Abstract

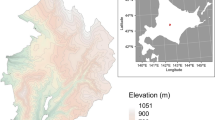

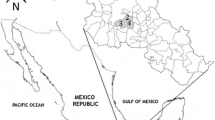

The aim of this study was to analyze the effects of intensive management and forest landscape structure (in terms of age class distribution) on timber and energy wood production (m3 ha−1), net present value (NPV, € ha−1) with implications on net CO2 emissions (kg CO2 MWh−1 per energy unit) from energy wood use of Norway spruce grown on medium to fertile sites. This study employed simulations using a forest ecosystem model and the Emission Calculation Tool, considering in its analyses: timber (saw logs, pulp) and energy wood (small-sized stem wood and/or logging residuals for top part of stem, branches, and needles) from the first thinning and harvesting residuals and stumps from the final felling. At the stand level, both fertilization and high pre-commercial stand density clearly increased timber production and the amount of energy wood. Short rotation length (40 and 60 years) outputted, on average, the highest annual stem wood production (most fertile and medium fertile sites), the 60 year rotation also outputted the highest average annual net present value (NPV with interest rates of 1–4%). On the other hand, even longer rotation lengths, up to 80 and 100 years, were needed to output the lowest net CO2 emissions per year in energy wood use. At the landscape level, the largest productivity (both for timber and energy wood) was obtained using rotation lengths of 60 and 80 years with an initial forest landscape structure dominated by older mature stands (a right-skewed age-class distribution). If the rotation length was 120 years, the initial forest landscape dominated by young stands (a left-skewed age-class distribution) provided the highest productivity. However, the NPV with interest rate of 2% was, on average, the highest with a right-skewed distribution regardless of the rotation length. If the rotation length was 120 years, normal age class distribution provided, on average, the highest NPV. On the other hand, the lowest emissions (kg CO2 MWh−1a−1) were obtained with the left-skewed age-class distribution using the rotation lengths of 60 and 80 years, and with the normal age-class distribution using the rotation length of 120 years. Altogether, the management regimes integrating both timber and energy wood production and using fertilization provided, on average, the lowest emissions over all management alternatives considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Briceño-Elizondo E, Garcia-Gonzalo J, Peltola H, Kellomäki S (2006) Carbon stocks in the boreal forest ecosystem in current and changing climatic conditions under different management regimes. Environ Sci Policy 9(3):237–252

Garcia-Gonzalo J, Peltola H, Zubizarreta A, Kellomäki S (2007) Impacts of forest landscape structure and management on timber production and carbon stocks in the boreal forest ecosystem under changing climate. For Ecol Manage 241:243–257

IPCC, The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2000) A special report of the IPCC. Land use, land-use change, and forestry. Cambridge University Press, p 30

Kellomäki S, Peltola H, Nuutinen T, Korhonen KT, Strandman H (2008) Sensitivity of managed boreal forests in Finland to climate change, with implications for adaptive management. Philos Trans R Soc 363:2341–2351

Lindner M (1999) Forest management strategies in the context of potential climate change. Forstwissenchafliches Centralblatt 118:1–13

Liski J, Pussinen A, Pingoud K, Mäkipää R, Karjalainen T (2001) Which rotation length is favourable to carbon sequestration? Can J For Res 31:2004–2013

Searchinger T, Heimlich R, Houghton RA, Dong FX, Elobeid A, Fabiosa J, Tokgoz S, Hayes D, Yu TH (2008) Use of US croplands for biofuels increases greenhouse gases through emissions from land-use change. Science 319:1238–1240

Melillo JM, Reilly JM, Kicklighter DW, Gurgel AC, Cronin TW, Paltsev S, Felzer BS, Wang XD, Sokolov AP, Schlosser CA (2009) Indirect emissions from biofuels: how important? Science 326:1397–1399

Aber JD, Botkin DB, Melillo JM (1978) Predicting the effects of different harvesting regimes on forest floor dynamics in northern hardwoods. Can J For Res 8:306–315

Cooper CF (1983) Carbon storage in managed forests. Can J For Res 13:155–166

Bradley D (2004) GHG Balances of forest sequestration and a bioenergy system, Case study for IEA Bioenergy Task 38 on GHG balance of biomass and bioenergy system; full report. Available at: http://www.ieabioenergy-task38.org/projects/task38casestudies/index1.htm. Accessed 15 Sept 2010

Cowie AL (2004) Greenhouse gas balance of bioenergy systems based on integrated plantation forestry in North East New South Wales, Australia, case study for IEA Bioenergy Task 38 on GHG balance of biomass and bioenergy system; full report. Available at: http://www.ieabioenergy-task38.org/ projects/task38casestudies/index1.htm

Jungmeier G, Schwaiger H (2000) Changing carbon storage pools in LCA of bioenergy—a static accounting approach for a dynamic effect. In: Life Cycle Assessment on forestry and forestry products. Cost Action E9, Brussels, Belgium, pp 101–105

