Abstract

Minority groups and immigrants encounter complex issues when attempting to access healthcare. This study examines factors affecting access to healthcare by a group of individuals in Israel who decided to leave their Haredi Jewish communities. We conducted 23 semi-structured interviews with individuals disaffiliating from Haredi communities in Israel in order to identify hurdles encountered during the process of seeking healthcare. We focused on specific steps in this process, including recognizing the need for help, deciding to actually turn to the health system, interaction with the system, and behavior after referring to the health system. We identified approximately 20 factors which can be either barriers or catalysts affecting healthcare access at the various stages. These were then traced to religious upbringing, hurdles of sociocultural transition, and unique characteristics of individuals reshaping their lives. The findings can be instrumental in designing culturally adapted health programs for individuals leaving the Haredi community. Moreover, the methodology that we are proposing can serve other investigations studying access to healthcare among various groups undergoing sociocultural transitions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Disaffiliation from Orthodoxy is a phenomenon found in most Jewish communities worldwide. In Israel, this trend has become more pronounced in recent years. Although there is some disagreement over the rate of disaffiliation from the ultra-Orthodox community, which is identified in Israel as Haredi (lit. those who fear), a recent report showed that 88% of those who grew up in the Haredi community adhere to this lifestyle through adulthood. An additional 4% define themselves as religious but not Haredi, 6% define themselves as traditional, and 2% as fully secular (Ben-David 2019). Based on reports from organizations who provide aid and support for disaffiliates, this rate increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The reasons for disaffiliation are complex, and often motivated by “origin factors,” pushing a person to leave a community, and “destination factors,” pulling a person to join a new community. Nevertheless, irrespective of the reasons for disaffiliation, leaving a familiar milieu and standing up against pressure from family and peers requires a great deal of resilience.

Previous studies have compared religious disaffiliates to immigrants (Engelman et al. 2020; Berger 2014; Davidman 2015). Similar to other typical immigration processes, the disaffiliation process entails significant vulnerabilities. Disaffiliation from the Haredi community is a taxing personal process that involves major social, logistic, and financial challenges (Berger 2015; Velan and Pinchas-Mizrachi 2019). In early years following their disaffiliation, individuals have to learn to tackle major social gaps, survival, logistics, and financial challenges (Davidman and Greil, 2007). Disaffiliates are preoccupied with closing gaps related to education, finding housing and jobs, and interacting with the opposite sex. All this may affect their ability to access and utilize the health system and manage their health needs.

In this study, we focus on the health of population groups defined by transition from one sociocultural background (as defined by life course, norms, perceptions, and habits) to another within the boundaries of the same country. A classic example of this would be the subpopulation of Haredi Israeli Jews who choose to leave their ultra-Orthodox society of origin, and create a new identity for themselves as non-Haredi Jews (Doron 2013).

In a previous study we addressed some of the health concerns pertaining to these disaffiliates, and demonstrated shortcomings related to mental health, sexual health, and risky behavior (Velan and Pinchas-Mizrachi 2019). In the present study, we examine the access and utilization of healthcare among these disaffiliates. To this end, we analyze health behaviors associated with their upbringing in the insular Haredi communities (Glinert and Shilhav 1991) and behaviors associated with the disaffiliation process itself.

Disparities in access to healthcare and health services are often identified with minority groups such as immigrants (Hjern et al. 2001; Szczepura 2005), ethnic groups (Mui et al. 2017), religious minorities (Dilmaghani 2018), and sexual minorities (Blondeel et al. 2016; Szczepura 2005; Agudelo-Suárez et al. 2012; Rosano et al. 2017; Manuel 2018; Taylor and Lurie 2004). Accessibility to healthcare is a complex and multifactorial construct that depends on extrinsic/organizational factors such as affordability, location, and differential provisions, and/or on personal factors such as linguistic competence, cultural competence, health literacy, or cultural differences in the perception of healthcare (Andersen 2008; Keith-Lucas 1972; Cassidy et al. 2018).

Many studies have investigated the complexity of access to healthcare among immigrants (Brzoska, 2018; Hall and Cuellar 2016; Abubakar et al. 2016). Immigrants were shown to encounter obstacles associated with adaptation to the unfamiliar health system in their new location and in adapting to their new sociocultural environments (Agudelo-Suárez et al. 2012; Wafula and Snipes 2014; Cristancho et al. 2008).

In spite of the difficulties in accessing healthcare, several studies have shown a “healthy immigrant” phenomenon, characterized by lower mortality rates among immigrants than among native populations (Wallace and Kulu 2015; Singh and Siahpush 2001). These favorable health outcomes have been attributed to a “choice effect,” which posits that individuals who emigrate from their countries of origin by choice are generally more resilient mentally and physically. Moreover, immigrants may become more resourceful and more dedicated to shaping and managing their own fate, including their health status.

