Abstract

Despite having a celebrated labor market integration policy, the immigrant–native employment gap in Sweden is one of the largest in the OECD. From a cross-country perspective, a key explanation might be migrant admission group composition. In this study we use high-quality detailed Swedish register data to estimate male employment gaps between non-EU/EES labour, family reunification and humanitarian migrants and natives. Moreover, we test if differences in human capital are able to explain rising employment integration heterogeneity. Our results indicate that employment integration is highly correlated with admission category. Interestingly, differences in human capital, demographic and contextual factors seem to explain only a small share of this correlation. Evidence from auxiliary regressions suggests that low transferability of human capital among humanitarian and family migrants might be part of the story. The article highlights the need to understand and account for migrant admission categories when studying employment integration.

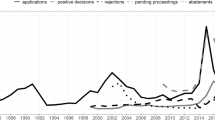

Source: Statistics Sweden

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The labour market integration of refugees can also be impeded on an individual level through the long reach of traumatic experiences.

An anonymous referee made the important point that location choice, and arguably also some of our socio-demographic controls, might be endogenous. For instance, a Stockholm dummy could pick up labour market differences but also transferability and ability through self-selection. This makes a clean interpretation of the county dummy complicated and might also affect our estimates for human capital and transferability. As our study is mainly descriptive, making natives and immigrants comparable with respect to local labour markets is our highest priority.

An anonymous referee pointed out that an alternative strategy would be to include an interaction between education and migration admission category into our pooled regression framework. While we agree that this strategy has merit in an ordinary least squares framework, there are two main reasons why we followed the decomposition approach. First, the marginal effect of an interaction in a probit framework is neither equal to the marginal effect of the interaction term nor constant. Second, instead of interacting only education with admission category, our decomposition can be interpreted as a fully interacted model. Hence, while one can question if the additional effort is worthwhile, we chose the comprehensive approach. A discussion on the arising issue of scaling is given in “Methodology: determinants of employment and employment gap decomposition”.

The contribution is based on weighing each gap. Therefore all contributions sum to 1. For details on the calculation of weights, see Yun (2004).

We also conducted a range of technical robustness checks for decomposition analysis. Our results are robust to a non-pooled framework with either native or immigrant-specific coefficients. Moreover, switching the reference group or accounting for differences in the relative group size produces similar results. However, the contribution of human capital then lies between the Blinder–Oaxaca and Probit results.

The employment rate of immigrants from the Middle East and Africa is 34 percentage points lower than for their native counterparts. For European immigrants the gap is only 14 percentage points.

References

Abdulloev, I., Gang, I., & Yun, M.-S. (2014). Migration, education and the gender gap in labour force participation. European Journal of Development Research, 26, 509–526.

Aydemir, A. (2011). Immigrant selection and short-term labour market outcomes by visa category. Journal of Population Economics, 24(2), 451–475.

Becker, G. S. (1992). Human capital and the economy. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 136(1), 85–92.

Bevelander, P. (2011). The employment integration of resettled refugees, asylum claimants, and family reunion migrants in Sweden. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 30(1), 22–43.

Bevelander, P., & Pendakur, R. (2014). The labour market integration of refugee and family reunion immigrants: A comparison of outcomes in Canada and Sweden. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(5), 689–709.

Bitoulas, A. (2015). Asylum applicants and first instance decisions on asylum applications: 2014. Eurostat Data in Focus 3.

Borevi, K. (2014). Family migration policies and politics understanding the Swedish exception. Journal of Family Issues, 36(11), 1490–1508.

Borjas, G. J. (1994). The economics of immigration. Journal of Economic Literature, 32(4), 1667–1717.

Chin, A., & Cortes, K. E. (2015). The refugee/asylum seeker. In B. Chiswick & P. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of international immigration (Vol. 1). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Chiswick, B., Liang Lee, Y., & Miller, P. W. (2005). A longitudinal analysis of immigrant occupational mobility: A test of the immigrant assimilation hypothesis. International Migration Review, 39(2), 332–353.

Chiswick, B., & Miller, P. W. (1992). Post-immigration qualifications in Australia: Determinants and consequences. Canberra: Bureau of Immigration and Population Research, Australian Government Printing Service.

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (2009). The international transferability of immigrants’ human capital. Economics of Education Review, 28(2), 162–169.

Cobb-Clark, D. A. (2000). Do selection criteria make a difference? Visa category and the labour market status of immigrants to Australia. Economic Record, 76(232), 15–31.

Connor, P. (2010). Explaining the refugee gap: Economic outcomes of refugees versus other immigrants. Journal of Refugee Studies, 23(3), 377–397.

Constant, A., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2005). Immigrant performance and selective immigration policy: A European perspective. National Institute Economic Review, 194(1), 94–105.

Cortes, K. E. (2004). Are refugees different from economic immigrants? Some empirical evidence on the heterogeneity of immigrant groups in the United States. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(2), 465–480.

