Abstract

This paper explores the full observable delay game—which involves the timing of setting one public firm’s and one private firm’s strategic contracts’ levels and content—in a managerial mixed duopoly with a welfare-based delegation à la Nakamura (Int Rev Econ Finance 35:262–277, 2015, J Ind Compet Trade 19:235–261, 2019b, J Ind Compet Trade 19:679–737, 2019c). In this paper, we first show that both the following types of market frameworks can be equilibrium market structures: (1) a market formation in which the manager of the public firm, which has a quantity contract, is the leader and manager of the private firm, which has a price contract and is the follower, and (2) a market configuration in which the manager of the public firm, which has a quantity contract, is the follower, and the private firm, which also has a quantity contract, is the leader. Second, we demonstrate that the form of highest social welfare is achieved under market structure (2). Hence, in such a managerial mixed duopoly, from the perspective of social welfare, it is not as necessary for the relevant authority (including the government) to regulate owners’ free determination of the timing of setting public and private firms’ strategic contracts’ levels and content.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The best-known literature on firms’ internal organization includes Fershtman and Judd (1987), Sklivas (1987), and Vickers (1985). These three papers introduced managerial contracts equal to the weighted sum of each firm’s profit and its sales revenue with respect to the so-called sales (FJSV) incentive parameter. Subsequently, existing works in this field have applied the FJSV managerial delegation to several economic cases following Fershtman and Judd (1987), Sklivas (1987), and Vickers (1985), including Fershtman et al. (1991), Polo and Tedeschi (1992), Bárcena-Ruiz and Paz Espinoza (1996), Lambertini (2000a), and Lambertini (2000b). Existing research on the circumstances in which each firm’s owner (shareholder) provides his/her manager with an incentive contract can be frequently observed within works on corporate governance. Using data from Japanese firms, Kato and Rockel (1992), Kaplan (1994), Xu (2001), and Murase (1998) shed light on the relationship between managers’ salaries and their firms’ performance. More precisely, the four above-mentioned papers clarify that the salaries and bonuses of firms’ managers are positively associated with their accounting profits and stock prices; thus, their owners’ payoffs are included in their managers’ incentive contracts. For example, in the sample data, Xu (2001) used unbalanced panel data involving 690 firm years. The sample firms are 82 corporations in general and electronic machinery, listed in the first section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange, from 1983 to 1991.

See Ishida and Matsushima (2009), Matsumura (1998), and Matsumura and Kanda (2005) for detailed discussions on this topic. Moreover, the link between public and private companies facing financial problems is often seen in the real world, and firms that obtain public funds compete against purely private ones. Thus, research on mixed oligopolies has become even more vital, not only in developing countries, but also in developed nations.

Both Nakamura (2019c) and this paper analyze the full observable delay game in a managerial mixed duopoly with the welfare-based delegation and the FJSV delegation together. However, the difference between Nakamura (2019c) and this paper is that the former deals with the endogenous determination of the timing of setting both the public firm’s welfare-based incentive parameter and the private firm’s FJSV incentive parameter, while the latter considers the endogenous determination of the timing of setting their strategic contracts’ levels and content. The equilibrium market structures in both Nakamura (2019c) and this paper are common in terms of their strategic contracts’ content, namely, the q–q game and the q–p game.

Jacques (2004) and Lu (2007) slightly corrected the proposition’s content (Proposition 4.1) in relation to the equilibrium market structures, stated in the context of an entrepreneurial mixed oligopoly in quantity competition with a homogeneous good by newly adding the equilibrium market structures forgotten in Pal (1998).

Most recently, Lambertini et al. (2009) examined a linear state differential game describing an asymmetric Cournot duopoly with capacity accumulation à la Ramsey and a negative environmental (pollutive) externality (pollution), where one firm has adopted CSR, and thus includes consumer surplus and the environmental effects of production in its objective function. Thereafter, Lee and Xu (2018) scrutinized an endogenous timing game in the contexts of both private and mixed duopolies under price competition with differentiated goods in which each firm’s emission tax is imposed on the environmental externality (pollution). It was assumed that the CSR firm’s incentive delegation is equal to the weighted sum of its profit and consumer surplus with respect to its incentive parameter in Goering (2012), Goering (2014), and Kopel and Brand (2013).

In an entrepreneurial private duopoly, Sun (2013) found that the unique equilibrium structure entails simultaneous quantity competition if the goods are substitutes and simultaneous price competition if the goods are complements. In an entrepreneurial mixed duopoly, Din and Sun (2016) showed that simultaneous price competition is the singular equilibrium market structure in the first period regardless of whether the goods are substitutes or complements. In the real-world economy, mixed oligopolistic industries make it difficult to judge whether price or quantity competition should be used for the relevant theoretical analysis (e.g., hospitals, broadcasting, education). In a managerial mixed oligopoly (including such industries), when focusing on long-term decisions on the internal organization of each firm to ensure that it survives, it is important for the owner to choose each firm’s strategic contract’s content as well as (1) the timing of setting the strategic contract’s level, (2) whether the contract will be entrepreneurial or managerial, and (3) the contracts of the incentive contract (i.e., the level of the incentive parameter). In sum, long-term decisions on the internal organization of each firm by the owner as well as the timing of setting the strategic contract’s level and content should be observed in a managerial mixed duopoly (including hospitals, broadcasting, and education).

