Abstract

Background

Poor adherence hinders glaucoma treatment. Studies have identified demographic and clinical predictors of adherence but fewer psychological variables.

Purpose

We examined predictors from four health behavior theories and past research.

Methods

In the baseline phase of a three-site adherence study, before any intervention, 201 participants used electronic Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) bottles to monitor eyedrop use for 2 months, and completed questionnaires including self-reported adherence.

Results

MEMS showed 79 % adherence and self-report 94 % (0.5–1.5 missed weekly doses), but they correlated only r s = 0.31. Self-efficacy, motivation, dose frequency, and nonminority race/ethnicity predicted 35 % of variance in MEMS. Cues to action, self-efficacy, and intention predicted 20 % of variance in self-reported adherence.

Conclusions

Self-efficacy, motivation, intention, cues to action, dose frequency, and race/ethnicity each independently predicted adherence. Predictors from all theories were supported in bivariate analyses, but additional study is needed. Researchers and clinicians should consider psychological predictors of adherence. (ClinicalTrials.gov ID# NCT01409421.)

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Friedman DS, Wolfs RC, Colmain BJ, et al. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004; 122: 532-538.

Rossi GC, Pasinetti GM, Scudeller L, Radaelli R, Bianchi PE. Do adherence rates and glaucomatous visual field progression correlate? Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010; 21: 410-414.

Gordon ME, Kass MA. Validity of standard compliance measures in glaucoma compared with an electronic eyedrop monitor. In: Cramer JA, Spilker B, eds. Patient compliance in medical practice and clinicaltTrials. New York: Raven Press; 1991: 163-173.

Friedman DS, Quigley HA, Gelb L, et al. Using pharmacy claims data to study adherence to glaucoma medications: Methodology and findings of the glaucoma adherence and persistency study (GAPS). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48: 5052-5057.

Meichenbaum DC, Turk D. Facilitating treatment adherence: A practitioner's guidebook. New York: Plenum Press; 1987.

Okeke CO, Quigley HA, Jampel HD, et al. Adherence with topical glaucoma medication monitored electronically: The Travatan Dosing Aid Study. Ophthalmology. 2009; 116: 191-199.

Schmier JK, Covert DW, Robin AL. First-year treatment patterns among new initiators of topical prostaglandin analogs. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009; 25: 851-858.

Friedman DS, Hahn SF, Gelb L, et al. Doctor-patient communication, health-related beliefs, and adherence in glaucoma: Results from the glaucoma adherence and persistency study. Ophthalmology. 2008; 115: 1320-1327.

Friedman DS, Okeke CO, Jampel HD, et al. Risk factors for poor adherence to eyedrops in electronically monitored patients with glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2009; 116: 1097-1105.

Rees G, Leong O, Crowston JG, Lamoureux EL. Intentional and unintentional nonadherence to ocular hypotensive treatment in patients with glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2010; 117: 903-908.

Taylor SA, Galbraith SM, Mills RP. Causes of non-compliance with drug regimens in glaucoma patients: A qualitative study. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2002; 18: 401-409.

Lacey J, Cate H, Broadway DC. Barriers to adherence with glaucoma medications: A qualitative research study. Eye. 2009; 23: 924-932.

Tsai J, McClure CA, Ramos S, Schlundt DG. Compliance barriers in glaucoma: A systematic classification. J Glaucoma. 2003; 12: 393-398.

Khandekar R, Shama ME, Mohammed AJ. Noncompliance with medical treatment among glaucoma patients in Oman—a cross-sectional descriptive study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2005; 12: 303-309.

Djafari F, Lesk MR, Harasymowycz PJ, Desjardins D, Lachaine J. Determinants of adherence to glaucoma medical therapy in a long-term patient population. J Glaucoma. 2009; 18: 238-243.

Muir KW, Santiago-Turla C, Stinnett SS, et al. Health literacy and adherence to glaucoma therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006; 142: 223-226.

Cook PF. Adherence to medications. In: O'Donohue WT, Levensky ER, eds. Promoting treatment adherence: A practical handbook for health care providers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006: 183-202.

Mansberger SL. Are you compliant with addressing glaucoma adherence? Am J Ophthalmol. 2010; 149: 1.

Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Questions raised by a reasoned action approach: Comment on Ogden (2003). Health Psychol. 2004; 23: 431-434.

Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, Harman JJ. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006; 25: 462-473.

Cook PF, McElwain CJ, Bradley-Springer L. Feasibility of a PDA diary method to study daily experiences in persons living with HIV. Res Nurs Health. 2010; 33: 221-234.

Larsen KR, Voronovich ZA, Cook PF, Pedro L. Addicted to constructs: Science in reverse? Addictions. 2013; 108: 1532-1533.

