Abstract

Research on party differences in environmental policy, so far, has developed ambiguous results. While we, generally, assume parties to make a difference in policy-making, some scholars point to party indifferences in environmental issues. Thus, whether and how parties take different positions on the issue and whether their positions impact environmental policy output and outcome is still up for debate. To further our knowledge of party positions in this area, we propose to include parties’ perceptions of environmental problems when analysing their general stances. Based on pertinent policy analysis literature, we differentiate seven dimensions of environmental problems and develop an approach that we apply to party manifestos. By analysing the platforms of 20 parties from three European countries, we illustrate its potential contributions to established measurements based on CHES and CMP data. The analysis indicates that parties differ considerably concerning their problem perception ranging from simple to holistic views on environmental policy. Importantly, we can highlight some differences between parties otherwise omitted in existing measurements. Overall, our inquiry shows that some parties, e.g., Green parties, coherently show a holistic problem perception while others, e.g., Liberals, differ considerably, casting doubt on the assumption of clear-cut party family positions.

Zusammenfassung

Die bestehende Forschung zur Parteidifferenz liefert mit Blick auf das Feld der Umweltpolitik bisweilen widersprüchliche Ergebnisse. Während wir im Allgemeinen davon ausgehen können, dass Parteien einen Unterschied in der Politikgestaltung machen, deuten einige Studien auf eine Indifferenz in Umweltfragen hin. Ob und wie Parteien unterschiedliche Positionen in der Umweltpolitik einnehmen und ob ihre Positionen Auswirkungen auf Policy Output und Outcome haben, steht daher weiterhin zur Debatte. Um die Forschung zu Parteipositionen in diesem Bereich zu erweitern, schlagen wir vor, die Wahrnehmung von Umweltproblemen durch die Parteien in die Analyse ihrer Positionen in diesem Politikfeld einzubeziehen. In Anknüpfung an die bestehende Forschung zur Politikanalyse differenzieren wir sieben Dimensionen von Umweltproblemen und entwickeln einen Ansatz, den wir auf Parteiprogramme von 20 Parteien aus drei europäischen Ländern anwenden. Zudem illustrieren wir, wie dieser Ansatz die bestehende Messung von Parteipositionen basierend auf CHES- und CMP-Daten ergänzen kann. Unsere Analyse zeigt, dass sich die Parteien hinsichtlich ihrer Problemwahrnehmung von einfachen bis hin zu ganzheitlichen Ansichten zur Umweltpolitik erheblich unterscheiden. Mit unserem Ansatz gelingt es uns, Unterschiede zwischen den Parteien hervorzuheben, die in bestehenden Ansätzen verborgen bleiben. Insgesamt zeigt unsere Untersuchung, dass einige Parteien, z. B. die grünen Parteien, kohärent eine ganzheitliche Problemwahrnehmung aufweisen, während andere, z. B. liberale Parteien, erhebliche Unterschiede aufweisen. Diese Ergebnisse begründen zudem Zweifel an der Annahme kohärenter Positionen innerhalb von Parteifamilien.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Environmental policy has moved steadily to the fore of international and national policy agendas. Due to challenges linked to a sustainability transition and, in particular, climate change, it has become a significant point of societal and political contention. Recent research on political parties confirms stark differences regarding these issues and thereby doubts the traditional conception of environmental policy as a valence issue (Carter et al. 2018; Farstad 2018). However, the consistent estimation of party positions in the field of environmental policy is still at issue. In particular, this poses a constant challenge for research on partisan effects, which centrally hypothesises clear-cut patterns of parties’ effects depending on their policy positions. Partisan theory has proved to be a practical explanation in a variety of policy fields (e.g., Schmidt 1996; Zohlnhöfer 2019) and also in environmental policy, it has provided valuable insights pointing, most importantly, to an impact of Green parties (Knill et al. 2010; Jahn 2016; Green-Pedersen 2019). General ideological perspectives, e.g., based on the traditional left-right axis, have been found to be helpful in differentiating party positions (Farstad 2018). However, scholars also question whether environmental policy positions correlate with the traditional socio-economic cleavage or rather relate to social-cultural conflicts (Kitschelt 1989; Dalton 2009). For instance, Töller (2017) demonstrates party indifferences instead of clear-cut positions along the traditional left-right divide and, thus, proves empirical inconsistencies in the research on environmental policy positions. These seemingly blurry party positions might be due to how research estimates parties’ stances on the environment leading us to our main question: What should we understand as environmental policy to detect parties’ positions? Therefore, we propose to consider parties’ reflections on environmental problems and their complex nature as an approach to trace a more fundamental understanding of party positions. To this end, this article should be understood as a starting point and provide a way for scholars to incorporate parties’ different perspectives on environmental problems.

So far, existing approaches to grasp parties’ environmental positions generally reveal three central shortcomings. First, they either address contention on environmental policy unidimensional reducing it to the conflict between ecology and economy and thereby discounting the complexity of environmental issues (Bakker et al. 2020). Second, they simply ignore existing disagreements following the conception of environmental policy as a valence issue (Volkens et al. 2020). Third, considering the environment as a policy area “broad in the sense that it contains a wide number of policy questions relating to the many ways in which human behaviour influences and potentially degrades the environment” (Green-Pedersen 2019, p. 114; cf. Böcher and Töller 2012), research often tackles only one aspect of this broad field and thereby lacks comparability across studies. To address these shortcomings, we propose to go beyond existing approaches to party differences and focus on problem structure as a fine-grained concept of environmental policy, enabling a meta-view on parties’ environmental positions. For this purpose, we adopt seven distinct features of environmental problems derived from pertinent literature of environmental policy analysis (Böcher and Töller 2012; Carter 2018) and present the first approach to transfer these accounts from the policy- to the politics-dimension. At the core of our investigation, we do not explore whether parties differ in how salient they address environmental policy. While salience signals which issues parties deem most relevant, e.g. for an election, we seek to scrutinise general perceptions of environmental problems (Båtstrand 2014). We pursue a more fundamental perspective that reflects the complexity of environmental issues in various dimensions, and that goes beyond the conception of environmental policy as a dichotomy of economic development or environmental protection and, thus, moves past investigating whether parties assign priority to economic development vis-à-vis environmental protection (or vice versa).

