Abstract

Iron is an essential trace metal for nearly all infectious microorganisms, and host defense mechanisms target this dependence to deprive microbes of iron. This review highlights mechanisms that are activated during infections to restrict iron on mucosal surfaces, in plasma and extracellular fluid, and within macrophages. Iron overload disorders, such as hereditary hemochromatosis or β-thalassemia, interfere with iron-restrictive host responses, and thereby cause increased susceptibility to infections with microbes that can exploit this vulnerability. Anemia of inflammation (formerly known as anemia of chronic diseases) is an “off-target” effect of host defense wherein inflammatory cytokines shorten erythrocyte lifespan by activating macrophages, prioritize leukocyte production in the marrow, and induce hepcidin to increase plasma transferrin saturation and the concentration of non-transferrin-bound iron.

Similar content being viewed by others

Overview

In this review, I discuss the biological role of iron in host defense against infections and then describe clinical conditions where disorders of iron metabolism make patients susceptible to infections. Although older material is briefly summarized to provide context, emphasis is placed on recent developments in this area.

Iron and the origin of life

Iron is an essential component of nearly all living organisms, with rare exceptions such as certain Lactobacilli [1]. One explanation for the ubiquity of iron is that it was the catalytic element that allowed the formation of macromolecules from CO2 and H2, which gave rise to early life forms. According to the Wächtershäuser [2] hypothesis, hydrothermal vents in primordial oceans contained hot water with high concentrations of both CO2 and H2, flowing through porous rock containing pyrite, FeS2, which catalyzed the formation of carbon-based macromolecules. Some elements of this hypothesis have been contested and further refined [3]. Nevertheless, it accounts very well for the universal metabolic role of catalytic iron in the biosphere.

Later, the evolution of photosynthesis led to a dramatic increase of ambient oxygen concentrations causing iron to oxidize and precipitate in its insoluble Fe3+ (ferric) form [4]. As a result, iron availability to biological organisms greatly decreased. Inside cells, where the oxygen concentration is lower and concentrations of reducing substances are high, iron continues to function as a crucial catalyst of essential metabolic processes. The versatility of iron in its biocatalytical role is facilitated by the modulation of its redox potential by iron-binding proteins and organic binders such as heme.

In those biological niches where iron availability was very low, microbes evolved mechanisms that allowed them to assimilate iron even at low ambient concentrations. Iron uptake is enhanced by mechanisms that increase the solubility of iron, e.g., by lowering the pH or reducing the iron to Fe2+, followed by high affinity uptake of Fe2+. Some microbes use enzymatic systems or receptor mediated uptake of host ferroproteins that allow them to extract iron from proteins of hosts and prey. Alternatively, microbes secrete siderophores, small organic molecules that bind iron with very high affinity, followed by uptake of iron-siderophore complexes. The maintenance and operation of microbial iron-acquisition systems incurs substantial metabolic costs and the risk that the mechanisms will be countered by host defenses or, in the case of siderophores, may diffuse away to be pirated by niche competitors. To confer an evolutionary survival benefit, such costs must be outweighed by the advantages they confer in a particular niche. In other niches iron was more abundant and these mechanisms did not evolve or were secondarily lost. In a common evolutionary compromise, the mechanisms are encoded in the genome of some organisms but may require activation by low environmental iron concentrations, negating some but not all of the metabolic costs.

Infections and the contest over iron

For the purposes of this review, infection is defined as the entry of microbes into tissues of multicellular hosts where these microbes are not normally present. Although some of the mechanisms I will describe have their analogs in plants and invertebrates, this review will focus on human infections, and their most informative model, infections in the laboratory mouse. Compared to the very low estimated concentration of soluble environmental iron (Fe3+) in water, estimated at 10−17 M, mammalian extracellular fluid contains of the order of 10−5 M iron and red blood cells contain about 10−2 M iron! However, nearly all mammalian iron is complexed within proteins and therefore not readily accessible to infecting microbes.

