Abstract

Background

The Common Sense Model provides a framework to understand health beliefs and behaviors. It includes illness representations comprised of five domains (identity, cause, consequences, timeline, and control/cure). While widely used, it is rarely applied to obesity, yet could explain self-management decisions and inform treatments. This study answered the question, what are patients’ illness representations of obesity?; and examined the Common Sense Model’s utility in the context of obesity.

Methods

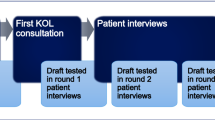

Twenty-four participants with obesity completed semi-structured phone interviews (12 women, 12 men). Directed content analysis of transcripts/notes was used to understand obesity illness representations across the five illness domains. Potential differences by gender and race/ethnicity were assessed.

Results

Participants did not use clinical terms to discuss weight. Participants’ experiences across domains were interconnected. Most described interacting life systems as causing weight problems and used negative consequences of obesity to identify it as a health threat. The control/cure of obesity was discussed within every domain. Participants focused on health and appearance consequences (the former most salient to older, the latter most salient to younger adults). Weight-related timelines were generally chronic. Women more often described negative illness representations and episodic causes (e.g., pregnancy). No patterns were identified by race/ethnicity.

Conclusions

The Common Sense Model is useful in the context of obesity. Obesity illness representations highlighted complex causes and consequences of obesity and its management. To improve weight-related care, researchers and clinicians should focus on these beliefs in relation to preferred labels for obesity, obesity’s most salient consequences, and ways of monitoring change.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, Hu FB, Hubbard VS, Jakicic JM, Kushner RF, Loria CM. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Jul 1;63(25 Part B):2985-3023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004

Breland JY, Frayne SM, Timko C, Washington DL, Maguen S. Mental health and obesity among veterans: a possible need for integrated care. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(5):506–9.

Flint SW, Oliver EJ, Copeland RJ. Editorial: obesity stigma in healthcare: impacts on policy, practice, and patients. Front Psychol. 2017;8(2149). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02149

Semlitsch T, Stigler FL, Jeitler K, Horvath K, Siebenhofer A. Management of overweight and obesity in primary care-a systematic overview of international evidence-based guidelines. Obes Rev. 2019;20(9):1218–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12889.

Puhl R, Suh Y. Health consequences of weight stigma: implications for obesity prevention and treatment. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4(2):182–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-015-0153-z.

Puhl RM, Phelan SM, Nadglowski J, Kyle TK. Overcoming weight bias in the management of patients with diabetes and obesity. Clin Diabetes. 2016;34(1):44–50. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaclin.34.1.44.

Andrew J, Friedman M, editors. Body stories: in and out and with and through fat. Bradford, Ontario, Canada: Demeter Press; 2020.

Littman AJ, Damschroder LJ, Verchinina L, et al. National evaluation of obesity screening and treatment among veterans with and without mental health disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(1):7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.11.005.

De Brun A, McCarthy M, McKenzie K, McGloin A. Examining the media portrayal of obesity through the lens of the Common Sense Model of illness representations. Health Commun. 2015;30(5):430–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2013.866390.

Breland JY, Fox AM, Horowitz CR, Leventhal H. Applying a common-sense approach to fighting obesity. J Obes. 2012;2012: 710427. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/710427.

Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Breland JY. Cognitive science speaks to the “common-sense” of chronic illness management. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(2):152–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9246-9.

Leventhal H, Phillips LA, Burns E. The Common-Sense Model of self-regulation (CSM): a dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. J Behav Med. 2016;39(6):935–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9782-2.

Hagger MS, Koch S, Chatzisarantis NLD, Orbell S. The common sense model of self-regulation: meta-analysis and test of a process model. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(11):1117–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000118.

Hagger MS, Orbell S. A meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representations. Psychol Health. 2003;18(2):141–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/088704403100081321.

Kaptein AA, Hughes BM, Scharloo M, et al. Illness perceptions about asthma are determinants of outcome. J Asthma. 2008;45(6):459–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770900802040043.

Broadbent E, Donkin L, Stroh JC. Illness and treatment perceptions are associated with adherence to medications, diet, and exercise in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):338–40. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-1779.

Breland JY, McAndrew LM, Gross RL, Leventhal H, Horowitz CR. Challenges to healthy eating for people with diabetes in a low-income, minority neighborhood. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(10):2895–901. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-1632.

Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(6):631–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020.

Phillips LA, Leventhal H, Burns EA. Choose (and use) your tools wisely: “validated” measures and advanced analyses can provide invalid evidence for/against a theory. J Behav Med. 2017;40(2):373–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9807-x.

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y.

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82.

Frayne SM, Carney DV, Bastian L, et al. The VA women’s health practice-based research network: amplifying women veterans’ voices in VA research. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(Suppl 2):S504–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2476-3.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(6):855–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973230201200611.

Baumann LJ, Leventhal H. I can tell when my blood pressure is up, can’t I? Health Psychol. 1985;4(3):203–18.

Kyle TK, Dhurandhar EJ, Allison DB. Regarding obesity as a disease: evolving policies and their implications. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2016;45(3):511–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2016.04.004.

Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):715–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12551

Breland JY, Donalson R, Dinh JV, Maguen S. Trauma exposure and disordered eating: a qualitative study. Women Health. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2017.1282398.

Puhl RM, Himmelstein MS, Quinn DM. Internalizing weight stigma: prevalence and sociodemographic considerations in US adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26(1):167–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22029.

Breland JY, Patel ML, Wong JJ, Hoggatt KJ. Weight perceptions and weight loss attempts: military service matters. Mil Med. 2020;185(3–4):e397–402. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usz413.

Jylha M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(3):307–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013.

Bokhour BG, Haun JN, Hyde J, Charns M, Kligler B. Transforming the veterans affairs to a whole health system of care: time for action and research. Med Care. 2020;58(4):295–300. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001316.

Eibner C, Krull H, Brown KM, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique health care needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Coporation. 2015.

Drabble L, Trocki KF, Salcedo B, Walker PC, Korcha RA. Conducting qualitative interviews by telephone: lessons learned from a study of alcohol use among sexual minority and heterosexual women. Qualitative social work: QSW: research and practice. 2016;15(1):118–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325015585613.

Acknowledgements

The views represented herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D) Career Development Award (CDA 15–257, Dr. Breland) at the VA Palo Alto, a Senior Research Career Scientist award (RCS 00–001, Dr. Timko), and the VA HSR&D Center of Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN 13–413, Dr. Dawson). Dr. Dawson was partly supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, Department of Veterans Affairs; and by the South Central Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Breland, J.Y., Dawson, D.B., Puran, D. et al. Common Sense Models of Obesity: a Qualitative Investigation of Illness Representations. Int.J. Behav. Med. 30, 190–198 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-022-10082-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-022-10082-w