Specifically, we argue that examining whether parties address environmental problems in a holistic, complex or simple fashion can add a fruitful analytical layer to existing approaches and may contribute to the ongoing clarification of party positions in environmental politics.

While this contribution is mainly a conceptual endeavour, for illustration, we apply the dimensions of environmental problems to party manifestos of 20 parties from three European countries. Austria, Germany and Sweden are the most suitable cases for this endeavour since they are widely recognised as environmental pioneers (e.g. Duit 2016) and feature the environment as a well-established issue of party politics. If our attempt cannot shed more light on party positions in these countries, it does probably not provide an added value. To be clear, following this procedure, in this article we cannot make general empirical claims on party positions on environmental issues. Instead, our objective is, first, to investigate the added conceptual value of considering environmental problem perceptions for future investigation of partisan stances and, second, to refine and elaborate on our approach deduced from the literature by speaking to practical cases (Adcock and Collier 2001).

The article proceeds as follows: First, we reflect the state of the art on party positions in the field of environmental policy and explain why we deem it useful to focus on problem perception in the first place. Second, we propose an approach that can help to highlight parties’ stances on environmental policy by considering different dimensions of environmental problems. We then illustrate the added value by applying our approach to party manifestos. The last section discusses our approach and critically reflects on its contribution.

2 Analysing party positions in environmental politics

As stated in the introduction, grasping party positions in environmental policy has proven to be much more complicated than in other domains, such as social policy (Töller 2017). Previous research often approaches partisan differences by focusing on single dimensions. For instance, assuming environmental policy to be about the degree of state regulation, scholars point to the relevance of party positions on a left-right axis (e.g. Farstad 2018). However, this approach risks neglecting the complex nature of environmental policy, which cannot always be reduced to a unidimensional conflict between free markets and state intervention. For instance, Knill et al. (2010) point to Christian parties assigning importance to environmental protection based on their religious worldview, e.g. aiming to protect God’s Creation (see also Töller 2017). Moreover, considering policy-making on genetically modified crops, Christian-conservative parties take a much more cautious position than their general market-friendly position would imply (Bäck et al. 2015).

Principally, a unidimensional conceptualisation of environmental conflicts (i.e., on a left-right-divide) is almost contrary to the complexity of environmental and climate protection. Scholars point to global dimensions of environmental policy (e.g. Lenschow et al. 2016), the central role of individual behaviour (e.g. Spaargaren 2003), general questions regarding the relationship between development and economic growth (Kallis et al. 2018), and the overall interconnectedness of areas relevant for sustainability (Hickmann et al. 2020). Somewhat surprisingly, researchers rarely seek to investigate parties’ environmental positions in a more complex way. For instance, Abou-Chadi (2016) combines measurements on parties’ environmental positions and their stances on productivity (based on the CMP’s codes per501 and per410)Footnote 1. However, while this is a valuable approach, it still focuses on environmental aspects vis-à-vis economic ones. Considering these aspects and the ambiguous state of the art on party differences in environmental policy, we propose a new perspective by taking cues from environmental policy analysis.

Policy research determines problem perceptions as essential elements of the policy process (e.g. Lowi 1972; Heinelt 2003; Böcher and Töller 2012). In this vein, literature has discussed various forms of problems (i.e. simple, complex, (super-)wicked problems), which show varying agreement or disagreement on problem definition and problem-solving among political actors (Roberts 2000; Levin et al. 2012). However, it is important to note that problem structures do not determine politics but are filtered by political actors. This holds true for recognising a problem or problem-definition (“What is actually a problem?”), which is well-examined in the agenda-setting literature (Dery 2000), and for the more fine-grained question of, “What exactly does this problem involve?”. The latter is not covered by salience measures that address an actor’s dedication to a policy problem concerning others. Still, it is rather a positional issue pointing to the fact that different actors take different views on which problem dimensions are part of an issueFootnote 2. For instance, parties might perceive the complexity of environmental problems and deeply engage in them across policy fields. For the actual policy output, such a holistic problem perception is likely to be reflected in holistic policy measures, although other factors (e.g., coalition partners or socio-economic conditions) need to be considered as well.

Specifically, we draw upon seven dimensions of environmental problem structure. Six of these dimensions were proposed by Böcher and Töller (2012), which by and large match with the explanations made by Carter (2018)Footnote 3. In light of the broader literature and our initial data analysis, we added a seventh dimension, i.e., environmental justice. In a nutshell, environmental problems are described in seven distinct dimensions: as a common good, regarding the persistency of problems, their spatial and temporal dimension, with respect to the uncertainty of solutions, regarding the cross-sector integration of environmental objectives and the reference to aspects of environmental justice. While these descriptions were largely developed to guide policy analysis, we deem them helpful in guiding our inquiry.

