Abstract

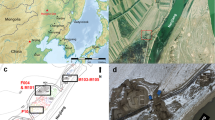

Disposal of victims’ bodies in existing tombs or graveyards is a strategy not uncommon in modern homicide cases. In this study, we report a young male homicide victim dated 1300 years ago (during the Tang Dynasty) found in a shaft made by the robbers of a 2000-year-old tomb (East Han Dynasty), located in the Shiyanzi cemetery of Ningxia, China. The skeleton of the victim was nearly complete, found in a slumped posture inside the half-filled shaft from the grave robbers. There were multiple sharp-force marks on his skeleton, including more severe traumata to the facial skeleton and the thoracic elements. Through a reconstruction of the tomb and its relationship with the individual, it was believed that this individual was a victim of an assault. After the assault, the victim was dumped in this shaft to purposely kept from sight. The case indicates that the strategy of hiding victims’ bodies in existing tombs or graveyards as a means of disposal, akin to “hiding a leaf in the forest,” has been practiced since antiquity. This millennium-old case enriches the long history of homicide behaviors, such as the returning of senses to the perpetrator/s after violent actions to hide evidence and avoid punishment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability statement

Research data and images will be available in the public domain after the completion and publication of the findings. Entities include Jilin University and Texas A&M University.

References

Buikstra JE, Ubelaker D (1994) Standards for data collection from human skeletal remains. Fayetteville, Arkansas: Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series, No 44

Congram D (2014) Deposition and dispersal of human remains as a result of criminal acts: Homo sapiens sapiens as a Taphonomic Agent. In: Pokines JT, Symes SA (eds) Manual of forensic taphonomy. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 249–285

Fengxi Archaeological Team IA, CASS (1988) 1984 nian chang an pu du cun xi zhou mu zang fa jue jian bao[Brief report on excavation of Western Zhou Dynasty burials from Pudu Village in Chang’an, 1984](in Chinese). Archaeology 9:769-777+799+865

Horowitz A (2017) The word is murder: a novel. Harper Collins publisher, New York City

Jordana X, Galtés I, Turbat T, Batsukh D, García C, Isidro A, Giscard PH, Malgosa A (2009) The warriors of the steppes: osteological evidence of warfare and violence from Pazyryk tumuli in the Mongolian Altai. J Archaeol Sci 36(7):1319–1327

Kjellström A (2005) A sixteenth–century warrior grave from Uppsala, Sweden: the Battle of Good Friday. Int J Osteoarchaeol 15:23–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.746

Lin HK, Yue LX (2020) Ethical reflections on the behavior of grave robbers: an investigation of the tomb relics from Han and Tang Dynasty Brick–and–stone tombs along the Hexi Corridor (in Chinese). J Orig Ecol Natl Cult 12(02):139–144

Liu XL (2011) Tang lü “qi sha” yan jiu[The research on seven traditional Chinese homicides of Tang Dynasty laws] (in Chinese). Dissertation. Jilin University

Liu ZZ (2020) Double Space and Three–dimensional World of Han Dynasty Tombs (in Chinese). Nankai J (Philos Lit Soc Sci Ed) 1:108–116

Milner GR (2005) Nineteenth-Century arrow wounds and perceptions of prehistoric warfare. Am Antiq 70:144–156

Moraitis K, Spiliopoulou C (2006) Identification and differential diagnosis of perimortem blunt force trauma in tubular long bones. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 2(4):221–229

Ni FL (2011a) Min guo dao mu shi: nei mu juan [History of tomb raiding in the Republic of China: inside story] (in Chinese). The Chinese Overseas Publishing House, Beijing

Ni FL (2011b) Min guo dao mu shi: mi shu juan [History of tomb raiding in the Republic of China: secret skill] (in Chinese). The Chinese Overseas Publishing House, Beijing

Ningxia Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology (2018) Ning xia hai yuan shi ya zi han mu fa jue jian bao [Brief report on excavation of Hans Dynasty burials from Shiyanzi Cemetery in Haiyuan, Ningxia] (in Chinese). Relics Museol 4:3–16

Ruffell A (2005) Searching for the IRA “disappeared”: ground–penetrating radar investigation of a churchyard burial site, Northern Ireland. J Forensic Sci 50(6):1430–1435

Sauer NJ (1998) The Timing of injuries and manner of death: distinguishing among antemortem, perimortem and postmortem trauma. In: Reichs KJ (ed) Forensic osteology. Advances in the identification of human remains, 2nd edn. Charles C Thomas, Springfield, pp 321–332

