Abstract

Introduction

Management of patients with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) can exert a substantial burden upon caregivers. As new modes of treatment administration are developed, it is important to assess caregiver satisfaction and preference in a standardized manner. This study describes the development of the Alzheimer’s Disease Caregiver Preference Questionnaire (ADCPQ) to assess AD caregivers’ satisfaction with and preference for patch or capsule treatments in AD patients.

Methods

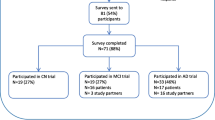

Twenty-five published articles (1987-2002) were reviewed to identify potential ADCPQ domains. Three caregiver focus groups (n=24) were conducted to develop a first draft of the questionnaire. After evaluating the acceptance of ADCPQ to caregivers through in-depth interviews (n=10), its psychometric properties were assessed using data from 986 patients enrolled in a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, four-arm, placebo- and active-controlled, 24-week trial.

Results

Focus groups indicated that caregivers expressed dissatisfaction with current AD treatment routines including limitations related to: efficacy, administration schedule, number of pills, adherence to treatment, side effects, and taking pills. In-depth interviews with caregivers found the ADCPQ to be comprehensible with an acceptable layout. The resultant ADCPQ comprises three modules: A) baseline, 11 items assessing treatment expectations; B) week 8, 33 items on satisfaction and preferences with treatment options; C) week 24, 10 items assessing overall opinions of treatment options. Missing data per item was low (≤0.3%) and domain internal consistency reliability was good (0.71–0.91). Preference items were also valid when evaluating concordance and discordance between convenience and satisfaction patch and capsule domain scores.

Conclusion

AD treatment puts a significant strain on caregivers. New modes of treatment delivery may be less burdensome to caregivers, thereby increasing satisfaction and potential treatment adherence. The ADCPQ was well accepted by AD caregivers and its domains demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties. The ADCPQ is a useful tool to understand caregiver preferences for patch versus oral therapies in AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Croog SH, Burleson JA, Sudilovsky A, Baume RM. Spouse caregivers of Alzheimer patients: problem responses to caregiver burden. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10:87–100.

Donaldson C, Tarrier N, Burns A. Determinants of carer stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13:248–256.

Takechi H, Yamada H, Sugihara Y, Kita T. Behavioral and psychological symptoms, cognitive impairment and caregiver burden related to Alzheimer’s disease patients treated in an outpatient memory clinic [in Japanese]. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2006;43:207–216.

Sink KM, Covinsky KE, Barnes DE. Caregiver characteristics are associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:796–803.

Mahoney R, Regan C, Katona C. Anxiety and depression in family caregivers of people with Alzheimer disease: the LASER-AD study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:795–801.

Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims [draft guidance]. FDA web site. February 2006. Available at: www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/5460dft.pdf. Accessed June 2006.

Boyd MA. Psychiatric Nursing: Contemporary Practice. 3rd edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004.

Travis SS, Kao HF, Acton GJ. Helping family members manage medication administration hassles. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2005;2005:13–15.

Slattum PW, Johnson MA. Caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Consult Pharm. 2004; 19:352–362.

Valle-Jones C, O’Hara J, O’Hara H. Comparative clinical trial of the tolerability, patient acceptability and efficacy of two transdermal glyceryl trinitrate patches (’Deponit’ 5 and ‘Transiderm-Nitro’ 5) in patients with angina pectoris. Curr Med Res Opin. 1989;11:331–339.

Allan L, Hays H, Jensen NH, et al. Randomised crossover trial of transdermal fentanyl and sustained release oral morphine for treating chronic non-cancer pain. BMJ. 2001;322:1154–1158.

Baker VL. Alternatives to oral estrogen replacement. Transdermal patches, percutaneous gels, vaginal creams and rings, implants, other methods of delivery. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1994;21:271–297.

Branche GCJr., Batts JM, Dowdy VM, Field LS, Francis CK. Improving compliance in an innercity hypertensive patient population. Am J Med. 1991;91:37S–41S.

Burris JF, Papademetriou V, Wallin JD, Cook ME, Weidler DJ. Therapeutic adherence in the elderly: transdermal clonidine compared to oral verapamil for hypertension. Am J Med. 1991; 91:22S–28S.

Burris JF. The USA experience with the clonidine transdermal therapeutic system. Clin Auton Res. 1993;3:391–396.