3 Our conceptual contribution: transferring problem dimensions from policy research to politics?

To apply the seven dimensions of environmental problems described in pertinent basic literature empirically in the politics dimension, we take cues on concept-building from Goertz (2006) and, in particular, on interpretative approaches from Adcock and Collier (2001) and Özvatan and Siewert (2020). Consequently, we elaborate on the seven dimensions by discerning three levels of a concept: basic level, secondary level and indicator level. While the basic level corresponds directly with the dimensions, the secondary level concepts represent the most important components of these dimensions emphasised in the literature. On the indicator level, we operationalised secondary level concepts for the application to political parties’ positions, i.e., party manifestos, and developed codes guiding our qualitative content analysis. Thus, the codes for analysing data are deducted from the secondary concepts and capture its definitional content (Özvatan and Siewert 2020, p. 34). Goertz (2006) suggests that it is fruitful for concept-building to clarify the relationship between the three tiers of a concept. We concurred with this claim and decided for a hybrid of the classic essentialist form and the family resemblance form of concept-building, taking a component of environmental problem structure as given in a party’s problem perception if more than half of the secondary-level components are addressed in a party manifesto. This means that none of the secondary-level components as such is a sufficient condition for the systematic concept, but only if at least 50% of the components are present, they form a sufficient configuration for it (Özvatan and Siewert 2020). Concerning the relation between secondary and indicator level, we apply a minimum-threshold approach and deem it sufficient for a secondary level concept if it is represented by one code in the data. We will illustrate our understanding of concept-building in the next section. Furthermore, this causal perspective lets us clarify another peculiarity of our operationalisation regarding party manifestos. As party programmes are more focused on solutions than on problems, we often have to look for the effects of the secondary level concepts to track them down (Goertz 2006). However, regularly, parties also include problem descriptions in their programmes.

3.1 Dimensions of environmental problem structure Footnote 4

The first dimension of environmental problems is called “environment as a common good” and addresses a fundamental characteristic intrinsic to almost all environmental policy issues. This applies to the global commons like oceans and equally to local commons such as lakes. In their nature, these commons are both non-excludable and non-rival (Böcher and Töller 2012; Carter 2018). However, we deem it unlikely that parties deal with such ontological issues in their platforms, considering party programmes’ rather pragmatic nature. What parties might address instead and what is equally discussed in the context of environmental problem structure is the overuse of these commons resp. planetary boundaries, which, ultimately, entails a neutralisation of the two mentioned characteristics and brings to the fore two follow-up elements of the related problem structure: the free-rider problem and the asymmetry of interest powers (ibid.). First, the free-rider problem refers to the well-known tragedy of the commons that no one will be willing to take responsibility for problem-solving if other actors might benefit from the taken measures and could take action just as well (Hardin 1968). We refer to this component as common responsibility. Second, the asymmetry of actors’ power relates to this inherent problematic constellation and points to the fact that resources between potential polluters, being mostly a highly cohesive (economic) actors, and potentially affected persons, plants and animals, represented by a diffuse mass of actors, reveal huge imbalances between the parties (Böcher and Töller 2012; Carter 2018).

Second, we consider “spatial distributions” of environmental policy. This trait of environmental issues becomes evident in, e.g., the pollution of cross-border rivers and has become an almost obvious element of environmental problem structure due to the increasing awareness of most environmental problems’ globality (ibid.). However, recognising a transboundary quality of environmental issues is only one part of this dimension, and it holds true equally for the distribution across and within nation-states. It is closely intertwined with the need to differentiate political measures and expectations based on geographical and economic prerequisites. As we are interested in a fundamental conception of national parties’ environmental policy positions, the essential second aspect is if parties recognise the need to take a differentiated view on environmental policy issues pertaining to regional idiosyncrasies (e.g. Töller 2017). For internal validity reasons, such references must be made directly relating to environmental issues, so that general references of multi-level governance are insufficient.

Third, we turn to “persistency”. The persistency of environmental problems is a complex concept comprising several components. Böcher and Töller conclude that persistent problems imply “a high and diffuse number of polluters and that no simple technological solutions are available” (2012, p. 95, own translation). In particular, they elaborate on the former point, referring to difficulties that result from contradicting interests and rationalities of the involved actors and sectors. While we agree on the necessity to include solutions that go beyond only technological innovations, i.e. social innovations, in search for the concept of persistency, we are less sure when it comes to the vast number of polluters. Sure enough, this is a fundamental element of environmental problem structure. However, in the context of our superordinate endeavour of concept-building, we see a need to distinguish it from the component of “integration”. To capture the essential elements of persistency, we, therefore, turn to Jänicke and Volkery (2001), who were among the first that adopted the concept of persistent environmental problems scientifically. Like Böcher and Töller (2012), they suggest the need to go beyond technical solutions and emphasise the responsibility of all parts of society to tackle persistent problems. For them, the latter goes beyond merely integrating climate or sustainability concerns into other areas but refers to the need to develop a joint societal approach to tackle environmental problems. Furthermore, they appeal to the literal origin of the term “persistency” and highlight two elements yielded from the longevity of the problem: a previous failure of political problem-solving as well as the urgency of the problem regarding a high damage potential which continues to increase and whose solution, therefore, is pressed for time.

Fourth, the literature points to a “temporal dimension”. Temporality has been debated as an essential characteristic of environmental issues since the inception of modern environmentalism in the 1960s (Milfont and Demarque 2015). It is essentially about the long-term nature of both environmental problems’ ramifications and environmental policies’ effects, which tend to materialise with a substantial delay. This long-term orientation is often in conflict with the short-term interests of (political) actors (e.g., re-election) and thereby constitute a “temporal dilemma” for political action (Milfont and Demarque 2015, 373; Böcher and Töller 2012). Furthermore, this dimension relates to intergenerational justice, which is closely connected to the idea of sustainable development (Brundtland et al. 1987). We expect this dimension to be reflected in party programmes by referring rather abstractly to inter-generational responsibility and setting concrete long-term goals for policy measures.

Fifth, environmental problems are characterised by “uncertainty”. The uncertainness relates to various aspects, ranging from the uncertainty of technical developments to the actual effect of policy measures to uncertain scientific insights, and generally, unsureness of what the future holds (Böcher and Töller 2012; Nair and Howlett 2017). We derive two sub-dimensions from existing research. The first captures the openness of processes and, thus, relates to the idea that a constant revision might be necessary to adapt to developments, e.g. new technical solutions. Hence, we investigate whether parties address uncertainty by pointing to a need for evaluation or revisiting approaches. Secondly, policy ambiguity refers to the uncertainness of scientific knowledge or the unclear impact of proposed solutions. Here, we inquire whether parties refer to potential inconclusive policy measures.

