Abstract

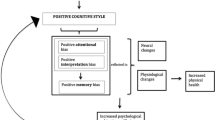

Despite the basic premise of behavioral medicine that understanding and treatment of physical well-being require a full appreciation of the confluence of micro-, molar-, and macro-variables, the field tends to focus on linear, causal relationships. In this paper, we argue that more attention be given to a dynamic matrix approach, which assumes that biological, psychological, and social elements are interconnected and continually influence each other (consistent with the biopsychosocial model). To illustrate, the authors draw from their independent and collaborative research programs on overlapping cardiac risk factors, symptom interpretation, and treatment delay for cardiac care and recovery from heart disease. “Cabling” across biological, psychological, and social variables is considered as a transformative strategy for medicine and the other health-related disciplines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Factors related bidirectionally influence each other. Variable A influences B and B influences A. An example from physics is: For a fixed volume, an increase in temperature will cause an increase in pressure; likewise, increased pressure will cause an increase in temperature.

References

Heron MP, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2009; 57 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2010 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2010; 121:e1–e170.

National Center for Health Statistics Health, United States, 2008 With Chartbook Hyattsville, MD: 2009

Engel, B. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977; 196: 129–136.

Schwartz G. Testing the biopsychosocial model: The ultimate challenge facing behavioral medicine. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982; 50: 1040–1050.

Suls J, Rothman, A. Evolution of the biopsychosocial model: Prospects and challenges for health psychology. Health Psychol. 2004; 23: 119–125.

American Heart Association, 2007 Heart and Stroke Statistics: 2007 Update. At a glance. Dallas, TX. Author.

Rozanski A, Blumenthal J, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. N Engl J Med. 1999; 99:2192–2217.

Friedman HS, Booth-Kewley S. The “Disease-Prone personality.” Am Psychol. 1987; 42: 539–555.

Frasure-Smith N Lesperance, F. Depression and other psychological risks following myocardial infarction. Arch Gen. Psychiatry. 2003; 60: 627–636.

Carney R Rich, M. Freedland K et al. Major depressive disorder predicts cardiac events in patients with coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 1988; 50: 627-633.

Davidson K, Kupfer D, Bigger J, et al. Assessment and treatment of depression in patients with cardiovascular disease: National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Working Group Report. Ann Behav Med. 2006; 32;121–126.

Rugulies R Depression as a predictor for coronary heart disease: A review and meta-analysis. Am J of Prevent Med. 2002; 23: 51–61.

Wulsin L, Singal B. Do depressive symptoms increase the risk for onset of coronary disease? A systematic quantitative review. Psychsom Med. 2003; 65: 6–17.

Writing Committee for the ENRICHD Investigators. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction. J Am Med Assoc. 2003; 289: 3106–3116.

Kawachi I, Sparrow D, Vokonas P, & Weiss, S. Symptoms of anxiety and risk of coronary heart disease: The Normative Aging Study. Circulation. 1994; 90: 2225–2229.

Matthews K. Coronary Heart Disease and Type A Behaviors: Update on and alternative to the Booth-Kewley and Friedman (1987) quantitative review. Psychol Bull. 1988; 3: 373–380.

Barefoot J, Dodge K, Peterson B, Dahlstrom W et al. The Cook-Medley Hostility Scale: Item content and ability to predict survival. Psychosom Med. 1989; 51: 46–57.

Smith TW Hostility and health: Current status of a psychosomatic hypothesis. Health Psychol. 1992: 11:139–150.

Krantz D, Manuck, S. Acute psychophysiological reactivity and risk of cardiovascular disease: A review and methodological critique. Psychol Bull. 1984; 96: 435–464.

Kop WJ. The integration of cardiovascular behavioral medicine and psychoneuroimmunology: New developments based on converging research fields. Brain, Behav Immunity. 2003; 17: 233–237.

