Abstract

Background

A causal chain linking exercise intensity, affective responses (e.g., pleasure–displeasure), and adherence has long been suspected as a contributor to the public health problem of physical inactivity. However, progress in the investigation of this model has been limited, mainly due to inconsistent findings on the first link between exercise intensity and affective responses.

Purpose

The purpose was to reexamine the intensity–affect relationship using a new methodological platform.

Methods

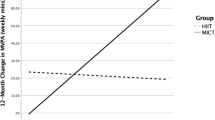

Thirty young adults (14 women and 16 men) participated in 15-min treadmill exercise sessions below, at, and above their ventilatory threshold. The innovative elements were the following: (a) Affect was assessed in terms of the dimensions of the circumplex model; (b) assessments were made repeatedly during and after exercise; (c) patterns of interindividual variability were examined; (d) intensity was determined in relation to the ventilatory threshold; and (e) hypotheses derived from the dual-mode model were tested.

Results

Intensity did not influence the positive changes from pre- to post-exercise, but it did influence the responses during exercise, with the intensity that exceeded the ventilatory threshold eliciting significant and relatively homogeneous decreases in pleasure.

Conclusions

Exceeding the intensity of the ventilatory threshold appears to reduce pleasure, an effect that could negatively impact adherence.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization. Annual global move for health initiative: A concept paper. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2003.

United States National Center for Health Statistics. Healthy people 2000 review, 1998–1999. Hyattsville, MD: Public Health Service; 1999.

Macera CA, Ham SA, Yore MM, et al. Prevalence of physical activity in the United States: Behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2001. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005; 2(2):A17.

Dishman RK. The problem of exercise adherence: fighting sloth in nations with market economies. Quest. 2001; 53: 279–294.

Dishman RK, Buckworth J. Adherence to physical activity. In: Morgan WP, ed. Physical Activity and Mental Health. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis; 1997: 63–80.

Perri MG, Anton SD, Durning PE, et al. Adherence to exercise prescriptions: effects of prescribing moderate versus higher levels of intensity and frequency. Health Psychol. 2002; 21: 452–458.

Cox KL, Burke V, Gorely TJ, Beilin LJ, Puddey IB. Controlled comparison of retention and adherence in home vs center initiated exercise interventions in women ages 40 65 years: the S.W.E.A.T. study (Sedentary Women Exercise Adherence Trial). Prev Med. 2003; 36: 17–29.

Lee JY, Jensen BE, Oberman A, et al. Adherence in the training levels comparison trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996; 28: 47–52.

Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Fortmann SP, et al. Predictors of adoption and maintenance of physical activity in a community sample. Prev Med. 1986; 15: 331–341.

National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Panel on Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health. Physical activity and cardiovascular health. J Am Med Assoc. 1996; 276: 241–246.

Morgan WP. Involvement in vigorous physical activity with special reference to adherence. Proceedings of the National College Physical Education Association for Men & National Association for Physical Education of College Women National Conference. Chicago, IL; 1977.

Pollock ML. How much exercise is enough. Phys Sportsmed. 1978; 6: 50–64.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010, vol 2. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000.

Ekkekakis P, Petruzzello SJ. Acute aerobic exercise and affect: current status, problems, and prospects regarding dose-response. Sports Med. 1999; 28: 337–374.

Emmons RA, Diener E. A goal-affect analysis of everyday situational choices. J Res Pers. 1986; 20: 309–326.

Kahneman D. Objective happiness. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N, eds. Well-being: The Foundation of Hedonic Psychology. New York: Sage; 1999: 3–25.

Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR. Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2000; 10: 295–307.

Berger BG, Owen DR. Mood alteration with yoga and swimming: aerobic exercise may not be necessary. Percept Mot Skills. 1992; 75: 1331–1343.

Carels RA, Berger B, Darby L. The association between mood states and physical activity in postmenopausal, obese, sedentary women. J Aging Phys Act. 2006; 14: 12–28.

Williams DM, Dunsiger S, Ciccolo JT, et al. Acute affective response to a moderate-intensity exercise stimulus predicts physical activity participation 6 and 12 months later. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2008; 9: 231–245.

