Abstract

Subjective well-being is important for young children to be successful and happy now and in the future. Studies on the subjective well-being of young children are relatively few. Subjective well-being includes different factors such as family, school, friends, positive life experiences. Different from other age groups, subjective well-being factors differ in younger age groups (3–6 years). This study aims to develop a subjective well-being scale in line with what young children care about. The subjective well-being scale in this study consists of three dimensions: Positive Relationships with Others, Life Standard, and Life Satisfaction. The subjective well-being scale for young children is a semi-structured, self-reported, and designed for all daily living environments, regardless of a single environment. Subjective well-being scale shows good psychometric properties. By discussing the dimensions, the factors that are important in the subjective well-being of young children are revealed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Subjective well-being is a multidimensional concept that includes different elements such as physical (Hinkley et al., 2014; Kennedy-Behr et al., 2015), social (Kennedy-Behr et al., 2015), affective and cognitive (Fiorelli, 2011). The fact that the concept has an abstract and culture-specific structure makes it more complex (Sandseter & Seland, 2016, 2018).

It is seen that subjective well-being studies are mostly conducted with children aged 8 and over. In studies on the subjective well-being of children; measurements were made in the areas of family and home life, friendship, money and possessions, school life, local space, time use, personal well-being, children’s rights, health, self-perceptions and general happiness (Andresen et al., 2019; Lam & Comay, 2020). Recently, the effect of technology on subjective well-being has been investigated due to its entertaining feature (Abbasi et al., 2021; Przybylski & Weinstein, 2019; Twenge & Campbell, 2018). Using these dimensions, attempts have been made to reveal the children’s subjective well-being, but could not achieve the desired results (Davidson, 2005). This situation emphasizes that the concept of subjective well-being may be specific to developmental periods. Here, the cognitive element comes into play (Fiorelli, 2011), “What is important for the individual?” question comes to the fore. It is more correct to look at this question from the point of view of developmental periods. This paper illustrates efforts to measure subjective well-being in terms of what young children care about.

1 Literature Review

Subjective well-being means that children are healthy and happy. Children who are healthy and happy become individuals who are successful in their school and personal lives and have a positive outlook on the future (Huppert & So, 2013; Mayr & Ulich, 2009). In addition, the low level of factors affecting subjective well-being in early childhood affects subjective well-being in adulthood - not in childhood and adolescence (Coffey et al., 2015; Nikolova & Nikolaev, 2021; Rees, 2019). When the literature is examined, it is seen that studies measuring the subjective well-being of young children are limited. Parental scales are often used because young children are not mature enough in terms of cognitive, affective, language and communication, have difficulties in participation, and power imbalances in adult-child relationships. Parents are preferred because they are considered as people who know their children best (Andresen et al., 2019; Lam & Comay, 2020). However, in studies where parents were compared with their children’s reports; it was found that parents tend to score higher than their children (Davidson, 2005; Vieira et al., 2018). Teacher reports were closer to children’s reports (Davidson, 2005). This shows that parents cannot be objective in scoring their children.

In the literature, two scales based on parental reports have been found to measure the subjective well-being of young children: The Revised Children Quality of Life Questionnaire (KINDLR) (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2007) and The Parent Version of the 10-Item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children (PANAS-C-P) (Ebesutani et al., 2012). The scales based on the teacher report are The Leuven Well-being and Involvement Scales (Leavers, 2005) and Positive Development and Resilience in Kindergarten (PERIK) (Mayr & Ulich, 2009).

Subjective well-being is a subjective concept. Self-assessment of the child will give the best results. When studies based on the child’s self-report were investigated, a limited number of studies were found. Some of the self-report studies were open-ended and some were structured interviews.

Koch (2018) asked 16 children aged 5 to take pictures of what makes them happy at school. In the photographs they took, the children narrated happiness as playing with other children. Toys, playground equipment such as swings and slides, aesthetic nature and pattern photographs were also taken by children. Children also told stories of excitement and risky play (physical and psychological) and humorous stories against rules. Lam and Comay (2020) used a story completion task that asked 25 children aged 4–6 to describe the good or bad things at school for the characters in the story. Children in the study frequently expressed play, social interaction, routine, and care-lack of care (such as suffering, kindness, sharing, being rude). Permiakova et al. (2016) asked 86 children aged 5–6 open-ended questions about happiness. In the study, children associated happiness with positive emotional experiences, family, material things, personal achievements, relationships with people, vacations, and dreams.

