Abstract

The new idea is to produce specimens by forward rod extrusion, where in the core of the extrudate a deviatoric tension-loading is present, which is superposed by an adjustable hydrostatic pressure. Various damage levels are hence possible in the extrudate. Conducting tensile and upsetting tests with the pre-strained specimens both the influence of a load reversal as well as the material weakening through ductile damage on the resulting flow curve is explored. Not only can the results be utilized to identify flow curves of materials up to high strains (ε > 1.7), but also to get new insights into the plastic material behaviour, which can be used for generating or adapting new damage models as well as kinematic hardening models under cold forging conditions. The proposed method was first assessed by means of analytical and numerical methods and then validated experimentally, by the example of the typical cold forging steel 16MnCrS5.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The flow curve is the relation between the flow stress and the true plastic strain. In the field of metal forming, flow curves are necessary for the prediction of forming forces, tool deflection, material flow as well as the resulting product properties of the produced parts. According to Bridgeman [1] the formability of metals increases significantly under hydrostatic pressure. Since in cold forging, the hydrostatic pressure is usually large, a high variety of complex part geometries can be produced. In order to predict the plastic material behaviour under cold forging conditions by means of numerical analyses with sufficient accuracy, the flow curve needs to be defined up to the large strains that actually occur during the forming process.

For bulk materials, the most common experimental methods used to determine flow curves are tensile tests, upsetting tests and torsion tests. In the case of tensile tests the maximum plastic strain is given by the onset of necking, when the true strain ε is equal to the corresponding hardening exponent n of the workpiece material. After necking the material plastically deforms further but in an inhomogeneous manner, which makes the evaluation of the flow stress difficult. Several authors have tried to take into account the plastic flow in the post-necking regime. Bridgman [2] and Mirone [3] have achieved this by means of analytical descriptions of the post-necking geometry, while other authors like Kajberg and Lindkvist [4] and Kim et al. [5] focused on the use of inverse methods based on tracking and modelling the evolution of the displacement field during deformation of the tensile specimens. Latter publication gives a good overview of methods to characterize the strain hardening behaviour in the post-necking regime. In upsetting tests, a cylindrical specimen is compressed between two parallel dies. The limit for flow curve evaluation is given by the occurrence of barrelling, caused by the friction between the dies and the specimen. In the torsion test a cylindrical bar or pipe is twisted. The main difficulty here, is to calculate representative shear stress and shear strain from experimental data, due to the statically indeterminate nature of the process.

Usually, the actual strains achieved in cold forging processes drastically exceed the strains reached by the conventional experimental methods. To estimate the flow stresses of metals for higher strains, several equations have been proposed to extrapolate the measured flow stresses from experimentally measured results (Fig. 1). Due to the lack of experimental data in the higher strain regions, the choice of the best extrapolation model is difficult and often leads to large uncertainties.

For sheet metals, various experimental methods have been proposed to evaluate flow curves up to large strains. Steglich et al. [10] conducted compression tests on stacked magnesium sheets produced by rolling and extrusion. Coppieters and Kuwabara [11] used an inverse approach as well as the uniaxial tube expansion test in order to quantify the strain hardening of cold rolled interstitial-free steel in the post-necking regime. Tekkaya and Pöhlandt [12] have reached true strains up to ε = 0.9 by means of the in-plane torsion test (Fig. 2). More recent investigations of the in-plane torsion test by Traphöner et al. [13] focus on the use of grooved specimens and optical strain measurement in order to evaluate accurate flow curves to even higher true strains.

Most experimental methods for flow curve evaluation of sheets cannot be used for the characterization of bulk materials. Due to the simple experimental setup of upsetting tests, the process was investigated and developed further by many authors. Various methods have been proposed to minimize the influence of friction by means of additional experimental precautions. These precautions usually deal with the use of special specimen geometries, e.g. the use of lubrication pockets, as proposed by Rastegaev [14]. Siebel and Pomp [15] utilize specimens with conical end faces in order to compensate the frictional stresses. For this, several tests must be conducted with varying point angles of the conical dies to reach an optimal friction compensation. By the use of special specimen geometries, strains up to ε = 1.0 are possible for some materials. For higher strains up to ε = 2.0, the plane strain upsetting test is often utilized, as proposed by Nadai [16] and further developed by Orowan [17] and Watts and Ford [18]. In the plane strain upsetting test, a flat specimen is compressed between two narrow punches (Fig. 3). By the choice of a high relation between specimen width and thickness a nearly plane-strain deformation can be reached. However, due to large frictional forces, the flow stress is usually overestimated significantly in the plane strain upsetting test.

Plane-strain upsetting test (adapted from Nadai [10])

All of the before-mentioned methods for flow curve evaluation are either strictly limited by the maximum amount of plastic strain or include uncertainties regarding the actual stress and strain distributions within the specimen. Reicherter [19], Siebel [20] and Sachs [21] have taken into account the friction-related stresses in upsetting tests by means of analytical models based on the mechanics of the process. While a certain improvement of the flow curves is possible by mathematical methods, additional uncertainties arise, regarding the underlying friction models and the unknown specimen geometry due to barrelling. Pöhlandt et al. [22] have proposed a method to calculate a critical surface distance in torsion tests, to improve the estimation of the shear strain.

Summaries of experimental procedures for flow curve evaluation in bulk forming are given, e.g. by Krause [23], Nebe and Stenger [24], Pöhlandt [25] and Doege et al. [26].