Kiviniemi MT, Voss-Humke AM, Seifert AL. How do I feel about the behavior? The interplay of affective associations with behaviors and cognitive beliefs as influences on physical activity behavior. Health Psychol. 2007; 26: 152–158.

Ekkekakis P, Petruzzello SJ. Analysis of the affect measurement conundrum in exercise psychology: fundamental issues. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2000; 2: 71–88.

Ekkekakis P, Petruzzello SJ. Analysis of the affect measurement conundrum in exercise psychology: a conceptual case for the affect circumplex. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2002; 3: 35–63.

Russell JA. A circumplex model of affect. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980; 39: 1161–1178.

Acevedo EO, Rinehardt KF, Kraemer RR. Perceived exertion and affect at varying intensities of running. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1994; 65: 372–376.

Hall EE, Ekkekakis P, Petruzzello SJ. The affective beneficence of vigorous exercise revisited. Br J Health Psychol. 2002; 7: 47–66.

Hardy CJ, Rejeski WJ. Not what, but how one feels: the measurement of affect during exercise. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1989; 11: 304–317.

Parfitt G, Eston R. Changes in ratings of perceived exertion and psychological affect in the early stages of exercise. Percept Mot Skills. 1995; 80: 259–266.

Parfitt G, Eston R, Connolly D. Psychological affect at different ratings of perceived exertion in high-and low-active women: a study using a production protocol. Percept Mot Skills. 1996; 82: 1035–1042.

Parfitt G, Markland D, Holmes C. Responses to physical exertion in active and inactive males and females. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1994; 16: 178–186.

Morgan WP. Psychological benefits of physical activity. In: Nagle FJ, Montoye HJ, eds. Exercise in Health and Disease. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1982: 299–314.

Morgan WP. Methodological considerations. In: Morgan WP, ed. Physical Activity and Mental Health. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis; 1997: 3–32.

Van Landuyt LM, Ekkekakis P, Hall EE, Petruzzello SJ. Throwing the mountains into the lakes: on the perils of nomothetic conceptions of the exercise-affect relationship. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2000; 22: 208–234.

Wells JG, Balke B, Van Fossan DD. Lactic acid accumulation during work: a suggested standardization of work classification. J Appl Physiol. 1957; 10: 51–55.

Katch V, Weltman A, Sady S, Freedson P. Validity of the relative percent concept for equating training intensity. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1978; 39: 219–227.

Whipp BJ. Domains of aerobic function and their limiting parameters. In: Steinacker JM, Ward SA, eds. The Physiology and Pathophysiology of Exercise Tolerance. New York: Plenum; 1996: 83–89.

Cabanac M. Exertion and pleasure from an evolutionary perspective. In: Acevedo EO, Ekkekakis P, eds. Psychobiology of Physical Activity. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2006: 79–89.

Kirkcaldy BC, Shephard RJ. Therapeutic implications of exercise. Int J Sport Psychol. 1990; 21: 165–184.

Ojanen M. Can the true effects of exercise on psychological variables be separated from placebo effects. Int J Sport Psychol. 1994; 25: 63–80.

Ekkekakis P, Hall EE, Van Landuyt LM, Petruzzello SJ. Walking in (affective) circles: can short walks enhance affect. J Behav Med. 2000; 23: 245–275.

Saklofske DH, Blomme GC, Kelly IW. The effects of exercise and relaxation on energetic and tense arousal. Pers Individ Differ. 1992; 13: 623–625.

Thayer RE. Energy, tiredness, and tension effects of a sugar snack versus moderate exercise. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987; 52: 119–125.

Pronk NP, Crouse SF, Rohack JJ. Maximal exercise and acute mood response in women. Physiol Behav. 1995; 57: 1–4.

Ekkekakis P. Pleasure and displeasure from the body: perspectives from exercise. Cogn Emot. 2003; 17: 213–239.

Ekkekakis P. The study of affective responses to acute exercise: the dual-mode model. In: Stelter R, Roessler KK, eds. New Approaches to Sport and Exercise Psychology. Oxford, UK: Meyer & Meyer; 2005: 119–146.

Ekkekakis P, Hall EE, Petruzzello SJ. Variation and homogeneity in affective responses to physical activity of varying intensities: an alternative perspective on dose-response based on evolutionary considerations. J Sports Sci. 2005; 23: 477–500.