As a research in which the structured interview method was used, only Sandseter and Seland’s (2016, 2018) study was found in the literature. They used an electronic questionnaire on children’s life at school. In conclusion, physical environment, toys/equipment, routine activities, daily life and participation experiences in decision making, relationships with staff and other children were found to be effective in the well-being of young children.

In some studies (Shoshani & Slone, 2017), scales developed for older children were adapted to younger children: The Shortened Positive and Negative Affect Scale for Children (PANAS-C) (Ebesutani et al., 2012), Brief Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS) (Seligson et al., 2003) etc.

Studies have shown that young children can express themselves and say what they like and dislike in their lives (Koch, 2018; Lam & Comay, 2020; Permiakova et al., 2016; Sandseter & Seland, 2016, 2018). However, the majority of these studies aimed to measure subjective well-being at school. The concept of subjective well-being includes subjects such as family and home life, friendship, money and possessions, children’s rights, health, self-perceptions as well as school life (Andresen et al., 2019; Lam & Comay, 2020). For this reason, the subjective well-being of young children should not be limited to school life only. This study aims to develop a self-report scale of general well-being in line with what young children care about.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

Children were attending pre-school institutions in a province in southwestern Turkey. The ages of the children were between 3 and 6 years; 3 years 63 (18.4%), 4 years 82 (23.9%), 5 years 113 (32.9%), 6 years 85 (24.8%). One hundred sixty five (48.1%) of the children were girls. The education levels of the children’s parents were mostly high school and graduate; for mother, high school 133 (38.8%), graduate 178 (51.9%), for father, high school 132 (38.5%), graduate 188 (54.8%). Family income levels were mostly middle and high; respectively 168 (48.9%), 125 (36.5%). Children’s preschool attendance was mostly one or two years; one year 158 (46.1%), two years 141 (41.1%), three or more years 44 (12.8%). In the study, a total of 22 children were excluded because they did not want to participate in the study and were thought to not understand the questions. See Table 1.

2.2 Instruments

Positive Development and Resilience in Kindergarten (PERIK; Mayr & Ulich, 2009)

The PERIK is a teacher-evaluation scale that measures the social-emotional well-being of young children. It was developed for observing children in early childhood settings in six dimensions: Making contact/social performance, self control/thoughtfulness, self-assertiveness, emotional stability/coping with stress, task orientation, pleasure in exploring. Original PERIK was reported highly reliable (Mayr & Ulich, 2009). The PERIK was adapted into Turkish by Saltalı et al. (2018). In PERIK, which consists of six dimensions and 30 items, a five-point rating scale is used. Items are scored as never, rarely, sometimes, mostly, always. The Cronbach Alpha coefficient of PERIK was calculated between .74 and 92 (Saltalı et al., 2018). In the present study, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was .85 for the overall scale.

2.3 Scale Development

Firstly, the researcher conducted a literature review. Scales used for younger and older children, and articles on this subject were searched. Cummins and Lau’s (2005), Personal Well-being Index-School Children, Huebner’s (1991) Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale, Ryff’s (1989) Psychological Well-being Scale, Mayr and Ulich’s (2009) PERIK were examined by the researcher (Table 2).

Expert opinion was obtained from two academicians for the scale. One of these academicians was an expert in the field of subjective well-being and the other was an expert in the field of preschool education. It was important for the development of the scale that one of these experts was working in the field of subjective well-being and the other was getting to know young children. The scale was created in line with the opinions of these experts.

The first trial of the scale was done with 132 children. These results were analyzed and items with factor loadings of .30 and below were removed. Items that were inconsistent in the factor structure and that were under two or more factors were excluded, starting with those that were less necessary for the scale. The scale was rearranged. The scale, consisting of 3 dimensions and 22 items, was then administered to 343 children. The item number of the scale was positive for the scale due to the limited attention span of young children. The scale is a three-point rating scale and the ratings are visualized in a way that children can understand (large circle for a lot, medium circle for a little, small circle for nothing). In the study, the children were taken to a quiet room and data were collected by the researcher through individual interviews. The items of the scale were read by the researcher and the children marked them with a pencil.

