Abstract

Life-course transitions are important drivers of mobility, resulting in a concentration of migration at young adult ages. While there is increasing evidence of cross-national variations in the ages at which young adults move, the relative importance of various key life-course transitions in shaping these differences remains poorly understood. Prior studies typically focus on a single country and examine the influence of a single transition on migration, independently from other life-course events. To better understand the determinants of cross-national variations in migration ages, this paper analyses for Australia and Great Britain the joint influence of five key life-course transitions on migration: (1) higher education entry, (2) labour force entry, (3) partnering, (4) marriage and (5) family formation. We first characterise the age profile of short- and long-distance migration and the age profile of life-course transitions. We then use event-history analysis to establish the relative importance of each life-course transitions on migration. Our results show that the age structure and the relative importance of life-course transitions vary across countries, shaping differences in migration age patterns. In Great Britain, the strong association of migration with multiple transitions explains the concentration of migration at young adult ages, which is further amplified by the age-concentration and alignment of multiple transitions at similar ages. By contrast in Australia a weaker influence of life-course transitions on migration, combined with a dispersion of entry into higher education across a wide age range, contribute to a protracted migration age profile. Comparison by distance moved reveals further differences in the mix of transitions driving migration in each country, confirming the impact of the life-course in shaping migration age patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For Australia, regions of residence are New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and other (ACT, Northern Territory and Tasmania). For Britain regions of residence are England, Wales and Scotland.

Remoteness is classified into four categories (major city, inner regional, outer regional and remote) based on the statistical local authority of residence.

References

Alderman, H., et al. (2001). Attrition in longitudinal household survey data. Demographic Research, 5(4), 79–124.

Allatt, P. (1993). Becoming privileged: The role of family processes. In I. Bates & G. Riseborough (Eds.), Youth and inequality. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Allison, P. D. (1982). Discrete-time methods for the analysis of event histories. Sociological Methodology, 13(1), 61–98.

Baccaïni, B., & Courgeau, D. (1996). The spatial mobility of two generations of young adults in Norway. International Journal of Population Geography, 2(4), 333–359.

Baxter, J., & Evans, A. (2013). Negotiating the life-course: Stability and change in life pathways. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bell, M., & Muhidin, S. (2009). Cross-national comparisons of internal migration. Human Development Research Paper 2009/30. New York: United Nations.

Bell, M., et al. (2002). Cross-national comparison of internal migration: Issues and measures. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 165(3), 435–464.

Bell, M., Charles‐Edwards, E., Kupiszewska, D., Kupiszewski, M., Stillwell, J., & Zhu, Y. (2015). Internal migration data around the world: Assessing contemporary practice. Population, Space and Place, 21(1), 1–17.

Bernard, A., & Bell, M. (2015). Smoothing internal migration age profiles for comparative research. Demographic Research, 32(33), 915–948.

Bernard, A., Bell, M., & Charles-Edwards, E. (2014a). Improved measures for the cross-national comparison of age profiles of internal migration. Population Studies, 68(2), 179–195.

Bernard, A., Bell, M., & Charles-Edwards, E. (2014b). Life-course transitions and the age profile of internal migration. Population and Development Review, 40(2), 231–239.

Bogue, D. J., Liegel, G., & Kozloski, M. (2009). Immigration, internal migration, and local mobility in the US. Cheltenham: Elgar.

Bongaarts, J. (1978). A framework for analyzing the proximate determinants of fertility. Population and Development Review, 4(1), 105–132.

Borjas, G. J. (1994). The economics of immigration. Journal of Economic Literature, 32(4), 1667–1717.

Bornholt, L., Gientzotis, J., & Cooney, G. (2004). Understanding choice behaviours: Pathways from school to university with changing aspirations and opportunities. Social Psychology of Education, 7(2), 211–228.

Box-Steffensmeier, J. M., & Jones, B. S. (2004). Event history modeling: A guide for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bracken, I., & Bates, J. (1983). Analysis of gross migration profiles in England and Wales: Some developments in classification. Environment and Planning A, 15(3), 343–355.