So far, only continuous experimental procedures for flow curve evaluation were presented. Another approach for the evaluation of flow curves for high strains is the conduction of intermittent procedures. Herein, usually the goal is to produce specimens with a large known pre-strain. According to Sevillano et al. [27] it should be stressed that in the utilization of intermittent procedures, the influence of load path changes should be given special care, as changes in the stress state or strain rate may have a significant influence on the work-hardening. The author gives a comprehensive literature review of intermittent procedures for flow curve evaluation. Among these, Langford and Cohen [28] have conducted multi-pass wire-drawing on low-alloyed steel wires in order to pre-strain the material by ε = 0.22 in each pass. By the use of more than 30 passes, the authors were able to reach a total maximum pre-strain of ε ≥ 7. By the conduction of tensile and upsetting tests on the wires, they were able to generate the corresponding flow curve. Pöhlandt [29] has exploited the steady-state properties of forward rod extrusion for the production of pre-strained specimens for the subsequent conduction of upsetting tests for the first time. The author observed large deviations between the results of upsetting tests on undeformed material and its corresponding extrapolation as well as on the specimens pre-strained by forward extrusion. The author suggested, that due to forward rod extrusion, the formed shaft possesses an inhomogeneous strain distribution over the shaft radius which is caused by shearing in the vicinity of the shaft surface, leading to a larger overall flow stress. Doege et al. [26] pointed out that the unusual shape of the resulting flow curves is caused by the Bauschinger effect, due to the load reversal between forward rod extrusion and upsetting. This led the authors to the conclusion that a flow stress evaluation is not possible by the proposed method. Krause [23] utilized rolling to produce sheets with known pre-strains in order to find the flow curves by subsequent tensile tests on the pre-strained specimens leading to flow curves up to high strains. However, large deviations were observed in a comparison with results of conventional testing methods. Possible reasons for these deviations will be discussed in the following.

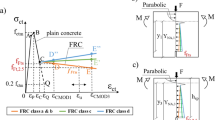

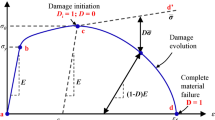

Besides strain hardening, materials are subjected to additional phenomena during forming, which can affect the global flow stress. While strain hardening results from the restrained movement and generation of dislocations, plastic deformation may lead to the nucleation, growth and coalescence of voids, regarded as ductile damage [30]. The accumulated damage may lead to a weakening of the material due to a decrease of the load bearing cross-section. The amount of accumulated damage generally depends on the stress state the material is subjected to. Behrens and Landgrebe [31] explain the flow stress difference under tensile and compressive loading by the evolution of damage in a tensile test. The authors utilize the difference in the flow curves to illustrate the evolution of ductile damage. The damage is quantified by the damage variable D, which is an indicator for the volume fraction of voids as compared to the volume of the surrounding metal matrix (Fig. 4).

Illustration of evolution of damage variable D in tensile and compressive tests (adapted from Behrens and Landgrebe [31])

In addition to damage, a plastic load reversal leads to a direction dependence of the flow stress due to the Bauschinger effect. As a consequence, both damage and the Bauschinger effect must be considered in the evaluation of flow curves for large strains, especially for intermittent experimental procedures.

Forward rod extrusion is a unique process to produce cylindrical parts with large known pre-strains. The amount of plastic strain along the central axis of the extrudate is directly prescribed by the reduction of the cross-section. To the knowledge of the authors of this paper, no publication exists, which deals with the conduction of tensile tests on material pre-strained by forward rod extrusion to characterize the plastic behaviour of metals under large plastic strains. So far, the highest strains were reached by Langford and Cohen [28] utilizing wire-drawing. In wire-drawing, the maximum strain per pass is highly limited by the occurrence of necking. This, however, does not apply in forward rod extrusion, as the material is pushed through the die under high compressive stresses. In addition to this, forward rod extrusion allows for the extraction of standardized specimens for the conduction of subsequent tests, which means the influence of inhomogeneous strain distribution can be incorporated more accurately.

The aim of this paper is the systematic evaluation of flow curves for high strains by tensile and upsetting tests on specimens pre-strained by forward rod extrusion (Fig. 5a). The flow stress of pre-strained specimens can then be used, as support points in the generation of flow curves up to high strains (Fig. 5b).

In a first step, the process sequence is investigated analytically and numerically in order to evaluate whether a production of pre-strained specimens is possible with the following necessary requirements:

Homogeneous strain distribution over specimen length

Known strain distribution over specimen radius

Monotonic stress history for material points moving through the forming zone

Negligible residual stresses within specimens.

The requirements have been verified for standardized tensile and upsetting test specimens (diameter d = 8 mm).

In a second step, the proposed method was utilized on 16MnCrS5 case-hardening steel in order to evaluate the corresponding flow curve as well as to assess the influence of hydrostatic pressure during forward extrusion as well as a load reversal on the resulting flow stress.

Characteristics of forward rod extrusion

Fundamental parameters

Forward rod extrusion is a cold forging process, where a (usually) cylindrical workpiece is pushed through a conical die, which leads to a reduction of the cross-section. For large cross-section reductions, the workpiece is surrounded by a container to limit upsetting (Fig. 6).

The process can be characterized by the initial workpiece diameter d0, the die shoulder opening angle 2α and the diameter of the formed extrudate diameter d1. From volume constancy it follows that the strain along the rotational axis of the extrudate can be calculated exactly as

where A0 and A1 are the cross-section areas of the workpiece and the extruded shaft, respectively. In the following, the local effective strain or true strain ε will be separated from the extrusion strain εex by the index. Along its central axis the pre-strain εpre of a cylindrical specimen extracted from an extruded rod, is equal to the corresponding extrusion strain εex. In order to reach a prescribed strain along the central axis of the workpiece, the inner diameter of the die cavity d1, which directly prescribes the resulting shaft diameter of the extrudate, is given by:

Strain distribution over extrudate length

A necessary requirement for the production of pre-strained specimens by forward extrusion is a homogenous strain distribution over the specimen length. An inhomogeneous strain distribution would lead to a inhomogeneous stress distribution in the tensile test specimens during loading, which may cause premature necking. After necking the calculation of the corresponding flow stress from the tensile force is impossible.

After upsetting of the workpiece in the container the material begins to flow through the die opening. A steady-state process state is reached, which leads to a constant strain distribution along the produced shaft. The material flow during forward extrusion can be illustrated experimentally by means of visioplastic methods. For this, two marked half sections are extruded together and the distorted markings after forming are visualised (Fig. 7). The existence of a steady-state region between the shaft tip and the die shoulder becomes obvious.

Material flow in forward rod extrusion (εex = 1.0, 2α = 120°, adapted from Ossenkemper [32])

The resulting strain distribution over the shaft radius was further investigated by means of numerical analysis. A detailed description of the numerical model of forward extrusion by means of FEM are documented in Appendix A. Contour plots of the overall effective strain distribution are shown for extrusion strains of εex= 0.5 (39% area reduction), εex= 1.0 (63%) and εex= 1.5 (78%) (Fig. 8).

