Abstract

Create and evaluate the psychometric properties of the Quality of Life in the Neighborhood Questionnaire for Children 8 to 10 years of Age (QoL-N-Kids 8–10). The present study was conducted in a medium-sized city in southeastern Brazil with children at four public schools and one private school. The study involved three phases: a) generation and validation of the content of the items through a qualitative study and expert panel (n = 8); b) face validity through a pilot study and interviews with children (n = 30); and c) application of the final version (n = 261) for the evaluation of internal consistency, temporal stability, construct validity and discriminant validity. All statistical tests applied during this step were interpreted considering a 5% significance level. Among the 56 items generated, 38 were maintained in the scale and submitted to face validation. In this phase, the children suggested the inclusion of an additional item, resulting in a measure with 39 items. The questionnaire was submitted to reliability tests (Cronbach’s alpha) and exploratory factor analysis, leading to a questionnaire with 27 items distributed among five domains. The measures exhibited good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.805) and good test–retest reliability (weighted Kappa = 0.305 to 0.724; intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.917). Regarding discriminant validity, differences between groups (p < 0.001) were found for sex, age, income and place of residence. The QoL-N-Kids 8–10 instrument exhibited satisfactory psychometric properties and has potential for the assessment of neighborhood quality of life in children eight to ten years of age.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The World Health Organization conceives quality of life “QoL” as “individuals’ perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” (WHOQOL, 1995). Although this concept has been widely investigated in the scientific literature, there seems to be no consensus on the construct for the child population (Wallander & Koot, 2016; Wallander et al., 2001). Nonetheless, there is agreement that at least two aspects should be considered when evaluating QoL: subjectivity and multidimensionality (Wallander & Koot, 2016).

Subjectivity ensures the evaluation of QoL based the perspective of the individual and the recognition of multidimensionality enables understanding QoL as a global construct that considers all relevant dimensions of life (Wallander & Koot, 2016; Wallander et al., 2001). The literature offers different theoretical positions on the most relevant domains to children’s lives (Casas, 2016). In an attempt to systematize these domains from the perspectives of children, that is from their subjectivity, Carrillo et al. (2021) evaluated qualitative studies that explored children’s views on wellbeing and identified five dimensions that constitute this construct: a positive notion of oneself, good treatment and support relations, recognition, significant activities and contextual aspects. Thus, the evaluation of QoL goes beyond negative and performance indicators of physical, social and psychological aspects (Wallander & Koot, 2016), that have been widely explored in generic and specific measures of QoL, especially health-related QoL measures (Rajmil et al., 2012; Solans et al., 2008; Wallander & Koot, 2016).

Recent studies (Carrillo et al., 2021; Gómez et al., 2017; Ferreira Lima & Araújo de Morais, 2018) point out that QoL researchers should consider different contextual aspects related to the wellbeing of children. According to the Bronfenbrenner’s ecological approach, children may be in various contexts, which are classified on four levels depending on the proximity to their daily lives (microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem and macrosystem). The microsystem is the closest environment to the child and includes the family, school and neighborhood – places characterized by their physical, social and symbolic aspects as well as the inclinations, resources and demands of the individuals involved (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Poletto & Koller, 2008).

The relationship between microsystems and children’s wellbeing has been explored in the literature. In a multicenter study involving more than ten countries, Lawler et al. (2017) found that the school environment and neighborhood are strong predictors of wellbeing for children. In South America, studies conducted with children in Chile (Gómez et al., 2017) and Brazil (Abreu et al., 2016) also found associations between subjective wellbeing and the living environment (neighborhood and school) of children.

Although these aspects are relevant to QoL and should be considered during the development of indicators (Carrillo et al., 2021), few QOL measures, whether related to health or subjective wellbeing, have explored the microsystems of children, particularly the neighborhood (Solans et al., 2008; Rjamil et al., 2010; Bedin & Sarriera, 2014; Casas, 2016; Wallander & Koot, 2016). In a systematic review of health-related QoL measures for children and adolescents, performed by Solans et al. (2008), it is possible to see found that only six of the total of 30 total generic instruments identified included an “environment” domain (QUALIN, KIDSCREEN, QOLP-AV, TPQOL, TQOLQA and YQOL). Among these instruments, the majority were designed for young children or teenagers, with the exception Kidscreen, which targets the six-to-ten-year-old age group and addresses the school environment. Among the various scales for assessing child wellbeing identified in the literature (Bedin & Sarriera, 2014; Casas, 2016), the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scales (MSLSS) proposed by Huebner (1994) for preadolescent (third to eight grades) stands out for considering the child's living environment. Another measure identified in the literature that addresses the neighborhood environment is the C-QoL (Jirojanakul & Skevington, 2000), which was adapted from the WHOQOL, a QoL measure created for adults (WHO, 1998).

Although these measures are important and directed at the child population, the items and domains were created considering the reviews of the literature (Huebner, 1994), opinions of parents (Jirojanakul & Skevington, 2000) and specialists (Huebner, 1994) or based on questionnaires created for adults (Jirojanakul & Skevington, 2000). The participation of children was limited to pilot interviews (Huebner, 1994) or focus groups (Jirojanakul & Skevington, 2000) to determine their understanding of the items. In contrast, the studies did not mention that the perceptions of children regarding what constitutes QoL have been explored in this process (Huebner, 1994; Jirojanakul & Skevington, 2000).

The scarcity of instruments designed to measure the QoL of children from their perspective of QoL and in their different contexts is incomprehensible. The recognition of children as social subjects and the assurance of their right to express their opinions on issues that affect them are expressed in the Children’s Rights Convention (Brasil, 1990) and have been a guideline for administrators to rethink the services, equipment and QoL provided to the child population (UNICEF, 2022).

