Abstract

Background

Obesity is associated with clinical depression among women. However, depressed women are often excluded from weight loss trials.

Purpose

This study examined treatment outcomes among women with comorbid obesity and depression.

Methods

Two hundred three (203) women were randomized to behavioral weight loss (n = 102) or behavioral weight loss combined with cognitive-behavioral depression management (n = 101).

Results

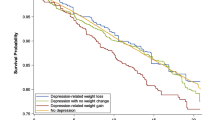

Average participant age was 52 years; mean baseline body mass index was 39 kg/m2. Mean Patient Health Questionnaire and Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL-20) scores indicated moderate to severe baseline depression. Weight loss and SCL-20 changes did not differ between groups at 6 or 12 months in intent-to-treat analyses (p = 0.26 and 0.55 for weight, p = 0.70 and 0.25 for depressive symptoms).

Conclusions

Depressed obese women lost weight and demonstrated improved mood in both treatment programs. Future weight loss trials are encouraged to enroll depressed women.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Carpenter KM, Hasin DS, Allison DB, Faith MS. Relationships between obesity and DSM-IV major depressive disorder, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts: Results from a general population survey. Am J Public Health 2000; 90: 251-7.

Simon GE, Von Korff M, Saunders K et al. Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch Gen Psychiat 2006; 63: 824-30.

Thande NK, Hurstak EE, Sciacca RE, Giardina EGV. Management of obesity: A challenge for medical training and practice. Obes 2008; 17: 107-13.

Goldstein LT, Goldsmith SJ, Anger K, Leon AC. Psychiatric symptoms in clients presenting for commercial weight reduction treatment. Int J Eat Disord 1996; 20: 191-7.

Clark MM, Niaura R, King TK, Pera V. Depression, smoking, activity level, and health status: Pretreatment predictors of attrition in obesity treatment. Addict Behav 1996; 21: 509-313.

Linde JA, Jeffery RW, Levy RL et al. Binge eating disorder, weight control self-efficacy, and depression in overweight men and women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004; 28: 418-25.

McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, Lang W, Hill JO. What predicts weight regain in a group of successful weight losers? J Consult Clin Psychol 1999; 67: 177-85.

Anderson RE, Wadden TA, Bartlett SJ, Zemel B, Verde TJ, Franckowiak SC. Effects of lifestyle activity vs. structured aerobic exercise in obese women: A randomized trial. JAMA 1999; 281: 335-40.

Wirth A, Krause J. Long-term weight loss with sibutramine: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 286: 1331-9.

Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behav Therapy 2004; 35: 205-30.

Cooper Z, Fairburn CG: A new cognitive behavioural approach to the treatment of obesity. Beh Res Therapy 2001; 39: 499-511.

Craigle MA, Nathan P. A nonrandomized effectiveness comparison of broad-spectrum group CBT to individual CBT for depressed outpatients in a community mental health setting. Behav Therapy 2009; 40: 302-14.

Wing RR. Behavioral approaches to the treatment of obesity, In Bray GA, Bouchard C, James WPT (eds), Handbook of Obesity. New York: Marcel Dekker, 1998; 855-78.

Wing RR, Jeffery RW. Benefits of recruiting participants with friends and increasing social support for weight loss and maintenance. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999; 67: 132-8.

Schneider KL, Bodenlos JS, Ma Y et al. Design and methods for a randomized clinical trial treating comorbid obesity and major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatr 2008; 8: 77.

Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Linde JA et al. Association between obesity and depression in middle-aged women. Gen Hosp Psychiat 2008; 30: 32-9.

Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. JAMA 1999; 282: 1737-44.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), Clinician Version. Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 1997.

Shear MK, Greeno C, Kang J et al. Diagnosis of nonpsychotic patients in community clinics. Am J Psychiatr 2000; 157: 581-7.

Derogatis L, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist: A measure of primary symptom dimensions. In: Pichot P, ed. Psychological Measurements in Psychopharmacology: Problems in Psychopharmacology. Basel, Switzerland: Kargerman; 1974: 79-110.

Mulrow CD, Williams JW Jr, Gerety MB, Ramirez G, Montiel OM, Kerber C. Case-finding instruments for depression in primary care settings. Ann Intern Med 1995; 122: 913-21.

Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatr 1996: 53: 924-32.

Simon GE, Von Korff M, Rutter C, Wagner E. A randomized trial of monitoring, feedback, and management of care by telephone to improve depression treatment in primary care. BMJ 2000; 320: 550-4.

Paffenbarger R, Wing A, Hyde R. Physical activity as an index of heart attack risk in college alumni. Am J Epidemiol 1978; 108: 161-75.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC et al. Compendium of Physical Activities: An update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sport Exer, 2000; 32 (Suppl): S498-S516.

Harris JK, French SA, Jeffery RW, McGovern PG, Wing RR. Dietary and physical activity correlates of long-term weight loss. Obes Res 1994; 2: 307-13.