The numerical results emphasize, that due to the steady-state properties of forward extrusion, the strains are homogeneously distributed over a sufficiently large region of the extrudate length. For a standardized tensile test specimen with a diameter d = 8 mm and a total length of l = 77 mm (DIN 50125 – B 8 × 40) the strains are homogenous over the whole specimen length, which means the first requirement is fulfilled.

Strain distribution over extrudate radius

From Fig. 7 and 8 the inhomogeneous distribution of the true strain over the extrudate radius becomes clear. The second requirement for the produced specimens is a known strain distribution over the specimen radius. The knowledge of the strain distribution allows for a definition of an effective strain, which can be used to shift flow curves of pre-strained material by a known pre-strain.

Figure 9 shows a comparison of the effective local strain and the results of macro-hardness measurements over the radius of an extrudate with εex = 0.5. A correlation between hardness and effective strains exists, which has been thoroughly investigated in the literature, e.g. by Tekkaya and Lange [33]. Within the centre of the extrudate, the effective strain and the hardness are nearly constant, whereas they show a progressive increase toward the shaft surface.

Figure 10 summarizes the numerically determined effective strain distribution over the corresponding squared shaft radius, for the corresponding extrusion strains. The squared shaft radius is proportional to the cross-section area.

Along the central axis of the produced shafts, the local effective strain is slightly higher than the extrusion strain εex calculated by Eq. 1. The deviation comes from the strain resulting from upsetting of the workpiece in the container, differences in the elastic expansion of the container and the die as well as numerical inaccuracies caused by remeshing. The error amounts to less than 2.8% for all investigated extrusion strains. Towards the shaft surface, the effective strains increase due to shearing, whose amount depends on the friction conditions, the tool radii and the semi-cone angle of the die. Within the region of specimen extraction with a diameter of 8 mm (squared radius of 16 mm2), the effective strain increases in a linear fashion. In order to take into account the increasing strains within the extracted specimens, an area-weighted average strain \( \overline{\varepsilon} \) was defined as the mean strain over the squared radius within the extraction region. In Fig. 10, the area-weighted strains are indicated by the dashed horizontal lines. The maximum error between the area-weighted strain and the actual effective strain is present for the highest extrusion strain of εex= 1.5 and amounts to 7%. Figure 11 shows a comparison of the ideal extrusion strains (Eq. 2) and the area-weighted average strains \( \overline{\varepsilon} \). It can be observed, that \( \overline{\varepsilon} \) increases linearly with increasing extrusion strain εex, however, the values are consistently higher than the extrusion strains.

From the deviation of the area-weighted average strains and the actual strain distribution of pre-strained specimens (Fig. 10) the question arises, whether a flow curve evaluation is possible with sufficient accuracy, although the local effective strain during tensile loading is unknown. To investigate this, simulations of tensile tests were conducted, considering specimens with the actual pre-strain distribution generated by forward extrusion as well as specimens homogeneously pre-strained by the area-weighted average strain \( \overline{\varepsilon} \) (Appendix B). As a result of the investigations, the strain inhomogeneity over the specimen radius is taken into account in the flow curve evaluation procedure by shifting the flow curves of the pre-strained specimens by the corresponding amount of area-weighted average strain \( \overline{\varepsilon} \).

Load path

In general, the flow stress of a pre-strained material depends on the stress history that previously led to its deformation. While ductile damage can result in a reduction of the flow stress of pre-strained material, the Bauschinger effect introduces a direction dependence of the flow stress. In the case of tensile tests on rolled sheets Krause [23] observed lower flow stresses in comparison to conventional methods, i.e. tensile and upsetting tests. To account for this, the stress states during forward extrusion are investigated and compared to the stress states of tensile tests.

In order to determine the evolution of the stress states along the central axis in forward rod extrusion, the increments of strain dεij are considered first. If the coordinate system is chosen according to Fig. 12, the strain increments can be defined in the three principal directions r, z and t.

Along the central axis no shear stresses exist. Following from this, the components of the tensor of strain increments in a material point on the central axis is given as

From axisymmetry, it follows that the strain increments on the rotational axis in the radial and circumferential direction must be equal (dεr = dεt), which leads to

Due to the volume constancy of plastic deformations, the sum of the principal strain increments must vanish:

The contraction of the cross-sectional area leads to dεr = dεt < 0 and hence by Eq. 6dεz = − 2dεr > 0 it follows

In forward rod extrusion, the stress component in the axial direction is always the algebraically largest. It follows for the principal stress components that

The stress components can be subdivided into their deviatoric and hydrostatic parts \( {\sigma}_{ij}^{\prime } \) and σhij, respectively. The hydrostatic stress reads

By subtracting the hydrostatic stress from the total stress tensor, the deviatoric stress components read

Under the assumption of an isotropic flow condition (e.g. von Mises or Tresca) the flow stress σf along the central axis is given by

By insertion of Eq. 11 into Eq. 9 and Eq. 10 the hydrostatic stress and deviatoric stress components are reformulated to

The deviatoric stress \( {\sigma}_{ij}^{\prime } \) is related to the strain increments dεij by the Levy-Mises flow rule:

where dλ is the plastic multiplier, a non-negative real number.

In comparison to forward rod extrusion, the stress components for simple tension read

With σz = σf, the hydrostatic stress and deviatoric stress components yield

Hence by comparison of Eq. 13 and Eq. 17, forward extrusion yields the same deviatoric stress state along the rotational axis of the extrudate as the uniaxial tensile test. Both stress states differ only by the amount of radial stress σr in the hydrostatic stress (Eq. 12 and Eq. 16). Usually, σr is large in forward rod extrusion. Due to the large resulting hydrostatic pressure supressing damage, a high material formability is possible, which, for some materials, allows for large true strains of 1.6 and higher.

Thorough investigations have been conducted e.g. by Avitzur et al. [34] to predict the stresses occurring in the forming zone during forward rod extrusion by means of the upper-bound method. However, the exact amount of hydrostatic stress cannot be predicted analytically with sufficient accuracy, making the use of numerical methods necessary.