Pathogenic microbes have evolved specialized mechanisms for obtaining iron from the host during infections (“iron piracy” [5]), but the mammalian host has evolved multiple mechanisms of innate immunity that limit the availability of essential nutrient iron to infecting microbes, “iron-targeted nutritional immunity”. I will describe these host defense mechanisms in the sequence as they may appear to microbes that penetrate from mucosal surfaces, spread through the bloodstream and are ingested by phagocytes (Table 1).

Mucosal surfaces contain iron-sequestering proteins

Mucosal surfaces, including the epithelia covering the eyes, oropharynx, gastrointestinal, respiratory and urogenital tracts are covered with a thin layer of fluid endowed with mechanical and chemical properties that interfere with microbial attachment and survival. The fluid contains mucins that entrap microbes as well as antimicrobial substances such as lysozyme or defensins that damage or destroy many microbes. Continued secretion of mucosal fluid from glands (e.g., tears) or the movement of fluid by beating cilia generates flow across the mucosal surface which eventually moves microbes out of the body or to locations where they are destroyed (e.g., to the low pH environment of the stomach). Some mucosal fluids also contain high concentrations of lactoferrin and lipocalin 2 (siderocalin) that bind ferric iron and siderophore-bound iron, respectively, and are thought to limit the availability of essential iron to microbes.

Lactoferrin

Lactoferrin [6] is closely related to the plasma iron-carrier protein, transferrin. Unlike transferrin which evolved to deliver iron to cells via the transferrin receptor 1 and releases iron in acidified endosomes at pH below 5.5, lactoferrin does not release its iron even at pH 3.5, a property that assures iron sequestration even in infected tissues where the pH is commonly highly acidic. Like transferrin, lactoferrin binds one ferric iron atom in each of its two lobes. Among human fluids, high concentrations (~ mg/ml range) are found in colostrum, milk and tears, where iron-free apolactoferrin is secreted by the exocrine glands that generate these fluids. Lactoferrin is also found in pus, as it is released from the lactoferrin- and lysozyme-rich secondary granules of neutrophils. Lactoferrin in milk and colostrum is largely iron-free and it partially survives interactions with digestive enzymes [7] so that it is detectable at high concentration in the stool of breast-fed infants [8]. The composition of intestinal microbiota in infants appears to be modulated by lactoferrin in breast milk [8]. Mice lacking lactoferrin have a higher incidence of spontaneous staphylococcal abscesses in the skin despite normal neutrophil-mediated killing of these organisms, suggesting that mucosal lactoferrin serves as a nonredundant part of the body surface barrier against these and likely other microbes [9].

Lipocalin-2

Lipocalin-2 (also called siderocalin or NGAL for neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin) is a member of a structural family of small proteins containing a “calyx”, i.e., cup-like structure that binds and transports small hydrophobic organic molecules. The primary function of lipocalin-2 is to sequester bacterial siderophores such as enterobactin that avidly bind ferric iron [10]. Enterobactin is secreted by certain E. coli and other enteric Gram-negative bacteria, then recaptured by the same or different bacteria that can extract its iron. Another potential function of lipocalin-2, demonstrated in human urinary tract infections, is to trap endogenous human catechol metabolites and use them as chelators to sequester ferric iron from infecting bacteria [11]. Lipocalin-2 is secreted in humans and mice by various epithelia and by activated neutrophils and macrophages. In mice, lipocalin-2 is also an acute phase protein secreted by hepatocytes. Mice lacking lipocalin-2 in all tissues show increased mortality during E. coli sepsis or pneumonia [12, 13]. Lipocalin-2 is also required for optimal resistance in a mouse model of Klebsiella pneumonia, where tissue-selective ablation of lipocalin-2 showed that both neutrophil and epithelial lipocalin-2 protect additively against dissemination of infection [14].

