Indicators of emotional well-being in psychogeriatric care

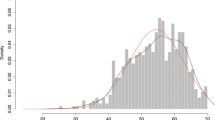

Responses of 1,442 consecutive participants in psychogeriatric day care (mean age 78.8; SD 6.5) to 15 items of a mood questionnaire were analyzed by Mokken scale analysis which is based on nonparametric item response theory models. As from 2002, 825 participants also answered eight self-esteem questions. For the purpose of an exploratory and confirmatory study the sample was split into random halves. The sample represented a broad range of cognitive impairment, from moderately severe to mild dementia. An automated item selection procedure available in the R package mokken revealed a scale for emotional well-being consisting of nine items fitting the monotone homogeneity model of unidimensionality and adequate person separation (Loevingers H = 0.37; SE = 0.02; Cronbach’s coefficient alpha = 0.79; SE = 0.02). A confirmatory analysis in the second random half of the sample confirmed these results. The scale for emotional well-being consists of the items feeling ‘contented’, ‘healthy’, ‘tired’, ‘lonely’, ‘down’, ‘in good spirits’, ‘helpless’, ‘weak’ and ‘having faith in the future’. Mokken scale analysis of the eight self-worth items confirmed the unidimensionality and discriminatory power of the self-esteem scale (H = 0.41; SE = 0.03; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80; SE = 0.02). Emotional well-being was positively associated with self-worth (Spearman correlation = 0.56; 95%-confidence interval [0.49;0.62]). The two scales allow the objective ordering of persons on the latent variables of emotional well-being and self-worth by their test scores. Three case vignettes illustrate application of the indicators in clinical psychogeriatric practice.

Samenvatting

De antwoorden van 1.442 opeenvolgende deelnemers aan psychogeriatrische dagbehandeling (gemiddelde leeftijd 78,8 jaar; SD 6,5) op vijftien items van een stemmingsvragenlijst werden geanalyseerd op basis van het niet-parametrische schaalmodel van Mokken. Vanaf 2002 waren voor 825 deelnemers ook antwoorden op een vragenlijst voor zelfwaardering beschikbaar. Het niveau van cognitief functioneren van de deelnemers varieerde over een brede range, van −6 tot +4 op de korte versie van de Amsterdamse Dementie-Screeningstest (ADS3). Exploratief onderzoek (in de helft van de steekproef) naar unidimensionaliteit en discriminerend vermogen van de stemmingsitems leverde een Schaal voor Emotioneel Welbevinden op van negen items (Loevingers H = 0,37; SE = 0,02; Cronbachs coëfficiënt alfa = 0,79; SE = 0,02). De resultaten werden in een confirmatief onderzoek bij een tweede, onafhankelijke steekproef bevestigd. De Schaal voor Emotioneel Welbevinden bestaat uit de items ‘tevreden’, ‘gezond’, ‘moe’, ‘eenzaam’, ‘somber’, ‘opgewekt’, ‘hulpeloos’, ‘zwak’, en ‘toekomst’. Onderzoek van de acht zelfwaarderingsitems bevestigde de unidimensionaliteit en het discriminerend vermogen van een schaal voor globale zelfwaardering (H = 0,41; SE = 0,03; Cronbachs alfa = 0,80; SE = 0,02). Spearmans rangcorrelatie tussen somscores op de Schaal voor Emotioneel Welbevinden en de Zelfwaarderingsschaal was 0,56 (95%-betrouwbaarheidsinterval [0,49;0,62]). Met de twee schalen beschikt de klinisch werkzame psycholoog over instrumenten om personen objectief te ordenen op de latente eigenschappen emotioneel welbevinden en zelfwaardering. Toepassing in de psychogeriatrische praktijk wordt geïllustreerd aan de hand van drie casusvignetten.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literatuur

Jonker C, Gerritsen DL, Van der Steen JT, Bosboom PR, Van Campen C, Kleemans AHM, et al. Kwaliteit van leven en dementie. I. Model om welbevinden bij demente patiënten te meten. Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie 2001;32:252–258.

Dröes RM, Boelens-Van der Knoop ECC, Bos J, Meihuizen L, Ettema TP, Gerritsen DL, et al. Quality of life in dementia in perspective: an exploratory study of variations in opinions among people with dementia and their professional caregivers, and in literature. Dementia. The International Journal of Social Research and Practice 2006;5:533–558.

Gerritsen DL, Dröes RM, Ettema TP, Boelens E, Bos J, Meihuizen J, et al. Kwaliteit van leven bij dementie. Opvattingen onder mensen met dementie, hun zorgverleners en in de literatuur. Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie 2010;41:241–255.

Downs M. Person-centered care as supportive care. In: Hughes JC, Lloyd-Williams M, Sachs GA, editors. Supportive care for the person with dementia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010: 235–244.

Lawton MP, Moss MS, Winter L, Hoffman C. Motivation in later life: personal projects and well-being. Psychology and Aging 2002;17:539–547.