Dahlstedt, I., & Bevelander, P. (2010). General versus vocational education and employment integration of immigrants in Sweden. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 8(2), 158–192.

De Silva, A. (1997). Earnings of immigrant classes in the early 1980s in Canada: A reexamination. Canadian Public Policy, 23(2), 179–202.

DeVoretz, D. J., Pivnenko, S., & Beiser, M. (2004). The economic experiences of refugees in Canada. IZA discussion paper 1088, Bonn.

Dustmann, C., Fasani, F., Frattini, T., Minale, L., & Schönberg, U. (2017). On the economics and politics of refugee migration. Economic Policy, 32(91), 497–550.

Dustmann, C., & Görlach, J. S. (2016). The economics of temporary migrations. Journal of Economic Literature, 54(1), 98–136.

Edin, P. A., LaLonde, R. J., & Åslund, O. (2000). Emigration of immigrants and measures of immigrant assimilation. Swedish Economic Policy Review, 7, 163–204.

Emilsson, H. (2014). No quick fix: Policies to support the labour market integration of new arrivals in Sweden. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute and International Labour Office.

Emilsson, H. (2016). Recruitment to occupations with a surplus of workers: The unexpected outcomes of Swedish demand-driven labour migration policy. International Migration, 54(1), 5–17.

Emilsson, H., & Magnusson, K. (2015). Högkvalificerad arbetskraftsinvandring till Sverige. In C. Calleman & P. Herzfeld Olsson (Eds.), Arbetskraft från hela världen: hur blev det med 2008 års reform? Delmi Rapport nr: 2015:9 (pp. 72–113). Stockholm.

Eriksson, S. (2010). Utrikes födda på den svenska arbetsmarknaden. In: Vägen till arbete—Arbetsmarknadspolitik, utbildning och arbetsmarknadsintegration. Bilaga 4 till Långtidsutredningen 2011, SOU 2010:88 (pp. 243–389). Stockholm: Fritzes.

Eurostat. (2014). Residence permits for non-EU citizens in the EU28, Eurostat news release 159/2014.

Fortin, N., Lemieux, T., & Firpo, S. (2011). Decomposition methods in economics. In O. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labour economics (Vol. 4). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Friedberg, R. (2000). You can’t take it with you? Immigrant assimilation and the portability of human capital. Journal of Labour Economics, 18(2), 221–251.

Jann, B. (2008). The Blinder–Oaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. The Stata Journal, 8(4), 453–479.

Jasso, G., & Rosenzweig, M. (1995). Do immigrants screened for skills do better than family reunification immigrants? International Migration Review, 29(1), 85–111.

Jasso, G., & Rosenzweig, M. (2009). Selection criteria and the skill composition of immigrants: A comparative analysis of Australian and U.S. employment integration. In J. Bhagwati & G. Hanson (Eds.), Skilled migration today: Phenomenon, prospects, problems, policies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Karlson, K., Holm, A., & Breen, R. (2012). Comparing regression coefficients between same-sample nested models using logit and probit: a new method. Sociological Methodology, 42(1), 286–313.

MIPEX. (2015). Labour market mobility. http://www.mipex.eu/labour-market-mobility. Accessed 30 April 2016.

Nordin, M. (2007). Invandrares avkastning på utbildning i Sverige. IFAU Rapport 2007:10. Uppsala: Institutet för arbetsmarknadspolitisk utvärdering.

Oaxaca, R., & Ransom, M. (1999). Identification in detailed wages decompositions. Review of Economics and Statistics, 81(1), 154–157.

OECD. (2011). Recruiting immigrant workers: Sweden 2011. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2014). International migration outlook 2014. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD/European Union. (2015). Indicators of immigrant integration 2015: Settling in. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Statistics Sweden. (2012). Theme: Education adult learning 2010. Theme report 2012:1. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden.

Szulkin, R., Nekby, L., Bygren, M., Lindblom, C., Russell-Jonsson, K., Bengtsson, R., et al. (2013). På jakt efter framgångsrik arbetslivsintegrering. Stockholm: Institutet för Framtidsstudier.

Wooden, M. (1990). Migrant labour market status. Canberra: Bureau of Immigration Research, Australian Government Printing Service.

Yun, M.-S. (2004). Decomposing differences in the first moment. Economics Letters, 82(2), 275–280.

Yun, M.-S. (2005). A simple solution to the identification problem in detailed wage decompositions. Economic Inquiry, 43(4), 766–772.

Funding

The data used in this study were funded by the Swedish call of the European Integration Fund (Grant No. IF 5-2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luik, MA., Emilsson, H. & Bevelander, P. The male immigrant–native employment gap in Sweden: migrant admission categories and human capital. J Pop Research 35, 363–398 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-018-9206-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-018-9206-y