Iron is depleted from extracellular fluid during infection and inflammation

Iron homeostasis in extracellular fluid

The human body contains 3–4 g of iron but most of it is intracellular, in hemoglobin of erythrocytes (about 2.0–2.5 g), in ferritin within hepatocytes and macrophages (about 0.5–1 g), and in myoglobin, ferritin and iron-containing enzymes in other cell types (totaling about 0.5 g). Blood plasma contains only a few mg of iron, nearly all of it bound to the iron-carrier protein—transferrin—whose two binding sites are on the average 20–40% occupied by ferric atoms. Although the microvascular endothelium separates blood plasma from extracellular fluid, there is no evidence that this barrier affects the distribution of iron in most tissues, except for the central nervous system. In iron metabolism, blood plasma and extracellular fluid are a transit compartment that serves to move iron (about 25 mg/day) from its sources to its sites of utilization. Major iron sources include recycling of iron from senescent erythrocytes and other senescent cells by macrophages, intestinal iron absorption, and release of stored iron from hepatocytes. In all these tissues, iron is exported to extracellular fluid by the sole known cellular iron exporter ferroportin. The cellular concentrations of ferroportin are regulated by the amount of heme or iron within the cells, but also by the iron-regulatory hormone hepcidin which blocks iron export by binding to ferroportin and inducing its endocytosis and proteolysis. At higher concentrations of hepcidin, direct occlusion of ferroportin may also be an important mechanism of inhibition of cellular iron export.

Quantitatively, the main sites of iron utilization are bone marrow erythroid precursors involved in hemoglobin synthesis, and to a much lesser extent, other cells that undergo cell division or turnover of their ferroproteins. The iron in extracellular fluid turns over every 2–3 h, and the concentration of iron there depends on the balance between iron delivery to, and the consumption of iron from extracellular fluid. Remarkably, the concentration of iron in plasma and extracellular fluid is normally maintained in the range of 10–30 µM. The relative stability of extracellular iron concentration is a result of feedback regulation of iron flow into extracellular fluid by the interaction of the iron-regulatory hormone hepcidin with the cellular iron exporter ferroportin. An additional stabilizing influence is the strong dependence of erythropoiesis on the concentration of iron-bound transferrin, so that erythropoiesis (and the consumption of iron) is inhibited when iron concentration decreases below 10 µM.

Regulation of extracellular iron concentration during infection or inflammation

Within hours of infection or other inflammatory stimuli, plasma iron concentrations decrease, often below 10 µM. This response is referred to as “hypoferremia of inflammation”, and has been documented in humans, other mammals, and other vertebrates including fish. A common mechanism of hypoferremia of inflammation is a cytokine-driven increase in hepcidin [15] that downregulates ferroportin and thereby decreases iron flow into extracellular fluid from all its sources. Thus, under the influence of increased concentrations of hepcidin, recycled iron is retained in macrophages of the liver and the spleen, and iron absorption is decreased. The hypoferremia of inflammation is absent [16, 17] or greatly attenuated [18] in hepcidin knockout (KO) mice. The inflammatory increase in hepcidin is mainly caused by increased concentrations of IL-6 (interleukin-6) [19], inducing the transcription of the hepcidin gene through the JAK2/STAT3 [20,21,22] pathway. Synergistic effect of the BMP pathway on hepcidin transcription also contributes to the maximal hepcidin induction by inflammation [23]. The role of IL-6 is important in many models of infection and inflammation [19, 24] but in some models other cytokines may partially replace its stimulatory effect on hepcidin [17]. Hepcidin-independent effects of inflammation on ferroportin have also been reported in mice treated with lipopolysaccharide [18, 25] but it is not clear what role they play during microbial infections (Fig. 1).

Hepcidin protects against infections by preventing the generation of non-transferrin-bound iron

Genetic iron overload disorders

Hereditary hemochromatosis [26, 27] is a variably severe iron overload disorder resulting from genetic deficiency of hepcidin because of mutations in genes encoding hepcidin regulators (HFE, transferrin receptor 2, hemojuvelin) or hepcidin itself. Rarely, hereditary hemochromatosis results from dominant ferroportin mutations that cause resistance to hepcidin by impairing hepcidin binding to ferroportin or the resulting conformational change in ferroportin. In proportion to the severity of the disorder, untreated patients with hereditary hemochromatosis may suffer from organ damage caused by excessive intestinal iron absorption and tissue iron accumulation, including high concentrations of iron in extracellular fluid, often exceeding the binding capacity of transferrin. As transferrin saturation approaches 100%, iron binds instead to citrate, other organic acids and albumin. This form of iron, referred to as non-transferrin-bound iron (NTBI), is taken up by some tissues through NTBI transporters, resulting in excessive iron accumulation in hepatocytes, cardiac myocytes, and the endocrine glands. A similar pathological situation occurs in patients with iron-loading anemias, such as β-thalassemia, where hepcidin production is suppressed by substances such as—erythroferrone—a hormone secreted by the greatly expanded number of erythroid precursors. Iron overload in these anemias is further exacerbated in patients who require frequent transfusions, because blood contains 1 mg of iron per 1 ml of packed erythrocytes. Some patients with chronic liver disease, particularly those with hepatitis C infection, also develop an impairment of hepcidin synthesis, causing iron overload that may worsen the liver injury [28, 29]. Chronic liver disease can cause high transferrin saturation and appearance of NTBI in circulation [30].

