Abstract

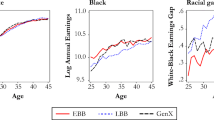

This paper tests an explanation of the “net black advantage,” a widespread but under-theorized finding that shows among people with similar socioeconomic status, black Americans achieve higher levels of education than whites. The proposed theory hypothesizes that blacks’ superior net investment is a response to disadvantage in the labor market; simply, whites have less need for education. The hypothesis is tested using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, when respondents were approximately 29 years old. Results show that among equally qualified individuals: (1) at equal levels of income, black workers have more education than whites (or equivalently, at equal levels of education, whites have higher income); (2) black Americans have a steeper rate of return to educational investment, thus at “some graduate school” or more, there is parity in wages; and (3) non-net rates show that 90% of black respondents have levels of education that are associated with white income advantage, even among equally qualified people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As of this writing, Wave IV is the most recent Add Health release. Wave V is underway, with data collection scheduled to be completed by the end of 2018. See http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design/wave-v-1.

Responses to “best guess” of income and household income questions were given in categories of dollars (e.g., less than $5000; $5000–$9999; etc.) rather than in actual dollars. In order to use the values to replace personal income’s missing values, the midpoint (in dollars) of each category was used.

The Peabody is a standardized receptive vocabulary test that has high correlations with traditional tests of the intelligence quotient. Grade point average (GPA) reflects the respondent’s grades in the four main subjects (mathematics, English language arts, social studies, and science) in the marking period just prior to the Wave I in-home interview. In the Wave IV memory tests, Add Health read a list of 15 words to each respondent. Immediately after hearing the list, respondents were asked to recall as many words as they could in 90s. Then, later in the interview, respondents were asked again to recall as many words as they could, this time in 60s. The number of words recalled correctly each time was entered into the Cronbach’s alpha calculation. The final item in the ability scale involved recall of numbers. Also from Wave IV, the interviewer would read a string of numbers, and the respondent would have to repeat them back in reverse order. Over successive trials, different strings using different numbers were given, and the strings got longer by one number each time. The test concluded when the string became so long that the respondent could not correctly restate the numbers in reverse order. The respondent’s score is the number of trials completed successfully.

After applying the above-described race categorization to the sample, but before limiting it to black and white respondents, the sample was 68% white, 16% black, 11% Hispanic, 3% Asian, and 2% “other.”

Ability for the full Wave IV sample (unweighted N = 14,799) had a mean of 0.00 with a standard deviation of 0.68. As Table 1 shows, for the estimation sample, the mean is 0.07 (SD = 0.65).

All equations reflect design-based modeling, including degrees of freedom (Chantala and Tabor 2010).

Parent income, and personal income, are both right skewed. In all models where they are used as independent variables, substituting their natural log, or alternatively their quadratic function and main effect, does produce statistically significant curvilinearity; however, using the untransformed predictors does not change the paper’s interpretations in any way. In fact, using them untransformed produces more conservative estimates of the outcome. Since the results are not substantively different, the untransformed measures are used to preserve the metrics and produce easily interpretable results.

Personal income has a sizable positive skew, and as a dependent variable (Models 5–8) it does violate the OLS assumption of normality of the error distribution; however, the skew does not change the substantive results that are presented here. In models not shown, the following diagnostic changes were made (in separate models): (1) Models were run using the natural log of personal income as the outcome. (2) An increasingly popular alternative to logging skewed-dependent variables (as long as they have only positive values) is to use Poisson regression with robust standard errors (Wooldridge 2010; and see; Gould 2011 for a summary). The technique was deployed here as a diagnostic tool. (3) The OLS analyses were rerun, except respondents with personal incomes above $80,000 were eliminated (thereby making personal income normally distributed). In all cases for these various diagnostic models, the coefficients for the key variables all retained the same signs with similar magnitudes, and none fell in or out of significance. Among covariates, there were changes in significance of the location dummy variables, but as a whole each larger concept (region and urbanicity) retained significance. Given this paper’s desire to create directly comparable models that predict education and then income, and the benefit of maintaining meaningful metrics and coefficients (rather than resorting to log dollars or changes in odds), the decision was made to use OLS regression. The results herein are robust; substantive interpretations do not change based on the type of model used.