3 Results

3.1 Reliability Study

For the reliability of the SWB-YC, Cronbach Alpha coefficient (α), means and standard deviations of each item, item total correlations, Composite Reliability (CR) and test-retest were conducted.

The SWB-YC consists of three dimensions: Positive Relationships with Others (8 items), Life Standard (7 items), and Life Satisfaction (7 items). The Cronbach alpha was .71 for the overall scale, .64 for Positive Relationships with Others, .67 for Life Standart, .67 for Life Satisfaction. Item-total correlations were positive, all items were above .25 except for one item. CR was above .70. See Table 3.

23 children aged 5 were retested at 20-day intervals. As a result of the retest, statistically significant relationships were found between the three dimensions of the SWB-YC (r = .63 for the overall scale, r = .36 for the Positive Relationships with Others, r = .71 for the Life Standard, r = .42 for the Life Satisfaction).

3.2 Validity Study

Construct validity was conducted for the validity of the SWB-YC. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), convergent and discriminant validity and concurrent validity were used as construct validity.

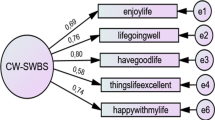

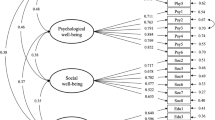

The fit statistics calculated by CFA performed to confirm the three-factor structure of the SWB-YC were as follows: X2/sd = 2.63, AGFI = .85, GFI = .87 and RMSEA = .06. According to the results of CFA, it is possible to assert that the SWB-YC is a valid model with an acceptable fit. See Fig. 1.

For convergent validity, t-values and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were calculated. Accordingly, t-values were significant and AVE coefficients for all sub-dimensions were below .50. CR and α were higher than AVE. See Table 4.

For discriminant validity, the correlations between sub-dimensions, Maximum Shared Variance (MSV) and Average Shared Variance (ASV) were calculated. There were significant relationships between the sub-dimensions of the SWB-YC (Positive Relationships with Others and Life Satisfaction r = .24, p < .01; Positive Relationships with Others and Life Standard r = .17, p < .01; Life Standard and Life Satisfaction r = .11, p < .05) (See Table 2). MSV = 0.14, ASV = 0.10 for the Positive Relationships with Others, MSV = 0.06, ASV = 0.05 for the Life Standard, MSV = 0.14, ASV = 0.08 for the Life Satisfaction. In line with these findings, MSV < AVE and ASV < MSV could be said for the SWB-YC. In addition, the square roots of AVE were higher than the correlations between factors. See Table 4.

For concurrent validity, the correlations between the SWB-YC and the PERIK were examined. Statistically significant relationships were found between the PERIK Self-assertiveness and the SWB-YC Life Standard (r = .33, p < .05). No statistically significant relationships were found between other sub-dimensions (p > .05). See Table 5.

The effects of age and gender on the three dimensions of the SWB-YC were examined. The analyzes revealed that the SWB-YC scores increased with age (χ2 = 40.66, p < .05, See Table 6). In terms of gender, girls scored higher on Positive Relationships with Others and Life Satisfaction than boys; girls and boys did not differ significantly on Life Standard. In addition, the three dimensions of the SWB-YC were found not to differ statistically in terms of parent education levels, family income levels, and preschool attendance (p > .05).

4 Discussion

Subjective well-being scales based on young children’s self-report are relatively few. Existing structured scales are also related to the young child’s perception of a certain environment (Sandseter & Seland, 2016, 2018). The SWB-YC is a semi-structured interview scale as preschool children differ in their reading abilities. The current study identified three dimensions in the subjective well-being of young children: “Positive Relationships with Others”, “Life Standard” and “Life Satisfaction”.

The dimensions found in this study were consistent with studies on the factors that determine the subjective well-being of young children. Relationships with people were important in the subjective well-being of young children (Koch, 2018; Lam & Comay, 2020; Permiakova et al., 2016; Sandseter & Seland, 2018). The age of 3–6 is a period in which the child moves from the family environment to the school environment. Establishing positive relationships with friends, teachers and staff working in the institution and participating in the decision-making processes are a situation that children want (Sandseter & Seland, 2018). Children also expressed positive emotional experiences such as helping, sharing, and kindness (Lam & Comay, 2020; Permiakova et al., 2016; Sandseter & Seland, 2018). In this study, the Positive Relationships with Others includes relationships with family, friends, teachers, staff, experiences of participation in decisions, and experiences of positive relationships between people.