Nakamura (2019a) demonstrated that the following two equilibrium market structures are possible in the (1) full observable delay game: (1) the public firm’s owner is the follower (with its quantity contract) and the private firm’s owner is the leader (with its quantity contract) and (2) the owners of both firms use their price contracts and simultaneously set their incentive parameters in the late period. By contrast, Nakamura (2019b) revealed that the market structure in which the public firm’s manager (with her quantity contract) is the follower and the private firm’s manager (with her price contract) is the leader can become the special equilibrium market structure in the (2) full observable delay game.

As indicated by Nakamura (2019b), there is a recent example from Japan of the same managerial delegation contract being used for both a private firm and a public one via private finance initiative activities. This corresponds to the private delivery of business activities by a (local) public firm to a private one in a water supply business in Tokyo, Yokohama, and Fukushima as well as in the gas industry in Gunma. On the contrary, irrespective of such aggressive private finance initiative activities in Japan, the mixed oligopolistic situation and the public firm’s presence remain in many sectors, including financial markets and public enterprises such as the Postal Bank (the largest “bank” in the world), the Development Bank of Japan, and the Public House Loan Corporation. In these fields, it is more likely that the incentive contract between each firm’s owner and manager will differ between public and private firms. Hence, we consider the approach of Nakamura (2015, 2019c) in which the incentive contract employed in the public firm differs from that in the private firm to be meaningful.

In addition, for all four games, namely, the q–q game, the p–p game, the p–q game, and the q–p game, and from the perspective of both consumer surplus and producer surplus, we consider whether it is necessary for the relevant authority (including the government) to regulate owners’ free determination of the timing of setting public and private firms’ strategic contracts’ levels.

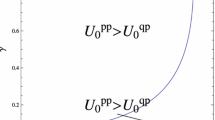

In addition, analogous to the analyses in Nakamura (2015, 2019c), the probabilities of the public and private firms’ owners choosing their quantity contracts are higher than the chances of them selecting their price contracts for any degree of homogeneity between the goods produced by both the public and the private firms. Moreover, the probability of the public firm’s owner choosing his quantity contract is higher than that of the private firm’s owner for any degree of homogeneity between the goods produced by both the public and the private firms.

In the SSws case, as shown by Nakamura (2015, 2019c), there is no equilibrium market structure for any degree of homogeneity of the goods produced by the public and private firms. Hence, we thoroughly describe the probabilities with which the public and private firms select their respective quantity contracts under a unique mixed strategy equilibrium market structure.

In this paper’s supplementary material, we present the process of deriving the market outcomes for the public and private firms for all four games in relation to the three cases as well as the concrete market outcomes (except for their incentive parameters and owners’ payoffs).

In the model of a managerial mixed duopoly with the welfare-based delegation in a public firm and the FJSV delegation in a private firm (in which the owners decide the timing of setting their strategic contracts’ levels and content), as considered in this paper, we suppose that the area of \(\delta\) is restricted to the open interval \(\left( 0, 1 \right)\). This is because firm 0’s profit is strictly positive across all four games in relation to the three cases. For the market outcomes to be strictly positive in all cases, the interval of \(\delta\), which refers to the degree of the substitutability of the goods produced by firms 0 and 1, is restricted to \(\left( 0, 1 \right)\), similar to Nakamura (2019c). This is because although firm 0’s profit is not equal to firm 0’s payoff, it would be unnatural for it to be negative or 0.

In general, consumer surplus is defined as \(CS_{ij} = \alpha \left( q_{0ij} + q_{1ij} \right) - \beta \left[ \left( q^{2}_{0ij} + 2 \delta q_{0ij} q_{1ij} + q^{2}_{1ij} \right) / 2 \right] - \left( p_{0ij} q_{0ij} + p_{1ij} q_{1ij} \right)\) and social welfare is defined as the sum of consumer and producer surpluses, namely, \(W_{ij} = CS_{ij} + PS_{ij}\), \(\left( i, j = q, p \right)\).

The symbol ws denotes the market outcomes for the three cases, namely, the simultaneous determination of firm 0’s and firm 1’s strategic contracts’ levels, SSws, and the two kinds of sequential determinations of their strategic contracts’ levels, LFws and FLws, in a managerial mixed duopoly with the welfare-based and FJSV delegations.

In this paper, the market structure is classified by the following two factors: (1) the strategic contracts employed within firms 0 and 1 (prices or quantities) and (2) the timing of setting the levels of their strategic contracts in the third stage, which is selected by their managers (the first period or the second period). See Sect. 5 for this discussion.