Iron overload predisposes to severe infections with siderophilic bacteria

Patients with iron overload disorders are known to be susceptible to lethal infections with bacteria that are considered only moderately pathogenic in other settings. Two species of “siderophilic” bacteria are characteristic of such infections, Vibrio vulnificus and Yersinia enterocolitica. V. vulnificus is a Gram-negative bacterium associated with fish, crustaceans and mollusks in warm seawater, and can be transmitted to humans by ingestion of uncooked seafood or through wounds during handling of marine organisms [31]. It is particularly lethal (20–50% mortality) in individuals with iron overload [32, 33], whose condition is sometimes clinically silent and unrecognized at the time of infection. Remarkably, patients with iron overload experience a very rapid progression of infection, with high rate of V. vulnificus proliferation and severe endotoxemia. Another Gram-negative bacterium causing severe infections in iron-overloaded patients is Yersinia enterocolitica, which causes a characteristic disease with disseminated tissue abscesses and sepsis [34,35,36].

Mouse models of hepcidin deficiency implicate non-transferrin-bound iron as a stimulus for infections with siderophilic bacteria

The rapidly lethal course of human V. vulnificus infection in iron-overloaded patients is reproduced in a mouse model of V. vulnificus infection where iron-overloaded hepcidin-1 knockout mice die of sepsis within 12 h of subcutaneous inoculation with these bacteria [37], with large clusters of bacteria growing in the area of injection and disseminating into organs. The mice were protected or rescued by treatment with the hepcidin analog PR-73, which lowered the concentration of extracellular iron. In a subsequent study, the species of iron stimulating the rapid proliferation of V. vulnificus was shown to be NTBI [38].

Hepcidin-1 knockout mice infected orally with the O9 strain of Yersinia enterocolitica also provided a faithful model of the corresponding human infection, manifesting disseminated abscess formation and a lethal course [38] while wild-type control mice were resistant to these bacteria. Remarkably, the generally more pathogenic O8 strain, which is equipped with a “pathogenicity island” of genes encoding siderophores and other factors, caused a milder disease in iron-overloaded mice which was not different from that in wild-type mice. As with V. vulnificus, Y. enterocolitica, proliferation was strongly stimulated by NTBI, but not by iron bound to transferrin. In view of these findings, the “siderophilic” trait can be interpreted as a form of bacterial adaptation to environments containing high concentrations of readily available iron, such as NTBI. Such siderophilic bacteria acquired or evolved fewer genes for metabolically costly pathways of iron-acquisition in exchange for more rapid growth when iron is abundant. Infections of iron-overloaded hosts with such bacteria may be an unfortunate byproduct of such adaptation. The molecular mechanisms that allow bacteria to sense iron-rich environments and initiate rapid growth remain to be characterized. These mechanisms may be more widespread than is generally recognized, as Klebsiella pneumoniae [39] and Escherichia coli (manuscript in preparation) also manifest greatly enhanced, iron-dependent pathogenicity in hepcidin-1 knockout mice.