Children are capable of contributing thoughts and experiences that go beyond the adult imagination and can therefore make significant, valuable contributions regarding issues that affect their lives (Ergler et al., 2015). International studies in the field of urban planning have reported the perception of children on characteristics regarding their neighborhoods and cities. In the study conducted by Ergler et al. (2015), children three to five years of age stated that a good city should have security and access to public spaces that favor interactions with friends and family. In a study conducted with children nine to 12 years of age, Carroll et al. (2015) found that the presence of places to play, living near friends and the proximity to amenities in neighborhoods are characteristics this group appreciates. In contrast, the children did not appreciate places in the neighborhood with graffiti, rubbish, excessive noise, violence and dense traffic. Malone (2013) reported that children five to ten years of age recognized peace and quiet as well as accessibility to parks and nature as positive characteristics. Moreover, the children stated that their favorite activities involved sports, physical activity, games with others and interactions with animals and nature. Based on these concepts, it would be possible to create better environments that contribute to the health and wellbeing of children (Carroll et al., 2015; Derr & Tarantini, 2016; Ergler et al., 2015; Malone, 2013).

Considering the importance of the environment to QoL, the capacity of children to express their opinions on the living environments, the scarcity of instruments that explore this domain and the need to recognize children as social actors capable of contributing to their lives, Oliveira et al. (2020) proposed the creation of a novel QoL measure that considers the perceptions of children regarding the neighborhood in which they live. The first step of this project was to conduct a qualitative study on the perceptions of Brazilian children regarding QoL considering their living environment. This study ensured the subjectivity of the construct and enabled the development of a conceptual model that encompassed all features of the environment that are important to the QoL of the children studied. Two major topics emerged from the content analysis: physical environment and social environment. The first included necessities for living in a community, such as housing, places for recreation, essential services and natural elements. The second involved relationships with family and friends. The social and physical environments were perceived interdependently, that is, any change in either of these aspects can affect children’s QoL. (Oliveira et al., 2020).

Continuing this research (Oliveira et al., 2020), the aim of the present study was to describe the subsequent steps in the creation and validation of an assessment tool capable of measuring aspects of QoL in the neighborhood in which children live.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

A methodological study was conducted using an exploratory sequential mixed method with a qualitative-quantitative approach (Creswell, 2010). The creation and validation of the instrument was based on the steps proposed by Artino Jr. et al. (2014) and organized into three phases (Moreno Sancho et al., 2020), as shown in Fig. 1.

2.2 Study Location and Participants

Different samples were used for each phase of the study. In phase 1 (initial development of questionnaire), the sample of the expert panel consisted of ten researchers from different fields (health, communications and education) with experience in QoL, child health and the creation of assessment tools.

Phases 2 and 3 were carried out in urban areas of a medium-sized city in southeastern Brazil. The children who participated in these phases were recruited from four public schools and one private school in the city and were in the early years of elementary school. The number of schools was defined based on the proportionality of children enrolled in the public system (90%) and private system (10%) of the city (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE – Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics], 2019). The schools were selected based geographic location (city center and district) (IBGE, 2019) to ensure that children from different neighborhoods participated in the study and socioeconomic status of the school, which was determined using the Indicator of Socioeconomic Level of Basic Education Schools (Brasil, 2014), ensuring the variability of the samples with regards to this variable.

In phase 2, a pilot study (face validation) was conducted with a sample of 30 children (Artino Jr. et al., 2014). Two children from each age group (eight, nine and ten years) were selected from each school (public schools and private school) using a convenience sampling method.

In phase 3, the instrument was administered to a sample of 293 children, eight to ten years of age, from the public schools to evaluate the psychometric properties of the final questionnaire (39 items). This sample was obtained considering an acceptable proportion of six participants for each item on the questionnaire (6:1) (Anthoine et al., 2014) and a 20% dropout rate. To maintain the variability of the sample, the number of children to be recruited from each school was defined based on the proportionality of children enrolled in each institution and each age group. All children who were invited and authorized to participate in this phase of the study were part of this convenience sample.

Children from the public schools were recruited for phase 3 from November 2019 to February 2020. The children from the private school could not participate in this phase, because at the time of recruitment (March and April 2020), the city had decreed the suspension of all classes due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Santa Luzia, 2020), making it impossible to administer the questionnaire.

2.3 Phase 1 – Initial Development of Questionnaire: Generation of Items and Expert Panel

This phase consisted of the generation of the items to compose a self-administered questionnaire directed at children eight to ten years of age. The minimum age of eight years was defined due to the fact that this is the threshold age for Brazilian students to be literate (Brasil, 2007a) and, therefore, we considered most children at this age to be able to complete the questionnaire. The maximum age of ten years was established to maintain the samples in the same schools, as this is the regular age for the conclusion of the first cycle of elementary school: Grades 1 to 5 (Brasil, 1996).

2.4 Generation of Items

The content of the items proposed for the instrument was built from the results of qualitative research by Oliveira et al. (2020). The important features to have in an environment with QoL and the language used by the children in their discourses were preserved. In the drafting of the items, the researchers took care to cover the two major topics that emerged from the qualitative study: the physical environment, including the necessities for living in a community, such as housing, places of recreation, essential services and natural elements; and the social environment, which includes relationships with family and friends (Oliveira et al., 2020).

At five consecutive face-to-face meetings, the researchers created, discussed, rewrote and revised the proposed items. At the end of this process, a preliminary instrument with 56 items was obtained. The researchers also created a three-point response scale for each item measuring the frequency (never/sometimes/always) or intensity (not at all/a little/a lot) of the event evaluated. We chose to use this three-point model due to the children's age. There is evidence in the literature that three-point scales work better for the age group of interest (eight to 10 years) (Coombes et al., 2021).

2.5 Expert Panel

The preliminary instrument was submitted to a group of experts for consensus using the Delphi method. Ten researchers from were invited by e-mail to participate in the validation process, which occurred in three rounds at seven-day intervals. The number of rounds and the interval between rounds were defined based on the time constraint, to reduce the participant loss rate and because the literature points out that there are no significant changes of opinion in later rounds (Marques & Freitas, 2018).

In the first two rounds, the experts evaluated whether the items met the criteria of clarity, comprehensibility and suitability to the objective, freely expressing their suggestions and observations. These criteria were defined based on the literature (Marques & Freitas, 2018). The aim of the clarity criterion was to assess whether the wording of the item used a language that would not generate doubts in the children’s minds. The aim of the comprehension criterion was to assess whether what the item addressed could be easily understood by the children. The aim of the suitability criterion was to assess whether the item was adequate for achieving the proposed objective.