Description of loading conditions by triaxiality and Lode parameter

Under the assumption of plastic flow, any three-dimensional stress state can be described by two scalar values, namely the stress triaxiality η and the Lode parameter \( \overline{\theta} \). The stress triaxiality is defined by

where σvM is the von Mises effective stress and σh the hydrostatic stress. According to Bai and Wierzbicki [35] η can be referred to as the dimensionless hydrostatic pressure. The Lode parameter \( \overline{\theta} \), is defined by

Herein, σ1, σ2 and σ3 again indicate the first and second and third principle stresses.

Since the Lode parameter is connected to the deviatoric part, it is required to be equal for both tensile tests as well as forward rod extrusion. Figure 13 shows that in the vicinity of the central axis \( \overline{\theta}= \) 1, which is also fulfilled for tensile tests on round bars.

In a tensile test, the stress triaxiality, which describes the hydrostatic part of the stress state, is always η = 1/3. However, in forward rod extrusion the stress triaxiality is not constant and strongly depends on the extrusion parameters. The influence of the extrusion strain on the stress triaxiality is shown in Fig. 14.

The evolution of the stress triaxiality over the effective strain along the central line is shown in Fig. Figure 15 for three extrusion strains. First, the triaxiality is negative, due to upsetting in the container. Upon entry of the forming zone the triaxiality increases until reaching its peak value ηmax in the centre of the forming zone. With increasing extrusion strain εex, the triaxiality curves are increasingly translated into the negative region.

In order to quantify the hydrostatic stress states, the evolution of the stress triaxiality has been computed by two approaches. In utilizing

it is assumed, that the the maximum stress triaxiality is representative for the evolution of damage and thus for the macroscopic flow stress change. Herein, it is presumed, that pores can only nucleate, but not shrink. On the contrary, the “strain-weighted stress triaxiality”

additionally takes into account the increments of plastic strain dε along the central axis in combination with the corresponding triaxiality.

The two definitions of triaxiality measures will help to characterize the stress history a material point along the central axis has been subjected to during extrusion. Table 1 shows the two evaluated triaxiality measures depending on the investigated extrusion strains.

In the case of ηmax an extrusion strain of εex = 0.3 leads to a maximum triaxiality of ηmax = 1/3, which corresponds to the stress state of uniaxial tensile test. For \( \overline{\eta} \) the corresponding value lies between extrusion strains of εex = 0.1 and εex = 0.3. Up to extrusion strains of εex = 0.7, the triaxiality values are above or close to zero. For both triaxiality measures a further increase of the extrusion strain leads to a progressive shift towards negative triaxiality values, which makes the evolution of damage highly unlikely for larger extrusion strains.

Since extracted specimens from the extrudate do not only contain material particles which have moved along the central line during forward extrusion, the maximum stress triaxiality ηmax was calculated for various material lines over the specimen radius (Fig. 16).

The maximum stress triaxiality values along the centre lines from Table 1 are indicated in the diagram at a radius of r = 0 mm. With increasing radius the maximum triaxiality tends to decrease toward the specimen surface. This holds for all extrusion ratios up to εex= 1.0. For higher extrusion strains, the curves flatten. Though the maximum stress triaxiality is not constant over the specimen radius, no intersections are present for the lines corresponding to varying extrusion strains. Hence, the triaxiality values calculated in Table 1 are sufficient to compare the stress history of extrudates by the use of just one characteristic value such as ηmax(r = 0).

Residual stresses

Cold forging can lead to high forming induced residual stresses, caused by inhomogeneous elastic-plastic deformations. To isolate the influence of forming induced residual stresses from the resulting flow stress, a numerical analysis has been performed to evaluate the residual stresses in the test specimens after extraction by machining.

First the residual stress distribution before and after ejection of the part was investigated. The stress distribution is shown for εex = 0.5 (Fig. 17).

After extrusion and before ejection, the formed part contains large residual stresses which are caused by inhomogeneous plastic deformations during cold forging. Small plastic deformations during the ejection process lead to a significant drop of residual stresses, which is documented and explained in the literature e.g. by Tekkaya and Gerhardt [36]. The numerically evaluated residual stress distribution after ejection is depicted in Fig. 18 for an extrusion strain of εex = 0.5. For this investigation, the conventionally obtained flow curve (upsetting test up to ε = 0.7) was used.

While the core of the part is subjected to compressive stresses of 50% of the initial flow stress of the annealed material σf, 0 = 340 MPa, the stress increases toward the shaft surface, resulting in a positive stresses of 25% of σf, 0 in this region. After extraction of a cylindrical specimen (diameter d = 8 mm) by turning, the self-equilibrating nature of residual stresses leads to a second drop, as the region containing large positive stress is removed. The residual stresses after turning were evaluated analytically by shifting the remaining part of the curve to zero, in order to reach a stress balance. The remaining residual stresses are within the small range of ±50 MPa (±14.7% of σf, 0). Since in this procedure it is assumed that the turning operation does not cause additional residual stresses, the results are an approximation of the actual stress distribution.

Experimental procedure

It was shown, that a production of cylindrical specimens from forward extruded rods with a known pre-strain is possible. In the following, the experimental procedure to produce and test the pre-strained specimens to achieve flow curves up to high strains is presented and the results are discussed.

Cold extrusion

All experiments were performed on a hydraulic triple action drawing press SMG HZPUI 260/160–1000/1000 with a maximum force of 2600 kN and a punch speed of 10 mm/s at room temperature. All billets were lubricated with Beruforge 191 by manufacturer Carl Bechem GmbH. Beruforge 191 is a MoS2, containing coating lubricant with small particle size for temperatures up to 500 °C, for the application on non-phosphated semi-finished products. The billets were extruded up to a constant shaft length of 80 mm. The semi-cone angle of the die and the transition radii were kept constant for all investigations (2α = 90°, r = 3 mm). The initial diameter of the semi-finished parts was d0 = 30 mm, the initial workpiece length l0 = 71 mm. The investigated extrusion strains and corresponding reduced diameters are summarized in Table 2.