Buchmann, M. C., & Kriesi, I. (2011). Transition to adulthood in Europe. Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 481–503.

Buck, N. (2000). Using panel surveys to study migration and residential mobility. In D. Rose (Ed.), Researching social and economic change. Routledge: London.

Christie, H. (2007). Higher education and spatial (im) mobility: Nontraditional students and living at home. Environment and Planning A, 39(10), 2445.

Clark, W. A., & Huang, Y. (2003). The life course and residential mobility in British housing markets. Environment and Planning A, 35(2), 323–340.

Courgeau, D. (1985). Interaction between spatial mobility, family and career life-cycle: A French survey. European Sociological Review, 1(2), 139–162.

Corcoran, J., Faggian, A., & McCann, P. (2010). Human capital in remote and rural Australia: The role of graduate migration. Growth and Change, 41(2), 192–220.

DaVanzo, J. (1983). Repeat migration in the United States: Who moves back and who moves on? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 65(4), 552–559.

Dotti, N. F., Fratesi, U., Lenzi, C., & Percoco, M. (2013). Local labour markets and the interregional mobility of Italian university students. Spatial Economic Analysis, 8(4), 443–468.

Duvander, A.-Z. E. (1999). The transition from cohabitation to marriage a longitudinal study of the propensity to Marry in Sweden in the Early 1990s. Journal of Family Issues, 20(5), 698–717.

Easterlin, R. A., Wachter, M. L., & Wachter, S. M. (1978). Demographic influences on economic stability: The United States experience. Population and development review, 4(1), 1–22.

Eicker, F. (1967). Limit theorems for regressions with unequal and dependent errors. In Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability (pp. 59–82). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism (Vol. 6). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Faggian, A., Comunian, R., Jewell, S., & Kelly, U. (2013). Bohemian graduates in the UK: Disciplines and location determinants of creative careers. Regional Studies, 47(2), 183–200.

Faggian, A., McCann, P., & Sheppard, S. (2007). Human capital, higher education and graduate migration: An analysis of Scottish and Welsh students. Urban Studies, 44(13), 2511–2528.

Fitzgerald, J., Gottschalk, P., & Moffitt, R. A. (1998). An analysis of sample attrition in panel data: The Michigan Panel study of income dynamics. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Flowerdew, R., & Al-Hamad, A. (2004). The relationship between marriage, divorce and migration in a British data set. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30(2), 339–351.

Gauthier, A. H. (2007). Becoming a young adult: An international perspective on the transitions to adulthood. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 23(3), 217–223.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Groves, R. M., & Couper, M. P. (1998). Nonresponse in household interview surveys. New York: Wiley.

Grundy, E. (1992). ‘The household dimension in migration research. In A. G. Champion & T. Fielding (Eds.), Migration processes and patterns (Vol. 1, pp. 165–174). London: Research Progress and Prospects, Belhaven.

Gujarati, D., & Porter, D. C. (2009). Basic econometrics. Singapore: McGraw-Hill.

Haapanen, M., & Tervo, H. (2009). Return and onward migration of highly educated: Evidence from residence spells of Finnish graduates. Jyväskylä: School of Business and Economics, University of Jyväskylä.

Heinz, W. R. (1999). From education to work: Cross national perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heuveline, P., & Timberlake, J. M. (2004). The role of cohabitation in family formation: The United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(5), 1214–1230.

Hoare, T. (1991). University competition, student migration and regional economic differentials in the United Kingdom. Higher Education, 22(4), 351–370.

Holdsworth, C. (2006). ‘Don’t you think you’re missing out, living at home?’ Student experiences and residential transitions. The Sociological Review, 54(3), 495–519.

Holdsworth, C. (2009). Going away to uni’: Mobility, modernity, and independence of English higher education students. Environment and Planning. A, 41(8), 1849.