Consensus was considered reached when > 70% of the experts agreed that all items where clear, comprehensive and suitable. In each round, items for which the minimum consensus was not reached were either excluded or rewritten (McMillan et al., 2016). In the last round, the experts classified the items using a four-point scale (Marques & Freitas, 2018) considering comprehensibility (1- very difficult to understand; 2- difficult to understand; 3- easy to understand; 4- very easy to understand) and suitability to the objective (1- very inadequate; 2- inadequate; 3- adequate; 4- very adequate). Based on the scores of the experts, the content validity index of the items (CVI-I) was calculated considering the number of experts who attributed a score of 3 or 4 to the item divided by the total number of experts. After calculating the CVI-I for all items on the questionnaire, the CVI of the scale (CVI-S) was determined, which is the sum of the CVI-Is divided by the total number of items evaluated. Based on the literature, items with an index of ≥ 0.80 and scales with an index of ≥ 0.90 have satisfactory agreement (Polit & Beck, 2006). At the end of this phase, a questionnaire with 38 items was obtained.

2.6 Phase 2 – Pilot Study: Face Validation

The pilot study was conducted with 30 children eight to ten years of age recruited from the public schools and private school located in different neighborhoods of the city.

After the application of the questionnaire, the adequacy of the language and understanding of the items were analyzed (Willis & Artino, 2013). To determine acceptability and the need to include further items, the children were asked to give their opinions on the following: a) degree of difficulty in answering the questionnaire or item (easy or difficult); b) difficulty understanding the meaning of any word; c) desire to answer the questionnaire again; d) size of the instrument (large or small/whether it generated weariness); e) suggestions for the inclusion of other items considered important to the children. The children’s opinions were analyzed qualitatively. Items with deviations in interpretation or understanding were altered after a discussion and consensus among the researchers. Based on the children’s suggestions, an additional item was included, obtaining a questionnaire with 39 items.

2.7 Phase 3: Evaluation of Psychometric Properties

To evaluate the psychometric properties of the final questionnaire (39 items), the instrument was administered to a sample of 293 children eight to ten years of age recruited from only the public schools. The children involved in this phase did not participate in the previous steps.

Parents who authorized their children’s participation in the study answered by questionnaire addressing individual and sociodemographic characteristics (child’s sex and age, mother’s schooling and monthly household income). This questionnaire was sent to the homes of the children through the school administration office.

After the return of the sociodemographic questionnaires answered by the parents, the QoL questionnaire created in this study was administered to children collectively in the classroom or other space at the school, such as the library. As it was not possible to ensure the fluent reading of all children, the main researcher read each item and response option aloud. The time required to complete the questionnaire ranged from 15 to 25 min. The questionnaires were collected and attached to the socioeconomic questionnaire.

2.8 Statistical Analysis

Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Items with an item-total correlation < 0.30 and that indicated an increase in Cronbach’s alpha if the item were excluded were removed from the questionnaire (Field, 2009).

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) (Field, 2009) was performed to determine construct validity using the principal component method and Promax oblique rotation. This method was chosen because this was the first investigation on the dimensionality of items that measure QoL in a children’s environment and due to the lack of a hypothesis on the number of domains that should make up the instrument. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s sphericity test were performed to confirm whether the data were suitable for EFA (Field, 2009).

The first EFA was performed. Based on the combined analysis of Cronbach’s alpha and factor loadings, items that had primary factor loadings below the desired value (< 0.40) (Field, 2009) and/or would lead to an increase in Cronbach’s alpha if removed were excluded and new factor analyses were successively run until arriving at the final instrument. The final dimensional structure of the items was defined based on the Kaiser criteria (eigenvalue > 1) and the scree plot method (Field, 2009), supported by the theoretical reference. The factors were labelled considering the combination of meanings of all items that composed them.

The final instrument obtained through EFA was submitted to tests to measure test–retest reliability and discriminant validity. For such, the response scale of the questionnaire was scored in increasing order (0 = always/a lot; 1 = sometimes/a little; 2 = never/not at all), generating at total score for which higher scores denoted lower QoL in the environment. For negative items (e.g., “The streets in the neighborhood where I live have a lot of potholes”), the score was inverted (2 = always/a lot; 1 = sometimes/a little; 0 = never/not at all).

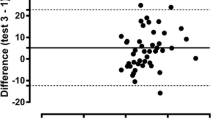

Test–retest reliability was measured using the weighted Kappa coefficient and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Weighted Kappa coefficients were used to compare scores obtained on each of the items at the initial administration to those obtained during the second administration after a period of seven days and were interpreted as proposed by Fleiss et al. (2003). ICCs were used to compare the totals of the scale and domains on the two different occasions and were interpreted as proposed by Koo and Li (2016).

Discriminant validity or contrast validity seeks to identify differences between groups in which such differences are theoretically expected (Echevarría-Guanilo et al., 2019). Discriminant validity was determined by comparing the total and domain scores of the scale between groups determined based on the individual and sociodemographic characteristics of the children. The hypothesis was that differences in the QoL of the children would be found according to sex (female and male), age (eight, nine and 10 years of age), mother’s schooling (≤ eight years of formal study or ≥ nine years of formal study), monthly household income dichotomized by the median (≤ R$ 2000 or > R$ 2000) (Brasil, 2020) and place of residence, which was determined based on the location of the child’s school (city center or district) (IBGE, 2020), since the students needed to select a school close to their residence when enrolling (Minas Gerais, 2018). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine the distribution of the quantitative variables associated with categorical variables. As nonparametric distribution was determined, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used.

All statistical tests were performed with the aid of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows, version 22.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

2.9 Ethical Considerations

This study received approval from the institutional review board of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (certificate number: 68497017.0.0000.5149) and was conducted in accordance with Resolution 466/2012 of the Brazilian Board of Health as well as the ethical principles contained in the Declaration of Helsinki. In all steps, the children were authorized to participate in the study by their parents or guardians, who signed a statement of informed consent. The children’s agreement to participate was obtained through an assent term. The experts involved in the validation step also agreed to participate by signing a statement of informed consent.