In “Appendix”, we present (1) both firms’ equilibrium incentive parameters and their owners’ equilibrium payoffs and (2) the ranking order of both firms’ payoffs among the three cases in the q–q game as well as their intuition.

In “Appendix”, we give (1) both firms’ equilibrium incentive parameters and their owners’ equilibrium payoffs and (2) the ranking order of both firms’ payoffs among the three cases in the p–p game in addition to their intuition.

In “Appendix”, we give (1) both firms’ equilibrium incentive parameters and their owners’ equilibrium payoffs and (2) the ranking order of both firms’ payoffs among the three cases in the p–q game in addition to their intuition.

The ranking orders of both firms’ owners show that \((p^{2}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\), \((p^{1}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\), and \((p^{2}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\) cannot dominate each other based on risk domination à la Harsanyi and Selten (1988).

In “Appendix”, we give (1) both firms’ equilibrium incentive parameters and their owners’ equilibrium payoffs and (2) the ranking order of both firms’ payoffs among the three cases in the q–p game in addition to their intuition.

Similar to Nakamura (2015, 2019c), we have \(d z^{SSws}_{0} / d \delta = 8 \delta ^3 (2 - \delta ^2) / (8 - 8 \delta ^2 + \delta ^4)^2 > 0\) and \(d z^{SSws}_{1} / d \delta = 2 \delta / (2 - \delta ^2)^2 > 0\) for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\). Thus, the probabilities of both firms’ owners choosing their quantity contracts also increase along with the rise in \(\delta\) when market competition becomes more intense in the SSws case in a managerial mixed duopoly with the welfare-based and FJSV delegations.

From the ranking orders of both firms’ owners, \((q^{1}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\) and \((q^{1}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\) cannot dominate each other based on risk domination à la Harsanyi and Selten (1988) for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

More precisely, in this paper’s supplementary material, in the LFws case, we find that \(CS^{LFws}_{qp} = CS^{LFws}_{qq} > CS^{LFws}_{pp} = CS^{LFws}_{pq}\) for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1\right)\), while \(PS^{LFws}_{pq} = PS^{LFws}_{pp} > PS^{LFws}_{qq} = PS^{LFws}_{qp}\) for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

From the ranking orders of both firms’ owners, \((q^{2}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\) and \((p^{2}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\) cannot dominate each other based on risk domination à la Harsanyi and Selten (1988) for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

In the FLws case, we find that \(CS^{FLws}_{pq} = CS^{FLws}_{qq} > CS^{FLws}_{pp} = CS^{FLws}_{qp}\) for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), while \(PS^{FLws}_{qp} = PS^{FLws}_{qq} = PS^{FLws}_{pp} = PS^{FLws}_{pq}\) for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), which are given in this paper’s supplementary material.

Similarly, the difference in the equilibrium market structures between this paper and Nakamura (2019c) is explained by the difference in the above optimal strategies for the owners of firms 0 and 1 when the strategy of the owner of their respective firm is fixed between the two papers. In particular, we focus on the following two situations:

-

1.

When \(q^{2}_{1}\) is fixed, the optimal strategies for the owner of firm 0 are \(q^{1}_{0}\), \(p^{1}_{0}\), and \(p^{2}_{0}\) in Nakamura (2019c), while the optimal strategy for the owner of firm 0 is \(p^{2}_{0}\) in this paper.

-

2.

When \(q^{2}_{0}\) is fixed, the optimal strategies for the owner of firm 1 are \(q^{1}_{1}\) and \(p^{1}_{1}\) in Nakamura (2019c), while the optimal strategy for the owner of firm 1 is \(q^{1}_{1}\) in this paper.

The above difference between the optimal strategy of firms 0 and 1 when the strategy of the owner of their respective rival firm is fixed yields the results that the equilibrium market structures in this paper are composed of \((q^{2}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\) and \((q^{1}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), while the equilibrium market structures in Nakamura (2019c) are composed of \((q^{1}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\) and \((q^{2}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\).

-

1.

In this paper’s supplementary material, we provide all the market outcomes (except for firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter in addition to their owners’ payoffs) in (1) \((q^{1}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\) and \((q^{2}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), (2) \((q^{1}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), and (3) \((q^{2}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\).

In this paper’s supplementary material, we provide all the market outcomes (except for firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter in addition to their owners’ payoffs) in (1) \((p^{1}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\) and \((p^{2}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), (2) \((p^{1}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), and (3) \((p^{2}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\).

In this paper’s supplementary material, we provide all the market outcomes (except for firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter in addition to their owners’ payoffs) in (1) \((p^{1}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\) and \((p^{2}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), (2) \((p^{1}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), and (3) \((p^{2}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\).

In this paper’s supplementary material, we provide all the market outcomes (except for firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter in addition to their owners’ payoffs) in (1) \((q^{1}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\) and \((q^{2}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), (2) \((q^{1}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), and (3) \((q^{2}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\).

