Abstract

Background

Skin cancer incidence and prognosis vary by ethnicity and gender, and previous studies demonstrate ethnic and gender differences in sun-related cognitions and behaviors that contribute to this disease. The current study sought to inform skin cancer interventions tailored to specific demographic groups of college students. The study applied the prototype willingness model (PWM) to examine how unique combinations of ethnic and gender identities influence sun-related cognitions.

Method

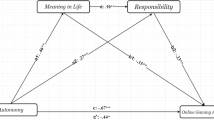

Using data from a survey of 262 college students, the study tested whether self-reported sun-related cognitions were different for White women, Hispanic women, White men, and Hispanic men. Path modeling was also used to identify which PWM cognitions (e.g., prototypes, norms) were the strongest predictors of risk and protection intentions and willingness in each demographic group.

Results

Several differences in sun-related cognitions and PWM pathways emerged across groups, emphasizing the need for tailored skin cancer education and interventions. Results suggest that, for White women, interventions should primarily focus on creating less favorable attitudes toward being tan.

Conclusion

Interventions for Hispanic women may instead benefit from manipulating perceived similarity to sun-related prototypes, encouraging closer personal identification with images of women who protect their skin and encouraging less identification with images of women who tan. For White men, skin cancer interventions may focus on creating more favorable images of men who protect their skin from the sun. Lastly, interventions for Hispanic men should increase perceived vulnerability for skin cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available at Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/SNKCY.

References

American Academy of Dermatology Association. Skin Cancer. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-skin-cancer. Accessed 12 Dec 2020.

National Cancer Institute: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. SEER*Explorer: Explore Our Statistics. https://seer.cancer.gov/explorer/. Accessed 12 Dec 2020.

Perez MI. Skin cancer in Hispanics in the United States. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(3):s117-120.

Loh TY, Ortiz A, Goldenberg A, Jiang SIB. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of nonmelanoma skin cancers among Hispanic and Asian patients compared with white patients in the United States: a 5-year, single-institution retrospective review. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(5):639–45.

Higgins S, Nazemi A, Chow M, Wysong A. Review of nonmelanoma skin cancer in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2019;44(7):903–10.

Holman DM, Ding H, Guy GP Jr, Watson M, Hartman AM, Perna FM. Prevalence of sun protection use and sunburn and association of demographic and behavioral characteristics with sunburn among US adults. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(5):561–8.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Surgeon general call to action to prevent skin cancer: exec summary. https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/skin-cancer/executive-summary/index.html. Accessed 12 Dec 2020.

Buller DB, Cokkinides V, Hall HI, et al. Prevalence of sunburn, sun protection, and indoor tanning behaviors among Americans: review from national surveys and case studies of 3 states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5):S114–23.

Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Stock ML, Finneran SD. The prototype/willingness model. In: Connor M, Norman P, editors. Predicting and Changing Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2015. p. 189–216.

Holman DM, Watson M. Correlates of intentional tanning among adolescents in the United States: a systematic review of the literature. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(5):S52–9.

Pettijohn TF II, Pettijohn TF, Gilbert AG. Romantic relationship status and gender differences in sun tanning attitudes and behaviors of US college students. Psychol. 2011;2(2):71.

Holman DM, Berkowitz Z, Guy GP Jr, Hawkins NA, Saraiya M, Watson M. Patterns of sunscreen use on the face and other exposed skin among US adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(1):83–92.

Falk M, Anderson CD. Influence of age, gender, educational level and self-estimation of skin type on sun exposure habits and readiness to increase sun protection. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37(2):127–32.

Dwyer L, Stock ML. UV photography, masculinity, and college men’s sun protection cognitions. J Behav Med. 2011;35(4):431–2.

McKenzie C, Rademaker AW, Kundu RV. Masculine norms and sunscreen use among adult men in the United States: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):243–4.

Calderón TA, Bleakley A, Jordan AB, Lazovich D, Glanz K. Correlates of sun protection behaviors in racially and ethnically diverse US adults. Prev Med Rep. 2018;13:346–53.

Weiss J, Kirsner RS, Hu S. Trends in primary skin cancer prevention among US Hispanics: a systematic review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(5):580–6.

Cheng CE, Irwin B, Mauriello D, Hemminger L, Pappert A, Kimball AB. Health disparities among different ethnic and racial middle and high school students in sun exposure beliefs and knowledge. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(1):106–9.

Fogel J, Krausz F. Watching reality television beauty shows is associated with tanning lamp use and outdoor tanning among college students. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(5):784–9.

Lunsford NB, Berktold J, Holman DM, Stein K, Prempeh A, Yerkes A. Skin cancer knowledge, awareness, beliefs and preventive behaviors among Black and Hispanic men and women. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:203–9.

Viola AS, Stapleton JL, Coups EJ. Associations between linguistic acculturation and skin cancer knowledge and beliefs among US Hispanic adults. Prev Med Rep. 2019;15:100943.

Thoonen K, Schneider F, Candel M, de Vries H, van Osch L. Childhood sun safety at different ages: relations between parental sun protection behavior towards their child and children’s own sun protection behavior. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1044.

