Abstract

Background

Most research on adjustment of women undergoing genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility has not followed women for more than 6 months after result receipt and has not evaluated curvilinear patterns in general and cancer-specific adjustment.

Purpose

This study’s primary goal was to examine the trajectory of psychological status in women at risk for breast and ovarian cancer prior to undergoing genetic testing through 1 year after BRCA1/2 result receipt.

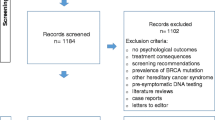

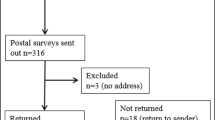

Methods

Women in the UCLA Familial Cancer Registry completed questionnaires assessing psychological status (i.e., depressive symptoms, negative and positive mood, anxiety, and cancer-related distress) prior to testing and at 1, 6, and 12 months after result receipt.

Results

Of 155 women tested, 117 were BRCA1/2− (96 uninformative negative and 21 true negative) and 38 were BRCA1/2+. Linear mixed model analyses revealed a consistent pattern in adjustment indicators, such that the groups did not differ at baseline, but mutation carriers endorsed significantly more depressive symptoms, negative mood, and cancer-specific distress relative to non-mutation carriers at 1 and 6 months after test result receipt (and less positive mood at 6 months only). At 12 months, negative and positive mood returned to baseline levels for mutation carriers, and depressive symptoms approached baseline. At 12 months, the groups differed significantly only on cancer-specific distress, owing to declining distress in non-carriers. Neither having a previous cancer diagnosis nor receiving a true negative versus uninformative negative result predicted reactions to genetic testing.

Conclusions

Genetic testing prompted an increase in general and cancer-specific distress for BRCA1/2+ women, which remitted by 1 year after result receipt.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994; 266: 66–71.

Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, et al. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature. 1995; 378: 789–792.

Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: A combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003; 72: 1117–1130.

Easton DF, Ford D, Bishop DT. Breast and ovarian cancer incidence in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 1995; 56: 265–271.

Ford D, Easton DF, Bishop DT, Narod SA, Goldgar DE. Risks of cancer in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Lancet. 1994; 343: 692–695.

Struewing JP, Hartge P, Wacholder S, et al. The risk of cancer associated with specific mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 among Ashkenazi Jews. N Engl J Med. 1997; 336: 1401–1408.

Szabo CI, King MC. Inherited breast and ovarian cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 1995; 4: 1811–1817.

Croyle RT, Smith KR, Botkin JR, Baty B, Nash J. Psychological responses to BRCA1 mutation testing: Preliminary findings. Health Psychol. 1997; 16: 63–72.

Arver B, Haegermark A, Platten U, Lindblom A, Brandberg Y. Evaluation of psychosocial effects of pre-symptomatic testing for breast/ovarian and colon cancer pre-disposing genes: A 12-month follow-up. Fam Cancer. 2004; 3: 109–116.

Claes E, Evers-Kiebooms G, Denayer L, et al. Predictive genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: Psychological distress and illness representations 1 year following disclosure. J Genet Couns. 2005; 14: 349–363.

Dorval M, Patenaude AF, Schneider KA, et al. Anticipated versus actual emotional reactions to disclosure of results of genetic tests for cancer susceptibility: Findings from p53 and BRCA1 testing programs. J Clin Oncol. 2000; 18: 2135–2142.

Kinney AY, Bloor LE, Mandal D, et al. The impact of receiving genetic test results on general and cancer-specific psychologic distress among members of an African-American kindred with a BRCA1 mutation. Cancer. 2005; 104: 2508–2516.

Lerman C, Narod S, Schulman K, et al. BRCA1 testing in families with hereditary breast-ovarian cancer. A prospective study of patient decision making and outcomes. JAMA. 1996; 275: 1885–1892.

Lodder L, Frets PG, Trijsburg RW, et al. Psychological impact of receiving a BRCA1/BRCA2 test result. Am J Med Genet. 2001; 98: 15–24.

Lodder L, Frets PG, Trijsburg RW, et al. One year follow-up of women opting for presymptomatic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2: Emotional impact of the test outcome and decisions on risk management (surveillance or prophylactic surgery). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002; 73: 97–112.

Reichelt JG, Heimdal K, Møller P, Dahl AA. BRCA1 testing with definitive results: A prospective study of psychological distress in a large clinic-based sample. Fam Cancer. 2004; 3: 21–28.

Schwartz M, Peshkin B, Hughes C, Main D, Isaacs C, Lerman C. Impact of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation testing on psychological distress in a clinic-based sample. J Clin Oncol. 2002; 20: 514–520.

Tercyak K, Lerman C, Peshkin B, et al. Effects of coping style and BRCA1 and BRCA2 test results on anxiety among women participating in genetic counseling and testing for breast and ovarian cancer risk. Health Psychol. 2001; 20: 217–222.

Cella D, Hughes C, Peterman A, et al. A brief assessment of concerns associated with genetic testing for cancer: The multidimensional impact of cancer risk assessment (MICRA) questionnaire. Health Psychol. 2002; 21: 564–572.