In fact, as described in this paper’s supplementary material, in the q–q game, we give the concrete ranking order of producer surplus, under which producer surplus is the highest in the FLws case among all three cases for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

In fact, in the q–q game, producer surplus in the SSws case is the lowest among all three cases for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), while consumer surplus is the highest in the SSws case among all three cases for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\). These facts are given in this paper’s supplementary material in detail.

These facts can be realized from the ranking orders of consumer and producer surpluses in the p–p game, which are given in this paper’s supplementary material in detail.

A detailed discussion of this fact can be found in the relevant statements in the p–p game provided in this paper’s supplementary material.

These results are stated in this paper’s supplementary material in detail.

These results are also confirmed in this paper’s supplementary material in detail.

These results on the coincidence of the relevant ranking orders of market outcomes among all three cases can be seen in this paper’s supplementary material.

References

Bárcena-Ruiz R, Paz Espinoza M (1996) Long-term or short-term managerial contracts. J Econ Manag Strategy 5:343–359

Bárcena-Ruiz JC (2007) Endogenous timing for a mixed duopoly: price competition. J Econ 91:263–272

Bárcena-Ruiz JC, Garzón MB (2010) Endogenous timing for a mixed oligopoly with semipublic firms. Port Econ J 9:97–113

Bárcena-Ruiz JC (2013) Endogenous timing of incentive contracts in mixed markets under Bertrand competition. Manch Sch 81:340–355

Barros F (1995) Incentive schemes as strategic variables: an application to a mixed duopoly. Int J Ind Organ 13:373–386

Chirco A, Scrimitore M (2013) Choosing price or quantity? The role of delegation and network externalities. Econ Lett 121:482–486

Chirco A, Colombo C, Scrimitore M (2014) Organizational structure and the choice of price versus quantity in a mixed duopoly. Jpn Econ Rev 65:521–542

Din H-R, Sun C-H (2016) Combining the endogenous choice of timing and competition version in a mixed duopoly. J Econ 118:141–166

Dixit A (1979) A model of duopoly suggesting a theory of entry barriers. Bell J Econ 10:20–32

Fershtman C, Judd K (1987) Equilibrium incentives in oligopoly. Am Econ Rev 77:927–940

Fershtman C, Judd K, Klemperer E (1991) Observable contracts: strategic delegation and cooperation. Int Econ Rev 93:551–559

Goering GE (2012) Corporate social responsibility and marketing channel coordination. Res Econ 66:142–148

Goering GE (2014) The profit-maximizing case for corporate social responsibility in a bilateral monopoly. Manag Decis Econ 35:493–499

Hamilton JH, Slutsky SM (1990) Endogenous timing for duopoly games: Stackelberg or Cournot equilibria. Games Econ Behav 2:29–46

Harsanyi JC, Selten R (1988) A general theory of equilibrium selection in games. MIT Press, Cambridge

Ishida J, Matsushima N (2009) Should civil servants be restricted in wage bargaining? A mixed-duopoly approach. J Public Econ 93:634–646

Jacques A (2004) Endogenous timing for a mixed oligopoly: a forgotten equilibrium. Econ Lett 83:147–148

Kopel T, Brand B (2013) Socially responsible firms and endogenous choice of strategic incentives. Econ Model 29:982–989

Kaplan SN (1994) Top executive rewards and firm performance: a comparison of Japan and the United States. J Polit Econ 102:510–546

Kato T, Rockel M (1992) Experience, credential, and competition in the Japanese and U.S. managerial labor markets: evidence from the new micro data. J Jpn Int Econ 6:30–51

Lambertini L (2000a) Extended games played by managerial firms. Jpn Econ Rev 51:274–283

Lambertini L (2000b) Strategic delegation and the shape of market competition. Scott J Polit Econ 47:550–570

Lambertini L, Palestini A, Tampieri A (2009) CSR in an asymmetric duopoly with environmental externality. South Econ J 83:236–252

Lee S-H, Xu L (2018) Endogenous timing of private and mixed duopolies with emission taxes. J Econ 124:175–201

Lu Y (2007) Endogenous timing for a mixed oligopoly: another forgotten equilibrium. Econ Lett 94:226–227

Matsumura T (1998) Partial privatization in mixed duopoly. J Public Econ 70:473–483

Matsumura T, Kanda O (2005) Mixed oligopoly at free entry markets. J Econ 84:27–48

Matsumura T, Ogawa A (2010) On the robustness of private leadership in mixed duopoly. Aust Econ Pap 49:149–160

Matsumura T, Ogawa A (2012) Price versus quantity in a mixed duopoly. Econ Lett 116:174–177

Matsumura T, Ogawa A (2014) Corporate social responsibility or payoff asymmetry? A study of an endogenous timing game. South Econ J 81:457–473

Méndez-Naya J (2015) Endogenous timing for a mixed duopoly model. J Econ 116:47–61

Murase H (1998) Equity ownership and the determinant of managers bonuses in Japanese firm. Jpn World Econ 10:321–331

Nakamura Y (2015) Endogenous choice of strategic incentives in a mixed duopoly with a new managerial delegation contract for the public firm. Int Rev Econ Finance 35:262–277

