Abstract

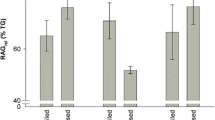

The aim of the research was to determine contributions of moisture and carbohydrate digestibility to the glycemic impact of potatoes. Five potato cultivars, including low dry matter, low glycemic index ‘Almera’ and high dry matter ‘Moonlight’ were boiled and subsamples taken for dry matter and simulated digestion in vitro. Digestion-time profiles of the different cultivars were of very similar shape, although the quantity of carbohydrate released differed between cultivars. ‘Moonlight’ gave the highest rapidly available (20 min) carbohydrate (16.2 ± 0.9 g/100 g) and ‘Almera’ the lowest (11.1 ± 2 g/100 g). The cultivars also differed in dry matter content, ‘Almera’ having the lowest (14.4 ± 0.4%) and ‘Moonlight’ the highest (23.3 ± 0.5%). However, adjusted to an equivalent 20% dry matter, digestion profiles of all cultivars were almost identical. We conclude that values reflecting solely the digestibility of carbohydrate in potatoes cannot be accurately or easily used by consumers to guide intakes of potato in terms of customarily consumed portions, for blood glucose management. Taking into account water content and serving size, glycemic impact per standard serving of potato was moderate compared with other starchy foods.

Resumen

El objetivo de esta investigación fue determinar las contribuciones de humedad y digestibilidad de carbohidratos en el impacto glicémico de las papas. Se hirvieron cinco variedades de papa, incluyendo “Almera”, de baja materia seca y bajo índice glicémico, y “Moonlight”, alta en materia seca, y se tomaron submuestras para materia seca y digestión simulada in vitro. Los perfiles de tiempo de digestión de las diferentes variedades fueron muy similares, aunque la cantidad de carbohidratos liberados difirieron entre variedades. “Moonlight” dio los carbohidratos mas altos en rapidez de disponibilidad (20 min, 16.2 ± 0.9 g/100 g), y “Almera” los mas bajos (11.1 ± 2 g/100 g). Las variedades también difirieron en el contenido de materia seca, “Almera” tuvo el mas bajo (14.4 ± 0.4%) y “Moonlight” el mas alto (23.3 ± 0.5%). No obstante, ajustados al equivalente del 20 % de materia seca, los perfiles de digestión de todas las variedades fueron casi idénticos. Concluimos que los valores que reflejan únicamente la digestibilidad de carbohidratos en papa no pueden ser usados con precisión o facilidad por los consumidores para guiar la ingestión de papa en términos de porciones consumidas rutinariamente, para el manejo de glucosa en la sangre. Tomando en consideración el contenido de agua y el tamaño de la porción, el impacto glicémico por porción estándar de papa fue moderado comparado con otros alimentos con almidón.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barclay, A. 2008. In search of lower GI potatoes. GI News The official glycaemic index newsletter.

Brand Miller, J., K. Foster-Powell, S. Colagiuri, and A. Leeds. 1998. The G.I. Factor, 2nd ed. Rydalmere: Hodder & Stoughton.

Brouns, F., I. Bjorck, K. Frayn, A. Gibbs, V. Lang, G. Slama, and T. Wolever. 2005. Glycaemic index methodology. Nutrition Research Reviews 18: 1–28.

Burton, P., and J. Lightowler. 2006. Influence of bread volume on glycaemic response and satiety. British Journal of Nutrition 96: 877–882.

Englyst, H.N., and G.J. Hudson. 1987. Colorimetric method for routine analysis of dietary fibre as non-starch polysaccharides. A comparison with gas-liquid chromatography. Food Chemistry 24: 63–76.

FDA(US). 2005. Reference amounts customarily consumed per eating occasion. In: Code of Federal Regulations: Title 21- Food and Drugs, Vol. 101.12, pp. 52–61.

Foster-Powell, K., S.H.A. Holt, and J.C. Brand-Miller. 2002. International table of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2002. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 76: 5–56.

Hand, J. 2008. New spud chips away at diabetes and in-crop water use. Fairfax Media. http://theland.farmonline.com.au/news/nationalrural/horticulture/vegetables/new-spud-chips-away-at-diabetes-and-incrop-water-use/1367625.aspx accessed 11 August 2011.

Henry, C.J.K., H. Lightowler, C.M. Strik, H. Renton, and S. Hails. 2005. Glycemic index and glycemic load values of commercially available products in the UK. British Journal of Nutrition 94: 922–930.

Henry, C.J.K., H. Lightowler, L.M. Dodwell, and J.M. Wynne. 2007. Glycemic index and glycemic load values of commercially available products in the UK. British Journal of Nutrition 98: 147–153.

Jenkins, D.J., T.M.S. Wolever, R.H. Taylor, H. Barker, H. Fielden, J.M. Baldwin, A.C. Bowling, H.C. Newman, and A.L. Jenkins. 1981. Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 34: 362–366.

Monro, J.A., and S. Mishra. 2010a. Database values for food-based dietary control of glycaemia. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 23: 406–410.

Monro, J.A., and S. Mishra. 2010b. Glycemic impact as a property of foods is accurately measured by an available carbohydrate method that mimics the glycemic response. Journal of Nutrition 140: 1328–1334.

Monro, J.A., and M. Shaw. 2008. Glycaemic impact, glycemic glucose equivalents, glycemic index and glycemic load: definitions, distinctions and implications. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 87(suppl): 237S–243S.

Monro, J.A., S. Mishra, and B. Venn. 2010. Baselines representing blood glucose clearance improve in vitro prediction of the glycemic impact of customarily consumed food quantities. British Journal of Nutrition 103: 295–305.

Sievenpiper, J.L., R.A. Mendelson, V. Vuksan, C. Bruce-Thompson, and E.Y.Y. Wong. 1998. Effect of meal dilution on the postprandial glycemic response. Diabetes Care 21: 711–716.

Soh, N., and J. Brand Miller. 1999. The glycaemic index of potatoes: the effect of variety, cooking method and maturity. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 53: 249–254.

University of Florida. 2004, June 8. New Low-carb Potato To Debut In January. ScienceDaily. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2004/06/040608065835.htm accessed Retrieved July 11 2012.

van Kempen, T.A.T.G., P.R. Regmi, J.J. Matte, and R.T. Zijlstra. 2010. In Vitro Starch Digestion Kinetics, Corrected for Estimated Gastric Emptying, Predict Portal Glucose Appearance in Pigs. Journal of Nutrition 140: 1227–1233.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by Trimark varieties. JAM and SM have no conflict of interest. P. Neilson is a member of Trimark varieties.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mishra, S., Monro, J. & Neilson, P. Starch Digestibility and Dry Matter Roles in the Glycemic Impact of Potatoes. Am. J. Potato Res. 89, 465–470 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12230-012-9269-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12230-012-9269-9