3 Results

3.1 Phase 1: Expert Panel

Eight experts participated in the study, composing a panel representative of the chosen fields. Six were from the healthcare field (medicine, dentistry and physical therapy), one was from the field of education and one was from the communications field. In the first round, 56 items were evaluated and the consensus among the experts was 82.1% (46 items). Among the 10 items that did not achieve agreement among the experts, six items were excluded and four were rewritten after the analysis of the suggestions. Moreover, one question was excluded because its construct was included in another question of the instrument and four other questions were reduced to two questions. At the end of this round, the instrument was composed of 47 items.

In the second round, consensus among the specialists was 85.1% (40 items). Among the seven items that did not achieve agreement among the experts, three items were excluded and four were reduced and merged into an existing item. Another three items were excluded after the analysis of the suggestions. The instrument was composed of 37 items at the end of this round.

Due to the dropout of one participant, seven experts evaluated the instrument in the last round. The CVI-I ranged from 0.71 to 1.0 and the CVI-S was 0.94. The two items that had a CVI-I of 0.71 were rewritten based on the suggestions of the experts. There was also the inclusion of an item addressing the school environment. The instrument was composed of 38 items at the end of this phase.

3.2 Phase 2 – Pilot Study: Face Validation

Among the 30 children who participated in the face validation phase, 16 (53.3%) were girls and 14 (46.7%) were boys with a mean age of 9.37 ± 1.03 years. The children spent an average of 11.9 min (maximum: 16′27″; minimum: 10′33″) answering the questionnaire.

The acceptability of the questionnaire was good, as no question was left blank and there were no reports of difficulty answering the questionnaire or understanding the words of the items. However, after a discussion with the children about each item, a need was found to perform changes to five items. Two items were not measuring what was proposed and the others required adjustments to the language. For example, the purpose of the item “I can walk to school” was to measure the distance between school and the child’s home. However, the children understood that this item was related to safety, mainly the lack of traffic safety and security in the neighborhood. To measure what was of interest (distance), the item was changed to “My house is far from school”. Other items were altered to make the language more appropriate and facilitate the understanding. For example, “full of water” was replaced with the term “flooded” based on the children’s suggestions. Few negative points were raised about the instrument. Three children (9.9%) found the questionnaire to be long and reported feeling tired when answering it.

The children suggested adding the item “I like living in my neighborhood”. The suggestion was heeded, as it is a generic item of considerable importance to understanding the extent of children’s satisfaction with the environment in which they live. At the end of this phase, an instrument with 39 items was obtained.

3.3 Phase 3: Evaluation of Psychometric Properties

A total of 261 children participated in this phase, 147 (56.3%) of whom were girls and 150 (57.5%) resided in the city center. The mean age of the children was 8.9 (SD = 0.814); 91 (34.9%) were eight years of age, 88 (33.7%) were nine and 82 (31.4%) were 10 years of age. One hundred ninety-seven (75.5%) of the mothers had ≥ nine years of schooling and average family income was U$ 606.51 (R$ 2541.29). The income of these families corresponds to less than three times the Brazilian monthly minimum wage, which is considered by the Brazilian government to be low income, qualifying these families for several governmental social programs (Brasil, 2007b).

The reliability analysis of the 39-item questionnaire (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.799) indicated that four items should be removed for having an item-total correlation < 0.30 and indicating an increase in Cronbach’s alpha if excluded.

The 35-item instrument was submitted to the first EFA. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin adequacy measure was 0.754, indicating that the data were sufficient for adequate factor analysis (Field, 2009). Bartlett’s sphericity test was χ2 = 2018.456 (SD: 595; p < 0.001), confirming that the dataset could be compacted by factor analysis (Field, 2009). Items with factor loadings below the desired level (< 0.40) and/or that would lead to an increase in Cronbach’s alpha if removed were excluded one by one and further factor analyses were performed until reaching an adequate structure of items. For the composition of the domain, the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalue > 1) suggested the extraction of eight factors, which was confirmed by the scree plot. The final definition of five domains was based on a dimensional structure of the items that found support in the theoretical model obtained in the qualitative study by Oliveira et al. (2020). Thus, the final version of the instrument had 27 items and five factors (Life satisfaction, Satisfaction with neighborhood amenities, Healthy environment, Social networks and Home protection). Table 1 displays the factor loadings of each item and the distribution of items by factor. The five factors explained 45.4% of the accumulated variance. The final version of the instrument was denominated Quality of Life in the Neighborhood Questionnaire for Children Eight to Ten Years of Age (QoL-N-Kids 8–10).

The QoL-N-Kids 8–10 instrument exhibited good internal consistency [Cronbach’s α = 0.805 (range: 0.792 – 0.804)] and the domains had values above or close to 0.70, which were considered satisfactory, demonstrating that the items measure the same construct (Cronbach, 1951; Field, 2009). Regarding the item-total correlations, the majority of coefficients were close to or above 0.30. The decision was made to maintain items with lower coefficients (< 0.30) because the exclusion of these items would not result in an increase in the total Cronbach alpha coefficient (Table 2).

Test–retest reliability was measured with 58% of the sample (n = 153). Considering the weighted Kappa coefficient, the temporal stability of the items ranged from 0.302 to 0.724. The majority of items (88.8%) had values indicative of satisfactory to good stability (0.40 to 0.75). Weak agreement was found for three items (“The streets in the neighborhood where I live are lighted”; “I live in a neighborhood that has good, clean air to breathe”; and “I talk with my friends”).

The score on the total QoL-N-Kids 8–10 ranged from 0 to 45 points, with a mean of 13.1 (SD = 6.2) and median of 13. Based on the ICC, the reliability of the total scale was considered excellent (0.917) and all domains exhibited good reliability (0.80 to 0.91) (Table 3).