Health Behavior of the Haredi Community in Israel

The Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics divides the Jewish population in Israel into four groups based on religiosity: secular, traditionalists [Masortim, adhering to some Jewish traditions and rituals, but not fully religious], religious, and Haredi. Haredi is an umbrella term for several ultra-Orthodox communities consisting of Litvish, Hasidim, Chabad, and Sephardic Haredi groups. Forty-five percent of Israeli Jews identify as secular, about 25% as traditionalist, 16% as religious, and 14% as Haredi (Central Bureau of Statistics 2018).

The Haredi population is a community with special cultural and sociodemographic traits. They are characterized by strict adherence to Jewish law, and by placing premium value on Torah study. Many of the Haredi men choose to study full-time for many years in yeshivas, or Rabbinical seminaries, while their wives work to financially support their families (Gal 2015). Haredi families tend to be large due to the religious adherence to procreation (Birenbaum-Carmeli 2008). In many cases, Haredi families in Israel are dependent on a single income source and thus tend to live under the poverty line (Israel Democracy Institute 2018).

This group is characterized by unhealthy behavior which includes low compliance with mammography screening (Pinchas-Mizrachi et al. 2021a, 2021b), higher obesity rates (Leiter et al. 2020), and low usage of dental care services (Lazarus et al. 2015). An additional consideration in the evaluation of health behavior among Haredi Jews should relate to the fact that previous studies have found that the Haredi community tends to shy away from self-exposure, or revealing one’s vulnerabilities (Band-Winterstein and Freund 2013). Some researchers raised the point that this is manifested by a lack of willingness to share intimate personal details related to physical and mental health, in part based on the fear of harming the family’s reputation, thus ruining the prospects for arranged marriages by social stigmas related to ill health (Greenberg et al. 2012).

At the same time, it should be noted that one of the fundamental principles of the Jewish religion rests upon the value placed on the sanctity of human life. This should lead to promotion and maintenance of good health among Orthodox believers (El-Or 1994; Doron 2013). Many earlier studies have indeed found better health outcomes among the Haredi community in comparison to the non-Haredi Jewish community. These outcomes may be explained by the social capital prevalent among the members of the community (Pinchas-Mizrachi et al. 2021a, 2021b).

In this study we rely on the qualitative analysis of 23 interviews with disaffiliates to examine access to and utilization of healthcare services. To this end, we dissected the process of accessing healthcare into five distinctive steps: (1) recognizing the need for help, (2) deciding to actually seek treatment, (3) making and managing health contacts, (4) interaction with the caregiver, and (5) behavior after referring to the health system. We then consider three potential groups of effectors on the access to health by disaffiliates, related to (a) health behavior acquired during their prior lives as Haredi, (b) specific characteristics imprinted by the mere process of disaffiliation, and (c) vulnerabilities associated with transition into the general society. By juxtaposition of the five steps of accessing and utilizing healthcare and the three major effectors, we reveal a complex interplay of factors, indicating that disaffiliation can engender both barriers and enablers for accessing and utilizing healthcare.

Methods

Study Sample

The study sample comprised 16 men, 22–34 years old, and seven women, 20–29 years old. All participants were raised in Haredi Ashkenazi (of Eastern and Central European origin) Jewish families. Eight participants defined their background as Hasidic, 13 defined their background as Litvish, and two defined their background as “mixed—Hasidic-Litvish.” These interviews were conducted between November 2018 and February 2020. The interviews took place in the researchers’ offices in Ramat Gan and Jerusalem, except for three which took place in coffee shops (as per the requests of the interviewees). The interviews were translated from Hebrew into English by a professional translator. All the names mentioned below in the results section are pseudonyms (for more information on the participants, please see the table in Appendix 1).

Interviews

We conducted interviews in Hebrew using a semi-structured format. First, interviewees were recruited with the help of several organizations that help disaffiliates, including Out for Change, Hillel, and others. Later on, recruitment continued through “snowballing,” where interviewees recruited other people for the study.

The interviews consisted of two parts. In the first part, we asked interviewees to refer to medical problems likely to affect them. Findings related to this part were reported in a previous article (Velan and Pinchas-Mizrachi 2019). In the second part, we asked the interviewees to address accessibility to the health system in Israel and to identify factors that affected their access to the healthcare system.

The ethics committee of the Academic College of Ramat-Gan approved the study in November 2018 (approval number 1318).

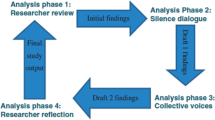

Content Analysis

The major motives in the transcribed interviews were identified by means of content analysis based on an interpretative phenomenological approach (Giorgi 1997). The transcript of each interview was screened for coherent statements, yielding lists of 20–30 statements per interview, all related to accessing healthcare. Examination of all these statements allowed us to identify about 20 factors that appeared to affect participants’ access to healthcare. A factor was recognized as meaningful if it was identified in at least three different interviews.