Clark L A. The anxiety and depressive disorders: Descriptive psychopathology and differential diagnosis. In Kendall P, Watson D, eds Anxiety and Depression: Distinctive and Overlapping Features. San Diego: Academic; 1989: 83–129.

Mineka S, Watson D, Clark, L A. Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Ann Rev Psychol.1998; 49: 377–412.

Fawcett J, Kravitz, H. Anxiety syndromes and their relationships to depressive illness. J of Clin Psychiatry. 1983; 44: 8–11.

Suls J, Bunde J. Anger, anxiety and depression as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: The problems and implications of overlapping affective disposition. Psychol Bull. 2005; 131: 260–300.

Martin R & Watson D Style of anger expression and its relation to daily experience. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1997; 23: 285–294.

Watson DA, Clark LA (1984) Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience negative emotional states. Psychol Bull. 1984;96: 465–490.

Costa, P T, McCrae R. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI): Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. 1992.

Kop WJ. Chronic and acute psychological risk factors for clinical manifestations of coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 1999; 61: 476–487.

Smyth J., Stone, A. Ecological momentary assessment research in behavioral medicine. J Happiness Stud. 203; 4: 35–52, 2003.

Luger T, Lamkin D, Suls J. Relationship between depression and smoking: A meta-analysis. Unpublished manuscript, University of Iowa, 2010.

Bunde, J, Suls J. A quantitative synthesis of the relationship between the Cook-Medley Hostility Scale and traditional CHD risk factors. Health Psychol. 2006; 25: 493–500.

Engelberg H. Low serum cholesterol and suicide. Lancet. 1992;339:727–729.

Manfredini R, Caracciolom S, Salmi R, et al. The association of low serum cholesterol with depression and suicidal behaviors. J Int Med Res. 2000; 28: 245–257.

Grunfeld C, Feingold KR. Role of cytokines in inducing hyperlipidemia. Diabetes. 1992; 41 Suppl. 2: 97–101.

Shin J-Y, Suls J, Martin R. Are cholesterol and depression inversely related? A meta-analysis of the association between two cardiac risk factors. Ann Behav Med. 2008; 36; 33-43.

Angell, M. Disease as a reflection of the psyche. N Engl J Med. 1992:1570–1572. American Heart Association, 2007).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disparities in Adult Awareness of Heart Attack Warning Signs and Symptoms—14 States, 2005. MMWR. 2008; 57:175–179.

Turi Z, Stone P, Muller et al. Implications for acute intervention related to time of hospital arrival in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardio. 1986; 58: 203-209

Anand S, Xie C, Mehta S et al. Differences in the management and prognosis of women and men who suffer from acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll. Cardio. 2005; 46: 1845–1851.

Dracup K, Alonzo A, Atkins J et al. The physician’s role in minimizing pre-hospital delay in patients at risk of acute myocardial infarction: Recommendations for the National Heart Attack Alert Program. Ann Intern Med. 1997; 126:645–651.

Merz, CNB, Kelsey F, Pepine C, et al. The Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: Protocol design, feasibility. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999; 33: 1453–1461.

Mosca L, Mochari-Greenberger H, Dolor RJ et al. Twelve-year follow-up of American women's awareness of cardiovascular disease risk and barriers to heart health. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010; 3:118–119.

Shumaker S., Smith, T. Women and coronary heart disease: A psychological perspective. In Stanton A, Gallant S, eds. The Psychology of Women's Health. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1995; 25–49.

Wingard, D. L., Cohn, B. A., Cirillo, P. M., Cohen, R. D., & Kaplan, G. A. (1992). Gender differences in self-reported heart disease morbidity: Are intervention opportunities missed for women. J Women's Health. 1, 201–208.

Martin R, Gordon E, Lounsbury P. Gender disparities in the attribution of cardiac-related symptoms: Contributions of common-sense models of illness. Health Psychol. 1998;17:346–357.

Murdaugh C. Coronary artery disease in women. J of Cardiovascular Nurs. 1990;4: 35–50,

Hirsch, G, Meagher D. Women and coronary artery disease. Health Care for Women International. 1984; 5: 299–306.