Sixth, the “integration of environmental problems” is crucial. While persistency refers to, e.g., a high number of relevant actors or sectors, integration captures the mainstreaming of environmental considerations in other policy areas as environmental problems are characterised by a cross-sectional nature (Jordan and Lenschow 2010; Böcher and Töller 2012). For instance, transport policy is tightly connected to climate policy since decisions made in this area might impact CO2 emissions. We conceptualise the dimensions of integration based on research on policy areas or subsystems (Baumgartner and Jones 1991). Therefore, we identify environmental policy integration where this policy area is linked to other areas in parties’ manifestos.

Finally, based on our inquiry, we propose to add another, seventh, dimension of environmental problem structure, namely an “environmental justice dimension”. Although Böcher and Töller or Carter have not included this dimension, it is often discussed as another inherent element of environmental problem structure elsewhere. The literature on environmental justice stresses that the causes and effects of environmental problems do not only differ in terms of space but crucially also in terms of their relation to societal groups, usually to the detriment of ethnic minorities and the poor (Holifield et al. 2017; Elvers 2011; Koch and Fritz 2014). In its essence, this interrelation goes beyond the simple integration of environmental issues into welfare policy. However, it depicts an additional inherent part of an environmental problem structure that can be applied equally to both inner-country and global contexts and that we could also find in our analysis of party manifestos.

To guide our analysis, we develop two guiding research questions. First, considering existing research on green parties and their position as issue-owners regarding environmental and climate policy, environmental issues are the essence of their worldview (Van Haute 2016). Thus, we ask whether they also address the most dimensions of environmental problems. Second, we draw upon literature on party families (e.g. von Beyme 1985) that suggests parties of the same party family to take unified positions in various policy contexts, which Mair and Mudde (1998) describe as “conventional wisdom” in political science. However, previous research shows green parties to take similar positions while mainstream parties have incorporated environmental issues to different degrees (Carter 2013; Rohrschneider and Miles 2015). Thus, we ask whether parties of the same family take similar and coherent positions regarding environmental problem dimensions and form, e.g., a green, social democratic, liberal or conservative perception of environmental problems.

4 Research design and methods

To further explore our theoretical considerations, we apply the identified dimensions to party manifestos of 20 parties in three European countries from the most recent national elections, respectively (Austria: 2019; Germany: 2017; Sweden: 2018). For this purpose, we first created a coding scheme as a central tool for the content analysis of manifestos. Second, we developed a basic index to synthesise the results derived from the coding process and prepared it for comparison with other measures of environmental policy positions.

Research into party positions and party identity often relies on manifestos being one of the few sources that allow cross-country comparison as most parties in advanced democracies prepare manifestos regularly. Thus, using manifestos allows us to identify positions at a certain point in time, usually before elections. For instance, Dolezal et al. (2012) show that manifestos represent a primary outlet for parties to “communicate their interpretations of the current state of the world and their policy prescriptions to improve on it” (p. 869). Båtstrand (2014) argues that manifestos are an outlet for parties to “speak freely” and in which they are “able to present the world exactly as they would like the electorate to see it” (p. 934). Thus, manifestos seem to be a suitable data source for detecting fundamental problem perceptionsFootnote 5. However, there are shortcomings of this approach (Volkens 2007). Manifestos are political documents used to highlight party positions to attract voters. Yet, this also holds true for political speeches by lead candidates or party chairs. Also, whether parties decide to discuss environmental problems in detail, nevertheless, signals their perception of the issue. Overall, we follow Volkens (2007) and her proposal to understand different approaches to measure party positions as complementary. Therefore, this contribution with its qualitative analysis of manifestos provides one puzzle piece in investigating parties’ environmental positions.

For the content analysis, we followed coding standards well-established in the literature (e.g. Behnke et al. 2010; Mayring and Fenzl 2014). In a first step, we developed a coding scheme that comprises representative phrases indicating the respective dimensions and ideas behind them (see codes in Table 1). Each code captures the definitional attributes of each subdimensions, whereby the codes are mutually exclusiveFootnote 6. First, to identify relevant paragraphs in the manifesto texts, we searched the documents for various terms (environment*, climate, sustainab*, ecolog*, bio*, resource*) in the respective language. Second, we analysed whether our codes were covered in these sections and suggested a problem subdimension. Note that we did not only include quasi-sentences containing these terms but context-sensitively searched the adjacent passages for relevant information and, thus, ultimately focused coherent paragraphs that represent our unit of analysis. As usual for content analysis, we proceeded iteratively, and in a pre-test, cross-checked our coding scheme and inter-coder reliability based on three selected party programmes. Thus, we reviewed and refined our categories and operationalisations and added the seventh category, “environmental justice” (Table 1).

To synthesise our results from a conceptually informed perspective and to illustrate related patterns within the group of parties, we develop a formative index of environmental problem perception (IEP), representing an unweighted additive index (Döring and Bortz 2016). The IEP relates our findings to the seven basic concepts constituting environmental problem structure and reflects which dimensions are primarily and comprehensively addressed by parties. We investigate whether a party takes on a dimension comprehensively based on the concept-building approach described above. Parties might address a variety of subdimensions without extensively dealing with a dimension. We understand a dimension as essentially addressed only if parties engage in at least 50% of the secondary level concepts. For instance, a party that only addresses one of three subdimensions related to a problem dimension does not fully address this dimension.

As we aim to propose an innovative way to investigate parties’ positions in environmental policy, we must ensure the validity of our measurement. In this regard, we follow Adcock and Collier (2001) and their guidelines for ensuring validity. We focus on content validation and convergent validation. In the first analytical step, we undertook three rounds of coding in which we refined the indicators and checked their relation to the basic concepts. By performing this fine-tuning of indicators, we sought to ensure content validity, i.e., that indicators are unequivocal and distinctively represent the secondary level concepts. We compared equally coded segments between different party programmes and coders. Furthermore, remaining ambiguous segments have been discussed within the research team and coded accordingly.