These factors were then divided into categories based on three criteria:

-

1.

The nature of the effect (obstacle to access or factor that facilitates access)

-

2.

The health-seeking stage affected by the motive (recognizing the need for help, deciding to seek treatment, making and managing health contacts, communicating with the caregiver, and responding to recommendations)

-

3.

The underlying source of each motive (related to the upbringing, to the process of transition, and to the specific traits and outlooks of disaffiliates).

Each researcher categorized these criteria individually. In most cases, the categorization of both researchers was similar; in some cases, differences were resolved after discussing them.

Results

In this study, several barriers and catalysts have been found that characterize the interaction of disaffiliates from the Haredi community vis-à-vis the healthcare services. The obstacles and catalysts to seeking healthcare and factors that facilitated access to healthcare and utilization as discussed by the interviewees are delineated according to five definitive stages in the longitudinal process of making contact with and receiving treatment by the healthcare system.

Recognizing the Need for Help

To decide to seek treatment, disaffiliates must first recognize the need for doing so. At this stage, the upbringing of disaffiliates in the Orthodox community can either facilitate or deter seeking treatment. A number of the participants indicated that Haredi education puts a strong emphasis on the importance of being healthy.

Yitzhak: We were raised with the idea that being very protective of your life is a mitzvah [commandment] from the Torah.

Nevertheless, this abstract notion is accompanied by a lack of attention to practical health information and awareness in the formative years. This can prevent disaffiliates from recognizing the need for treatment when required.

Shimon: They generally don’t teach [Haredi youngsters] about health awareness, and there is also less awareness of it among those who become secular.

Another obstacle in recognizing the need for help is related to the religious tendency of focusing on the positive and ignoring the negative. Haredi Jews are raised to glorify God and to be grateful for what they have, which may prevent recognition of what is lacking.

Leah: If you are Haredi, you are expected to say, “Praised be God, thank God, I’m pleased with what I have.” You can't tell yourself that things are not good.

Moreover, some interviewees expressed a sense that expressions of depression or emotional problems are liable to be interpreted as heresy.

Yaakov: If there is a Creator and you trust Him and believe in Him, how can you dare to be depressed?

Nonetheless, disaffiliates are likely to enjoy a sense of liberation from what they perceive as the shackles of faith of the Haredi lifestyle, which may enable a heightened readiness to admit having emotional problems, and to feel encouraged to seek health assistance.

Aharon: Thank God I became secular. There is no God. You can be angry; you can say that things are hard emotionally; the word “depression” is no longer a problem for you. You can feel free to seek help.

In this sense, the experience of opening a new page in life can facilitate the recognition of the need to seek healthcare.

Deciding to Seek Aid or Treatment

After recognizing the need for medical help, the next stage is to actively seek treatment. According to the interviewees, the primary obstacle at this stage is the social stigma surrounding physical and mental health issues in the Haredi community in which they were raised. Specifically, good health plays a key role in the institution of prearranged marriages in the Orthodox community.

Leah: There’s this secrecy, if I go to a doctor, and am diagnosed with diabetes or something, it’s liable to hamper the chances for arranged marriages for other members of the family. Such issues will be silenced and kept secret.

Rachel: Once it becomes known that someone in the family is using psychiatric medication, this will ruin one’s whole life, and damage the entire family.

Such stigmas, imprinted at a young age, can hinder seeking help, especially mental health treatment, even after leaving the Haredi community.

Binyamin indicated that it is hard to overcome the old habit of not seeking mental health: It’s hard to seek medical assistance, especially mental health assistance. Old habits die hard.

Dan: Every treatment that has the word “psycho” within it means “crazy.”

Disaffiliates carry this baggage, which deters them from going to a psychologist. These concerns relate to the complex feelings that disaffiliates have towards the families they have left. They are afraid of causing further harm to their parents and siblings, but, at the same time, they still need to justify their decision to leave the Haredi community.

Rivka: Not only did I hurt my brothers’ arranged marriage prospects when I left, now I’m also going to be recognized as “crazy”?

Moreover: When I wanted to leave, they told me that I was crazy. If they learn that I am in therapy, it would be proof that they were right and I did go crazy.

-

Making and managing contact with the healthcare system

After deciding to access the healthcare system, disaffiliates are likely to face bureaucratic hurdles. They may not be automatically registered with one of the Israeli health maintenance organizations (HMOs) once they have left their family, and they may be unaware of the need to register.

Avraham: Usually, until one leaves, parents take care of payments, but when one decides to leave, this can change. Some fathers may cancel the monthly payments and you remain without health insurance.