Donner B, Zenz M. Transdermal fentanyl: a new step on the therapeutic ladder. Anticancer Drugs. 1995;6(suppl. 3):39–43.

Jeck T, Edmonds D, Mengden T, et al. Betablocking drugs in essential hypertension: transdermal bupranolol compared with oral metoprolol. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1992;12:139–148.

Parker S, Armitage M. Experience with transdermal testosterone replacement therapy for hypogonadal men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999;50:57–62.

Payne R, Mathias SD, Pasta DJ, Wanke LA, Williams R, Mahmoud R. Quality of life and cancer pain: satisfaction and side effects with transdermal fentanyl versus oral morphine. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1588–1593.

Martens M. Efficacy and tolerability of a topical NSAID patch (local action transcutaneous flurbiprofen) and oral diclofenac in the treatment of softtissue rheumatism. Clin Rheumatol. 1997;16:25–31.

Utian WH. Transdermal estradiol overall safety profile. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:1335–1338.

Wong JO, Chiu GL, Tsao CJ, Chang CL. Comparison of oral controlled-release morphine with transdermal fentanyl in terminal cancer pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 1997;35:25–32.

Lake Y, Pinnock S. Improved patient acceptability with a transdermal drug-in-adhesive oestradiol patch. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;40:313–316.

Riley S, Morris B, Walker L, Reese P, White L. Comparison of two transdermal nitroglycerin systems: Transderm-Nitro and Nitro-Dur. Clin Ther. 1992;14:438–445.

Radbruch L, Sabatowski R, Elsner F, Loick G, Kohnen N. Patients’ associations with regard to analgesic drugs and their forms for application — a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2002; 10:480–485.

Gomez-Panzani E, Williams MB, Kuznicki JT, et al. Application and maintenance habits do make a difference in adhesion of Alora transdermal systems. Maturitas. 2000;35:57–64.

Reddington C, Cohen J, Baldillo A, et al. Adherence to medication regimens among children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:1148–1153.

Donner B, Zenz M, Tryba M, Strumpf M. Direct conversion from oral morphine to transdermal fentanyl: a multicenter study in patients with cancer pain. Pain. 1996;64:527–534.

Ahmedzai S. New approaches to pain control in patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1997; 33(suppl. 6):S8–S14.

Ahmedzai S, Brooks D. Transdermal fentanyl versus sustained-release oral morphine in cancer pain: preference, efficacy, and quality of life. The TTS-Fentanyl Comparative Trial Group. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:254–261.

Lopes P, Rozenberg S, Graaf J, Fernandez-Villoria E, Marianowski L. Aerodiol versus the transdermal route: perspectives for patient preference. Maturitas. 2001;38(suppl. 1):S31–S39.

Hollister L, Gruber N. Drug treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Effects on caregiver burden and patient quality of life. Drugs Aging. 1996;8:47–55.

Howard K, Rockwood K. Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia. 1995;6:113–116.

Steele RG, Anderson B, Rindel B. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive children: examination of the role of caregiver health beliefs. AIDS Care. 2001;13:617–629.

Winblad B, Kawata AK, Beusterien KM. Caregiver preference for rivastigmine patch relative to capsules for treatment of probable Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22: 485–491.

Winblad B, Cummings J, Andreasen N. A 6-month, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of a transxdermal patch in Alzheimer’s disease — rivastigmine patch versus capsule. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:456–467.

Glaser BG, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1967.

Oliver RL. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J Marketing Res. 1980;17:460–469.

Hays R, Hayashi T. Beyond internal consistency reliability: rationale and user’s guide for Multitrait Analysis Program on the microcomputer. Behav Res Methods. 1990;22:167–175.

Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334.

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Chapter 7: The assessment of reliability. In: Psychometric Theory. 3rd edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc.; 1994: 248–292.

Epstein AM, Hall JA, Tognetti J, Son LH, Conant LJ. Using proxies to evaluate quality of life. Can they provide valid information about patients’ health status and satisfaction with medical care? Med Care. 1989;27(suppl.): S91–S98.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abetz, L., Rofail, D., Mertzanis, P. et al. Alzheimer’s disease treatment: Assessing caregiver preferences for mode of treatment delivery. Adv Therapy 26, 627–644 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-009-0034-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-009-0034-5