Abstract

Background

Acute stress symptoms can occur while cardiac patients await open-heart surgery (OHS). The distress leads to poor outcomes. This study aimed to investigate the association of sex and psychosocial factors (quality-of-life and character strengths).

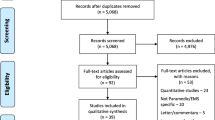

Method

Our study cohort included 481 pre-OHS patients (female 42%; mean age 62 years). Medical indices/factors were obtained from the Society of Thoracic Surgeon’s national database. Multiple regression analyses were performed following pre-planned steps and adjusting medical factors.

Results

Our findings revealed that sex differences in trauma-related symptoms were associated with poor mental well-being, alongside comorbidities. Both mental well-being and comorbidity factors were directly related to acute stress symptoms, while dispositional optimism had an inverse association with this outcome.

Conclusion

To improve OHS outcomes, our findings suggest healthcare providers be attentive to pre-OHS acute stress symptoms, pay greater attention to the emotional well-being of their female patients, and develop supportive interventions to enhance personality strengths.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Cohen BE, Edmondson D, Kronish IM. State of the art review: depression, stress, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(11):1295–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpv047.

Kokoszka A, Bohaterewicz B, Jeleńska K, Matuszewska A, Szymański P. Post-traumatic stress disorder among patients waiting for cardiac surgery. Arch Psychiatry Psychother. 2018;20(2):20–5. https://doi.org/10.12740/APP/91001.

Neupane I, Arora RC, Rudolph JL. Cardiac surgery as a stressor and the response of the vulnerable older adult. Exp Gerontol. 2017;87(Pt):168–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2016.04.019.

Ai AL, Peterson C, Tice TN, et al. The influence of prayer on mental health among cardiac surgery patients: the role of optimism and acute distress symptoms. J Health Psychol. 2007;12(4):580–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105307078164.

Brewin CR, Andrews B, Rose S. Diagnostic overlap between acute stress disorder and PTSD in victims of violent crime. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:783–5. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.783.

Schelling G, Kilger E, Roozendaal B, et al. Stress doses of hydrocortisone, traumatic memories, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in patients after cardiac surgery: a randomized study. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(6):627–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.09.014.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Horst MA, Morgan ME, Vernon TM, et al. The geriatric trauma patient: a neglected individual in a mature trauma system. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89(1):192–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000002646.

Birk J, Kronish I, Chang B, et al. The impact of cardiac-induced post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms on cardiovascular outcomes: design and rationale of the prospective observational reactions to acute care and hospitalizations (ReACH) study. Health Psychol Bull. 2019;3:10–20. https://doi.org/10.5334/hpb.16.

Edmondson D, Richardson S, Falzon L, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder prevalence and risk of recurrence in acute coronary syndrome patients: a meta-analytic review. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e38915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038915.

Roberge MA, Dupuis G, Marchand A. Post-traumatic stress disorder following myocardial infarction: prevalence and risk factors. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26(5):e170–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0828-282x(10)70386-x.

Assayag EB, Tene O, Korczyn AD, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms after stroke: the effects of anatomy and coping style. Stroke. 2022;53(6):1924–33. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.036635.

O’Donnell CJ, Longacre LS, Cohen BE, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease: state of the science, knowledge gaps, and research opportunities. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(10):1207–16. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2530.

von Kanel R, Hari R, Schmid JP, et al. Non-fatal cardiovascular outcome in patients with posttraumatic stress symptoms caused by myocardial infarction. J Cardiol. 2011;58(1):61–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjcc.2011.02.007.

Bryant RA, Moulds ML, Guthrie RM. Acute Stress Disorder Scale: a self-report measure of acute stress disorder. Psychol Assess. 2000;12(1):61–8.

O’Neill S, Brady RR, Kerssen JJ, Park RW. Mortality associated with traumatic injuries in the elderly: a population based study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(3):e426–30.

Vishnevsky T, Cann A, Calhoun LG, et al. Gender differences in self-reported posttraumatic growth: a meta-analysis. Psychol Women Q. 2010;34:110–20.

Vilchinsky N, Ginzburg K, Fait K, et al. Cardiac-disease-induced PTSD (CDI-PTSD): a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;55:92–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.009.

Baetta R, Pontremoli M, Fernandez AM, et al. Reprint of: proteomics in cardiovascular diseases: unveiling sex and gender differences in the era of precision medicine. J Proteom. 2018;178:57–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2018.03.017.

Jawitz OK. Sex disparities in coronary artery bypass techniques: A Society of Thoracic Surgeons database analysis. Presentation to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons; 2021. Retrieved from https://cardiovascularnews.com/sts-2021-study-identifies-significant-gender-disparities-in-cabg/.

Robinson NB, Naik A, Rahouma M, et al. Sex differences in outcomes following coronary artery bypass grafting: a meta-analysis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2021;33(6):841–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivab191.