In addition, many of the interviewees mentioned their preoccupation with daily survival as an obstacle to seeking treatment for a physical or emotional problems.

Yaakov: You work at two or three jobs to survive… How can you find time to deal with your health problems?

The strain of the transition also has financial implications. Although healthcare in Israel is highly subsidized, financial constraints may prevent disaffiliates from seeking healthcare in the private sector when needed. This is particularly relevant when seeking psychotherapy.

Rivka: Now you have to wait six months for an appointment [using the public system] … If you have the money for private care, it can be done in half an hour… I’d have to work 20 hours in order to pay for an hour of psychotherapy.

The interviewees also mentioned difficulties in dealing with seemingly trivial matters related to using the Israeli healthcare system.

A yeshiva student does not contact a doctor on his own. Parents do it for him and may go with him.

Yael: Scheduling and going to an appointment with a doctor seems like a difficult task. It’s sometimes hard to function in such a chaotic and unknown environment.

These trivial complaints often relate to the fact that healthcare interactions were previously mediated by mothers.

Interviewees also referred to a unique mechanism developed by the Israeli Haredi community, that of reliance on an expert “health broker.” These are volunteers within the Haredi community who are considered knowledgeable about the Israeli healthcare system and often act on behalf of charity organizations in the community. They assist sick people in finding the right medical experts to treat their illnesses. In recent years, the Israeli HMOs have recruited such individuals, recognizing their important role in bridging cultural gaps between Haredi individuals and the medical and administrative staff of the HMOs. This effective system is no longer available for individuals who have left the community.

Yaakov: We need someone to arrange things for us… When I was Haredi, if I needed surgery… One call to the right broker and you’re…at the front of the line.

Nevertheless, it is important to remember that individuals making the transition from a familiar to an unfamiliar milieu are generally resourceful. Many manage to deal with basic issues of survival such as earning a living, finding housing, and acquiring an education, and therefore one may think that this resourcefulness could help them find ways of overcoming the hurdles of accessing and utilizing the healthcare system.

-

Communicating with the caregiver

Once the contact with the healthcare professional is established, disaffiliates have to deal with the actual utilization of the healthcare system in terms of face-to-face interactions with the caregiver (Greenberg et al. 2012; Band-Winterstein and Freund 2013). Haredi education includes specific directives regarding modesty and discretion, and restrictions surrounding myriad topics of conversation, all of which likely affect the behavior of disaffiliates when meeting with physicians.

Dan: One is not comfortable telling the doctor, for instance, that his testicles hurt. So, he won’t say it.

Rachel: Until a year ago, I was a modest God-fearing Jewish girl. Going to a male gynecologist and getting undressed would be very unpleasant.

Emotional exposure can be as difficult as physical exposure. Sharing sensitive issues such as one’s mental or emotional state is difficult.

Shimon: We were raised to not really know how to connect or express emotions. This is something from home; it’s hard to talk about feelings or problems in general, even when you go to a professional.

This may stem from the fact that Talmudic and biblical literature regards forms of mental illness and other disabilities as “blemishes” (Pollak and Freeman 2008).

In addition to these obstacles, disaffiliates may be unfamiliar with the various codes of conduct with healthcare professionals, which can further hinder their ability to communicate freely and openly when seeking healthcare.

Yael: They find themselves in a foreign society, not knowing the codes… They may not know how to express themselves when seeing a doctor.

Post-Contact Conduct: Complying with Recommendations

On one hand, the culture of obedience, including respect for authority (Gal, 2015), in which the Haredi are raised may actually strengthen their resolve to adhere to health recommendations. In this sense, the Orthodox background serves as an enabler.

Yael: You grow up in a world where the parents and the rabbis tell you what to do, and you do it.

The authority of the doctor is therefore highly respected.

The most "important" Rabbi, when he’s sick, will go to the best doctor, even if he’s a heretic. A good doctor is like God. You listen to everything he says.

However, this obedience could be the first thing that disaffiliates would like to shed after leaving. Participants in our study often characterized themselves, and others like them, as rebels, breaking the conventions of the milieu from which they came, but not necessarily accepting the conventions of the milieu they had joined. Newfield (2020) categorizes such disaffiliates as “trapped,” since they are unable to reconcile elements of their newly found lives with elements from their former Haredi ones.

Leah: Disaffiliates have severed their ties to their past, obedience to God, to their parents, so now they break the rules all the way.

Moreover, their new lifestyle can lead to the practice of dangerous and unhealthy behavior (Velan and Pinchas-Mizrachi 2019) as well as to a lack of compliance with healthcare recommendations.

Yael: I stopped obeying God, so you want me to obey a doctor?

Another factor that can affect healthcare conduct during treatment relates to the absence of social support that provides comfort and help during recovery from an illness.