Secondly, we want to address convergent validation, which captures our measurement’s relation to other approaches. To our knowledge, there are no investigations that focus on parties’ problem perceptions and existing measurements of parties’ environmental positions are characterised by some shortcomings we discussed above. However, the two existing approaches, i.e., CMP and CHES, are able to distinguish parties’ positions in environmental politics even if they mainly focus on the relationship between environmental protection and economic growth. Thus, there should be some convergence between these existing approaches and our measurement. For instance, Green parties should, all in all, show the most complex perception of environmental problems, i.e., address most dimensions. To ensure validity and illustrate our approach as a useful second perspective on environmental party positions, we compare our results to party positions based on the CMP and CHES data (Bakker et al. 2020; Volkens et al. 2020).

5 Parties’ perception of environmental problems

To present parties’ perceptions of environmental problems, we will, first, provide an overview of the index of environmental problem perceptions (IEP) before we illustrate the added value of the IEP in combination with existing measurements of party positions. The latter shall also display the convergent validity of our proposal.

The IEP depicts to which extent the investigated parties apply comprehensive perceptions of environmental problems. To cover the main dimension resp. a basic level concept, parties need to contend with at least half of the subdimensions if applicable. Table 2 provides an overview of the results. We ascribe parties a holistic understanding of environmental problems when they refer to six or seven dimensions (> 2/3 of 8 possible values ranging from 0–7), a complex perception when they address three, four, or five, and a simple understanding when they refer to zero, one, or two dimensions (< 1/3 of 8 possible values).

In our analysis, 15 of the observed 19 parties are characterised by a complex or holistic perception of environmental problems, which echoes a trend towards mainstreaming environmental issues detected by Carter (2013). This is corroborated by the overall mean of four dimensions, indicating a (on average) complex understanding of environmental policy problems. However, regarding our data basis, it is equally clear that this trend covers not all parties since they scatter on the full range from zero to seven.

Turning to party families, only two are characterised by a coherent perception: all three Green parties display a holistic view, and the two Left parties represent a complex perception. The three Social democratic parties display either a complex or holistic perception. The three Christian Democratic parties take very diverse positions, with the Swedish KD not addressing environmental policy at all in its manifesto and the German CDU/CSU and the Austrian ÖVP displaying a complex view on environmental problems. Perhaps the most interesting case is the group of liberal parties: While the German FDP only addresses two dimensions, the two Swedish liberal parties refer to three (L_SE) and five (C_SE) dimensions and the Austrian NEOS is characterised by a holistic perception. Overall, this analysis of parties’ perception of environmental problems provides us with a perspective on how parties understand environmental politics. While some, e.g., those with a simple understanding, only refer to the need to integrate environmental concerns in other policy areas (such as infrastructure or economic policy), others, like the Green parties, discuss environmental policy as a highly complex and permanent topic which relates to (almost) all other areas of society and politics.

Regarding the emphasis of single dimensions, the distribution in our case sample did not reveal any discernible patterns, e.g., in the sense that all Social Democratic parties engage vigorously in the environmental justice dimension, which is closely linked to their ideological core. However, it is evident that all parties apply an integrational understanding of environmental policy—at least based on our relatively low threshold—and propose to mainstream environmental concerns in various policy areas. Furthermore, the dimension of uncertainty was only addressed once by the German Social Democrats. The SPD emphasises its openness towards new or unforeseen developments, e.g., technological innovation, that might help protect the environment. However, this was the only reference to the dimension of uncertainty in all manifestos investigated. This might have to do with the general nature of programmes in which parties propose ideas or develop concrete proposals. In this regard, a reference to future developments’ uncertainty might not function as an argument for any given policy proposal or might not help frame a party’s proposition.

To further illustrate the added value of an analysis of problem perceptions, we, first, contrast our results with parties’ stance on environmental policy based on CMP data, i.e. the per501 code (Volkens et al. 2020) and, second, with parties’ general position towards environmental sustainability based on CHES data (Bakker et al. 2020). Thus, we arrive at a more fine-grained picture of party stances on environmental issues.

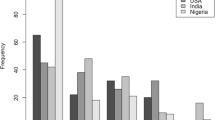

As our analysis relies on party manifestos, a comparison to parties’ positions based on the CMP data is obvious. We use a two-dimensional figure, in which the IEP functions as one and the CMP data as the other measurement, to show a much more fine-grained positioning of parties. For instance, ten parties score a value below 0.5 on the CMPs scale, measuring parties’ stances on environmental policy. However, we can detect differences between parties’ positions when analysing their positions with our measurement. Considering only the CMP’s per501 coding, the German CDU/CSU and SPD, Austrian NEOS and ÖVP take similar positions. But when we consider their conception of environmental problems, the much more multidimensional understanding of the SPD and NEOS becomes evident. The example of the Sweden Democrats and Austrian SPÖ further illustrates the added value of combining two measurements of environmental positions. Considering only the CMP data, both parties take similar positions. However, by combining CMP and IEP data, we can show that the SPÖ displays a much more complex perception of environmental problems. (Fig. 1).

Second, we also want to contrast our results with party positions on environmental sustainability based on the CHES database (Fig. 2). While party positions are assessed by experts and, thus, differ from our data, it helps illustrate the added value of our approach. In the same fashion as above, we use a two-dimensional figure, in which the IEP functions as one and the CHES data as the other measurement. As with the comparison to the CMP data, a more fine-grained picture emerges. For instance, while our sample’s three social democratic parties score similarly in the CHES database and slightly prioritise economic growth vis-à-vis environmental protection, they show different perceptions of environmental problems based on our measurement. At the same time, however, we see that a complex and not even a holistic problem perception is a necessary condition for a distinctive pro-environmental position of a party.

Overall, by combining two measurements of environmental positions, we can show differences in how specific measures suggest different degrees of environmental engagement of individual parties and clear discrepancies among parties of a single party family. Our sample’s six parties with the most multidimensional perception of environmental problems are three Green, two Social Democratic and one Liberal party. While the Green parties take the most coherent position and can be characterised as a party family with a similar (holistic) perception of environmental problems, our analysis sheds some doubt on the general assumption of coherent party family positions. This is not to be understood as a criticism of the CHES or CMP data but as an addition to arrive at a more detailed picture.

