, 22(4), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvt012

Allison, P. D., & Long, J. S. (1987). Interuniversity mobility of academic scientists. American Sociological Review, 52(5), 643–652. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095600

Allison, P. D., & Long, J. S. (1990). Departmental effects on scientific productivity. American Sociological Review, 55(4), 469–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095801

Allison, P. D., Long, J. S., & Krauze, T. K. (1982). Cumulative advantage and inequality in science. American Sociological Review, 47(5), 615–625. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095162

Allison, P. D., & Stewart, J. A. (1974). Productivity differences among scientists: Evidence for accumulative advantage. American Sociological Review, 39(4), 596–606. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094424

Avveduto, S. (2010). Mobility of PhD students and scientists. In P. Peterson, E. Baker, & B. McGaw (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Education (3rd ed., pp. 286–293). Elsevier.

Baldi, S. (1995). Prestige determinants of first academic job for new sociology Ph.D.s 1985–1992. The Sociological Quarterly, 36(4), 777–789. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1995.tb00464.x

Bauder, H. (2020). International mobility and social capital in the academic field. Minerva, 58(3), 367–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-020-09401-w

Becher, T. (2001). P Trowler. Intellectual Enquiry and the Culture of Disciplines McGraw-Hill Education New York: Academic ribes and Territories.

Broström, A. (2019). Academic breeding grounds: Home department conditions and early career performance of academic researchers. Research Policy, 48(7), 1647–1665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.03.009

Burris, V. (2004). The academic caste system: Prestige hierarchies in PhD exchange networks. American Sociological Review, 69(2), 239–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240406900205

Cao, C. (2008). China’s brain drain at the high end: Why government policies have failed to attract first-rate academics to return. Asian Population Studies, 4(3), 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730802496532

Cao, C., Baas, J., Wagner, C. S., & Jonkers, K. (2020). Returning scientists and the emergence of China’s science system. Science and Public Policy, 47(2), 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scz056

Cole, S., & Cole, J. R. (1967). Scientific output and recognition: A study in the operation of the reward system in science. American Sociological Review, 32(3), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.2307/2091085

Crane, D. (1965). Scientists at major and minor universities: A study of productivity and recognition. American Sociological Review, 30(5), 699–714. https://doi.org/10.2307/2091138

Eduan, W. (2017). Influence of study abroad factors on international research collaboration: Evidence from higher education academics in sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Higher Education, 44(4), 774–785. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1401060

Fox, M. (2020). Gender, science, and academic rank: Key issues and approaches. Quantitative Science Studies, 1(3), 1001–1006. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00057

Hayhoe, R. (1984). A comparative analysis of Chinese-Western academic exchange. Comparative Education, 20(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305006840200105

Headworth, S., & Freese, J. (2016). Credential privilege or cumulative advantage? Prestige, productivity, and placement in the academic sociology job market. Social Forces, 94(3), 1257–1282. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sov102

Horta, H., Birolini, S., Cattaneo, M., Shen, W., & Paleari, S. (2020). Research network propagation: The impact of PhD students’ temporary international mobility. Quantitative Science Studies, 2(1), 129–154. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00096

Horta, H., & Santos, J. M. (2016). The impact of publishing during PhD studies on career research publication, visibility, and collaborations. Research in Higher Education, 57(1), 28–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-015-9380-0

Hu, A., & Wu, X. (2021). Cultural capital and elite university attendance in China. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 42(8), 1265–1293. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2021.1993788

Hurlbert, J. S., & Rosenfeld, R. A. (1992). Getting a good job: Rank and institutional prestige in academic psychologists’ careers. Sociology of Education, 65(3), 188–207. https://doi.org/10.2307/2112808

Jiang, J., Mok, K. H., & Shen, W. (2020). Riding over the national and global disequilibria: International learning and academic career development of Chinese Ph.D. returnees. Higher Education Policy, 33(3), 531–554. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-019-00175-9

Jiang, J., & Shen, W. (2019). International mentorship and research collaboration: Evidence from European-trained Chinese PhD returnees. Frontiers of Education in China, 14(2), 180–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11516-019-0010-z

Jin, B., Rousseau, R., Suttmeier, R. P., & Cao, C. (2007). The role of ethnic ties in international collaboration: The Overseas Chinese Phenomenon. Proceedings of the ISSI 2007, Madrid, Spain, 427–436.