In the analysis of discriminant validity (QoL-N-Kids 8–10 scores according to sociodemographic variables), the girls had lower QoL scores related to the environment, with significant differences regarding the total score (p = 0.009) as well as the Satisfaction with neighborhood amenities (p = 0.04) and home protection (p = 0.003) domains. The eight and nine-year-old children had lower scores on the healthy environment domain (p = 0.008) compared to those ten years of age. Children from families with a higher monthly income (> R$ 2000) had a lower score on the life satisfaction domain (p = 0.20) and higher score on the home protection domain (p = 0.04). Children who resided in the district of the city had a lower score on the satisfaction with neighborhood amenities (p = 0.005) and a tendency toward a significantly lower total score (p = 0.058) (Table 4).

4 Discussion

This is an innovative study in which a tool was developed to assess neighborhood QoL from the perspective of children. To create the QoL-N-Kids 8–10 questionnaire, we sought to implement a systematic process (Artino et al., 2014) that ensured the development of a valid, reliable tool of quality. Despite the costly process, which requires more time, skill and different resources in each phase (Artino et al., 2014), the questionnaire was developed with care, ensuring the right of participation to the child population (Brasil, 1990).

Content validity was sought through two different steps (Polit & Beck, 2006; Rajmil et al., 2012). First, in a previous moment (see Oliveira et al., 2020), a qualitative study was conducted to ensure the subjectivity of the construct and enable the development of a conceptual model that encompasses all features of the environment that are important to the QoL of the child population studied (Oliveira et al., 2020). Next, the relevance of the content of the items was evaluated by an expert panel, who certified the content validity of the items and the scale as a whole (Polit & Beck, 2006).

The factorial framework of the QoL of the environment for children extracted in this study consisted of five domains: Life satisfaction, Satisfaction with neighborhood amenities, healthy environment, Social networks and Home protection. This framework illustrates the importance of promoting the rights stipulated in the Children’s Rights Convention (Brasil, 1990), especially rights of provision, which recognize the social rights of children related to health, education, social security, physical care, family life, recreation and culture (Andrade, 2010; Brasil, 1990). It also underscores some important aspects related to achieving community wellbeing, such as liking where one lives, feeling safe and having loving, supportive relationships (Cloutier et al., 2019). Moreover, the QoL-N-Kids 8–10 questionnaire resembles some domains the C-QOL (Jirojanakul & Skevington, 2000) and MSLSS (Huebner, 1994), both of which have been validated for use in Brazil (Barros et al., 2014; Pinto, 2018).

The weak agreement found for three items may have been influenced by different factors, such as the interval of days until the retest, the form of application and the age of the participants (Fleiss et al., 2003). The questionnaire was administered a second time after a seven-day interval. Although this is a commonly used period in studies (Farias Júnior et al., 2017), the content of some items may have exerted an influence on reproducibility. For example, the item “The streets in the neighborhood where I live are lighted” refers to a feature that can vary from one week to the next, as the simple fact of a single burnt-out streetlight makes the street darker and could influence the perception of a child.

The QoL-N-Kids 8–10 questionnaire was capable of discriminating differences in the children’s answers according to age in years, sex, monthly household income and place of residence. The findings related to age are consistent with data reported in previous studies that found a worse wellbeing with the increase in age (Casas & González-Carrasco, 2019; González-Carrasco et al., 2019). Casas & González-Carrasco (2019) support the hypothesis that the tendency toward a reduction in wellbeing begins at around 10 years of age. According to the authors, this change appears to be a normal developmental phenomenon, which may start at around 10 years of age depending on the micro- and macro-environment.

In the present study, girls had lower scores compared to boys, indicating better QoL in relation to their living environment. There is no consensus in the literature on the association between gender and wellbeing (Lima & Araujo de Morais, 2018). Some studies report differences (Kaye-Tzadok et al., 2017), whereas other have found no differences (Lawler et al., 2017; González-Carrasco et al., 2019). Although the sample in the present study was not representative, the difference, especially with regards to the structure of the neighborhood, indicates that the QoL-N-Kids 8–10 questionnaire could contribute to studies that seek to analyze the perception of the living environment as a function of gender, making further contributions to the subject.

The findings related to income are also supported by the scientific literature, as a poorer socioeconomic status is a predictor of worse QoL (Rueden et al., 2006), exerts a negative impact on family relations (Komro et al., 2011) and constitutes an obstacle in terms of fulfilling basic needs (Stephens, 2012). In the present study, however, children from low-income families had lower scores for the “Home protection” domain. If we consider the stereotypes and beliefs that adults have regarding the life and wellbeing of children (Casas et al., 2013), this would not be an expected result. However, Casas et al. (2013) state that much information is simply never asked directly of children and adolescents and, therefore, reflects the opinions of adults who “suppose that they know” about a child’s life. As the sample of the present study was not representative of the population studied, it is necessary to determine whether such results would be repeated in a representative sample (Casas et al. 2013). Therefore, this difference should be explored in greater detail in future research.

Regarding place of residence, it is common to find differences when neighborhoods have opposing characteristics (Hassine et al., 2014), which explains the present results, as the regions analyzed have different structural features. The district of the city has a greater density of buildings, commercial establishments and services. This is a region in constant movement, with the circulation of people and cars and evident progress of the urban space. The center of the city is a historical neighborhood, where some of the large houses have an incipient commerce, with businesses the provide services and public services serving City Hall. This region has low circulation of people and cars, especially on weekends (Bretas, 2017). Although the QoL-N-Kids 8–10 scores were not compared according to specific characteristics of the geographic regions (e.g., pollution, basic sanitation, types of residence, crime level, etc.), it is evident that the instrument was capable of identifying structural differences between the two organizational spaces of the city.

This first study with the QoL-N-Kids 8–10 questionnaire indicates that the tool is capable of measuring neighborhood QoL and has satisfactory psychometric properties. Therefore, although the concept of QoL can vary among different places and societies (Serag El Din et al., 2013), it is possible for this tool to be used in other countries following cross-cultural adaptation and validation, as the perceptions of the children in this study regarding the features of their neighborhood are similar to the views of children in other nations (Carroll et al., 2015; Derr & Tarantini, 2016; Ergler et al., 2015; Malone, 2013). As found in the present investigation, children and adolescents in New Zealand (Carroll et al., 2015; Ergler et al., 2015), Australia (Ergler et al., 2015; Malone, 2013) and the United States (Derr & Tarantini, 2016) want to live in cities that have safe environments, public recreational spaces and opportunities to live with their families and friends.

