Abstract

Background

Poor balance between work and family can be a major stressor for women with young children and have a negative impact on emotional well-being. Family-friendly workplace attributes may reduce stress and depressive symptoms among this population. However, few studies have analyzed the role of specific workplace attributes on mental health outcomes among women with young children because available data are limited.

Purpose

This study examines the impact of workplace attributes on changes in depressive symptoms among working women with young children between 6 and 24 months of age.

Method

This study uses data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD) collected between 1991 and 1993 to examine the effects of work intensity, work schedule (night/day/variable), schedule flexibility, working from home, and work stress on changes in depressive symptoms among a national US sample of 570 women who returned to work within 6 months after childbirth. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the CES-D score. Treatment effects were estimated using fixed effects regression models.

Results

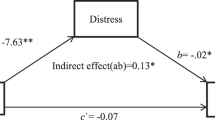

Working from home and work stress predicted within-individual changes in depressive symptoms between 6 and 24 months postchildbirth. Women who worked from home reported a statistically significant decrease in depression scores over time (β = −1.36, SE = 0.51, p = 0.002). Women who reported a one-unit increase in job concerns experienced, on average, a 2-point increase in depression scores over time (β = 1.73, SE = 0.37, p < 0.01). Work intensity, work schedule, and schedule flexibility were not associated with changes in depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

This study is one of the few to use longitudinal data and causal-inference techniques to examine whether specific workplace attributes influence depressive symptoms among women with young children. Reducing stress in the workplace and allowing women to work from home may improve mental health among women who transition back to work soon after childbirth.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dye JL. Fertility of American Women. Curr Popul Reports. 2005;20-555.

Shepherd-Banigan M, Bell J. Paid leave benefits of working mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(1):286–95.

Killien MG, Habermann B, Jarrett M. Influence of employment characteristics on postpartum mothers’ health. Women Health. 2001;33(1–2):63–81. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11523641.

Chen CH. Association of work status and mental well-being in new mothers. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2001;17(11):570–5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11852464.

Mayberry LJ, Horowitz JA, Declercq E. Depression symptom prevalence and demographic risk factors among U.S. women during the first 2 years postpartum. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(6):542–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17973697.

Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Sasaki S, Hirota Y. Employment, income, and education and risk of postpartum depression: the Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1–2):133–7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21055825.

Stansfeld S, Candy B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health–a meta-analytic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(6):443–62. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17173201.

Nichols MR, Roux GM. Maternal perspectives on postpartum return to the workplace. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004;33(4):463–71. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15346672.

Strazdins L, Shipley M, Broom D. What does family-friendly really mean? Well being, time and quality of parents’ jobs. Aust Bull Labor. 2007.

Grice MM, Feda D, McGovern P, Alexander BH, McCaffrey D, Ukestad L. Giving birth and returning to work: the impact of work-family conflict on women’s health after childbirth. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(10):791–8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17719242.

Grice MM, McGovern PM, Alexander BH, Ukestad L, Hellerstedt W. Balancing work and family after childbirth: a longitudinal analysis. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(1):19–27. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21185988.

Friedman DE. Employer supports for parents with young children. Future Child. 2001;11(1):62–77. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11712457.

Frye NK, Breaugh JA. Family-friendly policies, supervisor support, work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and satisfaction: a test of a conceptual model. J Bus Psychol. 2004;19(2):197–220. doi:10.1007/s10869-004-0548-4.

Allen TD. Family-supportive work environments: the role of organizational perceptions. J Vocat Behav. 2001;58(3):414–35. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2000.1774.

Carlson DS, Grzywacz JG, Ferguson M, Hunter EM, Clinch CR, Arcury TA. Health and turnover of working mothers after childbirth via the work-family interface: an analysis across time. J Appl Psychol. 2011;96(5):1045–54. doi:10.1037/a0023964.

Joyce K, Pabayo R, Critchley JA, Bambra C. Flexible working conditions and their effects on employee health and wellbeing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2:CD008009. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008009.pub2.

Dagher RK, McGovern PM, Alexander BH, Dowd BE, Ukestad LK, McCaffrey DJ. The psychosocial work environment and maternal postpartum depression. Int J Behav Med. 2009;16(4):339–46. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19288209. Accessed July 25, 2012.