Figure 1 black–white income comparisons, adjusted Wald tests: Edu level 1: F(1, 128) = 11.13, p = .001; Edu level 2: F(1, 128) = 13.65, p < .001; Edu level 3: F(1, 128) = 12.79, p < .001; Edu Level 4: F(1, 128) = 3.31, p = .07; Edu level 5: F(1, 128) = 0.08, ns; Edu level 6: F(1, 128) = 0.23, ns.

References

Agresti, A., & Finlay, B. (2008). Statistical methods for the social sciences (4th edn.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Aldrich, H., Renzulli, L., & Langton, N. (1998). Passing on privilege: Resources provided by self-employed parents to their self-employed children. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 16, 291–317.

Alexander, K., Holupka, S., & Pallas, A. (1987). Social background and academic determinants of two-year versus four-year college attendance: Evidence from two cohorts a decade apart. American Journal of Education, 96(1), 56–80.

Alexander, M. (2012). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York: The New Press.

Bauman, K. (1998). Schools, markets, and family in the history of African-American education. American Journal of Education, 106, 500–531.

Becker, G. (1993). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (3rd edn.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bennett, P., & Lutz, A. (2009). How African American is the net black advantage?: Differences in college attendance among immigrant blacks, native blacks, and whites. Sociology of Education, 82(1), 70–100.

Bennett, P., & Xie, Y. (2003). Revisiting racial differences in college attendance: The role of historically black colleges and universities. American Sociological Review, 68(4), 567–580.

Blau, P., & Duncan, O. (1967). The American occupational structure. New York: Wiley.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. (1979). The inheritors: French students and their relation to culture (R. Nice, Trans). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Brame, R., Bushway, S., Paternoster, R., & Turner, M. (2014). Demographic patterns of cumulative arrest by ages 18 and 23. Crime & Delinquency, 60(3), 471–486.

Bruckmuller, S., & Branscombe, N. (2010). The glass cliff: When and why women are selected as leaders in crisis contexts. British Journal of Social Psychology, 49(3), 433–451.

Budig, M., & England, P. (2001). The wage penalty for motherhood. American Sociological Review, 66(2), 204–225.

Chantala, K., & Tabor, J. (2010). Strategies to perform a design-based analysis using the Add Health data. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Charles, C., Roscigno, V., & Torres, K. (2007). Racial inequality and college attendance: The mediating role of parental investments. Social Science Research, 36(1), 329–352.

Chen, P., & Chantala, K. (2014). Guidelines for analyzing Add Health data. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Cohen, P., & Huffman, M. (2003). Occupational segregation and the devaluation of women’s work across U.S. labor markets. Social Forces, 81(3), 881–908.

Collins, R. (1979). The credential society: A historical sociology of education and stratification. New York: Academic Press.

Conley, D. (2010). Being black, living in the red: Race, wealth, and social policy in America. 10th Anniversary Edition. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Cotter, D., Hermsen, J., Ovadia, S., & Vanneman, R. (2001). The glass ceiling effect. Social Forces, 80(2), 655–682.

Darity, W. (1982). The human capital approach to black-white earnings inequality: Some unsettled questions. The Journal of Human Resources, 17(1), 72–93.

Frank, R., Akresh, I., & Lu, B. (2010). Latino immigrants and the U.S. racial order. American Sociological Review, 75(3), 378–401.

Goldin, C., Katz, L., & Kuziemko, I. (2006). The homecoming of American college women: The reversal of the college gender gap. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(4), 133–156.

Goldsmith, A., Hamilton, D., & Darity, W. (2007). From dark to light: Skin color and wages among African-Americans. The Journal of Human Resources, 42(4), 701–738.

Gould, W. (2011). Use Poisson rather than regress; tell at friend. The Stata Blog. Retrieved from https://blog.stata.com/2011/08/22/use-poisson-rather-than-regress-tell-a-friend/.