The case-hardening steel DIN 16MnCrS5 (SAE 5115) was used for all investigations. Table 3 shows the chemical composition of the case-hardening steel.

The initial workpiece as well as the forward extruded rods with varying extrusion strains are shown in Fig. 19.

From the extruded rods, tensile and upsetting test specimens were extracted by means of turning. Details on the specimen extraction and the testing procedures will be discussed in the following.

Tensile tests

Tensile tests were conducted on a Zwick Roell Z250 universal testing machine up to fracture on specimens machined from annealed material as well as on specimens pre-strained with varying extrusion strains according to Table 2. The position of extraction as well as the specimen geometry (DIN 50125 – B 8 × 40) is shown in Fig. 20.

All tensile tests were conducted according to DIN EN ISO 6892-1. The velocity was controlled in order to ensure a constant strain rate of 0.0067 s−1. The specimen elongation was measured directly on the test specimens by means of a tactile macro-extensometer with a gauge length of 40 mm.

Upsetting tests

Upsetting tests were conducted on specimens machined from annealed material as well as on pre-strained specimens. The position of extraction as well as the specimen geometry is shown in Fig. 21.

The upsetting tests were conducted according to DIN 50106, with a constant strain rate of 0.0067 s−1. In order to reduce the friction between the test specimens and the dies, the contacting surfaces were sprayed with Teflon spray after each upsetting test. The change in height of the specimen was measured indirectly by the crosshead travel. To account for the unavoidable elastic deflection of the testing machine a stiffness correction curve was utilized. The recorded values were validated against the actual deformed specimen heights after upsetting, whereby only small deviations of ±2% were observed.

Results and discussion

The procedure of flow curve evaluation for large strains by means of tensile tests on material pre-strained by forward rod extrusion will be discussed in the following. In addition, the variation of the extrusion strain εex allowed for an investigation of the influence of hydrostatic pressure on the resulting flow curves. In order to evaluate the forming induced Bauschinger effect a comparison of tensile and compressive flow curves of the pre-strained material was conducted.

True stress-strain curves were calculated from the force and stroke measurements of the tensile and upsetting tests (Fig. 22). Each test was repeated least three times. For every test set the median curve was chosen. For a given strain the deviation in stress between the median curve and the other curves of the corresponding set was always less than 1%.

The dark red curve corresponds to the result of the tensile test on annealed material. The specimens necked at true strains of approximately ε = 0.12. The dark blue curve, corresponding to the result of the upsetting test on annealed material, was evaluated up to a strain of ε = 0.7. After that, barrelling of the specimen due to friction became too pronounced for a correct calculation of the true stress, noticeable by a discontinuity in the flow curve. The true stress-strain curves of the tensile and upsetting tests on material pre-strained by forward rod are plotted as bright red and blue lines, respectively. The beginning of each pre-strained curve was shifted by their corresponding area-weighted pre-strain \( \overline{\varepsilon} \), as explained in the previous section (Fig. 11).

So far, no special emphasis was given to the change in strain rate between extrusion and subsequent tensile and upsetting tests. However, Fig. 22 suggests that the change in strain rate does not have a significant influence on the work-hardening behaviour of the material, as the tensile and compressive flow curves of extruded material are consistently lower than the flow curves of annealed material. This is underlined by results from Doege et al. [26], where no significant strain rate sensitivity was observed for strain rates below 8 1/s. Following from these observations, the strain rate sensitivity of the flow curves was neglected in the subsequent investigations.

Flow curve evaluation

A deviation exists between the flow curve from the upsetting test on annealed material and the flow curves from tensile tests on pre-strained material. One possible explanation for the deviation is related to friction in upsetting, which eventually leads to the unfavourable barrelling of the specimen. Additional friction forces must be overcome to initiate yielding of the material, resulting in a higher overall upsetting force and thus, in a higher apparent flow stress. In order to take into account the inhomogeneous stress distribution resulting from friction, the friction-corrected flow stress σf, μ was calculated according to Siebel [20] :

Herein, F is the experimental upsetting force and D and h are the current diameter and height of the deformed specimen, respectively. The Coulomb-friction coefficient is symbolized by μ. According to Eq. 22 the influence of friction on the apparent flow stress becomes more pronounced with a decrease in the height to diameter ratio, since the contact surface increases in a quadratic manner with decreasing specimen height.

Figure 23a shows a comparison of the friction-corrected upsetting flow curve for friction coefficients of μ = 0.05 and μ = 0.1. By the use of a friction coefficient of μ = 0.05 the compressive flow curve is lowered onto the “friction-free” tensile flow curve of the annealed material. The decrease of the calculated flow stress leads to a general reduction of the deviation between the compressive flow curve on annealed material and tensile flow curves of pre-strained material. A further increase of the friction coefficient to μ = 0.1 leads to an underestimation of the friction-free tensile flow stress, which is not admissible. Consequently, the friction coefficient of μ = 0.05 was used for the friction-correction. The remaining deviation between the friction-corrected compressive flow curve and the tensile flow curve indicates that friction only contributes partly. The second part of the deviation is assumed to be caused by forming induced damage in the pre-strained specimens, which is dealt with in the next section.

A flow curve was generated by use of the data from the friction-corrected upsetting test on annealed material (μ = 0.05). The maximum stress of the tensile flow curve of the specimen pre-strained by εex = 1.5 was used as an additional support point, acting as a lower bound for the flow curve at the corresponding area-weighted average strain \( \overline{\varepsilon} \) = 1.67. Due to its low number of model parameters, the Swift-type flow curve model was utilized according to

C, ε0 and n are model parameters corresponding to a scaling in stress, a shift in strain and the hardening exponent, respectively. Due to the larger number of data points in the upsetting test regime, the support point was given more weight to be considered by the optimization algorithm. Generally, the choice of the flow curve model is arbitrary, as long as the model is capable to capture the experimental data with sufficient accuracy. In Fig. 23b, the resulting flow curve extrapolation is shown as dashed green line.