Viewed in this context, high concentrations of hepcidin during infection serve to clear NTBI from extracellular fluid, so that NTBI is not available to stimulate the growth of bacteria (Figs. 2, 3). Preventing the formation of NTBI is a particular challenge during infections because of an imbalance between iron supply and iron consumption. Infection-related destruction and phagocytosis of erythrocytes and other cells liberates more iron while inflammatory cytokines inhibit erythropoiesis [40, 41] and therefore inhibit the consumption of iron from blood plasma and extracellular space. As a result, in the absence of hepcidin, serum iron concentrations increase after an inflammatory stimulus (Fig. 2), as is readily demonstrable in hepcidin knockout mice [16]. In wild-type mice and humans with normal iron regulation, high concentrations of hepcidin inhibit the release of recycled iron from macrophages and therefore decrease the potential generation of NTBI (Fig. 3). Based on the studies in mouse models of iron overload [38, 42], patients with siderophilic infections in the setting of genetic iron overload disorders or chronic liver disease may benefit from treatment with hepcidin agonists when these become available for human use.

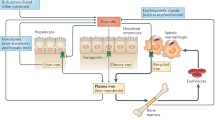

Generation of non-transferrin-bound iron (NTBI) in hepcidin-deficient patients is enhanced during infection. General inflammatory regulators are shown in grey, iron-regulatory pathway in green, iron flows in blue and erythropoiesis and erythrocytes in red. The lack of hepcidin allows high expression of ferroportin and rapid return of recycled iron from hemolyzed erythrocytes and damaged tissue into plasma and extracellular fluid. At the same time, the consumption of iron for erythropoiesis is inhibited by inflammatory cytokines, further raising iron concentrations and generating NTBI

Hepcidin increase during infection prevents the generation of NTBI. General inflammatory regulators are shown in grey, iron-regulatory pathway in green, iron flows in blue and erythropoiesis and erythrocytes in red. High hepcidin concentrations decrease ferroportin on macrophages, so that iron recycled from hemolyzed erythrocytes and damaged tissue is retained in macrophages and not released to plasma and extracellular fluid. Retention of iron in macrophages compensates also for the decreased demand of suppressed erythropoiesis for iron

Phagocytes

Phagocytic cells play an important part in host resistance to infections by chemotaxis to the site of infection, and endocytosis, killing and decomposition of infecting microbes. The two main classes of phagocytes, the short-lived neutrophils (also referred to as polymorphonuclear leukocytes, granulocytes) and the long-lived macrophages perform similar host defense tasks, but the neutrophils are end-stage differentiated cells with limited metabolic functions, making them inhospitable to microbes seeking to parasitize them. By contrast, macrophages are highly metabolically active, and rich in various metabolic intermediates that can be utilized by intracellular parasites, including such common infectious microorganisms as Salmonella, Mycobacteria and Legionella.

Nramp1, a gene with variants associated with intracellular infections of macrophages, encodes a divalent metal transporter in phagocytes

Early studies of the genetic basis of resistance to infections uncovered differences among mouse strains in their susceptibility to intracellular infections with a group of diverse microbes that included Leishmania, Mycobacteria and Salmonella [43] but not virulent strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis [44]. Positional cloning of the gene responsible, named natural-resistance-associated macrophage protein 1, eventually revealed it as a divalent metal transporter, homologous to divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1). Whereas, DMT-1 mediates apical iron uptake in duodenal enterocytes and also transports iron taken up by the transferrin receptor from the endosome to the cytoplasm, Nramp1 does not play a substantial role in baseline iron homeostasis. Remarkably, Nramp1 expression was highly inducible by inflammatory stimuli, such as the combination of lipopolysaccharide and interferon-γ. The protein was located in phagosomal membranes of macrophages and the tertiary granules of neutrophils that transfer Nramp1 to cellular and phagosomal membranes. The mouse strains susceptible to the three intracellular pathogens contained Nramp with the D169G mutation, which rendered the protein unstable. In humans, there is no direct counterpart of this mutation but certain polymorphisms have been linked to increased susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis [45].

Mechanism of action of Nramp1

In the two decades since the discovery of Nramp1 (now also called SLC11a1) multiple controversies about the functions of this protein arose. The weight of the evidence now indicates that Nramp1 transports iron and manganese out of the phagocytic vacuole into the cytoplasm [46], thereby depleting the phagosome of these essential metals. This view is supported by most of the direct experimental evidence, by the involvement of Nramp1 in iron recycling from senescent erythrocytes [47], by the similarity of Nramp1 to DMT1 whose transport properties are well characterized, and by the evidence that the function of Nramp1 may be carried out in teleost fish by a duplicated paralog of DMT1 [48]. The lack of iron and manganese in the phagosomal vacuole would inhibit the replication of resident intracellular organisms and could impair their ability to detoxify reactive oxygen species generated by the phagocyte oxidase.