Granovetter, M. (1995). Getting a job: A study of contacts and careers (2nd edn.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Grodsky, E., Warren, J., & Felts, E. (2008). Testing and social stratification in American education. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 385–404.

Haslam, S. A., & Ryan, M. (2008). The road to the glass cliff: Differences in the perceived suitability of men and women for leadership positions in succeeding and failing organizations. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(5), 530–546.

Hauser, R. (1993). Trends in college entry among whites, blacks, and Hispanics. In C. Clotfelter & M. Rothschild (Eds.), Studies of supply and demand in higher education (pp. 61–120). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Herrnstein, R., & Murray, C. (1994). The bell curve: Intelligence and class structure in American life. New York: The Free Press.

Hout, M. (2012). Social and economic returns to college education in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 38, 379–400.

Hunter, M. (2005). Race, gender, and the politics of skin tone. New York: Routledge.

Jacobs, J. (2003). Detours on the road to equality: Women, work and higher education. Contexts, 2(1), 32–41.

Jencks, C., & Phillips, M. (Eds.). (1998). The black-white test score gap. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Kane, J., & Spizman, L. (1994). Race, financial aid awards and college attendance: Parents and geography matter. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 53(1), 85–97.

Karlin, C., England, P., & Richardson, M. (2002). Why do ‘women’s jobs’ have low pay for their educational level? Gender Issues, 20(4), 3–22.

Katznelson, I. (2005). When affirmative action was white: An untold history of racial inequality in twentieth-century America. New York: W. W. Norton.

Levanon, A., England, P., & Allison, P. (2009). Occupational feminization and pay: Assessing causal dynamics using 1950–2000 U.S. Census data. Social Forces, 88(2), 865–892.

Mangino, W. (2010). Race to college: The ‘reverse gap.’. Race and Social Problems, 2, 164–178.

Mangino, W. (2012). Why do whites and the rich have less need for education? The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 71(3), 562–602.

Mangino, W. (2014). The negative effects of privilege on educational attainment: Gender, race, class, and the Bachelor’s degree. Social Science Quarterly, 95(3), 760–784.

Mason, P. (1997). Race, culture, and skill: Interracial wage differences among African Americans, Latinos, and whites. Review of Black Political Economy, 25(3), 5–39.

Mason, P. (1998). Race, cognitive ability, and wage inequality. Challenge, 41(3), 63–84.

Massey, D., & Denton, N. (1993). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

McClendon, M. (2002). Multiple regression and causal analysis. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415–444.

Merolla, D. (2013). The net black advantage in educational transitions: An education careers approach. American Educational Research Journal, 50(5), 895–924.

Muller, C., & Schiller, K. (2000). Leveling the playing field? Students’ educational attainment and states’ performance testing. Sociology of Education, 73(3), 196–218.

Oliver, M., & Shapiro, T. (Eds.). (2006). Black wealth/white wealth: A new perspective on racial inequality (2nd edn.). New York: Routledge.

Pager, D. (2003). The mark of a criminal record. American Journal of Sociology, 108(5), 937–975.

Pager, D. (2007). The use of field experiments for studies of employment discrimination: Contributions, critiques, and directions for the future. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 609, 104–133.

Quillian, L. (2006). New approaches to understanding racial prejudice and discrimination. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 299–328.

Reardon, S., & Owens, A. (2014). 60 years after Brown: Trends and consequences of school segregation. Annual Review of Sociology, 40, 199–218.

Renzulli, L., & Aldrich, H. (2005). Who can you turn to? Tie activation within core business discussion networks. Social Forces, 84(1), 323–341.

Roscigno, V., Karafin, D., & Tester, G. (2009). The complexities and processes of racial housing discrimination. Social Problems, 56(1), 49–69.

Royster, D. (2003). Race and the invisible hand: How white networks exclude black men from blue-collar jobs. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Western, B. (2006). Punishment and inequality in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Wooldridge, J. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data (2nd edn.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Acknowledgements

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mangino, W. Income Returns in Early Career: Why Whites Have Less Need for Education. Race Soc Probl 11, 45–59 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-018-9233-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-018-9233-5