Yaakov: Suddenly, in an instant, you’re thrown out of your world. If you have a problem, no one in the world will help you.

The lack of family and communal support that is traditionally abundant within Haredi society leaves disaffiliates entirely alone.

Summary of Results

This research reveals a number of factors that prevent or facilitate access to and utilization of healthcare and willingness to adhere to medical advice. These factors are related to various aspects of their lives, including their Haredi upbringing, the trajectory of the journey from the Haredi to the secular world, and the specific outlooks of people who have acted on their decision to break boundaries. Table 1 lists the various obstacles and enablers delineated along the five stages of response to healthcare grouped according to contributory life experience.

Discussion

In recent years, many young Israelis have left the Haredi community to join the secular world, resulting in the emergence of a new subpopulation, a minority defined by its unique sociocultural characteristics. In a previous study (Velan and Pinchas-Mizrachi 2019), we examined the potential predisposition of these individuals to illness, and identified disparities associated with mental health, sexual health, and healthy behavior. In this study, we examine the various factors that may affect their access to healthcare and utilization of medical services. Content analysis of interviews conducted with 23 individuals who recently made the transition from Haredi to the secular revealed close to 20 potential factors that may affect access to and utilization of healthcare.

These factors can be categorized by their effect on the five typical stages that define access to healthcare from the recognition of the need to the response to the recommended treatment, as well as by the outcome of the effect (barrier versus enablers) or by the underlying origins of the effect (see below).

In this section, we analyze the effects of disaffiliation on health seeking by examining three distinct underlying motives: effectors related to the particular social background of disaffiliates, to their status as a transitioning population, and to the inherent characteristics of individuals who have found the courage to break social boundaries and adopt new identities.

Effectors Connected to Sociocultural Backgrounds

Disaffiliates opted to leave their community and lifestyle. Yet, elements of their former life remain ingrained in their behavior, accompanying them throughout their contact with the healthcare system. At least eight factors mentioned by the interviewees in their accounts of interactions with the healthcare system can be traced to their experience in the Haredi community (Table 1, second column).

The Haredi community in Israel can be characterized as an insular, hierarchical, traditional group with strong adherence to religious commandments and very defined perceptions on most aspects of life, including health (Doron 2013; El-Or 1994; Freund et al. 2019, 2014; Gal, 2015). All of the interviewees agreed that specific Haredi perceptions about health still affect their attitudes and behavior. They indicated that lack of health-oriented education, fatalism, strong adherence to modesty, difficulties in disclosure of problems, and the stigmas attributed to illness are obstacles in their interaction with the healthcare system. In contrast, belief in the sacredness of life and respect for authority, both acquired during their formative years, may act as enablers in accessing healthcare.

These observations reflect the dichotomy in the approach of Haredi society to health: On one hand, religious perceptions may distance one from the “mundane” health-related issues that result in a serious ignorance of the subject (Coleman-Brueckheimer and Dein 2011; Lazarus et al. 2015). On the other hand, Haredi society places a high priority on good health based on the biblical command to protect your health “with the utmost of care.” This can result in seeking healthcare, respecting the medical profession, and developing elaborate social mechanisms for accessing healthcare.

The importance given to good health may also have adverse effects, as it tends to stigmatize the unhealthy, and perceives them to be unsuitable for prearranged marriages (McEvoy et al. 2017; Coleman-Brueckheimer and Dein 2011), possibly resulting in the nondisclosure of health problems.

The effect of sociocultural factors on access to and utilization of healthcare is obviously not unique to disaffiliates from the Jewish Haredi community, and has been discussed in numerous studies of various ethnic minorities and immigration groups (Brzoska 2018; Hall and Cuellar 2016; Abubakar et al. 2016). Our study draws attention to groups in the process of transitioning from a traditional society into a secular one. With the increasing influx of immigrants from developing countries to developed countries and from traditional to more secular, modern societies, these issues will be seen more frequently. Healthcare systems should be aware of the cultural heritage of newcomers to facilitate their access to healthcare.

Obstacles Connected to the Transitioning Process

Other obstacles, primarily structural, are related to the actual process of transitioning (Table 1, third column). In the early stages of their departure from the Haredi world, young exiters undergo a dramatic lifestyle shift, are rejected by their families, rabbis, and communities, and must be able to support themselves financially. This is particularly difficult since their ultra-Orthodox upbringing did not provide them with a secular education, a matriculation certificate, professional training, or relevant life skills. (Topel 2012). This set of circumstances can thrust the young person into a “survival mode,” constantly coping with acute pressures and challenges, adding more obstacles in approaching medical and mental health services within the Israeli public health system. Moreover, these obstacles are even greater when disaffiliates require privatized healthcare.