Finally, we want to come back to the issue of validity. As described above, we not only performed several rounds of refinement to ensure content validity, we also want to highlight our measurement’s convergence to existing approaches. As Fig. 1 illustrated, the relation of our measurement to party positions based on the CMP data (i.e. per501) clearly shows some convergence. For instance, the green parties in our sample are the ones emphasising environmental protection emphatically (based on the CMP measurement) and refer to the most dimensions of environmental problems. Similarly, centre-right parties, e.g., conservative or liberal parties, refer to fewer dimensions of environmental problems and also tend to prioritise economic growth over environmental protection. While this comparison shows some convergence between existing approaches and our investigation, it also shows some differences. For instance, the Austrian liberal party NEOS refers to six dimensions of environmental problems and, thus, is similar to, e.g., the German Social Democrats, although it tends to emphasise environmental protection as measured by, e.g. the per501 indicator in the CMP data. The same holds true for the comparison with the CHES data. However, as this approach is based on expert surveys, we primarily deem the CMP data a crucial reference point for illustrating convergent validity.

6 Discussion & conclusion

This analysis was motivated by our aim to arrive at a more fine-grained and comprehensive picture of parties’ environmental positions. It is grounded in the premises posited by policy analysis literature that environmental policy is inherently complex in its problem structure and that this problem structure determines actors’ positions central to the policy processes. Understanding parties to be central in this regard, we used descriptions of environmental policy’s multi-faceted nature to analyse party manifestos and develop the Index of Environmental Problem Perception. This approach’s key idea is to go beyond contrasting environmental and economic policy (or any other policy area for that matter) and, instead, investigate the fundamental view of parties on the specific field of the environment. In light of research on partisan effects, we understand a more holistic view on environmental issues to reflect not only that a party is intensely engaged in the issue but also that it is likely to pursue more systematic policy measures. In contrast, a rather simplistic understanding suggests a perception of the environment as a subordinate add-on policy. While we understand this contribution mostly as a conceptual one that proposes a way to utilise environmental problem dimensions described in the literature for party research, we also sought to present some illustration of the approach’s added value. Thus, we developed two guiding research questions. First, we asked whether Green parties address the most dimensions of environmental problems. Our analysis shows that they do—all three Green parties display a holistic perception of environmental problems. However, also two Social Democratic and one Liberal party do so. Due to our conceptual focus, we cannot intensively discuss the reasons for why, e.g., Social Democratic parties show a similar problem perception as Green parties, yet rooted in a socialist ideology, it is no surprise that aspects such as (environmental) justice fit their general stances. This leads directly to our second question: Do parties of one family show similar perceptions of environmental problems. Based on the presented first attempt to investigate this in manifestos, we come to a differentiated conclusion. Our results cast some doubt on comparative party research’s “conventional wisdom”, whereby parties are part of families with similar positions, regarding environmental policy (Mair and Mudde 1998). Some party families show similar profiles, e.g., Green or Left or Conservative parties, whereas the three Liberal and Social Democratic parties included in our inquiry do not form homogenous families but display different perceptions of environmental problems. This might reflect more general macro-processes of conflicting but subsequently converging cleavage structures (e.g. Decker 2019) that leave their mark on party families and let them struggle to adopt environmental issues to their ideology.

Assessing our general contribution critically, we argue that considering parties’ perceptions of environmental problems can add a useful perspective to analysing party positions in environmental policy. As shown above, this perspective helps distinguishing party positions otherwise omitted. For instance, we could show the (stark) differences between Liberal or Social Democratic parties that score similarly in the CHES or CMP data by applying our approach. In this regard, we aim to contribute to a growing body of research addressing parties’ environmental positions (e.g. Båtstrand 2014; Carter et al. 2018). Similar to these attempts, we approached the data by hand-coding. Research on parties’ environmental positions predominantly relies on qualitative attempts to advance the otherwise unidimensional conceptualisation of environmental politics (e.g. per501 in the CMP data). In our view, research on this issue is still in an identification stage, where several approaches suggest ways to advance our understanding of parties’ environmental preferences. In the medium term, these approaches should be combined and applied to a larger number of manifestos to provide a database for further analysis.

However, as this is a first attempt to utilise the problem dimensions discussed in policy research for investigating party differences, we see some limitations, at this stage, that indicate needs for future research. First, research should dig deeper into the theoretical foundations regarding the conceptual level. Although the dimensions used here to distinguish problem perception are grounded in extensive research, a critical discussion concerning its application and operationalisation is needed. In Goertz’s (2006) terms, it is interesting if and how the numerous concepts of environmental policy interrelate on the three conceptual levels and concerning the superior concept. For instance, it is unclear how secondary-level concepts, if at all, should be weighed in relation to the systematic concepts. Considering, e.g., the three components of the dimension “common good” could at first suggest a hierarchical relationship as parties that emphasise a common responsibility, logically, should also be aware of planetary boundaries. However, as the relation to the asymmetry of actors’ power is less clear and in general, the relationships (in all dimensions) are not explicated sufficiently in the literature, we opted for the more pragmatic form of concept-building and perceive two of three dimensions as sufficient independent of which conditions are present. This suffices for our main goal of making a case for our approach in general and ensures better comparability between the conceptualisation of the seven dimensions, but more generally indicates a need for future research to reflect these interrelations in more detail.

A second aspect relates to our empirical illustration and its generalisability. To our understanding, the main contribution of our approach has been to transfer well-established insights from environmental policy analysis that, so far, have been neglected by the research on party positions. We could illustrate its applicability for parties in three European countries. Key insights from this application are that not only Green parties but also several other parties display a holistic view on environmental problems establishing a trend by which also mainstream parties increasingly address environmental policy (Carter 2013). Interestingly, this process is evident not only among parties of the left but also some liberal and conservative parties (e.g. the ÖVP) that emphasise the complexity of environmental problems (see Jahn 2016). However, whether this is a continuous process or whether political competition (e.g. a turn to possible coalition partners) is relevant in this regard cannot be investigated here (see, e.g. Green-Pedersen 2019).