Damage

The remaining deviation between the compressive flow curve of annealed material and the tensile flow curves of pre-strained material suggests that the variation of hydrostatic stress superposition during extrusion affects the strain hardening behaviour. In the second section, it was shown that the amount of hydrostatic stress along the central axis of a forward rod extruded shaft depends on the extrusion strain. The influence of hydrostatic and deviatoric stresses on the evolution of ductile damage is the topic of several ongoing research projects. Generally, it is assumed that for a given constant Lode parameter a high triaxiality may lead to an evolution of ductile damage, causing a material weakening, while negative triaxiality values tend to cause little or no damage accumulation.

Figure 24 shows the maximum hydrostatic pressure as well as the corresponding maximum triaxiality in the forming zone, as a function of the extrusion strain. Up to an extrusion strain of εex = 0.7 the hydrostatic stress as well as the triaxiality is above or close to zero. Under these stress states it is generally assumed that ductile damage is accumulated. With increasing extrusion strain, both the hydrostatic stress as well as the triaxiality decrease, eventually resulting in a negative triaxiality, whereby it is assumed that less or no damage is accumulated.

In correspondence to this, Figure 24 shows that the tensile flow curve of annealed material and the tensile flow curves pre-strained up to εex = 0.7 saturate toward a shared flow stress level (black dashed line on the left), which is significantly lower than the “damage-free” compressive flow curve of annealed material (green line). Pre-strains above εex = 0.7 lead to a second flow stress level (black dashed line on the right), which saturates toward the extrapolation of the damage-free compressive flow curve (green dashed line), emphasizing that little or no damage was accumulated in the forward extruded shafts with these extrusion strains.

Tekkaya et al. [37] have found, by means of SEM analysis as well as fatigue testing of specimens made from forward extruded rods that large deviations occur, when extrusion strains of εex = 0.5 and εex = 1.0 are compared. For the lower extrusion strain of εex = 0.5 a more pronounced void nucleation was observed, leading to a significantly lower fatigue strength than the part with εex = 1.0. The influences of work-hardening and residual stress were ruled out by experimental and numerical analyses. The observations are in accordance with the present results regarding the occurrence of triaxiality-dependent flow stress levels of pre-strained specimens.

Load reversal

As shown in Fig. 22, the compressive flow curve of material pre-strained by εex = 0.1 saturates toward an elongation of the compressive flow curve of the annealed material. However, for higher pre-strains, the curves saturate toward lower stress levels. During forward rod extrusion, the material was subjected to a tensile deviatoric stress state, whereas in the upsetting test, the deviatoric stress direction reverses. This load reversal not only leads to a decrease of the yield stress with increasing pre-strain, known as Bauschinger effect, but also to a permanent softening effect, as observed by many authors e.g. Sun and Wagoner [38]. In addition to that, when pre-strains exceed εex = 0.2 a region of work-hardening stagnation becomes apparent. It is stated e.g. by Yoshida und Uemori [39], that the general existence of work-hardening stagnation depends on the investigated material. However, the present results indicate that even when a material does not show a clear region of work-hardening stagnation up to a certain pre-strain, the phenomenon may just be shifted toward larger pre-strain regions. In addition to that, for pre-strains above εex = 0.7, the material seems to show not only one, but two consecutive regions of work-hardening stagnation. The phenomenon becomes more pronounced for higher pre-strains.

Due to the load reversal, the evaluation of upsetting tests on forward extruded material does not suffice for the evaluation of flow curves for large strains. However, a comparison of the tensile and compressive flow curves, give new insights into the Bauschinger effect for materials pre-strained by large true strains over εex = 1.5. In order to evaluate the Bauschinger effect, the Bauschinger coefficient \( {\overline{\sigma}}_y \) is used, which can be defined as the ratio of the yield stresses in opposing load directions according to

Herein, σy,pos and σy,neg are the yield stresses in positive and negative direction. Conventionally, σy,neg is defined as the yield stress under compression and σy,pos the yield stress under tension, respectively. According to Yoshida and Uemori [39], the Bauschinger coefficient depends on the pre-strain εpre. Since the exact identification of the yield point is difficult for pre-strained material, the Rp0.2%-yield-strength is utilized instead. In this paper, the Bauschinger coefficient was evaluated by means of two definitions, considering the tensile yield stress Rp0.2%,tens, the compressive yield stress Rp0.2%,tens of pre-strained material and the flow stress σy, μ. The determination of the three quantities is indicated in Fig. 25a. In the first definition, the Bauschinger coefficient was calculated as the ratio between the tensile and compressive yield stress of pre-strained material, according to

In this definition, the forming induced damage is included in the calculation of the Bauschinger coefficient, since the flow stress Rp0.2 % ,tens is affected by ductile damage accumulated during forward rod extrusion. In the second definition, the flow stress σy, μ is used instead, according to

The evaluated Bauschinger coefficients depending on the corresponding pre-strain reached by forward rod extrusion are shown in Fig. 25b.

For the annealed material, the yield stresses in both load directions are equal which leads to a Bauschinger coefficient of \( {\overline{\sigma}}_{\mathrm{f}} \) = 1. With increasing pre-strain, both Bauschinger coefficients decrease to about \( {\overline{\sigma}}_{\mathrm{f}}= \) 0.6 to \( {\overline{\sigma}}_{\mathrm{f}} \)= 0.7, which means, that the compressive yield stress is about 30–40% lower than the tensile yield stress. Starting from the minimum investigated pre-strain of εpre = 0.1 the Bauschinger coefficients are almost constant for the investigated pre-strains. It is assumed, that the Bauschinger coefficient saturates in a pre-strain region prior to εpre = 0.1, which is true for various materials in the literature. The same method of determining the Bauschinger coefficient can be applied to any associated effect, e.g. permanent softening and transient hardening.

Conclusions

A new experimental method has been proposed to evaluate flow curves of materials by tensile tests on specimens pre-strained by forward rod extrusion. Due to the Bauschinger effect upsetting tests on pre-strained specimens do not suffice for a flow curve evaluation. In addition to this, tensile flow curves with small pre-strains cannot be utilized either, since the strength of these specimens seems to be affected by ductile damage, accumulated during the process of forward rod extrusion. With increasing extrusion strain, however, the stress state is increasingly superposed by hydrostatic pressure, yielding the accumulation of damage unlikely, which means that the resulting curves can be used as support points for a flow curve in the high strain region. The method has been conducted on the case-hardening steel 16MnCrS5, generating a flow curve up to a strain of \( \overline{\varepsilon}= \) 1.7.