Another factor affecting the lives of disaffiliates is the severing of ties with their family and disconnection from their communities, which had offered a broad social support system (Pines and Zaidman 2003). This leaves them alone to overcome the bureaucratic hurdles of establishing contact with the healthcare system. More important are the emotional implications of isolation and loneliness that are likely to influence their contact with the healthcare system and their ability to cope with potentially serious medical problems.

Haredi know Hebrew in the context of the spoken language and as a holy language. However, there are differences between the spoken Hebrew language in the Haredi community and that in the general population, including the healthcare system. These differences, together with cultural disparities, exposes disaffiliates to a society and a healthcare system that speaks a different language and adheres to different cultural norms, rules, and behavioral codes, which may be incomprehensible to the new sociocultural “implant.” This is similar to the cultural gaps immigrants experience, which can negatively affect the process of requesting assistance or treatment or receiving treatment (Taylor and Lurie 2004; Wafula and Snipes 2014).

Obstacles and Enablers Connected to Personality Characteristics and Outlooks

In their decision to leave Haredi society, disaffiliates embark on a difficult journey that requires courage and character. In the spirit of the “healthy immigrant” phenomenon (Singh and Siahpush 2001; Wallace and Kulu 2014, 2015), we suggest that the exit from the Haredi community requires high levels of coping abilities and resourcefulness, which, in many instances, may be a source of strength and facilitate the process of initiating and maintaining contact with the healthcare system (Table 1, fourth column). In a study conducted among formerly Orthodox Lubavitch and Satmar Hasidim in New York, the author draws a parallel between disaffiliates from the Orthodox communities and immigrants. He does point out a significant difference suggesting that immigrants may face racial or cultural discrimination when arriving in a foreign land, whereas disaffiliates from the Orthodox community are generally embraced by their new society (Newfield 2020).

The inherent tendency of breaking boundaries has two contradictory effects. It can lead to a rejection of all authority and an unwillingness to cooperate with health authorities, or it can lead to an increased willingness to engage in "new beginnings" and reject the health stigmas and hurdles associated with Haredi society. The transition experience can be an introspective process, strengthening individualism and self-indulgence, acceptance of personal well-being, and acknowledgement of their mental and physical states.

Taken together, the analysis of the interviews presented here suggests that the background and life experiences of disaffiliates can engender obstacles to their access to health services at various stages. At the same time, the personal resources of individuals who decide to engage in a strenuous sociocultural transition, and manage to overcome significant hurdles, may help them find a way to effectively access the healthcare system.

Limitations

This study is based upon interviews with 23 disaffiliates from Haredi Ashkenazi society in Israel. The interviews were mainly conducted in the early years after their exit. This may be reflected sometimes in the emotional attitude towards the Haredi community, and the tone of complaints and grievances in some of the interviews. Therefore, the extent of continued struggles with the healthcare system would require further study.

In addition, it is important to note that the relatively small sample size in this study did not allow for analysis of the effects of sex, age, ethnicity, time elapsed since exit, familial status, etc.

Conclusions

This study focuses on the factors that may affect access to healthcare of an emerging sociocultural subpopulation in Israel: young men and women who decide to leave the Haredi Jewish society and assimilate into the mainstream population. By careful content analysis of interviews conducted with 23 such individuals, we have delineated obstacles in accessing healthcare and factors that facilitate accessing healthcare. This analysis makes an important contribution to policymakers responsible for designing culturally adapted health programs for disaffiliates. Moreover, this study can be extended to in-depth analysis of specific health issues that are very relevant to disaffiliates. These may include seeking psychological help, relating to body image perceptions, and addressing sexual problems.

In addition, the approach proposed here can be adapted to the study of access to health of other populations in transit. On one hand, access to healthcare can be described as a multistage process consisting of recognizing the need for help; the decision to seek treatment; making and managing health contacts; communicating with the caregiver; and responding to recommendations. On the other hand, the potential effectors can be divided into those related to imprints of the old world left behind; those related to the process of transition itself; and those related to the specific traits of individuals choosing to leave the familiar and move towards a new world.

References

Abubakar, Ibrahim, Delan Devakumar, Nyovani Madise, Peter Sammonds, Nora Groce, Cathy Zimmerman, Robert W. Aldridge, Jocalyn Clark, and Richard Horton. 2016. UCL-lancet commission on migration and health. Lancet 388: 1141–1142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31581-1.

Agudelo-Suárez, Andres A., Diana Gil-González, Carmen Vives-Cases, John G. Love, Peter Wimpenny, and Elena Ronda-Pérez. 2012. A metasynthesis of qualitative studies regarding opinions and perceptions about barriers and determinants of health services’ accessibility in economic migrants. BMC Health Services Research 12: 461. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-461.

Andersen, Ronald Max. 2008. National health surveys and the behavioral model of health services use. Medical Care 46: 647–653. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0b013e31817a835d.