Shaanxi Cultural Relics Administration Committee (1964) Tang yong tai gong zhu mu fa jue jian bao [Brief report on excavation of Tomb of Princess Yongtai from Tang Dynasty] (in Chinese). Cult Relics 1:7-33+58–63

Shandong Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Qingzhou City Museum (2014) Shan dong qing zhou xi xing zhan guo mu fa jue jian bao [Brief report on excavation of Warring States Period tomb from in Xixin Qingzhou, Shandong] (in Chinese). Cult Relics 9:4-32+1

Shao XQ (1985) Anthropometric Manual (in Chinese). Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House, Shanghai

Ubelaker DH (1997) Taphonomic applications in forensic anthropplogy. In: Haglund WD, Sorg MH (eds) Forensic taphonomy: the postmortem fate of human remains. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 77–90

Ubelaker DH, Montaperto KM (2014) Trauma interpretation in the context of biological anthropology. In: Knüsel C, Smith MJ (eds) The Routledge handbook of the bioarchaeology of human conflict. Taylor & Francis, Oxfordshire, pp 25–38

Viva S, Lonoce N, Vincenti G, Cameriere R, Valentino M, Vassallo S, Fabbri PF (2020) The mass burials from the western necropolis of the Greek colony of Himera (Sicily) related to the battles of 480 and 409 BCE. Int J Osteoarchaeol 30(3):307–317

Wang Z (2011) Zhong guo dao mu shi [History of grave robbery in China] (in Chinese). Jiuzhou Press, Beijing

Wang Y (2013) Stories of grave robbery (盗墓秘闻). Printing Industry Press, Beijing

Wang K (2014) Tang lü Sha ren zui yan jiu [Research on homicides of Tang Dynasty laws] (in Chinese). Dissertation, Nanjing Normal University

White T, Folkens P (2005) The human bone manual. Elsevier Academic Press, London

Xia Y (1984) Tang lü zhong de mou sha zui [Homicides in Tang Dynasty laws] (in Chinese). Chin J Law 6:66–69

Yang F (2011) Cong kao gu zi liao kan han dai ning xia she hui jing ji fa zhan zhuang kuang [A perspective from archaeological discoveries: the social and economic development of Ningxia in Han Dynasty] (in Chinese). J Yunnan Univ Financ Econ 27(06):149–154

Zhang Q, Wang X, Ye H, Zhang Q (2020) Paleopathological study on the skeleton with cranial lesion from the Shiyanzi Cemetery in Ningxia. Acta Anthropol Sin 39:586–598

Acknowledgements

We thank the Ningxia Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology for their support. Q.W. was supported by the T3 grant from Texas A&M University. Ms. Meghann Holt is thanked for editing the English. We are also grateful to Dr. Li Sun for help and support of various kinds. Drs. Ken Pritzker, Bruce Rothschild, and Matthew Kessler are thanked for helping with differential diagnosis of the lesion on the skull of the original male occupant of the tomb. The editor and reviewers are also thanked for their constructive comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zining Zou and Xiaoyang Wang are joint first authors who contributed equally to this paper.

Appendix

Appendix

Remains of three individuals buried in the M12 tomb, including a 35–40–year–old male, a 30–year–old female, and a child of about 7–8 years old. (a) Remains of a child and a female in the burial chamber in situ. (b) Remains of the male in situ. The skeletons scattered in the burial chambers, presumably by the grave robbers; the layer of the male skeleton was slightly higher than that of skeletons of the female and the juvenile. (c) The skeleton of the male owner for the M12 tomb. (d) The skeleton of the female owner for the M12 tomb. It is noteworthy that there is a lesion in the skull of the male: a circumscribed solitary large lesion, which crosses the midline. There is new bone formation within all three layers of skull with signs yet limited exophytic extension outwards or inwards. Differential diagnosis include osteoblastoma (possible), chronic osteomyelitis (less likely as lesion appears uniform), secondary neoplasm (unlikely as lesion appears uniform and lacks significant exophytic extension. But see Zhang et al. 2020). Hemangiosarcoma, bizarre leukemia, and lymphoma are possible differential diagnosis too

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zou, Z., Wang, X., Wang, C. et al. Hiding a leaf in the forest: uncovering a 1300-year-old homicide case in a 2000-year-old cemetery. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 13, 200 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-021-01459-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-021-01459-1