Another important thing for young children is life standard. The economic situation of the family affects the subjective well-being of the child (Nikolova & Nikolaev, 2021). The physical environment, toys, garden play equipment such as swings, slides, material things, gifts, holidays, birthdays are things that children enjoy (Koch, 2018; Permiakova et al., 2016; Sandseter & Seland, 2016; Storli & Sandseter, 2019). In this study, the Life Standart is about home and school opportunities offered by the family to the child. Davidson (2005) reports that young children, due to their developmental characteristics, focus on immediate results rather than long-term results in their responses to their well-being. Gifts, toys, material things, and the instant pleasure of owning them are important in the lives of young children. Young children may respond negatively when something they don’t like that day. Daily life affects young children very quickly. This creates a measurement problem in studies involving young children. In the Life Standard dimension of the SWB-YC, it is asked whether the family generally meets the child’s wishes.

Life satisfaction is the third dimension of the SWB-YC. Studies with young children report that children talk about fun, personal achievements, dreams (Koch, 2018; Permiakova et al., 2016). In line with these findings, the Life Satisfaction also includes entertainment, personal achievements and dreams. Dreaming makes children happy (Gündoğan, 2019). Emotional well-being is related to the characteristic features of children such as hope, love, pleasure, love of learning (Shoshani, 2019). The three dimensions of the SWB-YC are compatible with other empirical studies (Koch, 2018; Lam & Comay, 2020; Permiakova et al., 2016; Sandseter & Seland, 2016, 2018; Shoshani, 2019; Storli & Sandseter, 2019).

The SWB-YC shows good psychometric properties. Scales show high internal consistency. The factor structure of the SWB-YC was consistent with the theoretical findings. Reliability study results show that the scale has the necessary conditions, except for one item in the item-total correlation. Construct validity results show that the scale’s goodness-of-fit index values are at an acceptable level and that convergent and discriminant validity conditions are met, except for the AVE coefficient (Yaşlıoğlu, 2017).

Concurrent validity results revealed a relationship between the PERIK Self-assertiveness and the SWB-YC Life Standard. Children who scored high in the Life Standard were rated high in the Self-assertiveness by their teachers. Family facilities provide a richly stimulating home and classroom environment. Stimulating environments also positively affect the child’s cognitive performance, success and self-esteem (Christensen et al., 2014; Page, 2002). The socio-economic status of the family affects the child’s self-confidence (Filippin & Paccagnella, 2012). No relationship was found between the PERIK Social Performance and the subscales of the SWB-YC. This may be due to the fact that the PERIK Social Performance only measures the child’s relationship with her friends, while the SWB-YC Positive Relationships with Others includes the child’s relationships with adults as well as with her friends. It is stated that there is a weak relationship between self-control and life satisfaction (Shoshani & Slone, 2017). Therefore, no relationship could be found between the PERIK Self-control and the subscales of the SWB-YC. No correlation was found between the PERIK Emotional Stability and the subscales of the SWB-YC. Items in the PERIK Emotional Stability include an adult view of the child’s emotional state under or after stress. Life satisfaction relates to the quality of coping with stress, not its frequency (Fiorelli, 2011). Since the items in the PERIK Emotional Stability are more associated with emotional stability than coping with stress, there may be no correlation with the SWB-YC. No correlation was found between the PERIK Task Orientation and the subscales of the SWB-YC. Studies (Koch, 2018; Lam & Comay, 2020; Permiakova et al., 2016; Sandseter & Seland, 2016, 2018) show that the subjective well-being of young children is mostly about play, entertainment, and social relationships. Sandseter and Seland (2016) state that some young children do not like structured activities such as circle time. They want to play outside, decide what to do and with whom, to use the room and toys they want, to have as much time as they want. Since the SWB-YC is based on elements that are important in the subjective well-being of young children, there may not be a relationship with the PERIK Task Orientation. Curiosity is poorly associated with emotional well-being (Shoshani, 2019). Therefore, no relationship could be found between the PERIK Pleasure in Exploring and the subscales of the SWB-YC. Perhaps one of the most important reasons for the lack of relationship between the SWB-YC and the PERIK is the different evaluators. Different evaluators may produce different results (Davidson, 2005; Vieira et al., 2018).