Band-Winterstein, Tova, and Anat Freund. 2013. Is it enough to “Speak Haredi”? Cultural sensitivity in social workers encountering Jewish ultra-orthodox clients in Israel. British Journal of Social Work 45: 968–987. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct167.

Ben-David, Dan. 2019. Doing (learning) the math in Israel: Conflicting demographic trends and the core curriculum. Tel-Aviv, Israel: Shoresh Institution for Socioeconomic Research.

Berger, Roni. 2014. Leaving an insular community: The case of ultra orthodox Jews. Jewish Journal of Sociology 56: 75–98.

Berger, Roni. 2015. Challenges and coping strategies in leavening an ultra-orthodox community. Qualitative Social Work: Research and Practice 14: 670–686. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325014565147.

Birenbaum-Carmeli, Daphna. 2008. Your faith or mine: A pregnancy spacing intervention in an ultra-orthodox Jewish community in Israel. Reproductive Health Matters 16: 185–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(08)32404-5.

Blondeel, Karel, Lale Say, Doris Chou, Igor Toskin, Rajat Khosla, Elisa Scolaro, and Marleen Temmerman. 2016. Evidence and knowledge gaps on the disease burden in sexual and gender minorities: A review of systematic reviews. International Journal for Equity in Health 15: 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0304-1.

Brzoska, Patrick. 2018. Disparities in health care outcomes between immigrants and the majority population in Germany: A trend analysis, 2006–2014. PLoS ONE 13: e0191732. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191732.

Cassidy, Christine, Andrea Bishop, Audrey Steenbeek, Donald Langille, Ruth Martin-Misener, and Janet Curran. 2018. Barriers and enablers to sexual health service use among university students: A qualitative descriptive study using the Theoretical Domains Framework and COM-B model. BMC Health Services Research 18: 581. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3379-0.

Central Bureau of Statistics. 2018. Society in Israel: Religion and self-definition of religiosity (No. 10).

Coleman-Brueckheimer, Kate, and Simon Dein. 2011. Health care behaviours and beliefs in Hasidic Jewish populations: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Religion and Health 50: 422–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9448-2.

Cristancho, Sergio, D. Marcela Garces, Karen E. Peters, and Benjamin C. Mueller. 2008. Listening to rural hispanic immigrants in the Midwest: A community-based participatory assessment of major barriers to health care access and use. Qualitative Health Research 18: 633–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732308316669.

Davidman, Lynn. 2015. Becoming un-orthodox: Stories of ex-Hasidic Jews. Cary, NC: Oxford University Press.

Davidman, Lynn, and Arthur L. Greil. 2007. Characters in search of a script: The exit narratives of formerly ultra-orthodox Jews. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 46: 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2007.00351.x.

Dilmaghani, Maryam. 2018. Religious identity and health inequalities in Canada. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 20: 1060–1074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0640-2.

Doron, Shlomi. 2013. Leaving the ultra-orthodox society as an encounter between social-religious models. Israeli Sociology 2: 373–390.

El-Or, Tamar. 1994. Educated and ignorant: Ultraorthodox Jewish women and their world. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Engelman, Joel, Glen Milstein, Irvin Sam Schonfeld, and Joshua B. Grubbs. 2020. Leaving a covenantal religion: Orthodox Jewish disaffiliation from an immigration psychology perspective. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 23: 153–172.

Freund, Anat, Miri Cohen, and Faisal Azaiza. 2014. The doctor is just a messenger: Beliefs of ultraorthodox Jewish women in regard to breast cancer and screening. Journal of Religion and Health 53: 1075–1090. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9695-0.

Freund, Anat, Miri Cohen, and Faisal Azaiza. 2019. A culturally tailored intervention for promoting breast cancer screening among women from faith-based communities in Israel: A randomized controlled study. Research on Social Work Practice 29: 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731517741197.

Gal, Reuven. 2015. The Haredim in Israeli Society. Samuel Neaman Institute for National Policy Research. The Technion, Haifa. https://www.neaman.org.il/Files/6-425.pdf

Giorgi, Amedeo. 1997. The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology 28: 235–260. https://doi.org/10.1163/156916297X00103.

Glinert, Lewis, and Yosseph Shilhav. 1991. Holy land, holy language: A study of an Ultraorthodox Jewish ideology. Language in Society 20: 59–86.

Greenberg, David, Jacob Tuvia Buchbinder, and E. Eliezer Witztum. 2012. Arranged matches and mental illness: Therapists’ dilemmas. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes 75: 342–354. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2012.75.4.342.

Hall, Eleanor, and Norma Graciela Cuellar. 2016. Immigrant health in the United States: A trajectory toward change. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 27: 611–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659616672534.

Hjern, Anders, Bengt Haglund, G. Gudrun Persson, and Mans Roen. 2001. Is there equity in access to health services for ethnic minorities in Sweden? The European Journal of Public Health 11: 147–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/11.2.147.