The effect of hepcidin on intracellular infections

Macrophages that are actively recycling iron from senescent erythrocytes or other damaged or senescent cells express ferroportin, which allows them to export excess iron back to blood plasma or extracellular fluid. The macrophages, rich in iron and other breakdown products are targeted by Salmonella [49] and likely also by other intracellular microbes seeking nutrients. When hepcidin rises during infections, it induces the endocytosis and proteolysis of ferroportin, thereby causing the retention of iron in cytoplasmic ferritin. It is therefore reasonable to expect that, while high plasma hepcidin concentrations act to sequester iron from extracellular organisms, the increased availability of iron within phagocytes may promote the survival of intracellular microbes. Although there is evidence for this effect in cultured macrophages [50], studies in mice have not supported the enhancement of intracellular infection by high concentrations of hepcidin [38, 51]. Possible explanations include microbial factors that take over the control of iron export in infected macrophages [51] or compartmentalization of iron within macrophages that limits its availability to intracellular microbes.

Anemia of infection/inflammation

Patients suffering from chronic infections or inflammatory disorders commonly develop a normocytic normochromic anemia, with characteristic hypoferremia. This usually moderate anemia is caused by decreased production of erythrocytes coupled with a slight decrease in erythrocyte survival [52]. Viewed in the context of iron-targeted nutritional immunity, anemia of infection/inflammation is an off-target effect. The production of erythrocytes has evolved to be very sensitive to decreased availability of iron, whether it is from true iron deficiency or inflammatory iron restriction. Inhibition of erythropoiesis by hypoferremia makes sense because it preserves iron for other metabolic uses during infection, and may facilitate the diversion of bone marrow progenitors towards the production of leukocytes for host defense. Experimental evidence indicates that erythropoiesis is uniquely sensitive to hypoferremia [53] and that other tissues can utilize iron even when it is available at much lower concentrations than normal. Because of the relatively long lifespan of erythrocytes, 4 months, the anemia takes many weeks to develop, unless there is also greatly increased destruction of erythrocytes or blood loss, as is seen in a rapidly developing variant of anemia of infection/inflammation, anemia of critical illness [54]. Hypoferremia is not the only consequence of inflammation that limits erythropoiesis. Inflammatory cytokines directly suppress erythropoiesis, likely to increase leukocyte production, and also activate macrophages for increased erythrophagocytosis [40, 55].

Summary

Iron is an essential trace element which is in short supply in many environments. Specific innate immune mechanisms further limit iron availability to microbes during infection, at the cost of impairing erythropoiesis. Siderophilic microbes have evolved to grow rapidly in niches where iron is more available, and these microbes may cause severe infections in patients whose ability to restrict the iron supply is impaired genetically or as a result of disease or treatment. Pharmacological targeting of iron to treat infections with siderophilic microbes may be a viable therapeutic strategy.

Change history

02 December 2017

The author would like to correct the error in the “Abstract” section of original publication as given below.

References

Archibald F. Lactobacillus plantarum, an organism not requiring iron. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1983;19:29–32.

Huber C, Wächtershäuser G. Activated acetic acid by carbon fixation on (Fe, Ni)S under primordial conditions. Science. 1997;276:245–7.

Camprubi E, Jordan SF, Vasiliadou R, et al. Iron catalysis at the origin of life. IUBMB Life. 2017;69:373–81.

Ilbert M, Bonnefoy V. Insight into the evolution of the iron oxidation pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 2013;1827:161–75.

Barber MF, Elde NC. Buried treasure: evolutionary perspectives on microbial iron piracy. Trends Genet. 2015;31:627–36.

Mayeur S, Spahis S, Pouliot Y, et al. Lactoferrin, a pleiotropic protein in health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2016;24:813–36.

de Oliveira SC, Bellanger A, Ménard O, et al. Impact of human milk pasteurization on gastric digestion in preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105:379–90.