Figure 26 illustrates a comparison of the two standard methods of flow curve generation, “tensile test” and “upsetting test”, along with the proposed method “upsetting test and tensile test on extruded specimens” with respect to the maximum strains achievable.

The resulting flow curves and their extrapolation utilizing the three experimental methods are shown in Fig. 27. In the high strain regime there are large deviations between the individual methods. In the present case, the actual flow stress seems to be overestimated drastically when utilizing the commonly used upsetting test, which emphasizes the potential of the use of additional support points.

Since the amount of hydrostatic stress can be varied by changing the extrusion strain in forward rod extrusion, the experimental procedure allows for an investigation of the influence of hydrostatic pressure on the apparent flow stress and thus, a qualitative assessment of ductile damage. In addition, the difference between the tensile and compressive yield stress allows for an evaluation of the Bauschinger effect for pre-strained material. Following from that, the experimental procedure can be used to further develop material models taking into account forming-induced damage and the Bauschinger effect for large pre-strains.

If the strain rate sensitivity or the temperature is of interest the procedure can be adjusted accordingly by changing the extrusion speed or temperature, as well as the tensile test conditions.

References

Bridgman, P W (1952) Studies in large plastic flow and fracture: With special emphasis on the effects of hydrostatic pressure. McGraw-Hill, New York London

Bridgman PW (1944) The stress distribution at the neck of a tension specimen. ASM Trans 236(32):553

Mirone G (2004) A new model for the elastoplastic characterization and the stress–strain determination on the necking section of a tensile specimen. Int J Solids Struct 41(13):3545–3564

Kajberg J, Lindkvist G (2004) Characterisation of materials subjected to large strains by inverse modelling based on in-plane displacement fields. Int J Solids Struct 41(13):3439–3459

Kim JH, Serpantié A, Barlat F, Pierron F, Lee MG (2013) Characterization of the post-necking strain hardening behaviour using the virtual fields method. Int J Solids Struct 50(24):3829–3842

Ludwik P (1909) Elemente der technologischen Mechanik. Berlin

Swift HW (1952) Plastic instability under plane stress. J Mech Physics Solids 1(1):1–18

Voce E (1984) The relationship between stress and strain for homogeneous deformation. J Inst Met 74:537–562

Hockett JE, Sherby OD (1975) Large strain deformation of polycrystalline metals at low homologous temperatures. J Mech Physics Solids 23(2):87–98s

Steglich D, Tian X, Bohlen J, Kuwabara T (2014) Mechanical testing of thin sheet magnesium alloys in biaxial tension and uniaxial compression. Exp Mech 54(7):1247–1258

Coppieters S, Kuwabara T (2014) Identification of post-necking hardening phenomena in ductile sheet metal. Exp Mech 54(8):1355–4371

Tekkaya AE, Pöhlandt K (1982) Determining stress-strain curves of sheet metals in the plane torsion test. CIRP annals – manufacturing. Technology 31(1):171–174

Traphöner H, Clausmeyer T, Tekkaya AE (2017) Material characterization for plane and curved sheets using the in-plane torsion test – an overview. Proceedia Eng 207:1934–1939

Rastegaev MV (1940) Novyj metod ravnomernego osazivanija obrazov dlja opredelenija istennego soprotivlenija deformacii ikoefficienta vnesnego trenija. Zav Labor, p 354

Siebel E, Pomp A (1927) Die Ermittlung der Formänderungsfestigkeit von Metallen aus dem Stauchversuch. Eisenforschung 9:157–171

Nadai A, Wahl M (1931) Plasticity. Mc Graw Hill: New York. In: London

Orowan E (1943) The calculation of roll pressure in hot and cold flat rolling. Proc Inst Mech Eng 150(/52):140–187

Watts AB, Ford H (1955) On the basic yield stress curve for a metal. Proc Inst Mech Eng 169(1):1141–1150

Reicherter, K (1951) Untersuchungen über das plastische Verhalten zylindrischer Proben im Druckversuch. Dissertation TH Stuttgart

Siebel E (1956) Die Bedeutung der Fließkurve bei der Kaltumformung. VDI-Z 98:133–134

Sachs G (1925) Einfluss der Probenhöhe auf den Stauchversuch. Z Metallkunde 16:55–58

Pöhlandt K, Tekkaya AE, Lach E (1983) Testing the plastic behavior of metallic materials by torsions tests. Z Werkstofftechn 13:181–189

Krause U (1963) Comparison of various methods of determining yield stress at room temperature. Stahl und Eisen 83:1621–1640

Nebe G, Stenger H (1963) Zur Aufnhame von Fließkurven an Stahlproben. Materialprüf 6:157–171

Pöhlandt K (1984) Vergleichende Betrachtung der Verfahren zur Prüfung der plastischen Eigenschaften metallischer Werkstoffe. Dissertation Univ, Stuttgart

Doege E, Meyer-Nolkemper H, Saeed I (1986) Fließkurvenatlas metallischer Werkstoffe. Munich, Vienna

Sevillano JG, Houtte P, Aernoudt E (1981) Large strain work hardening and textures. Prog Mater Sci 25:69–134

Langford G, Cohen M (1969) Strain hardening of Iron by severe plastic deformation. Transactions of the ASM 62:623–638

Pöhlandt K (1979) Beitrag zur Aufnahme von Fließkurven bei hohen Umformgraden. Proceedings Neuere Entwicklungen in der Massivumformung, In, pp 1–14

Lemaitre J (1985) A continuous damage mechanics model for ductile fracture. J Eng Mater Technol 107(1):83–89

Behrens A, Landgrebe D (1999) Assessment of deformation sequences using damage mechanics in cold metal forging. Advanced Technology of Plasticity III, In, pp 2311–2316

Ossenkemper S (2018) Verbundfließpressen in konventionellen Fließpresswerkzeugen. Dissertation. TU Dortmund