Israel Democracy Institute. 2018. Statistical report on ultra-orthodox (Haredi) Society in Israel 2017. https://en.idi.org.il/media/10441/statistical-report-on-ultra-orthodox-society-in-israel-2017.pdf

Keith-Lucas, Alan. 1972. Giving and taking help. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Lazarus, Zoe, Steven Pirutinsky, Miriam Korbman, and David H. Rosmarin. 2015. Dental utilization disparities in a Jewish context: Reasons and potential solutions. Community Dental Health 32: 247–251.

Leiter, Elisheva., Keren L. Greenberg, Milka Donchin, Osnat Keidar, Sara Siemiatycki, and Donna R. Zwas. 2020. Cardiovascular disease risk factors and health behaviors of ultra-orthodox Jewish women in Israel: A comparison study. Ethnicity & Health, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2020.1849567.

Manuel, Jennifer I. 2018. Racial/ethnic and gender disparities in health care use and access. Health Services Research 53: 1407–1429. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12705.

McEvoy, Phil, Tracey Williamson, Raphael Kada, Debra Frazer, Chardworth Dhliwayo, and Linda Gask. 2017. Improving access to mental health care in an Orthodox Jewish community: A critical reflection upon the accommodation of otherness. BMC Health Services Research 17: 557. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2509-4.

Mui, Paulani, Janice V. Bowie, Hee-Soon. Juon, and Roland J. Thorpe Jr. 2017. Ethnic group differences in health outcomes among Asian American men in California. American Journal of Men’s Health 11: 1406–1414. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988316664508.

Newfield, Schneur Zalman. 2020. Degrees of separation: Identity formation while leaving ultra-orthodox Judaism. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Pinchas-Mizrachi, Ronit, Amy Solnica, and Nihaya Daoud. 2021a. Religiosity level and mammography performance among Arab and Jewish women in Israel. Journal of Religion and Health. 60: 1877–1894.

Pinchas-Mizrachi, Ronit, Beth G. Zalcman, and Ephraim Shapiro. 2021b. Differences in mortality rates between Haredi and non-Haredi Jews in Israel in the context of social characteristics. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 60: 274–290.

Pines, Ayala Malach, and Nurit Zaidman. 2003. Israeli Jews and Arabs: Similarities and differences in the utilization of social support. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 34: 465–480.

Pollak, Shulamis, and Joy E. Freeman. 2008. Alexithymia among Orthodox Jews: The role of object relations, family emotional expressiveness, and the presence of a disabled sibling. Disability Studies Quarterly 28: 3. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v28i2.97.

Rosano, Aldo, Marie Dauvrin, Sandra C. Buttigieg, Elena Ronda, Jean Tafforeau, and Sonia Dias. 2017. Migrant’s access to preventive health services in five EU countries. BMC Health Services Research 17: 588. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2549-9.

Singh, Girish K., and Mohammad Siahpush. 2001. All-cause and cause-specific mortality of immigrants and native born in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 91: 392–399. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.3.392.

Szczepura, Ala. 2005. Access to health care for ethnic minority populations. Postgraduate Medical Journal 81: 141–147. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2004.026237.

Taylor, Stephanie L., and Nicole Lurie. 2004. The role of culturally competent communication in reducing ethnic and racial healthcare disparities. The American Journal of Managed Care 10: SP1–SP4.

Topel, Marta F. 2012. Jewish orthodoxy and its discontents: Religious dissidence in contemporary Israel. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Velan, Baruch, and Ronit Pinchas-Mizrachi. 2019. Health concerns of young Israelis moving from the ultra-orthodox to the secular community: Vulnerabilities associated with transition. Qualitative Research in Medicine and Healthcare 3: 32–39. https://doi.org/10.4081/qrmh.2019.8051.

Wafula, Edith Gonzo, and Shedra Amy Snipes. 2014. Barriers to health care access faced by Black immigrants in the US: Theoretical considerations and recommendations. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 16: 689–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-013-9898-1.

Wallace, Matthew, and Hill Kulu. 2014. Low immigrant mortality in England and Wales: A data artefact? Social Science & Medicine 120: 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2014.08.032.

Wallace, Matthew, and Hill Kulu. 2015. Mortality among immigrants in England and Wales by major causes of death, 1971–2012: A longitudinal analysis of register-based data. Social Science & Medicine 147: 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2015.10.060.

Funding

The study was funded by the Israel Academic College in Ramat Gan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pinchas-Mizrachi, R., Velan, B. The Effects of Sociocultural Transitioning on Accessibility to Healthcare: The Case of Haredi Jews Who Leave Their Communities. Cont Jewry 42, 139–156 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-022-09433-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-022-09433-2