Kabutoya T, Hoshide S, Davidson KW, et al. Sex differences and the prognosis of depressive and nondepressive patients with cardiovascular risk factors: the Japan Morning Surge-Home blood pressure (J-HOP) study. Hypertens Res. 2018;41(11):965–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-018.

Lam L, Ahn HJ, Okajima K, et al. Gender differences in the rate of 30-day readmissions after percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndrome. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29(1):17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2018.09.002.

Shaw LJ, Min JK, Nasir K, et al. Sex differences in calcified plaque and long-term cardiovascular mortality: observations from the CAC Consortium. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(41):3727–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy534.

Allabadi H, Probst-Hensch N, Alkaiyat A, et al. Mediators of gender effects on depression among cardiovascular disease patients in Palestine. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):284. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2267-4.

Pulver S, Ulibarri N, Sobocinski KL, et al. Frontiers in socio-environmental research: components, connections, scale, and context. Ecol Soc. 2018. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10280-230323.

Tulloch H, Greenman PS, Tasse V. Post-traumatic stress disorder among cardiac patients: prevalence, risk factors, and considerations for assessment and treatment. Behav Sci. 2014;5(1):27–40. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs5010027.

Greenman PS, Viau P, Morin F, et al. Of sound heart and mind: a scoping review of risk and protective factors for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress in people with heart disease. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;33(5):E16–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/jcn.0000000000000508.

Kaplan RM, Hays RD. Health-related quality of life measurement in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2022;5(43):355–73. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052120-012811.

Kurfirst V, Mokracek A, Krupauerova M, et al. Health-related quality of life after cardiac surgery–the effects of age, preoperative conditions and postoperative complications. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;9:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1749-8090-9-46.

Noyez L, de Jager MJ, Markou AL. Quality of life after cardiac surgery: underresearched research. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;13(5):511–4. https://doi.org/10.1510/icvts.2011.276311.

Perrotti A, Ecarnot F, Monaco F, et al. Quality of life 10 years after cardiac surgery in adults: a long-term follow-up study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1160-7.

Piotrowicz K, Noyes K, Lyness JM, et al. Physical functioning and mental well-being in association with health outcome in patients enrolled in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(5):601–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehl485.

Jung HG, Yang YK. Factors influencing health behavior practice in patients with coronary artery diseases. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01635-2.

Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, et al. The will and the ways: development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1991;60(4):570–85.

Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychololgy. 1985;4(3):219–47.

Ai LA, Carretta H. Depression in patients with heart diseases: gender differences and association of comorbidities, optimism, and spiritual struggle. Int J Behav Med. 2021;28:382–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-020-09915-3.

Anthony EG, Kritz-Silverstein D, Barrett-Connor E. Optimism and mortality in older men and women: The Rancho Bernardo Study. J Aging Res. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5185104.

Bouchard LC, Carver CS, Mens MG, et al. Optimism, health, and well-being. In: Dunn DS, et al., editors. Positive psychology: established and emerging issues. New York, NY: Routledge; 2018. p. 112–30.

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Segerstrom SC, Optimism. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(7):879–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006.

Galatzer-Levy IR, Bonanno GA. Optimism and death: predicting the course and consequences of depression trajectories in response to heart attack. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(12):2177–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614551750.

Rasmussen HN, Scheier MF, Greenhouse JB. Optimism and physical health: a meta-analytic review. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37(3):239–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9111-x.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980.

Saunders DG. Posttraumatic stress symptom profiles of battered women: a comparison of survivors in two settings. Violence Vict. 1994;9(1):31–44.

Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The rand 36-item health survey 1.0. Health Econ. 1993;2(3):217–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4730020305.

Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, et al. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Personal Assess. 1990;55(3–4):610–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095.

Tessler J, Bordoni B. Cardiac rehabilitation. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

Balasubramanian BA, Cohen DJ, et al. Outcomes of integrated behavioral health with primary care. J Am Board Family Med. 2017;30(2):130–9. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2017.02.160234.

Herrmann-Lingen C, Albus C, de Zwaan M, et al. Efficacy of team-based collaborative care for distressed patients in secondary prevention of chronic coronary heart disease (TEACH): study protocol of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20(1):520. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01810-9.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Amy Ai had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The opinions expressed in this study do not represent those of the founders.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R03 AG015686-01, R03 AG060212-01A1) to Amy L. Ai, PhD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Institutional Review Board approvals were received from the previous NIA grant–funded data collection. Approval for secondary analysis of the resulting data was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Florida State University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ai, A.L., Appel, H.B. & Lin, C.J. Sex and Psychosocial Differences in Acute Stress Symptoms Prior to Open-Heart Surgery. Int.J. Behav. Med. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-024-10287-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-024-10287-1