Cane J, OConnor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012; 7: 37.

Chesney MA. The elusive gold standard: future perspectives for HIV adherence assessment and intervention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006; 43: S149-S155.

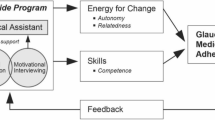

Cook PF, Bremer RW, Ayala AJ, Kahook MY. Feasibility of a motivational interviewing delivered by a glaucoma educator to improve medication adherence. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010; 4: 1091-1101.

Cook PF, Schmiege SJ, McClean M, Aagaard L, Kahook MY. Practical and analytic issues in the electronic assessment of adherence. West J Nurs Res. 2011; 34: 598-620.

Robin AL, Novak GD, Covert DW, Crockett RS, Marcic TS. Adherence in glaucoma: Objective measurements of once-daily and adjunctive medication use. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007; 144: 533-540.

Richardson C, Brunton L, Olleveant N, et al. A study to assess the feasibility of undertaking a randomized controlled trial of adherence with eye drops in glaucoma patients. Patient Prefer Adher. 2013; 7: 1025-1039.

Sleath B, Blalock S, Covert D, et al. The relationship between glaucoma medication adherence, eye drop technique, and visual field defect severity. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118: 2398-2402.

Liu H, Golin CE, Miller JG, et al. A comparison study of multiple measures of adherence to HIV protease inhibitors. Ann Intern Med. 2001; 134: 968-977.

Choo PF, Rand CS, Inui TS, et al. Validation of patient reports, automated pharmacy records, and pill counts with electronic monitoring of adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Med Care. 1999; 37: 846-857.

Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. AIDS Care. 2000; 12: 255-266.

Mathews WC, Mar-Tang M, Ballard C, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of early adherence after starting or changing antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2002; 16: 157-172.

Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. J Am Med Assoc. 2000; 283: 1715-1722.

Pakhomov SV, Jacobsen SJ, Chute CG, Roger VL. Agreement between patient-reported symptoms and their documentation in the medical record. Am J Manag Care. 2008; 14: 530-539.

Lewis SJ, Abell N. Development and evaluation of the Adherence Attitude Inventory. Res Soc Work Pract. 2002; 12: 107-123.

Barker GT, Cook PF, Kahook M, Kammer J, Mansberger SL. Psychometric properties of the Glaucoma Treatment Compliance Assessment Tool. May 5–9: Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Conference, Seattle WA, Session #346, Presentation #3522; 2013.

Cook PF. Patients' and health care practitioners' attributions about adherence problems as predictors of medication adherence. Res Nurs Health. 2008; 31: 261-273.

Collins LM, Schafer JL, Kam CM. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychol Methods. 2001; 6: 330-351.

Kazdin AE. Research design in clinical psychology. 2nd ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1992.

Mangione CM, Lee PP, Gutierrez PR, Spritzer K, Berry S, Hays RD. Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (VFQ-25). Arch Ophthalmol. 2001; 119: 1050-1058.

McHorney CA, Ware JE, Lu JFR, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994; 32: 40-66.

Kamarck TW. The Diary of Ambulatory Behavioral States: A new approach to the assessment of psychosocial influences on ambulatory cardiovascular activity. In: Krantz DS, Baum A, eds. Technology and methods in behavioral medicine. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998: 163-185.

Herzog TA, Blagg CO. Are most precontemplators contemplating smoking cessation? Assessing the validity of the stages of change. Health Psychol. 2007; 26: 222-231.

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

Dahlem NW, Zimet GD, Walker RR. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: A confirmation study. J Clin Psychol. 1991; 47: 756-761.

Stanley MA, Beck JG, Zebb BJ. Psychometric properties of the MSPSS in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 1998; 2: 186-193.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from Merck & Co., Inc., with additional research infrastructure support from the Colorado Clinical and Translational Science Institute, NIH grant #1UL1RR025780-01. The sponsor’s representative participated in design of the study and review of the manuscript, and Dr. Fitzgerald’s contributions are gratefully recognized with co-authorship credit. The authors wish to acknowledge Laurra Aagaard, Gordon Barker, Sandy Owings, Mary Preston, Scott Ruark, Christopher Shelvock, and Christina Sheppler for their contributions to this study.

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

Authors Paul F Cook, Sarah J. Schmiege, Steven Mansberger, Jeffrey Kammer, Timothy Fitzgerald, and Malik Y. Kahook declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. This study was reviewed for human subjects and confidentiality (HIPAA) compliance and approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Cook, P.F., Schmiege, S.J., Mansberger, S.L. et al. Predictors of Adherence to Glaucoma Treatment in a Multisite Study. ann. behav. med. 49, 29–39 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9641-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9641-8