Mastromarino P, Capobianco D, Campagna G, et al. Correlation between lactoferrin and beneficial microbiota in breast milk and infant’s feces. Biometals. 2014;27:1077–86.

Ward PP, Mendoza-Meneses M, Park PW, et al. Stimulus-dependent impairment of the neutrophil oxidative burst response in lactoferrin-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1019–29.

Sia AK, Allred BE, Raymond KN. Siderocalins: siderophore binding proteins evolved for primary pathogen host defense. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:150–7.

Shields-Cutler RR, Crowley JR, Miller CD, et al. Human metabolome-derived cofactors are required for the antibacterial activity of siderocalin in urine. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:25901–10.

Flo TH, Smith KD, Sato S, et al. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature. 2004;432:917–21.

Wu H, Santoni-Rugiu E, Ralfkiaer E, et al. Lipocalin 2 is protective against E. coli pneumonia. Respir Res. 2010;11:96.

Cramer EP, Dahl SL, Rozell B, et al. Lipocalin-2 from both myeloid cells and the epithelium combats Klebsiella pneumoniae lung infection in mice. Blood. 2017;129:2813–7.

Nicolas G, Chauvet C, Viatte L, et al. The gene encoding the iron regulatory peptide hepcidin is regulated by anemia, hypoxia, and inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1037–44.

Kim A, Fung E, Parikh SG, et al. A mouse model of anemia of inflammation: complex pathogenesis with partial dependence on hepcidin. Blood. 2014;123:1129–36.

Gardenghi S, Renaud TM, Meloni A, et al. Distinct roles for hepcidin and interleukin-6 in the recovery from anemia in mice injected with heat-killed Brucella abortus. Blood. 2014;123:1137–45.

Deschemin JC, Vaulont S. Role of hepcidin in the setting of hypoferremia during acute inflammation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61050.

Nemeth E, Rivera S, Gabayan V, et al. IL-6 mediates hypoferremia of inflammation by inducing the synthesis of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1271–6.

Pietrangelo A, Dierssen U, Valli L, et al. STAT3 is required for IL-6-gp130-dependent activation of hepcidin in vivo. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:294–300.

Verga Falzacappa MV, Vujic SM, Kessler R, et al. STAT3 mediates hepatic hepcidin expression and its inflammatory stimulation. Blood. 2007;109:353–8.

Wrighting DM, Andrews NC. Interleukin-6 induces hepcidin expression through STAT3. Blood. 2006;108:3204–9.

Verga Falzacappa MV, Casanovas G, Hentze MW, et al. A bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-responsive element in the hepcidin promoter controls HFE2-mediated hepatic hepcidin expression and its response to IL-6 in cultured cells. J Mol Med. 2008;86:531–40.

Rodriguez R, Jung CL, Gabayan V, et al. Hepcidin induction by pathogens and pathogen-derived molecules is strongly dependent on interleukin-6. Infect Immun. 2014;82:745–52.

Guida C, Altamura S, Klein FA, et al. A novel inflammatory pathway mediating rapid hepcidin-independent hypoferremia. Blood. 2015;125:2265–75.

Siddique A, Kowdley KV. Review article: the iron overload syndromes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:876–93.

Pietrangelo A. Hereditary hemochromatosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:393–408 (408 e391–e392).

Girelli D, Pasino M, Goodnough JB, et al. Reduced serum hepcidin levels in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2009;51:845–52.

Fujita N, Sugimoto R, Takeo M, et al. Hepcidin expression in the liver: relatively low level in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Mol Med. 2007;13:97–104.

de Feo TM, Fargion S, Duca L, et al. Non-transferrin-bound iron in alcohol abusers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1494–9.

Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus: death on the half shell. A personal journey with the pathogen and its ecology. Microb Ecol. 2013;65:793–9.

Barton JC, Acton RT. Hemochromatosis and Vibrio vulnificus wound infections. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:890–3.

Kuo C-H, Dai Z-K, Wu J-R, et al. Septic arthritis as the initial manifestation of fatal Vibrio vulnificus septicemia in a patient with thalassemia and iron overload. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53:1156–8.