Further studies should be conducted to evaluate other psychometric properties. Criterion validity was not evaluated in the present study, as this step requires a reference standard for comparison to the tool that is being created (Rajmil et al., 2012). Despite the broad diversity of assessment tools published in the literature (Rajmil et al., 2012; Solans et al., 2008), the absence of a “gold-standard” measure for QoL hinders this investigation (Seidl & Zannon, 2004). Moreover, the focus of the present study was neighborhood QoL and assessment tools addressing this aspect are rare (Huebner, 1994; Jirojanakul & Skevington, 2000). A large part of the QoL assessment tools for children used in Brazil are directed at health, were developed in the United States and Europe, and do not address issues of the environment (Rajmil et al., 2012; Solans et al., 2008).

4.1 Limitations

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. Although the population of the study has characteristics similar to those found in a large part of the Brazilian urban population, Brazil is a country with considerable cultural diversity and the specific traits of each region can exert an influence on the understanding of the items (Souza et al., 2014). Therefore, future studies should investigate whether the psychometric properties are maintained with children from other states. Moreover, the sample was concentrated in the urban region of a medium-sized city (202,942 residents) (IBGE, 2019) and, therefore, does not represent the perceptions of Brazilian children who reside in rural areas.

Despite the attempt to maintain the proportionality of the children enrolled at public and private schools in all phases of the study, it was not possible to include children from the private school in the last step. Data collection was interrupted due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Santa Luzia, 2020). As a sample larger than the minimum estimated for the statistical analyses had already been reached (Anthoine, et al., 2014) the decision was made to proceed with the study. However, it is strongly recommended that further studies be carried out including the population of children from private schools.

QoL-N-Kids 8–10 is a starting point for understanding the perceptions of children regarding their living environment, especially the neighborhood. Therefore, other questionnaires should be used together with this instrument for the assessment of other QoL domains, enabling more in-depth knowledge on the perceptions of children in terms of their school and family environments.

4.2 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study resulted in the creation of the QoL-N-Kids 8–10 questionnaire, a measure developed in Brazilian Portuguese with adequate psychometric properties to measure neighborhood QoL in children eight to ten years of age. This assessment tool will be useful for researchers and individuals who work with city planning and the formulation of public policies. Further studies should be conducted to measure criterion validity and determine discriminant validity in distinct socioeconomic contexts.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Andrade, L.B.P. (2010) Educação infantil: discurso, legislação e práticas institucionais [online]. São Paulo: Editora UNESP; Cultura Acadêmica (p 193). Available from SciELO Books. http://books.scielo.org

Anthoine, E., Moret, L., Regnault, A., Sébille, V., & Hardouin, J. B. (2014). Sample size used to validate a scale: A review of publications on newly-developed patient reported outcomes measures. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-014-0176-2

Artino, A.R., La Rochelle, J.S., Dezee, K.J., Gehlbach, H. (2014). Developing questionnaires for educational research: AMEE Guide No. 87. Medical Teacher, 36(6), 463–474. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.889814

Barros, L. P. de, Petribú, K., Sougey, E., Huebner, E. S. (2014). Multidimensional Students' Life Satisfaction Scale: translation into Brazilian Portuguese and cross-cultural adaptation. Rev Bras Psiquiatr, 36(1),102–3. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1146

Bedin, L. M., & Sarriera, J. C. (2014). Propriedades psicométricas das escalas de bem-estar: PWI, SWLS, BMSLSS e CAS. Avaliação Psicológica, 13(2), 213–225.

Brasil. (1990). Decreto nº 99.710, de 21 de novembro de 1990. Promulga a Convenção sobre os Direitos da Criança. Retrieved Jun 9, 2020, from http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/1990-1994/d99710.htm

Brasil. (1996). Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Retrieved Jun 9, 2020, from http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9394.htm

Brasil. (2007b). Decreto nº 6.135, de 26 de junho de 2007b. Dispõe sobre o Cadastro Único para Programas Sociais do Governo Federal e dá outras providências. Retrieved Jun 9, 2020, from http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007b-2010/2007b/decreto/d6135.htm

Brasil. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). (2020) Pesquisa Nacional de Amostra por Domicílios. Retrieved Jun 9, 2020, from https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/periodicos/59/pnad_2013_v33_br.pdf

Brasil. Ministério da Educação. (2014) Nota técnica. Indicador de Nível Socioeconômico das Escolas de Educação Básica (ESSI) participantes da Avaliação Nacional da Alfabetização (ANA). Retrieved Jun 9, 2020, from http://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_basica/saeb/ana/resultados/2014/nota_tecnica_ESSI.pdf

Brasil. (2007a). Decreto nº 6.094, de 24 de abril de 2007a. Dispõe sobre a implementação do Plano de Metas Compromisso Todos pela Educação, pela União Federal, em regime de colaboração com Municípios, Distrito Federal e Estados, e a participação das famílias e da comunidade, mediante programas e ações de assistência técnica e financeira, visando a mobilização social pela melhoria da qualidade da educação básica. Retrieved Jun 9, 2020, from http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2007a-2010/2007a/Decreto/D6094.htm

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). (2019). Conheça cidades e Estados do Brasil. Retrieved Jun 9, 2020, from https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/mg/santa-luzia/panorama

Bretas, P. F. F. (2017). Do Ouro ao Pó: A (Re)produção do Espaço Urbano em Santa Luzia (MG). Revista Interdisciplinar De Gestão Social, 6(1). Retrieved Jun 9, 2020, from https://periodicos.ufba.br/index.php/rigs/article/view/16950

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (Vol. 1, pp. 993–1027). John Wiley & Sons.