In terms of overall generalisability, regarding changing cleavage structures and increasing dynamics pertaining to the recently increasing salience of the environmental issue, our results have to be put into perspective as our case sample is limited in terms of time and space. Whether environmental problem perceptions of individual parties and whole party families or even systems have changed (consistently) over time is an interesting issue for future research that should be investigated in various countries, including other than environmental pioneer states.

Third, another key question concerns the implications of the identified varying problem perceptions for policy analysis and, in particular partisan theory. On the one hand, we have to conclude that assuming parties’ environmental policy positions based on party families remains a fuzzy business that needs to be carried out case-sensitively despite certain patterns along a left-right spectrum. On the other hand, we presumed parties to have a more systematic take on environmental policy measures, the more holistic their problem perception is. Thus, investigating possible correlations between parties’ IEP score and approaches addressing policy mixes for environmental issues should be worthwhile (Kern et al. 2019; Rogge and Reichardt 2016; Schaffrin et al. 2015; Howlett and Cashore 2009). Finally, the study of environmental problem perceptions seems to reveal partisan predispositions of early-phase environmental policy-making in terms of problem-definition and agenda-setting. Thus, it adds to the foundations of investigating partisan effects in environmental policy.

Notes

For the discussion of differences between estimating political parties’ substantive policy positions or its emphasis of an issue in terms of saliency see, e.g. Laver (2001).

By centrally following Böcher and Töller (2012), we also adopt their broad understanding of environ- mental policy, including, e.g. climate change issues.

For an overview see Table 1 below.

Another way to assess party positions is the use of expert survey. However, existing survey lack a more complex questionnaire on environmental policy. Additionally, they are characterized by several shortcomings discussed by Budge (2000). In this light, we decided to use manifestos.

In one paragraph, more than one code can occur.

References

Abou-Chadi, T. 2016. Niche Party Success and Mainstream Party Policy Shifts – How Green and Radical Right Parties Differ in Their Impact. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 46:417–436.

Adcock, Robert, and David Collier. 2001. Measurement validity: a shared standard for qualitative and quantitative research. American Political Science Review 95(3):529–546.

Bäck, Hanna, Marc Debus, and Jale Tosun. 2015. Partisanship, ministers, and biotechnology policy. Review of Policy Research 32(5):556–575.

Bakker, Ryan, Liesbet Hooghe, Seth Jolly, Gary Marks, Jonathan Polk, Jan Rovny, Marco Steenbergen, and Milada Vachudova. 2020. 1999–2019 Chapel Hill expert survey trend file. Version 1.0.

Baumgartner, Frank R., and Bryan D. Jones. 1991. Agenda dynamics and policy subsystems. The Journal of Politics 53(4):1044–1074.

Behnke, Joachim, Nina Baur, and Nathalie Behnke. 2010. Empirische Methoden der Politikwissenschaft. Paderborn: Schöningh.

von Beyme, Klaus. 1985. Political parties in Western democracies. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Böcher, Michael, and Annette Elisabeth Töller. 2012. Umweltpolitik in Deutschland: eine politikfeldanalytische Einführung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Brundtland, Gro Harlem, M. Khalid, S. Agnelli, S. Al-Athel, and B.J.N.Y. Chidzero. 1987. Our common future. New York: United Nations.

Budge, Ian. 2000. Expert judgements of party policy positions. Uses and limitations in political research. European Journal of Political Research 37:103–113.

Båtstrand, Sondre. 2014. Giving content to new politics: from broad hypothesis to empirical analysis using Norwegian manifesto data on climate change. Party Politics 20(6):930–939.

Carter, Neil. 2013. Greening the mainstream: party politics and the environment. Environmental Politics 22(1):73–94.

Carter, Neil. 2018. The politics of the environment: ideas, activism, policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carter, Neil, Robert Ladrech, Conor Little, and Vasiliki Tsagkroni. 2018. Political parties and climate policy: a new approach to measuring parties’ climate policy preferences. Party Politics 24(6):731–742.

Dalton, Russell J. 2009. Economics, environmentalism and party alignments: a note on partisan change in advanced industrial democracies. European Journal of Political Research 48(2):161–175.

Decker, Frank. 2019. Kosmopolitismus versus Kommunitarismus: eine neue Konfliktlinie in den Parteiensystemen? ZfP Zeitschrift für Politik 66(4):445–454.

Dery, David. 2000. Agenda setting and problem definition. Policy Studies 21(1):37–47.

Dolezal, Martin, Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Anna Katharina Winkler. 2012. The life cycle of party manifestos: the Austrian case. West European Politics 35(4):869–895.

Döring, Nicola, and Jürgen Bortz. 2016. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften, 5th edn., Wiesbaden: Springer.

Duit, Andreas. 2016. The four faces of the environmental state: environmental governance regimes in 28 countries. Environmental Politics 25(1):69–91.

Elvers, Horst-Dietrich. 2011. Umweltgerechtigkeit. In Handbuch Umweltsoziologie, ed. Matthias Groß, 464–484. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Farstad, Fay M. 2018. What explains variation in parties’ climate change salience? Party Politics 24(6):698–707.

Goertz, Gary. 2006. Social science concepts: a user’s guide. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Green-Pedersen, Christoffer. 2019. The reshaping of West European party politics: agenda-setting and party competition in comparative perspective. : Oxford University Press.

Hardin, Garrett. 1968. The tragedy of the commons. Science 162(3859):1243–1248.

Heinelt, Hubert. 2003. Politikfelder: Machen Besonderheiten von Policies einen Unterschied. In Lehrbuch der Politikfeldanalyse, ed. Klaus Schubert, Nils C. Bandelow, 239–256. München, Wien: Oldenbourg.