Nakamura Y (2018a) Endogenous timing of incentive contracts in a managerial oligopoly focusing on asymmetric strategic contracts and the relation between each firm’s goods. Mimeograph

Nakamura Y (2018b) Combining the endogenous choice of the timing of setting the incentive parameters and content of strategic contracts in a managerial duopoly. Mimeograph

Nakamura Y (2019a) Combining the endogenous choice of the timing of setting incentive parameters and the contents of strategic contracts in a managerial mixed duopoly. Int Rev Econ Finance 59:207–233

Nakamura Y (2019b) Combining the endogenous choice of the timing of setting the levels of strategic contracts and their contents in a managerial mixed duopoly. J Ind Compet Trade 19:235–261

Nakamura Y (2019c) Endogenous choice of the timing of setting incentive parameters and the strategic contracts in a managerial mixed duopoly with a welfare-based delegation contract and a sales delegation contract. J Ind Compet Trade 19:679–737

Nakamura Y, Inoue T (2007) Endogenous timing for a mixed duopoly: the managerial delegation case. Econ Bull 12(27):1–7

Nakamura Y, Inoue T (2009) Endogenous timing for a mixed duopoly: price competition with managerial delegation. Manag Decis Econ 30:325–333

Nishimori A, Ogawa H (2005) Long-term and short-term contract in a mixed market. Aust Econ Pap 44:275–289

Pal D (1998) Endogenous timing for a mixed oligopoly. Econ Lett 61:181–185

Polo M, Tedeschi P (1992) Managerial contracts, collusion and mergers. Ricerche Economiche 46:281–302

Sadanand A, Sadanand V (1996) Firm scale and the endogenous timing of entry: a choice between commitment and flexibility. J Econ Theory 70:516–530

Singh N, Vives X (1984) Price and quantity competition in a differentiated duopoly. RAND J Econ 15:546–554

Sklivas SD (1987) The strategic choice of management incentives. RAND J Econ 18:452–458

Sun CH (2013) Combining the endogenous choice of price/quantity and timing. Econ Lett 120:364–368

Vickers J (1985) Delegation and the theory of the firm. Econ J 95:138–147

White MD (2001) Managerial incentives and the decision to hire managers in markets with public and private firms. Eur J Polit Econ 17:877–896

Xu P (2001) Executive salaries as tournament prizes and executive bonuses as managerial incentives in Japan. J Jpn Int Econ 11:319–346

Funding

This research was supported by the Seimeikai Foundation (No. 16-002), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (No. 16K03665), and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (No. 16H03624) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 q–q game

Here, we give both firms’ equilibrium incentive parameters as well as their owners’ payoffs in the thin q–q game.

1.1.1 SSws case

In \((q^{1}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\) and \((q^{2}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter are given as follows:Footnote 34

Thus, in \((q^{1}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\) and \((q^{2}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), firm 0’s owner makes his manager more aggressive than the sole welfare maximizer, while firm 1’s owner makes his manager more aggressive than the sole profit maximizer. Then, in \((q^{1}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\) and \((q^{2}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), both firms’ owners’ payoffs are given as follows:

1.1.2 LFws case

In \((q^{1}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter are given as follows:

Thus, in \((q^{1}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), firm 0’s owner makes his manager the sole welfare maximizer, while firm 1’s owner makes his manager more aggressive than the sole profit maximizer. Then, in \((q^{1}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), both firms’ owners’ payoffs are given as follows:

1.1.3 FLws case

In \((q^{2}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\), firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter are given as follows:

Thus, in \((q^{2}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\), for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), firm 0’s owner makes his manager the sole welfare maximizer, while firm 1’s owner makes his manager more aggressive than the sole profit maximizer. Then, in \((q^{2}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\), both firms’ owners’ payoffs are given as follows:

1.2 p–p game

Here, we give both firms’ equilibrium incentive parameters as well as their owners’ payoffs in the thin p–p game.

1.2.1 SSws case

In \((p^{1}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\) and \((p^{2}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter are given as follows:Footnote 35

Thus, in \((p^{1}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\) and \((p^{2}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), firm 0’s owner makes his manager the sole welfare maximizer, while firm 1’s owner makes his manager less aggressive than the sole profit maximizer. Then, in \((p^{1}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\) and \((p^{2}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), both firms’ owners’ payoffs are given as follows:

1.2.2 LFws case

In \((p^{1}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter are given as follows:

Thus, in \((p^{1}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), firm 0’s owner makes his manager the sole welfare maximizer, while firm 1’s owner makes his manager less aggressive than the sole profit maximizer. Then, in \((p^{1}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), both firms’ owners’ payoffs are given as follows:

1.2.3 FLws case

In \((p^{2}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\), firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter are given as follows:

Thus, in \((p^{2}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\), for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), firm 0’s owner makes his manager more aggressive than the sole welfare maximizer, while firm 1’s owner makes his manager the sole profit maximizer. Then, in \((p^{2}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\), both firms’ owners’ payoffs are given as follows:

1.3 p–q game

Here, we give both firms’ equilibrium incentive parameters as well as their owners’ payoffs in the thin p–q game.