Carrillo, G., Alfaro, J., Aspillaga, C., et al. (2021). Well-Being from the Understanding of Children and Adolescents: A Qualitative Metasynthesis. Child Indicators Research, 14, 1677–1701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09816-1

Carroll, P., Witten, K., Kearns, R., & Donovan, P. (2015). Kids in the City: Children’s Use and Experiences of Urban Neighbourhoods in Auckland, New Zealand. Journal of Urban Design., 20(4), 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2015.1044504

Casas, F., & González-Carrasco, M. (2019). Subjective Well-Being Decreasing With Age: New Research on Children Over 8. Child Development., 90(2), 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13133

Casas, F., Bello, A., González, M., et al. (2013). Children’s Subjective Well-Being Measured Using a Composite Index: What Impacts Spanish First-Year Secondary Education Students’ Subjective Well-Being? Child Indicators Research, 6, 433–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-013-9182-x

Casas F. (2016) Children, Adolescents and Quality of Life: The Social Sciences Perspective Over Two Decades. In: Maggino F. (eds) A Life Devoted to Quality of Life. Social Indicators Research Series, 60. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20568-7_1

Cloutier, S., Ehlenz, M.M., Afinowich, R. (2019). Cultivating Community Wellbeing: Guiding Principles for Research and Practice. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 2(8), 277–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42413-019-00033-x

Coombes, L., Bristowe, K., Ellis-Smith, C., et al. (2021). Enhancing validity, reliability and participation in self-reported health outcome measurement for children and young people: A systematic review of recall period, response scale format, and administration modality. Quality of Life Research, 30, 1803–1832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02814-4

Creswell, J. W. (2010) Projeto de pesquisa: métodos qualitativo, quantitativo e misto. 3ª ed. Porto Alegre (RS): Artmed. 248p.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

de Abreu, D. P., et al. (2016). Estressores psicossociais, senso de comunidade e bem-estar subjetivo em crianças e adolescentes de zonas urbanas e rurais do Nordeste do Brasil. Cadernos De Saúde Pública, 32(9), e00126815. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00126815%3e

Derr, V., & Tarantini, E. (2016). “Because we are all people”: Outcomes and reflections from young people’s participation in the planning and design of child-friendly public spaces. Local Environment, 21(12), 1534–1556. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2016.1145643

Echevarría-Guanilo, M. E., Gonçalves, N. e Romanoski, P.J. (2019). Psychometric properties of measurement instruments: conceptual basis and evaluation methods - part II. Texto & Contexto – Enfermagem, 28(e20170311). https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-265X-tce-2017-0311

Ergler, C., Smith, K., Kotsanas, C., & Hutchinson, C. (2015). What Makes a Good City in Pre-schoolers’ Eyes? Findings from Participatory Planning Projects in Australia and New Zealand. Journal of Urban Design, 20(4), 461–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2015.1045842

FariasJúnior, J. C., Loch, M. R., Lima Neto, A. J., Sales, J. M., & Ferreira, F. E. L. L. (2017). Reprodutibilidade, consistência interna e validade de construto do KIDSCREEN-27 em adolescentes brasileiros. Cadernos De Saúde Pública, 33(9), e00131116. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00131116

Ferreira Lima, R. F., & Araujo de Morais, N. (2018). Subjective well-being of children and adolescents: Integrative review. Ciencias Psicológicas, 12(2), 249–260. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v12i2.1689

Field, A. (2009). Descobrindo a estatística usando o SPSS. Artmed.

Fleiss, J. L., Levin, B., & Paik, M. C. (2003). Statistical methods for rates and proportions. John Wiley & Sons.

Gómez D. O., Casas F., Inzunza J. A., Costa P. A. (2017). School and Neighborhood: Influences of Subjective Well-Being in Chilean Children. In: Sarriera J., Bedin L. (eds) Psychosocial Well-being of Children and Adolescents in Latin America. Children’s Well-Being: Indicators and Research, vol 16. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55601-7_8

González-Carrasco, M., Casas, F., Viñas, F., Malo, S., & Crous, G. (2019). The interplay between school and home location and its relationship with children’s subjective well-being. Children’s Geographies, 17(6), 676–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2019.1635993

Hassine, K., Markouyeux, A., Annabi-Attia, T., & Fleury-Bahi, G. (2014). Measuring Quality of Life in the Neighborhood: The Cases of Air-Polluted Cities in Tunisia. Social Indicators Research, 119(3), 1603–1612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0565-7

Huebner, E. S. Preliminary Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Life Satisfaction Scale for Children. (1994). Psychological Assessment, 6(2),149–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.149

Jirojanakul, P., & Skevington, S. (2000). Developing a quality of life measure for children aged 5–8 years. The British Journal of Health Psychology, 5(3), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910700168937

Kaye-Tzadok, A., Kim S. S., Main G. (2017). Children's subjective well-being in relation to gender — What can we learn from dissatisfied children? Children and Youth Services Review, 80, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.058.

Komro, K. A., Flay, B. R., Biglan, A., Promise Neighborhoods Research C. (2011). Creating nurturing environments: a science-based framework for promoting child health and development within high-poverty neighborhoods. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(2),111-34.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0095-2

Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

Lawler, M. J., Newland, L. A., Giger, J. T., et al. (2017). Ecological, Relationship-Based Model of Children’s Subjective Well-Being: Perspectives of 10-Year-Old Children in the United States and 10 Other Countries. Child Indicators Research, 10, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-016-9376-0

Lima, F. F. R., & Araujo de Morais, N. (2018). Bienestar Subjetivo de Niños/as y Adolescentes: revisión integradora. Ciencias Psicológicas, 12(2), 249–260. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v12i2.1689

Santa Luzia. (2020). Decreto nº 3541, de 18 de março de 2020. Dispõe sobre medidas temporárias de prevenção ao contágio e de enfrentamento e contingenciamento, no âmbito do Poder Executivo, da epidemia de doença infecciosa viral respiratória causada pelo agente Coronavírus - COVID-19. Retrieved Jun 9, 2020, from https://leismunicipais.com.br/a1/mg/s/santa-luzia/decreto/2020/354/3541/decreto-n-3541-2020-dispoe-sobre-medidas-temporarias-de-prevencao-ao-contagio-e-de-enfrentamento-e-contingenciamento-no-ambito-do-poder-executivo-da-epidemia-de-doenca-infecciosa-viral-respiratoria-causada-pelo-agente-coronavirus-covid-19?r=p