On the other hand, age and gender differences of the SWB-YC were similar to those in other studies (Davidson, 2005; Fiorelli, 2011; Mayr & Ulich, 2009; Shoshani & Slone, 2017). The six-year-olds scored higher than the younger children. The scores obtained from the scale were in favor of the girls.

In addition, it was found that the subjective well-being levels of young children did not differ according to parent education levels, family income levels and preschool attendance. There are mixed findings regarding the effect of parent education level on subjective well-being. Some studies have revealed that subjective well-being is positively affected as parental education level increases (Assari, 2018a; Loft & Waldfogel, 2021). Some studies also found that subjective well-being did not differ according to parental education levels (Schlechter & Milevsky, 2010). In this study, the fact that subjective well-being did not differ according to parental education level may be due to the low number of lower educated mothers. Mandemakers and Kalmijn (2014) states that lower educated mothers have more negative impact on their children’s psychological well-being.

It is stated that family income level is positively related to subjective well-being (Özdemir, 2012; Loft & Waldfogel, 2021). However, family income level alone is not effective on the child’s subjective well-being. Factors such as parent education level, parents’ behaviors also come into play (Mayer, 2010). The higher the parental education level, the higher the family income (Assari, 2018b). The low number of families with lower incomes and the high level of parental education in this study may be the reason why no difference was found. Perhaps the effect of low family income in early childhood on the child’s subjective well-being may become more evident in later ages (Parkes et al., 2016).

In this study, preschool attendance did not have an effect on subjective well-being. This may be due to the low impact of pre-school education on subjective well-being (Bozgün & Akın-Kösterelioğlu, 2020) or the fact that the effects of pre-school attendance become more pronounced at later ages, as in family income (Reynolds et al., 2007). The low level of long-term pre-school attendance in this study may have also revealed this result. Entering preschool at an early age can positively affect subjective well-being (Singh & Mukherjee, 2019) or vice versa (Kaiser & Bauer, 2019). In addition, the quality of preschool education institutions is determinative in the subjective well-being of children, such as the child-staff ratio and the child-staff relationship (Love et al., 1996).

The SWB-YC is a self-report scale consisting of three dimensions and 22 questions. The fact that both the reliability coefficients of the SWB-YC and other criteria for validity are at a good level indicates that an acceptable valid and reliable scale has been reached. As a result, a valid and reliable scale for young children has emerged.

There are some limitations in this study. This study is limited to children aged 3–6 in a province. Comparisons can be made by applying the SWB-YC to other provinces and other countries. The relationship of the SWB-YC with different variables such as characteristics of children can be examined. The SWB-YC can be used to measure the outcomes of different experiences of participation, Positive Education etc. (Shoshani & Slone, 2017). The SWB-YC was developed from the findings of studies carried out with structured and unstructured methods with young children. Conducting studies on the subjective well-being of young children using different methods will provide us with more information on this subject.

5 Implications for Practices

The SWB-YC was developed to reveal the general subjective well-being of young children. Previous studies were aimed at revealing subjective well-being in a certain environment (such as school). In this respect, it is thought that it will contribute to the field. The life of young children consists of different environments such as school, home, outdoor environments. This study is important in terms of measuring the subjective well-being of children in different environments. In addition, this study is important in terms of showing the factors that affect the subjective well-being of young children. Young children give importance to different things than older children. Listening to the voices of young children ensures that children’s development is better in all areas.

