Abstract

Background

Recovery from myocardial infarction has been associated with patients’ perceptions of damage to their heart. New technologies offer a way to show patients animations that may foster more accurate perceptions and encourage medication adherence, increased exercise and faster return to activities.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of a brief animated intervention delivered at the patients’ bedside on perceptions and recovery in acute coronary syndrome patients.

Methods

Seventy acute coronary syndrome patients were randomly assigned to the intervention or standard care alone. Illness perceptions, medication beliefs and recovery outcomes were measured.

Results

Post-intervention, the intervention group had significantly increased treatment control perceptions and decreased medication harm beliefs and concerns. Seven weeks later, intervention participants had significantly increased treatment control and timeline beliefs, decreased symptoms, lower cardiac avoidance, greater exercise and faster return to normal activities compared to control patients.

Conclusions

A brief animated intervention may be clinically effective for acute coronary syndrome patients (Trial-ID: ACTRN12614000440628).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Steg PG, Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, et al. Baseline characteristics, management practices, and in-hospital outcomes of patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Am J Cardiol. 2002; 90: 358-363.

Cooper AF, Jackson G, Weinman J, Horne R. Factors associated with cardiac rehabilitation attendance: A systematic review of the literature. Clin Rehabil. 2002; 16: 541-552.

Worcester MUC, Murphy BM, Mee VK, Roberts SB, Goble AJ. Cardiac rehabilitation programmes: Predictors of non-attendance and drop-out. Eur J Cardiov Prev R. 2004; 11: 328-335.

Ewart CK, Taylor CB, Reese LB, DeBusk RF. Effects of early postmyocardial infarction exercise testing on self-perception and subsequent physical activity. Am J Cardiol. 1983; 51: 1076-1080.

Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F. Depression and anxiety as predictors of 2-year cardiac events in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2008; 65: 62-71.

Rudisch B, Nemeroff CB. Epidemiology of comorbid coronary artery disease and depression. Biol Psychiatr. 2003; 54: 227-240.

Lespérance F, Frasure-Smith N, Talajic M. Major depression before and after myocardial infarction: Its nature and consequences. Psychosom Med. 1996; 58: 99-110.

Thombs BD, Bass EB, Ford DE, et al. Prevalence of depression in survivors of acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med. 2006; 21: 30-38.

Riegel BJ. Contributors to cardiac invalidism after acute myocardial infarction. Coronary Artery Dis. 1993; 4: 215-220.

Thompson DR, Lewin RJP. Management of the post-myocardial infarction patient: Rehabilitation and cardiac neurosis. Heart. 2000; 84: 101-105.

Mittag O, Kolenda KD, Nordmann KJ, Bernien J, Maurischat C. Return to work after myocardial infarction/coronary artery bypass grafting: Patients’ and physicians’ initial viewpoints and outcome 12 months later. Soc Sci Med. 2001; 52: 1441-1450.

Petrie KJ, Weinman J, Sharpe N, Buckley J. Role of patients’ view of their illness in predicting return to work and functioning after myocardial infarction: longitudinal study. Brit Med J. 1996; 312: 1191-1194.

Soejima Y, Steptoe A, Nozoe S, Tei C. Psychosocial and clinical factors predicting resumption of work following acute myocardial infarction in Japanese men. Int J Cardiol. 1999; 72: 39-47.

Eagle KA, Kline-Rogers E, Goodman SG, et al. Adherence to evidence-based therapies after discharge for acute coronary syndromes: An ongoing prospective, observational study. Am J Med. 2004; 117: 73-81.

Horwitz RI, Viscoli CM, Donaldson RM, et al. Treatment adherence and risk of death after a myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1990; 336: 542-545.

Irvine J, Baker B, Smith J, et al. Poor adherence to placebo or amiodarone therapy predicts mortality: Results from the CAMIAT study. Psychosom Med. 1999; 61: 566-575.

Redfern J, Hyun K, Chew DP, et al. Prescription of secondary prevention medications, lifestyle advice, and referral to rehabilitation among acute coronary syndrome inpatients: Results from a large prospective audit in Australia and New Zealand. Heart. 2014; 100: 1281-1288.

Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The common sense representation of illness danger. In: Rachman S, ed. Contributions to medical psychology. New York: Pergamon Press; 1980: 7-30.

Cherrington CC, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Kennedy CW. Illness representation after acute myocardial infarction: Impact on in-hospital recovery. Am J Crit Care. 2004; 13: 136-145.

Juergens MC, Seekatz B, Moosdorf RG, Petrie KJ, Rief W. Illness beliefs before cardiac surgery predict disability, quality of life, and depression 3 months later. J Psychosom Res. 2010; 68: 553-560.

Dickens C, McGowan L, Percival C, et al. Negative illness perceptions are associated with new-onset depression following myocardial infarction. Gen Hosp Psychiatr. 2008; 30: 414-420.

Ades PA, Huang D, Weaver SO. Cardiac rehabilitation participation predicts lower rehospitalization costs. Am Heart J. 1992; 123: 916-921.

French DP, Cooper A, Weinman J. Illness perceptions predict attendance at cardiac rehabilitation following acute myocardial infarction: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2006; 61: 757-767.

Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999; 47: 555-567.

Broadbent E, Ellis CJ, Thomas J, Gamble G, Petrie KJ. Can an illness perception intervention reduce illness anxiety in spouses of myocardial infarction patients? A randomized controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2009; 67: 11-15.

Broadbent E, Ellis CJ, Thomas J, Gamble G, Petrie KJ. Further development of an illness perception intervention for myocardial infarction patients: A randomized controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2009; 67: 17-23.

Petrie KJ, Cameron LD, Ellis CJ, Buick D, Weinman J. Changing illness perceptions after myocardial infarction: An early intervention randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 2002; 64: 580-586.

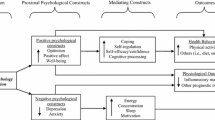

Williams B, Anderson AS, Barton K, McGhee J. Can theory be embedded in visual interventions to promote self-management? A proposed model and worked example. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012; 49: 1598-1609.

Devcich DA, Ellis CJ, Broadbent E, Gamble G, Petrie KJ. The psychological impact of test results following diagnostic coronary CT angiography. Health Psychol. 2012; 31: 738-744.

Devcich DA, Ellis CJ, Gamble G, Petrie KJ. Psychological responses to cardiac diagnosis: Changes in illness representations immediately following coronary angiography. J Psychosom Res. 2008; 65: 553-556.

Karamanidou C, Weinman J, Horne R. Improving haemodialysis patients’ understanding of phosphate-binding medication: A pilot study of a psycho-educational intervention designed to change patients’ perceptions of the problem and treatment. Brit J Health Psych. 2008; 13: 205-214.

Perera AI, Thomas MG, Moore JO, Faasse K, Petrie KJ. Effect of a smartphone application incorporating personalized health-related imagery on adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A randomized clinical trial. Aids Patient Care ST. 2014; 28: 579-586.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A, Buchner A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007; 39: 175-191.

Nash MP, Hunter PJ. Computational mechanics of the heart. J Elasticity. 2000; 61: 113-141.

Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006; 60: 631-637.

Broadbent E, Wilkes C, Koschwanez HE, Weinman J, Norton S, Petrie KJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the brief illness perception questionnaire. Psychol Health. 2015. doi:10.1080/08870446.2015.1070851.

Petrie KJ, Broadbent E, Kydd R. Illness perceptions in mental health: Issues and potential applications. J Ment Health. 2008; 17: 559-564.

Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Ellis CJ, Ying J, Gamble G. A picture of health—myocardial infarction patients’ drawings of their hearts and subsequent disability: A longitudinal study. J Psychosom Res. 2004; 57: 583-587.

Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: The development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health. 1999; 14: 1-24.

Eifert GH, Thompson RN, Zvolensky MJ, et al. The cardiac anxiety questionnaire: Development and preliminary validity. Behav Res Ther. 2000; 38: 1039-1053.

Horne R, Weinman J. Self-regulation and self-management in asthma: Exploring the role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medication. Psychol Health. 2002; 17: 17-32.

Rand CS, Wise RA. Measuring adherence to asthma medication regimens. Am J Resp Crit Care. 1994; 149: 69-76.

Kravitz RL, Hays RD, Sherbourne C, et al. Recall of recommendations and adherence to advice among patients with chronic medical conditions. Arch Intern Med. 1993; 153: 1869-1878.

Broadbent E, Ellis CJ, Gamble G, Petrie KJ. Changes in patient drawings of the heart identify slow recovery after myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 2006; 68: 910-913.

Vickers AJ, Altman DG. Statistics notes: Analysing controlled trials with baseline and follow up measurements. Brit Med J. 2001; 323: 1123-1124.

Perneger TV. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. Brit Med J. 1998; 316: 1236-1238.

Benner JS, Pollack MF, Smith TW, Bullano MF, Willey VJ, Williams SA. Association between short-term effectiveness of statins and long-term adherence to lipid-lowering therapy. Am J Health-Syst Ph. 2005; 62: 1468-1475.

Kaptein AA, Zandstra T, Scharloo M, et al. ‘A time bomb ticking in my head’: Drawings of inner ears by patients with vestibular schwannoma. Clin Otolaryngol. 2011; 36: 183-184.

Ramondt S, Tiemensma J, Cameron LD, Broadbent E, Kaptein AA. Patients’ drawings of blood cells reveal patients’ perception of sickle cell disease. Psychol Health. 2013; 28: 139-140.

Reynolds L, Broadbent E, Ellis CJ, Gamble G, Petrie KJ. Patients’ drawings illustrate psychological and functional status in heart failure. J Psychosom Res. 2007; 63: 525-532.

Tiemensma J, Daskalakis NP, van der Veen EM, et al. Drawings reflect a new dimension of the psychological impact of long-term remission of Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2012; 97: 3123-3131.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

ᅟ

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

Authors Jones, Ellis, Nash, Stanfield and Broadbent declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, A.S.K., Ellis, C.J., Nash, M. et al. Using Animation to Improve Recovery from Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Randomized Trial. ann. behav. med. 50, 108–118 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9736-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9736-x