Malone, K. (2013). “The future lies in our hands”: children as researchers and environmental change agents in designing a child-friendly neighbourhood. Local Environment, 18(Issue 3), 372–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.719020

Marques, J. B. V., & de Freitas, D. (2018). Método DELPHI: Caracterização e potencialidades na pesquisa em Educação1 1 Apoio: Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP). Pro-Posições, 29(2), 389–415. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-6248-2015-0140

McMillan, S. S., King, M., & Tully, M. P. (2016). How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 38(3), 655–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0257-x

Minas Gerais. (2018). Resolução SEE nº 3765/2018. Estabelece normas para a realização, em 2018, do Cadastro Escolar para o Ensino Fundamental e da matrícula nas redes públicas de ensino em Minas Gerais. Retrieved Jun 9, 2020, from https://www2.educacao.mg.gov.br/images/documentos/3765-18-r.pdf.

Moreno Sancho, F., Tsakos, G., Brealey, D., Boniface, D., & Needleman, I. (2020). Development of a tool to assess oral health-related quality of life in patients hospitalised in critical care. Quality of Life Research, 29(2), 559–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02335-1

Oliveira, C. A. S., Vargas, A. M. D., Ferreira, F. M., & Ferreira, E. F. (2020). Brazilian Children’s Understanding of the Quality of Life in Their Living Environment: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 5101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145101

Pinto, G. M. C. (2018). Propriedades psicométricas do instrumento WHOQoL children para avaliação da qualidade de vida em crianças. Dissertação (Mestrado)- Programa de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia de Produção, Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná. Ponta Grossa. 120 f. Retrieved Jun 9, 2020, from http://repositorio.utfpr.edu.br/jspui/handle/1/3073

Poletto, M., & Koller, S. H. (2008). Contextos ecológicos: Promotores de resiliência, fatores de risco e de proteção. Estudos De Psicologia., 25(3), 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-166X2008000300009

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2006). The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and Recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 29(5), 489–497. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20147

Rajmil, L., Roizen, M., Psy, A. U., Hidalgo-Rasmussen, C., Fernandez, G., Dapueto, J. J., et al. (2012). Health-related quality of life measurement in children and adolescents in Ibero-American countries, 2000 to 2010. Value Health., 15(2), 312–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.028

Rueden, U., Gosch, A., Rajmil, L., Bisegger, C., & Ravens-Sieberer, U. (2006). Socioeconomic determinants of health related quality of life in childhood and adolescence: Results from a European study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(2), 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.039792

Seidl, E. M. F., & Zannon, C. M. L. C. (2004). Qualidade de vida e saúde: Aspectos conceituais e metodológicos. Cadernos De Saúde Pública, 20(2), 580–588. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2004000200027

Serag El Din, H., Shalaby, A., Farouh, H. E., & Elariane, S. A. (2013). Principles of urban quality of life for a neighborhood. HBRC Journal., 9(1), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hbrcj.2013.02.007

Solans, M., Pane, S., Estrada, M. D., Serra-Sutton, V., Berra, S., Herdman, M., et al. (2008). Health-related quality of life measurement in children and adolescents: A systematic review of generic and disease-specific instruments. Value Health., 11(4), 742–764. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00293.x

Souza, J. G. S., Pamponet, M. A., Souza, T. C. S., Pereira, A. R., Souza, A. G. S., & Martins, A. M. E. B. L. (2014). Tools used for evaluation of Brazilian children’s quality of life. Revista Paulista de Pediatria, 32(2), 272–278. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-0582201432214313

Stephens, C. (2012). Urban inequities; urban rights: A conceptual analysis and review of impacts on children, and policies to address them. Journal of Urban Health, 89(3), 464–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-011-9655-5

UNICEF. (2022). Programa Cidades Amigas das Crianças. https://www.unicef.pt/o-que-fazemos/o-nosso-trabalho-em-portugal/programacidades-amigas-das-criancas/. Accessed 2022.

Wallander, J. L., & Koot, H. M. (2016). Quality of life in children: A critical examination of concepts, approaches, issues, and future directions. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.007

Wallander, J. L., Schmitt, M., & Koot, H. M. (2001). Quality of life measurement in children and adolescents: Issues, instruments, and applications. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(4), 571–585. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.1029

Willis, G. B., & Artino, A. R., Jr. (2013). What Do Our Respondents Think We’re Asking? Using Cognitive Interviewing to Improve Medical Education Surveys. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 5(3), 353–356. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-13-00154.1

World Health Organization. (1995). The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science and Medicine, 41(10), 1403–1409. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k

World Health Organization. (1998). The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Social Science and Medicine, 46(12), 1569–1585. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00009-4

Funding

Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Camilla Aparecida Silva de Oliveira participated in the conception of the project, data analysis and interpretation and writing of the paper. Ramon Targino Firmino participated in the data analysis and interpretation and writing of the paper. Fernanda de Morais Ferreira, Andréa Maria Duarte Vargas and Efigênia Ferreira e Ferreira participated in the conception of the project, data analysis and interpretation and writing of the paper. All authors approved the final version of the paper to be published and take responsibility for all aspects of the study, assuring the precision and integrity of all parts of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study received approval from the institutional review board of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (certificate number: 68497017.0.0000.5149).

Consent to Participate

The children were authorized to participate in the study by the parents or guardians, who signed an informed consent statement. The experts involved in the validation step also agreed to participate by signing an informed consent statement.

Consent for Publication

All authors agree with the publication of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Oliveira, C.A.S., Firmino, R.T., de Morais Ferreira, F. et al. Development and Validation of the Quality of Life in the Neighborhood Questionnaire for Children 8 to 10 Years of Age (QoL-N-Kids 8–10). Child Ind Res 15, 1847–1870 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09944-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09944-2