Tekkaya AE, Lange K (2000) An improved relationship between Vickers hardness and yield stress for cold formed materials and its experimental verification. CIRP Ann Manuf Technol 49(1):205–208

Avitzur B, Narayan C, Chou YT (1982) Upper-bound solutions for flow through conical converging dies. Int J Machine Tool Design Res 22(3):197–214

Bai Y, Wierzbicki T (2008) A new model of metal plasticity and fracture with pressure and lode dependence. Int J Plast 24(6):1071–1096

Tekkaya AE, Gerhardt J, Burgdorf M (1985) Residual stresses in cold-formed workpieces. CIRP Ann Manuf Technol 34(1):225–230

Tekkaya AE, Ben Khalifa N, Hering O, Meya R, Myslicki S, Walther F (2017) Forming-induced damage and its effects on product properties. CIRP annals -manufacturing. Technology 66:281–284

Sun L, Wagoner RH (2013) Proportional and non-proportional hardening behaviour of dual-phase steels. Int J Plast 45:173–187

Yoshida F, Uemori T (2002) A model of large-strain cyclic plasticity describing the Bauschinger effect and work-hardening stagnation. Int J Plast 18(5-6):661–686

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the German Research Foundation (DFG) for the financial support of project A02 in the Collaborative Research Centre CRC/Transregio 188 “Damage Controlled Forming Processes”.

Funding

This study was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), Project A02 in the Collaborative Research Centre CRC/Transregio 188 “Damage Controlled Forming Processes”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

A Simulation model of forward rod extrusion

Homogeneous stress and strain distributions over a sufficiently large region of the forming zone are necessary requirements for the extraction of representative test specimens from the forward rod extruded shafts. In order to evaluate if the requirements are fulfilled for forward rod extrusion, the process was analysed by means of numerical simulations. The use of the method allows for a detailed investigation of the load paths, not only regarding the evolution of stresses and strains along the central axis, but also over the workpiece radius. The simulations were conducted with the FEM-code Simufact.Forming. Due to rotational symmetry, all simulations were conducted with axisymmetric elements.

In the first simulation step, the workpiece is upset within the container by the punch. After filling of the container is reached, the material starts to flow into the die cavity. When a shaft length of 80 mm is reached, the workpiece is unloaded and pushed out of the die by an ejector. The workpiece was modelled elastic-plastic in order to take into account forming-induced residual stresses. The elastic material parameters as well as the temperature dependent flow curves for 16MnCrS5 are shown in Fig. 28. According to Doege et al. [26] 16MnCrS5 shows no significant strain rate dependency for strain rates below 8 1/s. Since the maximum strain rate in the forming zone amounts to 4 1/s, the strain rate sensitivity of the flow stress was neglected in the simulations.

According to Tekkaya and Gerhardt [36] modelling the die as an elastic object is necessary in order to correctly predict the reduction of residual stresses during the ejection process. Both punch and ejector were assumed to be rigid objects. The workpiece was discretized with linear 4-node elements with an average element size of 0.35 mm, whereas the forming zone was discretized more finely by means of a static mesh window, resulting in an element edge length of 0.15 mm. The overall number of elements in the workpiece amounts to about 8.000 elements. Due to the large plastic strains occurring, remeshing was conducted, whenever the local element distortion led to a negative element Jacobian. The die was discretized with a structured mesh with an average mesh size of 1.2 mm. In contact regions the element edge length was decreased to 0.5 mm and 0.4 mm. The settings resulted in an overall element number of approximately 10.000 elements (Fig. 29).

The Coulomb friction model was used for the tool-workpiece interaction with a friction coefficient of μ = 0.04. The cylindrical workpiece geometry was defined with an initial diameter of d0 = 30 mm and an initial length of l0 = 71 mm. The die radii as well as the semi-cone angle of the dies were kept constant for all investigations (r = 3 mm and 2α = 90°).

B Influence of inhomogeneous pre-strain distributions on the flow stress evaluation

It was shown, that cylindrical specimens pre-strained by forward rod extrusion possess an inhomogeneous strain distribution over the specimen radius. Due to this, the question arises, if a flow stress evaluation by means of tensile tests on the pre-strained specimens can be conducted utilizing an area-weighted average strains \( \overline{\varepsilon} \) with sufficient accuracy regarding the actual pre-strain distribution. To validate the procedure, simulations of tensile tests with pre-strained cylindrical specimens have been conducted, utilizing the flow curve given by Fig. 27. At first, a simulation was conducted with the actual pre-strain distribution generated by forward rod extrusion. In addition, a simulation was conducted, utilizing a homogenous strain distribution equal to the area-weighted average strain \( \overline{\varepsilon} \) from Fig. 11. The highest extrusion strain of εex = 1.5 was considered, since it shows the largest deviation between the area-weighted average strain \( \overline{\varepsilon} \) and the actual strain distribution ε(r).

Figure 30 shows the true stress-strain curves calculated from the force F and displacement u for the two simulations. The error between the two generated flow curves is less than 0.44 MPa, which corresponds to a deviation of 0.045%.

Following from the numerical results, the inhomogeneous strain distribution of pre-strained specimens can be considered in the flow curve evaluation by assuming the pre-strain εpre to be equal to the area-weighted average strain \( \overline{\varepsilon} \).

In the numerical procedure an initial flow curve is needed to obtain accurate area-weighted average strains. This raises the question, how strongly the area-weighted average strains depend on the accuracy of the generally unknown flow curve. To analyse the sensitivity of the area-weighted average strain on the underlying flow curve, additional simulations have been conducted, utilizing a generic Swift-type hardening curve. Starting from an initial set of hardening parameters (C = 400 MPa, ε0 = 0.01, n = 0.2) the parameters were varied within a range of ±100%. The maximum resulting deviation of the area weighted-average strains in the region of specimen extraction (d = 8 mm or r2 = 16 mm) amounts to less than 5%, indicating that the plastic deformation along the central axis is not significantly affected by the hardening parameters.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hering, O., Kolpak, F. & Tekkaya, A.E. Flow curves up to high strains considering load reversal and damage. Int J Mater Form 12, 955–972 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12289-018-01466-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12289-018-01466-z