Huber, P.J (1967), ‘The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under non-standard conditions. In Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability (Vol. 1, 221–233) Berkeley: University of California Press.

Inglehart, R., & Baker, W. E. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 19–51.

Ishikawa, Y. (2001). Migration turnarounds and schedule changes in Japan, Sweden and Canada. Review of Urban & Regional Development Studies, 13(1), 20–33.

James, R., Baldwin, G., & McInnis, C. (1999). Which University? The factors influencing the choices of prospective undergraduates. Canberra: Centre for the Study of Higher Education, The University of Melbourne.

Jeon, Y., & Shields, M. P. (2005). The Easterlin hypothesis in the recent experience of higher-income OECD countries: A panel-data approach. Journal of Population Economics, 18(1), 1–13.

Kawabe, H. (1990). Migration rates by age group and migration patterns: Application of Rogers’ migration schedule model to Japan, the Republic of Korea, and Thailand. Tokyo: Institute of Developing Economies.

Kulu, H. (2008). Fertility and spatial mobility in the life course: Evidence from Austria. Environment and Planning A, 40(3), 632–652.

Lindgren, U. (2003). Who is the counter-urban mover? Evidence from the Swedish urban system. International Journal of Population Geography, 9(5), 399–418.

Long, L. (1988). Migration and residential mobility in the United States The Population of the United States in the 1980s. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2005). Measuring and modeling cohabitation: New perspectives from qualitative data. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(4), 989–1002.

Mayer, K. U. (2001). The paradox of global social change and national path dependencies: Life course patterns in advanced societies. In A. E. Woodward & M. Kohli (Eds.), Inclusions and exclusions in European societies (pp. 89–110). London: Routledge.

McCann, P., & Sheppard, S. (2001). Public investment and regional labour markets: the role of UK higher education. In Public investment and regional economic development: essays in honour of Moss Madden (pp. 135–53).

Mills, J. (2006). Student residential mobility in Australia: An expiration of higher education-related migration. St Lucia: The University of Queensland.

Milne, W. J. (1993). Macroeconomic influences on migration. Regional Studies, 27(4), 365–373.

Modell, J., Furstenberg, F., & Hershberg, T. (1976). Social change and transitions to adulthood in historical perspective. Journal of Family History, 1(1), 7–32.

Mortimer, J. T., & Krüger, H. (2000). Pathways from school to work in Germany and the United States. In Handbook of the Sociology of Education (pp. 475–497).

Mulder, C. H. (1993). Migration dynamics: A life course approach. Amsterdam: Thesis Publisher.

Mulder, C. H., & Clark, W. (2002). Leaving home for college and gaining independence. Environment and Planning A, 34(6), 981–1000.

Mulder, C. H., Clark, W. A. V., & Wagner, M. (2002). A comparative analysis of leaving home in the United States, the Netherlands and West Germany. Demographic Research, 7, 565–592.

Mulder, C. H., & Wagner, M. (1993). Migration and marriage in the life course: a method for studying synchronized events. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 9(1), 55–76.

Mulder, C. H., & Wagner, M. (1998). First-time home-ownership in the family life course: A West German–Dutch comparison. Urban Studies, 35(4), 687–713.

Mulder, C. H., & Wagner, M. (2001). The connections between family formation and first-time home ownership in the context of West Germany and the Netherlands. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 17(2), 137–164.

Newbold, K. B. (1997). Primary, return and onward migration in the US and Canada: Is there a difference? Papers in Regional Science, 76(2), 175–198.

Niedomysl, T. (2011). How migration motives change over migration distance: Evidence on variation across socio-economic and demographic groups. Regional Studies, 45(6), 843–855.

Pandit, K. (1997). Demographic cycle effects on migration timing and the delayed mobility phenomenon. Geographical Analysis, 29(3), 187–199.

Patiniotis, J., & Holdsworth, C. (2005). ‘Seize that chance!’ Leaving home and transitions to higher education. Journal of Youth Studies, 8(1), 81–95.