Ekkekakis P, Acevedo EO. Affective responses to acute exercise: toward a psychobiological dose-response model. In: Acevedo EO, Ekkekakis P, eds. Psychobiology of Physical Activity. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2006: 91–109.

Lang PJ. Behavioral treatment and bio-behavioral assessment: computer applications. In: Sodowski JB, Johnson JH, Williams TA, eds. Technology in Mental Health Care Delivery Systems. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1980: 119–137.

Russell JA, Weiss A, Mendelsohn GA. Affect Grid: a single item scale of pleasure and arousal. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989; 57: 493–502.

Svebak S, Murgatroyd S. Metamotivational dominance: a multimethod validation of reversal theory constructs. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985; 48: 107–116.

Thayer RE. The Biopsychology of Mood and Arousal. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989.

Thayer RE. Factor analytic and reliability studies on the Activation-Deactivation Adjective Check List. Psychol Rep. 1978; 42: 747–756.

Thayer RE. Activation-deactivation adjective check list: current overview and structural analysis. Psychol Rep. 1986; 58: 607–614.

Ekkekakis P, Hall EE, Petruzzello SJ. Evaluation of the circumplex structure of the Activation Deactivation Adjective Check List before and after a short walk. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2005; 6: 83–101.

Borg G. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1998.

Davis JA, Frank MH, Whipp BJ, Wasserman K. Anaerobic threshold alterations caused by endurance training in middle-aged men. J Appl Physiol. 1979; 46: 1039–1046.

Caiozzo VJ, Davis JA, Ellis JF, et al. A comparison of gas exchange indices used to detect the anaerobic threshold. J Appl Physiol. 1982; 53: 1184–1189.

Fox KR. The influence of physical activity on mental well-being. Public Health Nutr. 1999; 2: 411–418.

Ekkekakis P, Hall EE, Petruzzello SJ. Practical markers of the transition from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism during exercise: rationale and a case for affect-based exercise prescription. Prev Med. 2004; 38: 149–159.

Bixby WR, Spalding TW, Hatfield BD. Temporal dynamics and dimensional specificity of the affective response to exercise of varying intensity: differing pathways to a common outcome. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2001; 23: 171–190.

Acevedo EO, Kraemer RR, Haltom RW, Tryniecki JL. Perceptual responses proximal to the onset of blood lactate accumulation. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2003; 43: 267–273.

Parfitt G, Rose EA, Burgess WM. The psychological and physiological responses of sedentary individuals to prescribed and preferred intensity exercise. Br J Health Psychol. 2006; 11: 39–53.

Ekkekakis P, Hall EE, Peruzzello SJ. Some like it vigorous: measuring individual differences in the preference for and tolerance of exercise intensity. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2005; 27: 350–374.

Ekkekakis P, Lind E, Joens-Matre RR. Can self-reported preference for exercise intensity predict physiologically defined self-selected exercise intensity. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2006; 77: 81–90.

Ekkekakis P, Lind E, Hall EE, Petruzzello SJ. Can self-reported tolerance of exercise intensity play a role in exercise testing. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007; 39: 1193–1199.

Greene B. Get with the Program! Getting Real About Your Weight, Health, and Emotional Well-being. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2002.

Belman MJ, Gaesser GA. Exercise training below and above the lactate threshold in the elderly. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991; 23: 562–568.

Weltman A, Seip RL, Snead D, et al. Exercise training at and above the lactate threshold in previously untrained women. Int J Sports Med. 1992; 13: 257–263.

Ekkekakis P, Petruzzello SJ. Biofeedback in exercise psychology. In: Blumenstein B, Bar-Eli M, Tenenbaum G, eds. Brain and Body in Sport and Exercise: Biofeedback Application in Performance Enhancement. Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley; 2002: 77–100.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Ekkekakis, P., Hall, E.E. & Petruzzello, S.J. The Relationship Between Exercise Intensity and Affective Responses Demystified: To Crack the 40-Year-Old Nut, Replace the 40-Year-Old Nutcracker!. ann. behav. med. 35, 136–149 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9025-z

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9025-z