References

Abbasi, A. Z., Shamim, A., Ting, D. H., Hlavacs, H., & Rehman, U. (2021). Playful-consumption experiences and subjective well-being: Children’s smartphone usage. Entertainment Computing, 36, 100390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2020.100390

Andresen, S., Bradshaw, J., & Kosher, H. (2019). Young children’s perceptions of their lives and well-being. Child Indicators Research, 12, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9551-6

Assari, S. (2018a). Parental educational attainment and mental well-being of college students: Diminished returns of blacks. Brain Sciences, 8(11), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8110193

Assari, S. (2018b). Parental education better helps white than black families escape poverty: National survey of children’s health. Economies, 6, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies6020030

Bozgün, K., & Akın-Kösterelioğlu, M. (2020). Variables affecting social-emotional development, academic grit and subjective well-being of fourth-grade primary school students. Educational Research and Reviews, 15(7), 417–425. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2020.4025

Christensen, D. L., Schieve, L. A., Devine, O., & Drews-Botsch, C. (2014). Socioeconomic status, child enrichment factors, and cognitive performance among preschool-age children: Results from the follow-up of growth and development experiences study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(7), 1789–1801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.02.003

Coffey, J. K., Warren, M. T., & Gottfried, A. W. (2015). Does infant happiness forecast adult life satisfaction? Examining subjective well-being in the first quarter century of life. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 16(6), 1401–1421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9556-x

Cummins, R. A., & Lau, A. L. D. (2005). Personal well-being index-school children (PWI-SC) manual (3rd ed.). Deakin University.

Davidson, K. (2005). The development and validation of the preschoolers’ subjective well-being scale (Master Thesis). Mount Saint Vincent University. Retrieved from https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/thesescanada/vol2/002/MR17504.PDF?oclc_number=263468174

Ebesutani, C., Regan, J., Smith, A., Reise, S., Higa-McMillan, C., & Chorpita, B. F. (2012). The 10-item positive and negative affect schedule for children, child and parent shortened versions. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34, 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-011-9273-2

Filippin, A., & Paccagnella, M. (2012). Family background, self-confidence and economic outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31, 824–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2012.06.002

Fiorelli, J. A. (2011). Pretend play, coping, and subjective well-being in children: A follow-up study (Master Thesis). Case Western reserve Unıversıty. Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_etd/send_file/send?accession=case1301585283&disposition=inline

Gündoğan, A. (2019). I would like to live over the rainbow: Dreams of young children. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 17(4), 434–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X19879210

Hinkley, T., Teychenne, M., Downing, K. L., Ball, K., Salmon, J., & Hesketh, K. D. (2014). Early childhood physical activity, sedentary behaviors and psychosocial well-being: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 62, 182–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.02.007

Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial development of the student's life satisfaction scale. School Psychology International, 12(3), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034391123010

Huppert, F. A., & So, T. T. C. (2013). Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research, 110(3), 837–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7

Kaiser, M., & Bauer, J. M. (2019). Preschool child care and child well-being in Germany: Does the migrant experience differ? Social Indicators Research, 144, 1367–1390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02064-5

Kennedy-Behr, A., Rodger, S., & Mickan, S. (2015). Play or hard work: Unpacking well-being at preschool. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 38, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.12.003

Koch, A. B. (2018). Children’s perspectives on happiness and subjective well-being in preschool. Children & Society, 32, 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12225

Laevers, F. (2005). Well-being and involvement in care settings. A process-oriented self-evaluation instrument. Retrieved from https://www.kindengezin.be/img/sics-ziko-manual.pdf

Lam, L., & Comay, J. (2020). Using a story completion task to elicit young children’s subjective well-being at school. Child Indicators Research, 13, 2225–2239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09745-5

Loft, L., & Waldfogel, J. (2021). Socioeconomic status gradients in young children's well-being at school. Child Development, 92(1), e91–e105. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13453

Love, J. M., Schochet, P. Z. & Meckstroth, A. L. (1996). Are they in any real danger? What research does-and doesn't-tell us about child care quality and children's well-being. Child Care Research and Policy Papers. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED415030

Mandemakers, J. J., & Kalmijn, M. (2014). Do mother’s and father’s education condition the impact of parental divorce on child well-being? Social Science Research, 44, 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.12.003

Mayer, S. E. (2010). Revisiting an old question: How much does parental income affect child outcomes? Focus, 27(2), 21–26.

Mayr, T., & Ulich, M. (2009). Social-emotional well-being and resilience of children in early childhood settings-PERIK: An empirically based observation scale for practitioners. Early Years: An International Research Journal, 29(1), 45–57.