Plane, D. A., & Heins, F. (2003). Age articulation of US inter-metropolitan migration flows. The Annals of Regional Science, 37(1), 107–130.

Rabe, B., & Taylor, M. (2010). Residential mobility, quality of neighbourhood and life course events. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 173(3), 531–555.

Reed, H. E., Andrzejewski, C. S., & White, M. J. (2010). Men’s and women’s migration in coastal Ghana: An event history analysis. Demographic Research, 22(25), 771–812.

Rindfuss, R. R. (1991). The young adult years: Diversity, structural change, and fertility. Demography, 28(4), 493–512.

Rogers, A., & Castro, L. J. (1981), Model migration schedules. In Research Report RR-81-30. Laxenburg, Austria: International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Rothman, S. (2009). Estimating attrition bias in the year 9 cohorts of the longitudinal surveys of australian youth. LSAY Technical Reports (Technical Report No 48).

Sander, N., & Bell, M. (2014). Migration and retirement in the life-course: An event-history approach. Journal of Population Research, 31(1), 1–27.

Shanahan, M. J. (2000). Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: Variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annual review of sociology, 26, 667–692.

Sjaastad, L. A. (1962). The costs and returns of human migration. The Journal of Political Economy, 70(5), 80–93.

Sobotka, T., Skirbekk, V., & Philipov, D. (2011). Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. Population and Development Review, 37(2), 267–306.

Stillwell, J., et al. (2000). A comparison of net migration flows and migration effectiveness in Australia and Britain: Part 1, total migration patterns. Journal of Population Research, 17(1), 17–38.

Uhrig, S. C. (2008) The nature and causes of attrition in the British Household Panel Study. No. 2008-05. ISER Working Paper Series, 2008.

Venhorst, V. A., Van Dijk, J., & Van Wissen, L. (2011). An analysis of trends in spatial mobility of Dutch graduates. Spatial Economic Analysis, 6(1), 57–82.

Warnes, A. M. (1992a). Migration and the life course. In T. Champion & T. Fielding (Eds.), Migration processes and patterns: Research progress and prospects (Vol. 1, pp. 175–187). London: Belhaven Press.

Warnes, A. M. (1992b). Age-related variation and temporal change in elderly migration. In A. Rogers (Ed.), Elderly migration and population redistribution (pp. 35–55). London: Belhaven Press.

Waston, N., & Wooden, M. (2004). Sample attrition in the HILDA survey. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 7(2), 293–308.

Watson, N., & Wooden, M. (2002). Assessing the quality of the HILDA survey wave 1 data. HILDA Project Technical Paper Series (No. 4/02) Melbourne: The University of Melbourne.

Watson, N., & Wooden, M. (2009). Identifying factors affecting longitudinal survey response. Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys, 1, 157–182.

Wrigley, N., et al. (1996). Analysing, modelling and resolving the ecological fallacy. In P. Longley & M. Batty (Eds.), Spatial analysis, modelling in a GIS Environment (pp. 23–40). Cambridge: GeoInformation International.

Yamaguchi, K. (1991). Event history analysis (Vol. 28). Newbury Park: Sage.

Yi, Z., et al. (1994). ‘Leaving the parental home: Census-based estimates for China, Japan, South Korea, United States, France, and Sweden. Population Studies, 48(1), 65–80.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

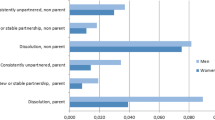

See Fig. 9.

Age profiles of migration by sex. Note: Authors’ calculations based on 1-year interval migration data reported by single-year age groups. Migration data was normalised to sum to unity and smoothed using kernel regression (Bernard and Bell 2015). The x-axis represents single years of age and the y-axis represents migration intensities

Appendix 2

See Table 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bernard, A., Bell, M. & Charles-Edwards, E. Internal migration age patterns and the transition to adulthood: Australia and Great Britain compared. J Pop Research 33, 123–146 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-016-9157-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-016-9157-0