Bohlmeijer E, Westerhof G, Bolier L, Steeneveld M, Geurts M, Walburg J. Welbevinden: van bijzaak naar hoofdzaak. Over de betekenis van de positieve psychologie. De Psycholoog 2013;48 (november):49–59.

Marcoen A, Van Cotthem K, Billiet K, Beyers W. Dimensies van subjectief welbevinden bij ouderen. Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie 2002;33:156–165.

Van der Steen JT, Van Campen C, Bosboom PR, Gerritsen DL, Kleemans AHM, Schrijver TL, et al. Kwaliteit van leven en dementie. II. Selectie van een meetinstrument voor welbevinden op ‘modelmaat’. Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie 2001;32:259–264.

Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L. Assessing quality of life in older adults with cognitive impairment. Psychosomatic Medicine 2002;64:510–519; http://www.dementia-assessment.com.au/quality/QOL_handout_guidelines_scale.pdf.

Beekman ATF, Van Limbeek J, Deeg DJH, Wouters L, Van Tilburg W. Een screeningsinstrument voor depressie bij ouderen in de algemene bevolking: de bruikbaarheid van de Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie 1994;25:95–103.

Kok RM, Heeren TJ, Van Hemert AM. De Geriatric Depression Scale. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie 1993;35:416–421.

Kok RM. Zelfbeoordelingsschalen voor depressie bij ouderen. Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie 1994;25:150–156.

Hulstijn EM, Deelman BG, De Graaf A, Berger H. De Zung-12: een vragenlijst voor depressiviteit bij ouderen. Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie 1992;23:85–93.

Cahn LA, Cahn-Hut L. A new method of discovering depression in old people. In: XII. International Congress of Gerontology. Hamburg: International Association of Gerontology, 1981: 276.

Cahn LA. Moeilijkheden bij de diagnostiek van de depressie bij bejaarden. Nieuwe aanwinsten bij de diagnostiek. In: Bayens JP, editor. 6de Winter-Meeting. Oostende: Belgische Vereniging voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie, 1983: 39–53.

Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press, 1976.

Frances A, First M. Stemming en stoornis. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Nieuwezijds, 1999.

Helbing JC. Zelfwaardering: meting en validiteit. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor de Psychologie 1982;37:257–277.

Diesfeldt HFA. Zelfwaardering en dementie. In: Goossens L, Hutsebaut D, Verschueren K, editors. Ontwikkeling en levensloop. Leuven: Universitaire Pers Leuven, 2004: 411–429.

Diesfeldt HFA. De Depressielijst voor stemmingsonderzoek in de psychogeriatrie. Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie 1997;28:113–118.

Diesfeldt HFA. De Depressielijst voor stemmingsonderzoek in de psychogeriatrie: meetpretenties en schaalbaarheid. Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie 2004;35:224–233.

Diesfeldt HFA. Globale zelfwaardering bij dementie. Betrouwbaarheid en validiteit van Brinkmans Zelfwaarderingsschaal. Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie 2007;38:122–133.

Ellis JL. Statistiek voor de psychologie, deel 5: factoranalyse en itemanalyse. Den Haag: Boom Lemma, 2013.

Dykstra PA. Loneliness among the never and formerly married: the importance of supportive friendships and a desire for independence. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 1995;50B:S321-S329.

Van Baarsen B. Theories on coping with loss: the impact of social support and self-esteem on adjustment to emotional and social loneliness following a partner’s death in later life. Journal of Gerontology: SOCIAL SCIENCES 2002;57b:S33-S42.

Cahn LA, Diesfeldt HFA. Psychologisch onderzoek van psychisch gestoorde bejaarden met behulp van diapositieven. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie 1973;4:256–263.

De Graaf A, Deelman BG. Cognitieve Screening Test. Lisse: Swets en Zeitlinger, 1991.

Grigsby J, Kaye K. The Behavioral Dyscontrol Scale: Manual. Denver: University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, 1992.

Lindeboom J, Jonker C. Amsterdamse Dementie-Screeningstest. Lisse: Swets and Zeitlinger, 1989.

Lindeboom J, Jonker C. Een korte test voor dementie-screening. Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie 1988;19:97–102.

Sijtsma K, Molenaar IW. Introduction to nonparametric item response theory. London: Sage, 2002.

Molenaar IW, Van Schuur WH, Sijtsma K, Mokken RJ. MSPWIN 5.0 A program for Mokken scale analysis for polytomous items. Groningen: Science Plus Group, 2002.

Van der Ark L. Stochastic ordering of the latent trait by the sum score under various polytomous IRT models. Psychometrika 2005;70:283–304.

Van der Ark LA. New developments in Mokken Scale Analysis in R. Journal of Statistical Software 2012;48:1–27.

Zhang Z, Yuan KH. Robust coefficient alpha for non-normal and missing data: The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, Van der Horst H, Jadad AR, Kromhout D, et al. How should we define health? British Medical Journal 2011;343:d4163.

Kline RB. Beyond significance testing. Washington DC: American Psychological Association, 2004.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Second edition. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1988.