1.3.1 SSws case

In \((p^{1}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\) and \((p^{2}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter are given as follows:Footnote 36

Thus, in \((p^{1}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\) and \((p^{2}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), firm 0’s owner makes his manager more than the sole welfare maximizer, while firm 1’s owner makes his manager the sole profit maximizer. Then, in \((p^{1}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\) and \((p^{2}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), both firms’ owners’ payoffs are given as follows:

1.3.2 LFws case

In \((p^{1}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter are given as follows:

Thus, in \((p^{1}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), firm 0’s owner makes his manager the sole welfare maximizer, while firm 1’s owner makes his manager less aggressive than the sole profit maximizer. Then, in \((p^{1}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), both firms’ owners’ payoffs are given as follows:

1.3.3 FLws case

In \((p^{2}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\), both firms’ FJSV incentive parameters are given as follows:

Thus, in \((p^{1}_{0}, q^{2}_{1})\), for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), firm 0’s owner makes his manager less aggressive than the sole welfare maximizer, while firm 1’s owner makes his manager the sole profit maximizer. Then, in \((p^{2}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\), both firms’ owners’ payoffs are given as follows:

1.4 q–p game

Here, we give both firms’ equilibrium incentive parameters as well as their owners’ payoffs in the thin q–p game.

1.4.1 SSws case

In \((q^{1}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\) and \((q^{2}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter are given as follows:Footnote 37

Thus, in \((q^{1}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\) and \((q^{2}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), firm 0’s owner makes his manager more aggressive than the sole welfare maximizer, while firm 1’s owner makes his manager the sole profit maximizer. Then, in \((q^{1}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\) and \((q^{2}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), both firms’ owners’ payoffs are given as follows:

1.4.2 LFws case

In \((q^{1}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter are given as follows:

Thus, in \((q^{1}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), firm 0’s owner makes his manager the sole welfare maximizer, while firm 1’s owner makes his manager more aggressive than the sole profit maximizer. Then, in \((q^{1}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\), both firms’ owners’ payoffs are given as follows:

1.4.3 FLws case

In \((q^{2}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\), firm 0’s welfare-based incentive parameter and firm 1’s FJSV incentive parameter are given as follows:

Thus, in \((q^{2}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\), for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), firm 0’s owner makes his manager more aggressive than the sole welfare maximizer, while firm 1’s owner makes his manager the sole profit maximizer. Then, in \((q^{2}_{0}, p^{1}_{1})\), both firms’ owners’ payoffs are given as follows:

1.5 Ranking orders of both firms’ owners’ payoffs among the three cases in the q–q game

In the q–q game, we obtain the following ranking orders of both firms’ owners’ payoffs among the three cases:

-

1.

\(U^{FLws}_{0qq}> U^{SSws}_{0qq} > U^{LFws}_{0qq}\) if \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

-

2.

\(U^{FLws}_{1qq}> U^{LFws}_{1qq} > U^{SSws}_{1qq}\) if \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

In the q–q game, social welfare (which equals firm 0’s owner’s payoff) is the highest in the FLws case, since producer surplus is sufficiently high in the FLws case for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).Footnote 38 In the q–q game, consumer surplus is sufficiently high in the SSws case for any \(\left( 0, 1 \right)\), while producer surplus is sufficiently low for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\). Then, since the latter effect is stronger than the former effect on the ranking order of social welfare (which equals firm 0’s owner’s payoff), social welfare is higher in the SSws case than in the FLws case for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).Footnote 39 Thus, in the q–q game, the ranking order of social welfare is mainly explained not by that of consumer surplus, but by that of producer surplus for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

By contrast, in the q–q game, firm 1’s profit (which equals firm 1’s payoff) is the lowest for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), since firm 1’s price in the SSws case is the lowest in the SSws case among all three cases for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\). Meanwhile, firm 1’s profit (which equals its owner’s payoff) is not the highest in the LFws case among all three cases, since firm 1’s quantity is the lowest in the LFws case among all three cases. As a result, firm 1’s profit (which equals its owner’s payoff) is the highest in the FLws case for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\) among all three cases, since firm 1’s quantity is the highest, and firm 1’s price is the second highest, in the FLws case for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\) among all three cases.

1.6 Ranking orders of both firms’ owners’ payoffs among the three cases in the p–p game

In the p–p game, we obtain the following ranking orders of both firms’ owners’ payoffs among the three games:

-

1.

-

(a)

\(U^{LFws}_{0pp} \ge U^{FLws}_{0pp} > U^{SSws}_{0pp}\) if \(\delta \in \left( 0, 0.942809 \right]\).

-

(b)

\(U^{FLws}_{0pp}> U^{LFws}_{0pp} > U^{SSws}_{0pp}\) otherwise.