Bergmann TK, Vinding K, Hey H. Multiple hepatic abscesses due to Yersinia enterocolitica infection secondary to primary haemochromatosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:891–5.

Hopfner M, Nitsche R, Rohr A, et al. Yersinia enterocolitica infection with multiple liver abscesses uncovering a primary hemochromatosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:220–4.

Vento S, Cainelli F, Cesario F. Infections and thalassaemia. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:226–33.

Arezes J, Jung G, Gabayan V, et al. Hepcidin-induced hypoferremia is a critical host defense mechanism against the siderophilic bacterium Vibrio vulnificus. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:47–57.

Stefanova D, Raychev A, Arezes J, et al. Endogenous hepcidin and its agonist mediate resistance to selected infections by clearing non-transferrin-bound iron. Blood. 2017;. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-03-772715.

Michels KR, Zhang Z, Bettina AM, et al. Hepcidin-mediated iron sequestration protects against bacterial dissemination during pneumonia. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e92002.

Libregts SF, Gutierrez L, de Bruin AM, et al. Chronic IFN-gamma production in mice induces anemia by reducing erythrocyte life span and inhibiting erythropoiesis through an IRF-1/PU.1 axis. Blood. 2011;118:2578–88.

Allen DA, Breen C, Yaqoob MM, et al. Inhibition of CFU-E colony formation in uremic patients with inflammatory disease: role of IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha. J Investig Med. 1999;47:204–11.

Arezes J, Nemeth E. Hepcidin and iron disorders: new biology and clinical approaches. Int J Lab Hematol. 2015;37(Suppl 1):92–8.

Forbes JR, Gros P. Divalent-metal transport by NRAMP proteins at the interface of host-pathogen interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:397–403.

North RJ, LaCourse R, Ryan L, et al. Consequence of Nramp1 deletion to mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5811–4.

Yuan L, Ke Z, Guo Y, et al. NRAMP1 D543N and INT4 polymorphisms in susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis: a meta-analysis. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;54:91–7.

Wessling-Resnick M. Nramp1 and other transporters involved in metal withholding during infection. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:18984–90.

Soe-Lin S, Apte SS, Mikhael MR, et al. Both Nramp1 and DMT1 are necessary for efficient macrophage iron recycling. Exp Hematol. 2010;38:609–17.

Neves JV, Wilson JM, Kuhl H, et al. Natural history of SLC11 genes in vertebrates: tales from the fish world. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:106.

Nix RN, Altschuler SE, Henson PM, et al. Hemophagocytic macrophages harbor Salmonella enterica during persistent infection. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e193.

Chlosta S, Fishman DS, Harrington L, et al. The iron efflux protein ferroportin regulates the intracellular growth of Salmonella enterica. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3065–7.

Willemetz A, Beatty S, Richer E, et al. Iron- and hepcidin-independent downregulation of the iron exporter ferroportin in macrophages during salmonella infection. Front Immunol. 2017;8:498.

Cartwright GE, Lee GR. The anaemia of chronic disorders. Br J Haematol. 1971;21:147–52.

Bullock GC, Delehanty LL, Talbot AL, et al. Iron control of erythroid development by a novel aconitase-associated regulatory pathway. Blood. 2010;116:97–108.

Hayden SJ, Albert TJ, Watkins TR, et al. Anemia in critical illness: insights into etiology, consequences, and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1049–57.

Means RT Jr. Pathogenesis of the anemia of chronic disease: a cytokine-mediated anemia. Stem Cells. 1995;13:32–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

TG is a scientific founder and a consultant for Intrinsic LifeSciences, La Jolla, USA; Silarus Pharma, La Jolla, USA and a consultant for Keryx Pharma, New York City, USA; Akebia Pharma, Cambridge, USA: La Jolla Pharmaceutical Company, La Jolla, USA; Gilead Sciences, San Dimas, USA.

Additional information

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-017-2385-z.

About this article

Cite this article

Ganz, T. Iron and infection. Int J Hematol 107, 7–15 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-017-2366-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-017-2366-2