Bandi P, Cokkinides VE, Weinstock MA, Ward EM. Physician sun protection counseling: prevalence, correlates, and association with sun protection practices among US adolescents and their parents, 2004. Prev Med. 2010;51(2):172–7.

Carcioppolo N, Orrego Dunleavy V, Myrick JG. A closer look at descriptive norms and indoor tanning: investigating the intermediary role of positive and negative outcome expectations. Health Commun. 2019;34(13):1619–27.

Coups EJ, Stapleton JL, Hudson SV, Medina-Forrester A, Natale-Pereira N, Goydos JS. Sun protection and exposure behaviors among Hispanic adults in the United States: differences according to acculturation and among Hispanic subgroups. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):985.

Lewis MA, Litt DM, King KM, et al. Examining the ecological validity of the prototype willingness model for adolescent and young adult alcohol use. Psychol Addict Behav. 2019;34(2):293–302.

Molloy BK, Stock ML, Dodge T, Aspelund JG. Predicting future academic willingness, intentions, and nonmedical prescription stimulant (NPS) use with the theory of reasoned action and prototype/willingness model. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54(14):2251–63.

Todd J, Kothe E, Mullan B, Monds L. Reasoned versus reactive prediction of behaviour: a meta-analysis of the prototype willingness model. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(1):1–24.

Matterne U, Diepgen TL, Weisshaar E. A longitudinal application of three health behaviour models in the context of skin protection behaviour in individuals with occupational skin disease. Psychol Health. 2011;26(9):1188–207.

Walsh LA, Stock ML. UV photography, masculinity, and college men’s sun protection cognitions. J Behav Med. 2012;35(4):431–42.

Stock ML, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, et al. Sun protection intervention for highway workers: long-term efficacy of UV photography and skin cancer information on men’s protective cognitions and behavior. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(3):225–36.

Howell JL, Ratliff KA. Investigating the role of implicit prototypes in the prototype willingness model. J Behav Med. 2017;40(3):468–82.

Mahler HIM, Kulik JA, Harrell J, Correa A, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Effects of UV photographs, photoaging information, and use of sunless tanning lotion on sun protection behaviors. JAMA Dermatol. 2005;141(3):373–80.

Morris K, Swinbourn A. Identifying prototypes associated with sun-related behaviours in North Queensland. Aus J Psy. 2014;66(4):216–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12052.

Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124(6):869–71.

Bodimeade H, Anderson E, La Macchia S, et al. Testing the direct, indirect, and interactive roles of referent group injunctive and descriptive norms for sun protection in relation to the theory of planned behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2014;44(11):739–50.

Mahler HI, Kulik JA, Butler HA, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX. Social norms information enhances the efficacy of an appearance-based sun protection intervention. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(2):321–9.

Dennis LK, Lowe JB, Snetselaar LG. Tanning behavior among young frequent tanners is related to attitudes and not lack of knowledge about the dangers. Health Educ J. 2009;68(3):232–43.

Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Reis-Bergan M, Trudeau L, Vande Lune LS, Buunk B. Inhibitory effects of drinker and nondrinker prototypes on adolescent alcohol consumption. Health Psychol. 2016;21(6):601–9.

Litt DM, Lewis MA. Examining the role of abstainer prototype favorability as a mediator of the abstainer norms-drinking behavior relationship. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29(2):467–72.

Ratliff KA, Howell JL. Implicit prototypes predict risky sun behavior. Health Psychol. 2016;34(3):231–42.

Cornelis E, Cauberghe V, De Pelsmacker P. Being healthy or looking good? The effectiveness of health versus appearance-focused arguments in two-sided messages. J Health Psychol. 2014;19(9):1132–42.

Gibbons FX, Houlihan AE, Gerrard M. Reason and reaction: the utility of a dual-focus, dual-processing perspective on promotion and prevention of adolescent health risk behavior. Br J Health Psychol. 2009;24:231–48.

Litt DM, Lewis MA, Fairlie AM, Head-Corliss MK. An examination of the relative associations of prototype favorability, similarity, and their interaction with alcohol and alcohol-related risky sexual cognitions and behavior. Emerg Adulthood. 2020;8(2):168–74.

Rivis A, Sheeran P, Armitage CJ. Augmenting the theory of planned behaviour with the prototype/willingness model: predictive validity of actor versus abstainer prototypes for adolescents’ health-protective and health-risk intentions. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11(3):483–500.

Jackson KM, Aiken LS. Evaluation of a multicomponent appearance-based sun-protective intervention for young women: uncovering the mechanisms of program efficacy. Health Psychol. 2006;25(1):34.

Stapleton JL, Manne SL, Darabos K, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a web-based indoor tanning intervention: acceptability and preliminary outcomes. Health Psychol. 2015;34S:1278–85.

Coups EJ, Stapleton JL, Manne SL, et al. Psychosocial correlates of sun protection behaviors among US Hispanic adults. J Behav Med. 2014;37(6):1082–90.

Coups EJ, Stapleton JL, Hudson SV, et al. Skin cancer surveillance behaviors among US Hispanic adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(4):576–84.