Schakel SF. Procedures for estimating nutrient values for food composition databases. J Food Comp Anal 1997; 10: 102-14.

Schakel SF. Maintaining a nutrient database in a changing marketplace: Keeping pace with changing food products—A research perspective. J Food Comp Anal 2001; 14: 315-22.

Efron B. Forcing a sequential experiment to be balanced. Biometrika 1971; 58: 403-17.

Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics 1975; 31: 103-15.

Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Thorson C et al. Strengthening behavioral interventions for weight loss: A randomized trial of food provision and monetary incentives. J Consult Clin Psychol 1993; 61: 1038-45.

Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Thorson C, Burton LR. Use of personal trainers and financial incentives to increase exercise in a behavioral weight-loss program. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998; 66: 777-83.

Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Sherwood NE, Tate DF. Physical activity and weight loss: Does prescribing higher physical activity goals improve outcome? Am J Clin Nutr 2003; 78: 684-9.

Wing RR, Jeffery RW, Burton LR, Thorson C, Nissinoff KS, Baxter JE. Food provision vs. structured meal plans in the behavioral treatment of obesity. Int J Obes 1996; 20: 56-62.

Brown R, Lewinsohn P. A psychoeducational approach to the treatment of depression: Comparison of group, individual, and minimal contact procedures. J Consult Clin Psychol 1984; 52: 774-83.

Ludman EJ, Simon GE, Ichikawa L, et al. Does depression reduce the effectiveness of behavioral weight loss treatment? Behav Med 2009; 35: 126-134.

Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Arterburn D, Ichikawa L, Ludman EJ et al. Validity of clinical body weight measures as substitutes for missing data in a randomized trial. Obes Res Clin Pract 2008; 2: 277-81.

Paulose-Ram R, Safran MA, Jonas BS, Gu Q, Orwig D. Trends in psychotropic medication use among U.S. adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007; 16: 560-70.

Jeffery RW, Sherwood NE, Brelje K et al. Mail and phone interventions for weight loss in a managed-care setting: Weigh-to-be one-year outcomes. Int J Obes 2003; 27: 1584-92.

Andrews G. Placebo response in depression: Bane of research, boon to therapy. Br J Psychiatr 2001; 178: 192-94.

Butler AC, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for depression. Clin Psychol 1995; 48: 3-5.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant R01MH068127 (G. E. Simon, PI); ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00169273, “Epidemiology and Care of Comorbid Obesity and Depression.”

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Session topics: weight loss only and combined weight loss/depression group visits

Session | Weight loss only (90-min sessions) | Combined weight loss/depression (120-min sessions) |

|---|---|---|

1 | Orientation: group norms, introduction to self-monitoring, behavior change processes | Orientation: group norms, introduction to self-monitoring, behavior change processes, relation between depression and weight |

2 | Energy balance and healthy food choices | Energy balance and healthy food choices |

3 | Diet quality: Fat and cholesterol | Pleasant activities and depression I |

4 | High fiber, low fat eating | Pleasant activities and depression II |

5 | Increasing physical activity | Increasing physical activity |

6 | Lifestyle exercise | Lifestyle exercise, barriers to exercise |

7 | Barriers to exercise | Relaxation training |

8 | Eating patterns | Problem solving I |

9 | Eating in social situations | Problem solving II |

10 | Eating in restaurants | Eating patterns, eating in social situations, eating in restaurants |

11 | Re-evaluating diet and exercise goals I | Re-evaluating diet and exercise goals I |

12 | Re-evaluating diet and exercise goals II | Re-evaluating diet and exercise goals II |

13 | Stress and eating | Cognitive goals: monitoring thinking |

14 | Fad diets, weight loss medications, surgery for weight loss | Cognitive techniques: what’s the evidence? |

15 | Cues for eating and exercise | Cognitive techniques: thought balancing |

16 | Advanced diet change | Advanced diet change |

17 | Advanced exercise change | Advanced exercise change |

18 | Assertion and eating | Social skills and assertiveness I |

19 | High risk situations | Social skills and assertiveness II |

20 | Managing slips and lapses | Managing slips and lapses |

21 | Summing up | Summing up |

22 | Long-term self-care plan | Long-term self-care plan |

23 | Monthly check-in: review and reinforcement (diet and exercise; goals and motivation; plans for next month), ad hoc session content determined by group members | Monthly check-in: review and reinforcement (diet, exercise, pleasant activities, and thought balancing; goals and motivation; plans for next month), ad hoc session content determined by group members |

24–26 | Same as session 23 | Same as session 23 |

About this article

Cite this article

Linde, J.A., Simon, G.E., Ludman, E.J. et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Behavioral Weight Loss Treatment Versus Combined Weight Loss/Depression Treatment Among Women with Comorbid Obesity and Depression. ann. behav. med. 41, 119–130 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9232-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9232-2