Nikolova, M., & Nikolaev, B. N. (2021). Family matters: The effects of parental unemployment in early childhood and adolescence on subjective well-being later in life. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 181, 312–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2018.05.005

Özdemir, Y. (2012). Examining the subjective well-being of adolescents in terms of demographic variables, parental control, and parental warmth. Education and Science, 37(165), 20–33.

Page, M. S. (2002). Technology-enriched classrooms. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 34(4), 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2002.10782358

Parkes, A., Sweeting, H., & Wight, D. (2016). What shapes 7-year-olds’ subjective well-being? Prospective analysis of early childhood and parenting using the growing up in Scotland study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51, 1417–1428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1246-z

Permiakova, M. Y., Tokarskaya, L. V., & Yershova, I. A. (2016). The research of subjective sense of happiness in senior preschoolers. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 233, 100–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.10.153

Przybylski, A. K., & Weinstein, N. (2019). Digital screen time limits and young children's psychological well-being: Evidence from a population-based study. Child Development, 90(1), e56–e65. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13007

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Ellert, U., & Erhart, M. (2007). Gesundheitsbezogene Lebensqualität von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Bundesgesundheitsbl., 50, 810–818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-007-0244-4

Rees, G. (2019). Top-line analysis and feasibility study on mental health and well-being using millennium cohort study data (research report). Cardiff: Welsh Government. Retrieved from https://gov.wales/analysis-mental-health-and-well-being-using-millennium-cohortstudy-data

Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., Ou, S. R., Robertson, D. L., Mersky, J. P., Topitzes, J. W., & Niles, M. D. (2007). Effects of a school-based, early childhood intervention on adult health and well-being: A 19-year follow-up of low-income families. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 161(8), 730–739. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.8.730

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Saltalı, N. D., Erbay, F., Işık, E. & İmir, H. M. (2018). Turkish validation of social emotional well-being and resilience scale (PERIK). International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 10(5), 525-533. https://doi.org/10.26822/iejee.2018541302.

Sandseter, E. B. H., & Seland, M. (2016). Children’s experience of activities and participation and their subjective well-being in Norwegian early childhood education and care institutions. Child Indicators Research, 9, 913–932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-015-9349-8

Sandseter, E. B. H., & Seland, M. (2018). 4-6 year-old children’s experience of subjective well-being and social relations in ECEC institutions. Child Indicators Research, 11, 1585–1601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-017-9504-5

Schlechter, M., & Milevsky, A. (2010). Parental level of education: Associations with psychological well-being, academic achievement and reasons for pursuing higher education in adolescence. Educational Psychology, 30(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410903326084

Seligson, J. L., Huebner, E. S., & Valois, R. F. (2003). Preliminary validation of the brief multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale (BMSLSS). Social Indicators Research, 61, 121–145. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021326822957

Shoshani, A. (2019). Young children’s character strengths and emotional well-being: Development of the character strengths inventory for early childhood (CSI-EC). The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(1), 86–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1424925

Shoshani, A., & Slone, M. (2017). Positive education for young children: Effects of a positive psychology intervention for preschool children on subjective well being and learning behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1866. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01866

Singh, R., & Mukherjee, P. (2019). Effect of preschool education on cognitive achievement and subjective wellbeing at age 12: Evidence from India. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 49(5), 723–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2018.1453349

Storli, R., & Sandseter, E. B. H. (2019). Children's play, well-being and involvement: How children play indoors and outdoors in Norwegian early childhood education and care institutions. International Journal of Play, 8(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2019.1580338

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive Medicine Reports, 12, 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.003

Vieira, M. E. B., Formiga, C. K. M. R., & Linhares, M. B. M. (2018). Quality of life reported by pre-school children and their primary caregivers. Chid Indicators Research, 11, 1967–1982. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-017-9518-z

Yaşlıoğlu, M. M. (2017). Factor analysis and validity in social sciences: Application of exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Istanbul University Journal of the School of Business, 46, 74–85.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Necla Acun Kapıkıran for her valuable contributions to scale development. My thanks go to Neslihan Durmuşoğlu Saltalı for PERIK. I would also like to thank the children and their teachers for their cooperation in my research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gündoğan, A. “Hear my Voice”: Subjective Well-Being Scale for Young Children (SWB-YC). Child Ind Res 15, 747–761 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09877-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09877-2