Dagher RK, McGovern PM, Dowd BE, Lundberg U. Postpartum depressive symptoms and the combined load of paid and unpaid work: a longitudinal analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2011;84(7):735–43. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21373878.

Staines GL, Pleck JH. Nonstandard work schedules and family life. J Appl Psychol. 1984;69(3):515–23. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.69.3.515.

Kolla BP, Auger RR. Jet lag and shift work sleep disorders: how to help reset the internal clock. Cleve Clin J Med. 2011;78(10):675–84. doi:10.3949/ccjm.78a.10083.

Lindberg L. Women’s decisions about breasteeding and maternal employment. J Marriage Fam. 1996;58:239–51.

Johnston ML, Esposito N. Barriers and facilitators for breastfeeding among working women in the United States. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(1):9–20. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00109.x.

Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, Mullan JT. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22(4):337–56. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7320473.

McGovern P, Dowd B, Gjerdingen D, et al. Mothers’ health and work-related factors at 11 weeks postpartum. Ann Fam Med. 2006;5(6):519–27. doi:10.1370/afm.519.

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Nonmaternal care and family factors in early development: an overview of the NICHD study of early child care. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2001;22:457–92.

Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff BA, Locke BZ. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;106(3):203–14. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/900119.

Davis J. School enrollment and work status: 2011. Washington, DC; 2012.

Marshall NL, Barnett RC. Work-family strains and gains among two-earner couples. J Community Psychol. 1993;21(1):64–78. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(199301)21:1<64::AID-JCOP2290210108>3.0.CO;2-P.

Barnett RC, Davidson H, Marshall NL. Physical symptoms and the interplay of work and family roles. Health Psychol. 1991;10(2):94–101. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2055215.

Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nurs Res. 2001;50(5):275–85. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11570712.

Pearl J. Causal inference in statistics: an overview. Stat Surv. 2009;3:96–146. doi:10.1214/09-SS057.

Shadish W, TD C, Campbell D. Experimental and quasi-experiemental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mufflin; 2001.

Dowd B, Town R. Does X Really Cause Y?. Washington, DC; 2002. http://www.academyhealth.org/files/FileDownloads/DoesXCauseY.pdf.

Cameron A, Trivedi P. Microeconomics Using STATA. Revised. College Station: STATA Press; 2010.

Population Esimates Program PD. Resident Population Estimates of the United States by Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: April 1, 1990 to July 1, 1999 with Short-Term Projection to November 1, 2000. Washington, DC; 2001. http://www.census.gov/popest/data/national/totals/1990s/tables/nat-srh.txt.

US Census Bureau. Mediam Income for 4-Person Families, by State. Washington, DC; 2013. https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/statistics/4person.html.

BLS Reports. Women in the labor force: a databook. Washington, DC; 2013. http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-databook-2012.pdf.

Cooklin AR, Rowe HJ, Fisher JRW. Employee entitlements during pregnancy and maternal psychological well-being. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47(6):483–90. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00784.x.

Allvin M, Aronsson G, Hagstrom T, Johannson G, Lundberg U. Work without boundaries: psychological perspectives on the new working life. Wiley; 2011. http://au.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-0470666137.html.

United States Census Bureau. America’s changing labor force: equal employment opportunity tabulation.; 2013. http://www.census.gov/people/eeotabulation/.

Berger LM, Hill J, Waldfogel J. Maternity leave, early maternal employment and child health and development in the US. Econ J. 2005;115(501):F29–47. doi:10.1111/j.0013-0133.2005.00971.x.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. American Time Use Survey-2013 Results.; 2014. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/atus.nr0.htm.

Christensen K, Schneider B, Butler D. Families with school-age children. Future Child. 2011;21(2):69–90. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22013629.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Grant Number 1 T42 OH008433 from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (OSHA) and Grant Number TL1 TR0042 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

Informed Consent

This study was deemed to be exempt from institutional review by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of Interest

Authors Shepherd-Banigan, Bell, Basu, Booth-LaForce, and Harris declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shepherd-Banigan, M., Bell, J.F., Basu, A. et al. Workplace Stress and Working from Home Influence Depressive Symptoms Among Employed Women with Young Children. Int.J. Behav. Med. 23, 102–111 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-015-9482-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-015-9482-2