Jonkers, K., & Tijssen, R. (2008). Chinese researchers returning home: Impacts of international mobility on research collaboration and scientific productivity. Scientometrics, 77(2), 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-007-1971-x

Jöns, H. (2011). Transnational academic mobility and gender. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 9(2), 183–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2011.577199

Jung, J., Horta, H., Zhang, L., & Postiglione, G. A. (2021). Factors fostering and hindering research collaboration with doctoral students among academics in Hong Kong. Higher Education, 82(3), 519–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00664-6

Kim, D., & Roh, J. (2017). International doctoral graduates from China and South Korea: A trend analysis of the association between the selectivity of undergraduate and that of US doctoral institutions. Higher Education, 73(5), 615–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-9984-0

Kim, J. (2016). Global cultural capital and global positional competition: International graduate students’ transnational occupational trajectories. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 37(1), 30–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1096189

Kim, T. (2009). Transnational academic mobility, internationalization and interculturality in higher education. Intercultural Education, 20(5), 395–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675980903371241

Kim, T. (2017). Academic mobility, transnational identity capital, and stratification under conditions of academic capitalism. Higher Education, 73(6), 981–997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0118-0

Knight, J., & Madden, M. (2010). International mobility of Canadian social sciences and humanities doctoral students. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 40(2), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v40i2.1916

Kyvik, S., Karseth, B., & Remme, J. A. (1999). International mobility among Nordic doctoral students. Higher Education, 38, 379–400. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003762411195

Li, F., & Tang, L. (2019). When international mobility meets local connections: Evidence from China. Science and Public Policy, 46(4), 518–529. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scz004

Li, M., Yang, R., & Wu, J. (2018). Translating transnational capital into professional development: A study of China’s Thousand Youth Talents Scheme scholars. Asia Pacific Education Review, 19(2), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-018-9533-x

Li, W., & Collins, C. S. (2014). Chinese doctoral student socialization in the United States: A qualitative Study. FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education, 1(2), 32–57. https://doi.org/10.18275/fire201401021012

Liu, J., Wang, R., & Xu, S. (2021). What academic mobility configurations contribute to high performance: An fsQCA analysis of CSC-funded visiting scholars. Scientometrics, 126(2), 1079–1100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03783-0

Long, J. S. (1978). Productivity and academic position in the scientific career. American Sociological Review, 43(6), 889–908. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094628

Long, J. S., Allison, P. D., & McGinnis, R. (1979). Entrance into the Academic career. American Sociological Review, 44(5), 816–830. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094529

Long, J. S., & Fox, M. F. (1995). Scientific Careers: Universalism and particularism. Annual Review of Sociology, 21, 45–71. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.21.080195.000401

Long, J. S., & McGinnis, R. (1985). The effects of the mentor on the academic career. Scientometrics, 7(3–6), 255–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02017149

Lu, X., & McInerney, P.-B. (2016). Is it better to “Stand on Two Boats” or “Sit on the Chinese Lap”?: Examining the cultural contingency of network structures in the contemporary Chinese academic labor market. Research Policy, 45(10), 2125–2137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2016.09.001

Lu, X., & Zhang, W. (2015). The reversed brain drain: A mixed-method study of the reversed migration of Chinese overseas scientists. Science, Technology and Society, 20(3), 279–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971721815597127

Mählck, P. (2018). Vulnerability, gender and resistance in transnational academic mobility. Tertiary Education and Management, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2018.1453941

Melkers, J., & Kiopa, A. (2010). The social capital of global ties in science: The added value of international collaboration. Review of Policy Research, 27(4), 389–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.2010.00448.x

Meng, S. (2020). The impact of the transnational mobility experience in Japan on the Academic Performance of Chinese Scientists. The Journal of Management and Policy in Higher Education, 10, 53–69. https://doi.org/10.51019/daikei.10.0_53

Merton, R. (1957). Priorities in scientific discovery: A chapter in the sociology of science. American Sociological Review, 22(6), 635–659.

Merton, R. (1973). The Sociology of Science: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations. University of Chicago Press.