Andreeva VA, Unger JB, Yaroch AL, Cockburn MG, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Reynolds KD. Acculturation and sun-safe behaviors among US Latinos: findings from the 2005 Health Information National Trends Survey. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):734–41.

Chen H-Y, Jablonski NG. Stay out of the sun: exploring African American college women’s thoughts on the dynamics between colorism and sun-related behavior. J Black Psychol. 2022.

Chen H-Y, Robinson JK, Jablonski NG. A cross-cultural exploration on the psychological aspects of skin color aesthetics: implications for sun-related behavior. Trans Beh Med. 2020;10(1):234–43.

Chen H-Y, Yarnal C, Chick G, Jablonski N. Egg white or sun-kissed: a cross-cultural exploration of skin color and women’s leisure behavior. Sex Roles. 2018;78(3–4):255–71.

Noe-Bustamante L, Gonzalez-Barrera A, Edwards K, Mora L, Lopez MH. Majority of Latinos say skin color impacts opportunity in america and shapes daily life. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2021/11/04/majority-of-latinos-say-skin-color-impacts-opportunity-in-america-and-shapes-daily-life/. Accessed 16 Sept 2022.

Lane DJ, Gibbons FX, O’Hara RE, Gerrard M. Standing out from the crowd: how comparison to prototypes can decrease health-risk behavior in young adults. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2011;33(3):228–38.

Chait SR, Thompson JK, Jacobsen PB. Preliminary development and evaluation of an appearance-based dissonance induction intervention for reducing UV exposure. Body Image. 2015;12:68–72.

Williams AL, Grogan S, Clark-Carter D, Buckley E. Appearance-based interventions to reduce ultraviolet exposure and/or increase sun protection intentions and behaviours: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18(1):182–217.

Rodríguez VM, Shuk E, Arniella G, et al. A qualitative exploration of Latinos’ perceptions about skin cancer: the role of gender and linguistic acculturation. J Cancer Educ. 2017;32(3):438–46.

Werch CEC, Bian H, DiClemente CC, et al. A brief image-based prevention intervention for adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24(1):170–5.

Hagerman CJ, Stock ML, Molloy BK, Beekman JB, Klein WMP, Butler N. Combining a UV photo intervention with self-affirmation or self-compassion exercises: implications for skin protection. J Behav Med. 2019;43(5):743–53.

Mahler HIM. The relative role of cognitive and emotional reactions in mediating the effects of a social comparison sun protection intervention. Psychol Health. 2018;33(2):235–57.

Day AK, Wilson CJ, Hutchinson AD, Roberts RM. Sun-related behaviours among young Australians with Asian ethnic background: differences according to sociocultural norms and skin tone perceptions. Eur J Cancer. 2014;24:514–21.

Laursen B, Faur S. What does it mean to be susceptible to influence? A brief primer on peer conformity and developmental changes that affect it. Int J Behav Dev. 2022;46(3):222–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/01650254221084103.

Raymond-Lezman JR, Riskin S. Attitudes, behaviors, and risks of sun protection to prevent skin cancer amongst children, adolescents, and adults. Cureus. 2023;15(2):e34934.

Daniel LC, Heckman CJ, Kloss JD, Manne SL. Comparing alternative methods of measuring skin color and damage. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(3):313–21.

Falk M. Self-estimation or phototest measurement of skin UV sensitivity and its association with people’s attitudes towards sun exposure. Antican Res. 2014;34(2):797–803. https://ar.iiarjournals.org/content/34/2/797.

Widemar K, Falk M. Sun exposure and protection index (SEPI) and self-estimated sun sensitivity. J Prim Prev. 2018;39(5):437–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/2Fs10935-018-0520-0.

Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818401100101.

Gwon SH, Jeong S. Concept analysis of impressionability among adolescents and young adults. Nurs Open. 2018;5:1–10.

Ditre JW, LaRowe LR, Powers JM, et al. Pain as a causal motivator of alcohol consumption: associations with gender and race. J Psychopathol Clin Sci. 2022;132(1):101–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000792.

NIH Office of Extramural Research. Designing analyses of sex or gender, race, and ethnicity in NIH-defined Phase 3 clinical trials. https://nexus.od.nih.gov/all/2022/03/10/designing-analyses-by-sex-or-gender-race-and-ethnicity-in-nih-defined-phase-3-clinical-trials/. Accessed 15 Sept 2023.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship awarded to L.D. (Grant No. DGE-1246908).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Additionally the study was approved by the George Washington University Institutional Review Board (IRB #111216) and the Texas A&M University Corpus Christi Institutional Review Board (IRB #162-12).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study prior to starting the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

Dr. Dwyer is a Scientific Program Manager (Contractor) with Cape Fox Facilities Services at the Behavioral Research Program, National Cancer Institute. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views or policies of the US National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, or Department of Health and Human Services.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hagerman, C.J., Stock, M.L., Jobe, M.C. et al. Ethnic and Gender Differences in Sun-Related Cognitions Among College Students: Implications for Intervention. Int.J. Behav. Med. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-024-10257-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-024-10257-7