Abstract

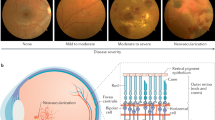

In diabetic retinopathy (DR), abnormalities in vascular and neuronal function are closely related to the local production of inflammatory mediators whose potential source is microglia. Adenosine and its receptors have been shown to possess anti-inflammatory properties that have only recently been studied in DR. Here, we review recent studies that determined the roles of adenosine and its associated proteins, including equilibrative nucleoside transporters, adenosine receptors, and underlying signaling pathways in retinal complications associated with diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Klein R, et al. The Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. II. Prevalence and risk of diabetic retinopathy when age at diagnosis is less than 30 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102(4):520–6.

Rungger-Brandle E, Dosso AA, Leuenberger PM. Glial reactivity, an early feature of diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(7):1971–80.

Zeng XX, Ng YK, Ling EA. Neuronal and microglial response in the retina of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Vis Neurosci. 2000;17(3):463–71.

Ammary-Risch NJ, Huang SS. The primary care physician's role in preventing vision loss and blindness in patients with diabetes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(3):281–3.

Cogan DG, Toussaint D, Kuwabara T. Retinal vascular patterns. IV. Diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1961;66:366–78.

Bursell SE, et al. Retinal blood flow changes in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and no diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37(5):886–97.

Benson WE, et al. Current popularity of pneumatic retinopexy. Retina. 1999;19(3):238–41.

Palmberg PF. Diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 1977;26(7):703–9.

Joussen AM, et al. A central role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. FASEB J. 2004;18(12):1450–2.

Barber AJ, et al. Neural apoptosis in the retina during experimental and human diabetes. Early onset and effect of insulin. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(4):783–91.

El-Remessy AB, et al. Experimental diabetes causes breakdown of the blood–retina barrier by a mechanism involving tyrosine nitration and increases in expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and urokinase plasminogen activator receptor. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(6):1995–2004.

El-Remessy AB, et al. Neuroprotective and blood–retinal barrier-preserving effects of cannabidiol in experimental diabetes. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(1):235–44.

Kern TS. Contributions of inflammatory processes to the development of the early stages of diabetic retinopathy. Exp Diabetes Res. 2007;2007:95103.

Ali TK, et al. Peroxynitrite mediates retinal neurodegeneration by inhibiting nerve growth factor survival signaling in experimental and human diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57(4):889–98.

Langmann T. Microglia activation in retinal degeneration. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(6):1345–51.

Lieth E, et al. Diabetes reduces glutamate oxidation and glutamine synthesis in the retina. The Penn State Retina Research Group. Exp Eye Res. 2000;70(6):723–30.

El-Remessy AB, et al. Cannabidiol protects retinal neurons by preserving glutamine synthetase activity in diabetes. Mol Vis. 2010;16:1487–95.

Ambati J, et al. Elevated gamma-aminobutyric acid, glutamate, and vascular endothelial growth factor levels in the vitreous of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(9):1161–6.

Lieth E, et al. Glial reactivity and impaired glutamate metabolism in short-term experimental diabetic retinopathy. Penn State Retina Research Group. Diabetes. 1998;47(5):815–20.

Kowluru RA, et al. Retinal glutamate in diabetes and effect of antioxidants. Neurochem Int. 2001;38(5):385–90.

Coyle JT, Puttfarcken P. Oxidative stress, glutamate, and neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 1993;262(5134):689–95.

Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19(8):312–8.

Madsen-Bouterse SA, Kowluru RA. Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy: pathophysiological mechanisms and treatment perspectives. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2008;9(4):315–27.

Aloisi F. Immune function of microglia. Glia. 2001;36(2):165–79.

Wood PL. Neuroinflammation: mechanisms and management. Totowa New York, NY: Humana Press; 2003.

Zeng HY, Green WR, Tso MO. Microglial activation in human diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(2):227–32.

Yang LP, et al. Baicalein reduces inflammatory process in a rodent model of diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(5):2319–27.

Liu W, et al. Expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and its receptor in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Curr Eye Res. 2009;34(2):123–33.

Ibrahim AS, et al. Genistein attenuates retinal inflammation associated with diabetes by targeting of microglial activation. Mol Vis. 2010;16:2033–42.

Joussen AM, et al. TNF-alpha mediated apoptosis plays an important role in the development of early diabetic retinopathy and long-term histopathological alterations. Mol Vis. 2009;15:1418–28.

Joussen AM, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs prevent early diabetic retinopathy via TNF-alpha suppression. FASEB J. 2002;16(3):438–40.

Krady JK, et al. Minocycline reduces proinflammatory cytokine expression, microglial activation, and caspase-3 activation in a rodent model of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2005. doi:10.2337/db(54.5.1559.

Ibrahim AS, et al. Retinal microglial activation and inflammation induced by amadori-glycated albumin in a rat model of diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60(4):1122–33.

Schalkwijk CG, et al. Plasma concentration of C-reactive protein is increased in type I diabetic patients without clinical macroangiopathy and correlates with markers of endothelial dysfunction: evidence for chronic inflammation. Diabetologia. 1999;42(3):351–7.

Tang J, et al. Retina accumulates more glucose than does the embryologically similar cerebral cortex in diabetic rats. Diabetologia. 2000;43(11):1417–23.