Friedman M, Rosenman R. Type A Behavior and Your Heart. NY; Knopf: 1974.

Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The commonsense representation of illness danger. In Rachman S, ed. Medical psychology (vol. 2), NY: Pergamon Press; 1980: 17–30.

Martin R, Lemos K. From heart attacks to melanoma: Do common-sense models of somatization influence symptom interpretation for female victims? Health Psychol. 2002; 21; 25–32.

Martin R, Lemos K, Rothrock N. et al. Gender disparities in commonsense models of illness among myocardial infarction victims. Health Psychol. 2004; 23: 345–353.

Mechanic D. Social psychological factors affecting the presentation of bodily complaints. N Engl J Med. 1971; 286:1132–1139.

Pennebaker J. Psychology of Physical Symptoms. NY; Springer-Verlag: 1982

DeVon H, Ryan C, Ochs et al al. Symptoms across the continuum of acute coronary syndromes: Differences between women and men. Am J Crit Care. 2008; 17: 14–24.

Canto J, Goldberg R, Hand M et al. Symptom presentation of women with acute coronary syndromes. Arch Int Med. 2007; 167: 2405–2413.

Shin J-Y, Martin R, Suls J. Meta-analytic evaluation of gender differences and symptom management strategies in acute coronary syndromes. Heart & Lung. 2010; 39: 283–292.

Shin J-Y, Martin R, Howren M.B. Influence of assessment methods on reports of gender differences in AMI symptoms. West J Nurs Res. 2009; 31: 553–568.

Dusseldorp E, van Elderen T, Maes S, et al. A meta-analysis of psychoeducational programs for coronary heart disease patients. Health Psychol. 1999; 18: 506–519.

American College of Physicians. Position: Cardiac rehabilitation services. Ann Intern Med. 1998; 109: 650–663.

Hafstrom J, Schram V. Chronic illness in couples: Selected characteristics including wife’s satisfaction with and perception of marital relationships. Fam Relations. 1984; 33: 195–203.

Boogard M, Briody M. Comparison of the rehabilitation of men and women post-myocardial infarction. J Cardiopul Rehabil. 1985;5: 379–384.

Revenson T. Social support and marital coping with chronic illness. Ann Behav Med. 1994; 16: 122–130.

Rose G, Suls J, Green P et al. Comparisons of adjustment, activity, and tangible social support in men and women patients and their spouses during the 6-months post-myocardial infarction. Ann Behav Med. 1996; 18: 264–272.

Lemos K, Suls J, Jenson M et al. How do female and male cardiac patients and their spouses share responsibilities after discharge from the hospital? Ann Behav Med. 2003; 25: 8–15.

Hellerstein H, Franklin F (1984) Exercise testing and prescription. In Wenger N, Hellerstein H, eds. Rehabilitation of the Coronary Patient (2nd Ed.) NY: Wiley; 1984: 197–284.

Jenson M, Suls J, Lemos K. A comparison of physical activity in men and women with cardiac disease: Do gender roles complicate recovery? Women & Health. 2003; 37: 31–48.

Ainsworth B, Haskel W, Leon A, et al. Compendium of physical activities: Classsification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med & Science in Sports Exercise. 1993; 25: 71–80.

American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Guidelines for Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs (3rd ed). Champaign, IL; Human Kinetics: 1999.

Gilligan C. In A Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. 1982. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study is based on a Master Lecture delivered by J. Suls at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, Seattle, Washington. Research described here was supported by NIA AG024159 to JS, NIR 009292 to RM, and AHA 071001Z. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

About this article

Cite this article

Suls, J., Martin, R. Heart Disease Occurs in a Biological, Psychological, and Social Matrix: Cardiac Risk Factors, Symptom Presentation, and Recovery as Illustrative Examples. ann. behav. med. 41, 164–173 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9244-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9244-y