Hickmann, T., L. Partzsch, P. Pattberg, et al. 2020. Mehr Engagement der Politikwissenschaft in der Anthropozän-Debatte. Politische Vierteljahresschr 61:659–670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11615-020-00275-x

Holifield, Ryan, Jayajit Chakraborty, and Gordon Walker. 2017. The Routledge handbook of environmental justice. : Routledge.

Howlett, Michael, and Benjamin Cashore. 2009. The dependent variable problem in the study of policy change: Understanding policy change as a methodological problem. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis 11(1):33–46.

Jahn, Detlef. 2011. Conceptualizing left and right in comparative politics: towards a deductive approach. Party Politics 17(6):745–765.

Jahn, Detlef. 2016. The politics of environmental performance. Institutions and preferences in industrialized democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jänicke, Martin, and Axel Volkery. 2001. Persistente Probleme des Umweltschutzes. Natur und Kultur 2(2):45–59.

Jordan, Andrew, and Andrea Lenschow. 2010. Environmental policy integration. A state of the art review. Environmental Policy and Governance 20(3):147–158.

Kallis, Giorgos, Vasilis Kostakis, Steffen Lange, Barbara Muraca, Susan Paulson, and Matthias Schmelzer. 2018. Research on degrowth. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 43:291–316.

Kern, Florian, Karoline S. Rogge, and Michael Howlett. 2019. Policy mixes for sustainability transitions: new approaches and insights through bridging innovation and policy studies. Research Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103832

Kitschelt, Herbert. 1989. The logics of party formation: structure and strategy of Belgian and West German ecology parties. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Knill, Christoph, Marc Debus, and Stephan Heichel. 2010. Do parties matter in internationalised policy areas? The impact of political parties on environmental policy outputs in 18 OECD countries, 1970–2000. European Journal of Political Research 49(3):301–336.

Koch, Max, and Martin Fritz. 2014. Building the eco-social state: do welfare regimes matter? Journal of Social Policy 43(4):679–703.

Laver, Michael. 2001. Position and salience in the policies of political actors. In Estimating the policy positions of political actors, ed. Michael Laver, 66–76. London, New York: Routledge.

Lenschow, Andrea, Jens Newig, and Edward Challies. 2016. Globalization’s limits to the environmental state? Integrating telecoupling into global environmental governance. Environmental Politics 25(1):136–159.

Levin, Kelly, Benjamin Cashore, Steven Bernstein, and Graeme Auld. 2012. Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy Sciences 45(2):123–152.

Lowi, Theodore J. 1972. Four systems of policy, politics, and choice. Public Administration Review 32(4):298–310.

Mair, Peter, and Cas Mudde. 1998. The party family and its study. Annual Review of Political Science 1(1):211–229.

Mayring, Philipp, and Thomas Fenzl. 2014. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung, ed. N. Baur and J. Blasius. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. 543–556.

Milfont, Taciano L., and Christophe Demarque. 2015. Understanding environmental issues with temporal lenses: issues of temporality and individual differences. In Time perspective theory; review, research and application, 371–383. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Nair, Sreeja, and Michael Howlett. 2017. Policy myopia as a source of policy failure: adaptation and policy learning under deep uncertainty. Policy & Politics 45(1):103–118.

Özvatan, Özgür, and Markus B. Siewert. 2020. Konzepte und Konzeptformierung. In Handbuch Methoden der Politikwissenschaft, ed. Claudius Wagemann, Achim Goerres, and Markus Siewert, 31–61. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Roberts, Nancy. 2000. Wicked problems and network approaches to resolution. International Public Management Review 1(1):1–19.

Rogge, Karoline S., and Kristin Reichardt. 2016. Policy mixes for sustainability transitions: an extended concept and framework for analysis. Research Policy 45(8):1620–1635.

Rohrschneider, Robert, and Matthew R. Miles. 2015. Representation through parties? Environmental attitudes and party stances in Europe in 2013. Environmental Politics 24(4):617–640.

Schaffrin, André, Sebastian Sewerin, and Sibylle Seubert. 2015. Toward a comparative measure of climate policy output. Policy Studies Journal 43(2):257–282.

Schmidt, Manfred G. 1996. When parties matter: a review of the possibilities and limits of partisan influence on public policy. European Journal of Political Research 30(2):155–183.

Spaargaren, Gert. 2003. Sustainable consumption: a theoretical and environmental policy perspective. Society &Natural Resources 16(8):687–701.

Töller, Annette Elisabeth. 2017. Verkehrte Welt? Parteien (in) differenz in der Umweltpolitik am Beispiel der Regulierung des Frackings. Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 27(2):131–160.

Van Haute, Emilie. 2016. Green parties in Europe. London, New York: Routledge.

Van Haute, Emilie, and Caroline Close. 2019. Liberal parties in Europe. London, New York: Routledge.

Volkens, Andrea. 2007. Strengths and weaknesses of approaches to measuring policy positions of parties. Electoral Studies 26(1):108–120.

Volkens, Andrea, Tobias Burst, Werner Krause, Pola Lehmann, Theres Matthieß, Nicolas Merz, Sven Regel, Bernhard Weßels, and Lisa Zehntner. 2020. The Manifesto Project Dataset—Codebook, Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR), Version 2020a. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

Zohlnhöfer, Reimut. 2019. Parteien. In Handbuch Sozialpolitik, ed. H. Obinger and M. G. Schmidt, 139–158. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Acknowledgements

This contribution was inspired by a workshop on partisan politics in environmental policy. We want to thank the participants of this workshop for the interesting discussion and the reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

J. Pollex and L.E. Berker declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pollex, J., Berker, L.E. Parties and their environmental problem perceptions—Towards a more fundamental understanding of party positions in environmental politics. Z Vgl Polit Wiss 15, 571–591 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-022-00515-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-022-00515-x