-

(a)

-

2.

\(U^{LFws}_{1pp}> U^{SSws}_{1pp} > U^{FLws}_{1pp}\) if \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1\right)\).

In the p–p game, social welfare (which equals firm 0’s owner’s payoff) is the highest in the LFws case among all three cases, since consumer surplus in the LFws case is sufficiently high when \(\delta \in \left( 0, 0.510794 \right]\), while social welfare is the highest in the FLws case among all three cases, since consumer surplus in the FLws case is sufficiently high when \(\delta \in \left[ 0.942809, 1 \right)\).Footnote 40 Thus, when \(\delta \in \left( 0.510794, 0.942809 \right)\), although social welfare is the highest in the LFws case among all three cases, its fact is not supported by the ranking orders of consumer and producer surpluses. Considering that both consumer surplus and producer surplus are the second highest in the LFws case when \(\delta \in \left( 0.510794, 0.942809 \right)\), the fact that social welfare is the highest in the LFws case is explained. By contrast, in the p–p game, the ranking order of firm 1’s profit (which equals its owner’s payoff) coincides with that of firm 1’s quantity.Footnote 41

1.7 Ranking orders of both firms’ owners’ payoffs among the three cases in the p–q game

In the p–q game, we obtain the following ranking orders of both firms’ owners’ payoffs among the three games:

-

1.

\(U^{SSws}_{0pq} = U^{FLws}_{0pq} > U^{LFws}_{0pq}\) if \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

-

2.

\(U^{LFws}_{1pq} > U^{SSws}_{1pq} = U^{FLws}_{1pq}\) if \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

In the p–q game, the ranking order of social welfare (which equals firm 0’s owner’s payoff) coincides with that of consumer surplus for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), while that of social welfare is the reverse of that of its price.Footnote 42 By contrast, the ranking order of firm 1’s profit (which equals its owner’s payoff) is the same as that of firm 1’s price and producer surplus for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).Footnote 43

1.8 Ranking orders of both firms’ owners’ payoffs among the three cases in the q–p game

In the q–p game, we obtain the following ranking orders of both firms’ owners’ payoffs:

-

1.

\(U^{LFws}_{0qp} > U^{SSws}_{0qp} = U^{FLws}_{0qp}\) if \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

-

2.

\(U^{LFws}_{1qp} > U^{SSws}_{1qp} = U^{FLws}_{1qp}\) if \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

In the q–p game, the ranking order of social welfare (which equals firm 0’s owner’s payoff) coincides with those of both firms’ quantities and consumer surplus for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\), while the ranking order of firm 1’s profit (which equals firm 1’s owner’s payoff) is the same as that of firm 1’s quantity for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).Footnote 44

1.9 Proof of Proposition 1

The proof of this proposition is composed of the following eight claims on the optimal strategy of firm i provided that the strategy of its rival, firm j, is fixed, \(\left( i, j = 0, 1; i \ne j \right)\).

Claim 1

For a given firm 1’s choice \(q^{1}_{1}\): \(U^{FLws}_{0qq} = U^{FLws}_{0pq} = U^{SSws}_{0pq} > U^{SSws}_{0qq}\)for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

The first equality is derived from Lemma 6, the second equality is derived from Lemma 3, and the third inequality is derived from Result 1. Thus, when firm 1’s owner’s strategy is \(q^{1}_{1}\), firm 0’s optimal strategy is \(q^{2}_{0}\), \(p^{1}_{0}\), or \(p^{2}_{0}\). In this case, firm 0’s owner is indifferent in terms of choosing between \(q^{2}_{0}\), \(p^{1}_{0}\), and \(p^{2}_{0}\).

Claim 2

For a given firm 1’s choice \(q^{2}_{1}\): \(U^{SSws}_{0pq}> U^{SSws}_{0qq}> U^{LFws}_{0qq} > U^{LFws}_{0pq}\)for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

The first inequality is derived from Result 1, the second inequality is derived from Lemma 1, and the third inequality is derived from Lemma 5. Thus, when firm 1’s owner’s strategy is \(q^{2}_{1}\), firm 0’s owner’s optimal strategy is \(p^{2}_{0}\).

Claim 3

For a given firm 1’s choice \(p^{1}_{1}\): \(U^{SSws}_{0qp} = U^{FLws}_{0qp} = U^{FLws}_{0pp} > U^{SSws}_{0pp}\)for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

When firm 1’s strategy is \(p^{1}_{1}\), the first equality is derived from Lemma 4, the second equality is derived from Lemma 6, and the third inequality is derived from Lemma 2. Thus, when firm 1’s owner’s strategy is \(p^{1}_{1}\), firm 0’s owner’s optimal strategy is \(q^{1}_{0}\), \(q^{2}_{0}\), or \(p^{2}_{0}\). In this case, firm 0’s owner is indifferent in terms of choosing between \(q^{1}_{0}\), \(q^{2}_{0}\), and \(p^{2}_{0}\).