Wang AL, et al. AGEs mediated expression and secretion of TNF alpha in rat retinal microglia. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84(5):905–13.

Schalkwijk CG. Comment on “AGEs mediated expression and secretion of TNF alpha in rat retinal microglia” by Dr Wang et al. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:572–3. doi:4. author reply 574.

Quan Y, Du J, Wang X. High glucose stimulates GRO secretion from rat microglia via ROS, PKC, and NF-kappaB pathways. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85(14):3150–9.

Collis MG, Hourani SM. Adenosine receptor subtypes. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1993;14(10):360–6.

Fredholm BB, et al. Nomenclature and classification of purinoceptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46(2):143–56.

Feoktistov I, Goldstein AE, Biaggioni I. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase kinase in adenosine A2B receptor-mediated interleukin-8 production in human mast cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55(4):726–34.

Bong GW, Rosengren S, Firestein GS. Spinal cord adenosine receptor stimulation in rats inhibits peripheral neutrophil accumulation. The role of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(12):2779–85.

Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50(3):413–92.

Ohta A, Sitkovsky M. Role of G-protein-coupled adenosine receptors in downregulation of inflammation and protection from tissue damage. Nature. 2001;414(6866):916–20.

Awad AS, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor activation attenuates inflammation and injury in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290(4):F828–37.

Liou GI, et al. Mediation of cannabidiol anti-inflammation in the retina by equilibrative nucleoside transporter and A2A adenosine receptor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(12):5526–31.

Ibrahim AS, et al. A(2A) adenosine receptor (A(2A)AR) as a therapeutic target in diabetic retinopathy. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(5):2136–45.

Williams M. Challenges in developing P2 purinoceptor-based therapeutics. CIBA Found Symp. 1996;198:309–21.

Moser GH, Schrader J, Deussen A. Turnover of adenosine in plasma of human and dog blood. Am J Physiol. 1989;256(4 Pt 1):C799–806.

Carrier EJ, Auchampach JA, Hillard CJ. Inhibition of an equilibrative nucleoside transporter by cannabidiol: a mechanism of cannabinoid immunosuppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(20):7895–900.

Dunwiddie TV, Diao L. Regulation of extracellular adenosine in rat hippocampal slices is temperature dependent: role of adenosine transporters. Neuroscience. 2000;95(1):81–8.

Picano E, Michelassi C. Chronic oral dipyridamole as a ‘novel’ antianginal drug: the collateral hypothesis. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;33(3):666–70.

De Schryver EL. Dipyridamole in stroke prevention: effect of dipyridamole on blood pressure. Stroke. 2003;34(10):2339–42.

De la Cruz JP, et al. Effect of aspirin plus dipyridamole on the retinal vascular pattern in experimental diabetes mellitus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280(1):454–9.

Leung GP, Man RY, Tse CM. D-Glucose upregulates adenosine transport in cultured human aortic smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288(6):H2756–62.

Pawelczyk T, Podgorska M, Sakowicz M. The effect of insulin on expression level of nucleoside transporters in diabetic rats. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63(1):81–8.

Buckley NE, et al. Immunomodulation by cannabinoids is absent in mice deficient for the cannabinoid CB(2) receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;396(2–3):141–9.

Crandall J, et al. Neuroprotective and intraocular pressure-lowering effects of (-)Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in a rat model of glaucoma. Ophthalmic Res. 2007;39(2):69–75.

Mechoulam R, Parker LA, Gallily R. Cannabidiol: an overview of some pharmacological aspects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42(11 Suppl):11S–9S.

Hampson AJ, et al. Cannabidiol and (-)Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol are neuroprotective antioxidants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(14):8268–73.

Malfait AM, et al. The nonpsychoactive cannabis constituent cannabidiol is an oral anti-arthritic therapeutic in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(17):9561–6.

El-Remessy AB, et al. Neuroprotective effects of cannabidiol in endotoxin-induced uveitis: critical role of p38 MAPK activation. Mol Vis. 2008;14:2190–203.

Braida D, et al. Post-ischemic treatment with cannabidiol prevents electroencephalographic flattening, hyperlocomotion and neuronal injury in gerbils. Neurosci Lett. 2003;346(1–2):61–4.

Mishima K, et al. Cannabidiol prevents cerebral infarction via a serotonergic 5-hydroxytryptamine1A receptor-dependent mechanism. Stroke. 2005;36(5):1077–82.

Rajesh M, et al. Cannabidiol attenuates high glucose-induced endothelial cell inflammatory response and barrier disruption. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293(1):H610–9.

Weiss L, et al. Cannabidiol lowers incidence of diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. Autoimmunity. 2006;39(2):143–51.

Barnes MP. Sativex: clinical efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of symptoms of multiple sclerosis and neuropathic pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2006;7(5):607–15.

Liou G, et al. Cannabidiol as a putative novel therapy for diabetic retinopathy: a postulated mechanism of action as an entry point for biomarker-guided clinical development. Curr Pharmacogenomics Person Med. 2009;7(3):215–22.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work has been supported by Vision Discovery Institute (GIL), Department of Defense (GIL), and Egyptian Cultural and Educational Bureau (ASI).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liou, G.I., Ahmad, S., Naime, M. et al. Role of adenosine in diabetic retinopathy. j ocul biol dis inform 4, 19–24 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12177-011-9067-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12177-011-9067-5