Halbert CH, Schwartz MD, Wenzel L, et al. Predictors of cognitive appraisals following genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. J Behav Med. 2004; 27: 373–392.

Watson M, Foster C, Eeles R, et al. Psychosocial impact of breast/ovarian (BRCA1/2) cancer-predictive genetic testing in a UK multi-centre cohort. Br J Cancer. 2004; 91: 1787–1794.

Meiser B, Butow P, Friedlander M, et al. Psychological impact of genetic testing in women from high-risk breast cancer families. Eur J Cancer. 2002; 38: 2025–2031.

Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001; 56: 218–226.

Becker MH, Maiman LA. Sociobehavioral determinants of compliance with health and medical care recommendations. Med Care. 1975; 13: 10–24.

Carver CS, Scheier MF. Principles of self-regulation: Action and emotion. In: Higgins ET, Sorrentino RM, eds. Handbook of Motivation and Cognition: Foundations of Social Behavior. New York: Guilford; 1990: 3–52.

Brickman P, Campbell DT. Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In: Appley MH, ed. Adaptation Level Theory: A Symposium. New York: Academic; 1971: 287–302.

Suh E, Diener E, Fujita F. Events and subjective well-being: Only recent events matter. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996; 70: 1091–1102.

van Roosmalen MS, Stalmeier PF, Verhoef LC, et al. Impact of BRCA1/2 testing and disclosure of a positive result on women affected and unaffected with breast or ovarian cancer. Am J Med Genet. 2004; 124A: 346–355.

Lerman C, Hughes C, Lemon SJ, et al. What you don’t know can hurt you: Adverse psychologic effects in members of BRCA1-linked and BRCA2-linked families who decline genetic testing. J Clin Oncol. 1998; 16: 1650–1654.

Diener E, Lucas RE, Scollon CN. Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. Am Psychol. 2006; 61: 305–314.

Coyne JC, Kruus L, Racioppo M, Calzone KA, Armstrong K. What do ratings of cancer-specific distress mean among women at high risk of breast and ovarian cancer? Am J Hum Genet. 2003; 116: 222–228.

Baum A, Friedman AL, Zakowski SG. Stress and genetic testing for disease risk. Health Psychol. 1997; 16: 8–19.

Dorval M, Gauthier G, Maunsell E, et al. No evidence of false reassurance among women with an inconclusive BRCA1/2 genetic test result. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005; 14: 2862–2867.

van Dijk S, Timmermans DR, Meijers-Heijboer H, Tibben A, van Asperen CJ, Otten W. Clinical characteristics affect the impact of an uninformative DNA test result: The course of worry and distress experienced by women who apply for genetic testing for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24: 3672–3677.

Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977; 1: 385–401.

Claus EB, Risch N, Thompson WD. Autosomal dominant inheritance of early-onset breast cancer. Implications for risk prediction. Cancer. 1994; 73: 643–651.

Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989; 81: 1879–1886.

Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988; 54: 1063–1070.

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State—Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1970.

Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The impact of event scale-revised. In: Wilson JP, Deane TM, eds. Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD. New York, NY: Guilford; 1997: 399–411.

Brain K, Norman P, Gray J, Mansel R. Anxiety and adherence to breast self-examination in women with a family history of breast cancer. Psychosom Med. 1999; 61: 181–187.

Diefenbach MA, Miller SM, Daly MB. Specific worry about breast cancer predicts mammography use in women at risk for breast and ovarian cancer. Health Psychol. 1999; 18: 532–536.

McCaul KD, Mullens AB. Affect, thought, and self-protective health behavior: The case of worry and cancer screening. In: Suls J, Wallston K, eds. Social Psychological Foundations of Health and Illness. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2003: 137–168.

Hay JL, McCaul KD, Magnan RE. Does worry about breast cancer predict screening behaviors? A meta-analysis of the prospective evidence. Prev Med. 2006; 42: 401–408.

O’Neill SC, DeMarco T, Peshkin BN, et al. Tolerance for uncertainty and perceived risk among women receiving uninformative BRCA1/2 test results. Am J Med Genet. 2006; 142C: 251–259.

Hay JL, Meischke HW, Bowen DJ, et al. Anticipating dissemination of cancer genomics in public health: A theoretical approach to psychosocial and behavioral challenges. Ann Behav Med. 2007; 34: 275–286.

McAllister M. Predictive genetic testing and beyond: A theory of engagement. J Health Psychol. 2002; 7: 491–508.

van Oostrom I, Meijers-Heijboer H, Lodder LN, et al. Long-term psychological impact of carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation and prophylactic surgery: A 5-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2003; 21: 3867–3874.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by funding from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation to Dr. Stanton. Dr. Ganz was supported through an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professorship and Dr. Vodermaier by a stipend from the Dr.-Werner-Jackstaedt-Stiftung of the Founder Association of the German Sciences (S134-10.021). The Cancer Center Core Grant (P30 CA 16042) and the Jonsson Cancer Center Foundation provided funding for the UCLA Familial Cancer Registry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Beran, T.M., Stanton, A.L., Kwan, L. et al. The Trajectory of Psychological Impact in BRCA1/2 Genetic Testing: Does Time Heal?. ann. behav. med. 36, 107–116 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9060-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9060-9