Crawford JR, Garthwaite PH, Slick DJ. On percentile norms in neuropsychology: proposed reporting standards and methods for quantifying the uncertainty over the percentile ranks of test scores. The Clinical Neuropsychologist 2009;23:1173–1195.

Westerhof GJ, Keyes CLM. Mental illness and mental health: the two continua across the lifespan. Journal of Adult Development 2010;17:110–119.

Beerens HC, Sutcliffe C, Renom-Guiteras A, Soto ME, Suhonen R, Zabalegui A, et al. Quality of life of and quality of care for people with dementia receiving long term institutional care or professional home care: The European RightTimePlaceCare Study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2013.

Seligman ME. Helplessness. On depression, development, and death. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, 1975.

Steverink N, Lindenberg S. Which social needs are important for subjective well-being? What happens to them with aging? Psychology and Aging 2006;21:281–290.

Drenth PJD, Sijtsma K. Testtheorie. Inleiding in de theorie van de psychologische test en zijn toepassingen. Houten: Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum, 2006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(XLS 25 kb)

Appendices

Bijlage 1. De 15 trefwoorden uit de Depressielijst in volgorde van aanbieding, met ondersteunende vragen en antwoordalternatieven

-

1

Tevreden Voelt u zich tevreden? 0 = tevreden; 1 = het gaat wel zo; 2 = ontevreden

-

2

Slapen Hoe gaat het met slapen? 0 = goed; 1 = niet zo goed; 2 = slecht

-

3

Eten Hoe is uw eetlust? 0 = goede eetlust; 1 = niet zo goede eetlust; 2 = slechte eetlust

-

4

Gezond Voelt u zich gezond? 0 = voelt zich gezond; 1 = niet zo gezond; 2 = voelt zich ziek

-

5

Moe Bent u vaak moe? 0 = nooit moe; 1 = wel eens of vlug moe; 2 = steeds vermoeid

-

6

Oud Voelt u zich oud? 0 = voelt zich nog niet oud; 1 = voelt zich toch wel oud; 2 = voelt zich erg oud

-

7

Eenzaam Voelt u zich eenzaam? 0 = nooit of zelden eenzaam; 1 = soms wel eenzaam; 2 = voelt zich dikwijls eenzaam

-

8

Vrienden Heeft u vrienden? 0 = enkele of veel vrienden en/of kennissen; 1 = wel wat aanspraak; 2 = geen vrienden of kennissen

-

9

Bezoek Krijgt u genoeg bezoek? 0 = tevreden met bezoek, komt genoeg; 1 = meer bezoek zou prettig zijn; 2 = ontevreden over bezoek

-

10

Somber Bent u wel eens somber? 0 = nooit of zelden; 1 = soms; 2 = dikwijls

-

11

Verveling Verveelt u zich wel eens? 0 = verveelt zich zelden of nooit; 1 = soms; 2 = dikwijls

-

12

Opgewekt Bent u een opgewekt persoon? 0 = meestal opgewekt; 1 = niet zo erg opgewekt; 2 = meestal niet of weinig opgewekt

-

13

Hulpeloos Voelt u zich hulpeloos? 0 = voelt zich niet hulpeloos; 1 = voelt zich soms wel hulpeloos; 2 = voelt zich dikwijls hulpeloos

-

14

Zwak Voelt u zich lichamelijk zwak? 0 = voelt zich niet zwak; 1 = voelt zich soms zwak, of vrij zwak; 2 = voelt zich zwak

-

15

Toekomst De tijd die voor u ligt, kan dat nog een plezierige tijd voor u zijn? 0 = verwacht nog wel wat van het leven; 1 = ziet er niet zo veel meer in; 2 = ziet er niets of heel weinig in

Bijlage 2. Zelfwaarderingsvragen (en antwoordmogelijkheden) in volgorde van aanbieding

-

1

Ik ben tamelijk zeker van mezelf (nee = 0; min of meer = 1; ja = 2)

-

2

Bij mij gaat alles fout (nee = 2; min of meer = 1; ja = 0)

-

3

Ik sta positief ten opzichte van mezelf (nee = 0; min of meer = 1; ja = 2)

-

4

Ik zou een heleboel aan mezelf willen veranderen (nee = 2; min of meer = 1; ja = 0)

-

5

Soms voel ik me nutteloos (nee = 2; min of meer = 1; ja = 0)

-

6

In het algemeen heb ik weinig vertrouwen in mijn capaciteiten (nee = 2; min of meer = 1; ja = 0)

-

7

Ik heb een lage dunk van mezelf (nee = 2; min of meer = 1; ja = 0)

-

8

Over het geheel genomen ben ik tevreden met mezelf (nee = 0; min of meer = 1; ja = 2)

Bijlage 3

About this article

Cite this article

Diesfeldt, H.F.A. Indicatoren van emotioneel welbevinden in de psychogeriatrische praktijk. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr 46, 137–151 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12439-014-0107-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12439-014-0107-z