Miller, C. C., Glick, W. H., & Cardinal, L. B. (2005). The allocation of prestigious positions in organizational science: Accumulative advantage, sponsored mobility, and contest mobility. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(5), 489–516. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.325

Mittermeir, R., & Knorr, K. D. (1979). Scientific productivity and accumulative advantage: A thesis reassessed in the light of international data. R&D Management, 9(s1), 235–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.1979.tb01302.x

Nerad, M. (2010). Globalization and the internationalization of graduate education: A macro and micro view. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 40(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v40i1.1566

Pinheiro, D., Melkers, J., & Youtie, J. (2014). Learning to play the game: Student publishing as an indicator of future scholarly success. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 81, 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2012.09.008

Reskin, B. F. (1977). Scientific productivity and the reward structure of science. American Sociological Review, 42(3), 491–504. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094753

Shen, W. (2018). Transnational research training: Chinese visiting doctoral students overseas and their host supervisors. Higher Education Quarterly, 72(3), 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12168

Shen, W., & Jiang, J. (2021). Institutional prestige, academic supervision and research productivity of international PhD students: Evidence from Chinese returnees. Journal of Sociology, 59(2), 552–579. https://doi.org/10.1177/14407833211055225

Shen, W., Liu, D., & Chen, H. (2017). Chinese Ph.D. students on exchange in European Union countries: Experiences and benefits. European Journal of Higher Education, 7(3), 322–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2017.1290885

Shen, W., Wang, C., & Jin, W. (2016). International mobility of PhD students since the 1990s and its effect on China: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 38(3), 333–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2016.1174420

Teichler, U. (2015). Academic mobility and migration: What we know and what we do not know. European Review, 23(S1), S6–S37. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798714000787

Wang, X., & Shen, W. (2020). Studying abroad, social capital, and Sino-Swiss scientific research collaboration: A study of Chinese scholars studying in Switzerland. International Journal of Chinese Education, 9(2), 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1163/22125868-12340128

Wu, R. (2017). Academic socialization of Chinese doctoral students in Germany: Identification, interaction and motivation. European Journal of Higher Education, 7(3), 276–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2017.1290880

Yang, R. (2020). Benefits and challenges of the international mobility of researchers: The Chinese experience. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 18(1), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2019.1690730

Yonezawa, A. (2013). Challenges for top Japanese universities when establishing a new global identity: Seeking a new paradigm after “World Class.” In J. C. Shin & B. M. Kehm (Eds.), Institutionalization of World-Class University in Global Competition (pp. 125–143). Springer.

Yonezawa, A., Horta, H., & Osawa, A. (2016). Mobility, formation and development of the academic profession in science, technology, engineering and mathematics in East and South East Asia. Comparative Education, 52(1), 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2015.1125617

Zheng, G. (2019). Deconstructing doctoral students’ socialization from an institutional logics perspective: A qualitative study of the socialization of Chinese doctoral students in Finland. Frontiers of Education in China, 14(2), 206–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11516-019-0011-y

Zuckerman, H. (1967). Nobel laureates in science: Patterns of productivity, collaboration, and authorship. American Sociological Review, 32(3), 391–403. https://doi.org/10.2307/2091086

Zuckerman, H. (1970). Stratification in American science. Sociological Inquiry, 40(2), 235–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1970.tb01010.x

Zweig, D. (2006). Competing for talent: China’s strategies to reverse the brain drain. International Labour Review, 145(1–2), 65–90.

Zweig, D., Changgui, C., & Rosen, S. (2004). Globalization and transnational human capital: Overseas and returnee scholars to China. The China Quarterly, 179, 735–757. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741004000566

Zweig, D., & Wang, H. (2013). Can China bring back the best? The Communist Party organizes China’s search for talent. The China Quarterly, 215, 590–615. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741013000751

Funding

Open access funding provided by The University of Tokyo. This work was supported by RIHE Open-call research, Grant Number RIHED02001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

The Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo has informed that based on the contents of the submitted article, the authors can automatically obtain the ethical approval from the committee as long as they guarantee the appropriate process and protection of all the data and personal information. The authors have guaranteed the requirement and elaborated the ways how to realize it.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, S., Shen, W. Determinants of Japanese-trained Chinese PhDs’ academic career attainments. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. 25, 925–937 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-023-09911-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-023-09911-8