Claim 4

For a given firm 1’s choice \(p^{2}_{1}\):

-

1.

\(U^{LFws}_{0qp}> U^{SSws}_{0qp} \ge U^{LFws}_{0pp} > U^{SSws}_{0pp}\) if \(\delta \in \left[ 0.942809, 1 \right)\).

-

2.

\(U^{LFws}_{0qp}> U^{LFws}_{0pp}> U^{SSws}_{0qp} > U^{SSws}_{0pp}\)otherwise.

When firm 1’s strategy is \(p^{2}_{1}\), although the ranking order of firm 0’s owner’s payoff depends on the level of \(\delta\), firm 0’s owner’s optimal strategy is unique for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\) as follows:

-

1.

\(U^{LFws}_{0qp} > U^{SSws}_{0qp}\) is derived from Lemma 4.

-

2.

\(U^{LFws}_{0pp} > U^{SSws}_{0pp}\) is derived from Lemma 2.

-

3.

\(U^{LFws}_{0qp} > U^{LFws}_{0pp}\) is derived from Lemma 5.

-

4.

\(U^{SSws}_{0qp} > U^{SSws}_{0pp}\) is derived from Result 1.

In addition, from easy calculations, \(U^{SSws}_{0qp} \ge U^{LFws}_{0pp}\) if \(\delta \in \left( 0, 0.942809 \right]\), while \(U^{LFws}_{0pp} > U^{SSws}_{0qp}\) otherwise. Thus, when firm 1’s owner’s strategy is \(p^{2}_{1}\), firm 0’s owner’s optimal strategy is \(q^{1}_{0}\).

Claim 5

For a given firm 0’s choice \(q^{1}_{0}\): \(U^{LFws}_{1qq} = U^{LFws}_{1qp}> U^{SSws}_{1qp} > U^{SSws}_{1qq}\)for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

The first equality is derived from Lemma 5, the second inequality is derived from Lemma 4, and the third inequality is derived from Result 1. Thus, when firm 0’s owner’s strategy is \(q^{1}_{0}\), firm 1’s owner’s optimal strategy is \(q^{2}_{1}\) or \(p^{2}_{1}\). In this case, firm 1’s owner is indifferent in terms of choosing between choosing \(q^{2}_{1}\) and \(p^{2}_{1}\).

Claim 6

For a given firm 0’s choice \(q^{2}_{0}\): \(U^{FLws}_{1qq}> U^{SSws}_{1qq} > U^{SSws}_{1qp} = U^{FLws}_{1qp}\)for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

The first inequality is derived from Lemma 1, the second inequality is derived from Result 1, and the third inequality is derived from Lemma 4. Thus, when firm 0’s owner’s strategy is \(q^{2}_{0}\), firm 0’s owner’s optimal strategy is \(q^{1}_{1}\). Firm 1’s owner is indifferent in terms of choosing \(q^{1}_{1}\).

Claim 7

For a given firm 0’s choice \(p^{1}_{0}\): \(U^{LFws}_{1pq} = U^{LFws}_{1pp}> U^{SSws}_{1pp} > U^{SSws}_{1pq}\)for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

The first equality is derived from Lemma 5, the second inequality is derived from Lemma 2, and the third inequality is derived from Result 1. Thus, when firm 0’s owner’s strategy is \(p^{1}_{0}\), firm 1’s owner’s optimal strategy is \(q^{1}_{1}\) or \(p^{1}_{1}\).

Claim 8

For a given firm 0’s choice \(p^{2}_{0}\): \(U^{SSws}_{1pp}> U^{SSws}_{1pq} = U^{FLws}_{1pq} > U^{FLws}_{1pp}\)for any \(\delta \in \left( 0, 1 \right)\).

The first inequality is derived from Result 1, the second equality is derived from Lemma 3, and the third inequality is derived from Lemma 6. Thus, when firm 0’s strategy is \(p^{2}_{0}\), firm 1’s owner’s optimal strategy is \(p^{2}_{1}\).

In sum, taking firm i’s owner’s optimal strategy into account provided that firm j’s owner’s strategy is given, the market structure under which both firms’ owners’ optimal strategies coincide are observed in the equilibrium as the two pairs of their strategies: (1) \(\left( q^{2}_{0}, q^{1}_{1} \right)\) and (2) \(\left( q^{1}_{0}, p^{2}_{1} \right)\). This implies that both (1) \((q^{2}_{0}, q^{1}_{1})\) and (2) \((q^{1}_{0}, p^{2}_{1})\) can be seen as equilibrium market structures, \(\left( i, j = 0, 1; i \ne j \right)\). \(\square\)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nakamura, Y. Endogenously choosing the timing of setting strategic contracts’ levels and content in a managerial mixed duopoly with welfare-based and sales delegation contracts. Int Rev Econ 67, 363–402 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-020-00347-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-020-00347-9

Keywords

- Cournot competition

- Bertrand competition

- Endogenous timing of the levels of strategic contracts

- Mixed duopoly

- Welfare-based delegation

- Sales delegation