Recommendations for Forest Management in Finland (2006) Hyvän metsänhoidon suositukset. Forestry Development Centre Tapio, Metsäkustannus Oy. 100 p. (In Finnish) English summary available at http://www.tapio.fi/finnish_forest_management_practice_recom

Kuusinen M, Ilvesniemi H (eds) (2008) Environmental effects of energywood harvesting, study report. Forestry Development Centre Tapio and Finnish Forest Research Institute, p 74 (In Finnish)

Skogsstyrelssen (2001) Rekommendationer vid uttag av skogsbränsle och kompensationsgödsling. Meddelande 2/2001 (in Swedish)

Aber J, Nadelhoffer K, Steudler P, Melillo J (1989) Nitrogen saturation in northern forest ecosystems. Bioscience 39:378–386

Aber J, McDowell W, Nadelhoffer K, Magill A, Berntson G, Kamakea M, McNulty S, Currie W, Rustad L, Fernandez I (1998) Nitrogen saturation in temperate forest ecosystems. Hypotheses revisited. BioScience 48:921–934

Tamm C (1991) Nitrogen in terrestrial ecosystems, questions of productivity, vegetational changes and ecosystem stability. Ecol Stud 81:115

Vitousek P, Howarth R (1991) Nitrogen limitation on land and in the sea—how can it occur? Biogeochem 13:87–115

Martikainen P, Aarnio T, Taavitsainen V-M, Päivinen L, Salonen K (1989) Mineralization of carbon and nitrogen in soil samples taken from three fertilized pine stands: long-term effects. Plant Soil 114:99–106

Södeström B, Bååth E, Lundgren B (1983) Decrease in soil microbial activity and biomass owing to nitrogen amendments. Can J Microbiol 29:1500–1506

Jarvis PG, Ibrom A, Linder S (2005) Carbon forestry-managing forests to conserve carbon. In: Griffiths H, Jarvis PG (eds) The carbon balance of forest biomes. Taylor & Francis Group, UK, pp 331–349

Hynynen J, Ahtikoski A, Siitonen J, Sievänen R, Liski J (2005) Applying the MOTTI simulator to analyse the effects of alternative management schedules on timber and non-timber production. For Ecol Manage 207:5–18

Kellomäki S, Väisänen H, Hänninen H, Kolström T, Lauhanen R, Mattila U, Pajari B (1992) Sima: A model for forest succession based on the carbon and nitrogen cycles with application to silvicultural management of the forest ecosystem. Silva Carelica 22:1–91

Hyytiäinen K, Ilomäki S, Mäkelä A, Kinnunen K (2006) Economic analysis of stand establishment for Scots pine. Can J For Res 36:1179–1189

Pretzch H, Grote R, Reineking B, Rötzer TH, Seifert ST (2008) Models for forest ecosystem management: a European perspective. Ann Bot 101:1065–1087

Consoli F, Allen D, Boustead I, Fava J, Franklin W, Jensen A, Oude N, Parrish R, Perriman R, Postlethwaite D, Quay B, Seguin J, Vigon B (1993) Guidelines for life-cycle assessment: a “code of practice”. Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry workshop report

UNEP (2003) Evaluation of environmental impacts in life cycle assessment. United Nations Environment Programme, Division of Technology, Industry and Economics, Production and Consumption Branch. Meeting Report. p 95

Kellomäki S, Strandman H, Nuutinen T, Peltola H, Korhonen KT, Väisänen H (2005) Adaptation of forest ecosystems, forests and forestry to climate change. (FINADAPT Working Paper 4) Finnish Environment Institute Mimeographs, p 334. Helsinki

Kolström M (1998) Ecological simulation model for studying diversity of stand structure in boreal forests. Ecol Modell 111:17–36

Kellomäki S, Kolström M (1993) Computations on the yield of timber by Scots pine when subjected to varying levels of thinning under changing climate in southern Finland. For Ecol Manage 59:237–255

Kolström M (1999) Effect of forest management on biodiversity in boreal forests: a model approach. Dissertation. University of Joensuu. Metsätieteellisen tiedekunnan tiedonantoja 86. Joensuu, p 29

Routa J, Kellomäki S, Peltola H, Asikainen A (2011) Impacts of thinning and fertilization on timber and energy wood production in Norway spruce and Scots pine: scenario analyses based on ecosystem model simulations. Forestry (in press)

Beuker E (1994) Long-term effects of temperature on the wood production of Pinus sylvestris L. and Picea abies (L.) Karst. Scand J For Res 9:34–45

Beuker E, Kolström M, Kellomäki S (1996) Changes in wood production of Picea abies and Pinus sylvestris under a warmer climate: comparison of field measurements and results of a mathematical model. Silva Fenn 30:239–246

Mäkipää R, Karjalainen T, Pussinen A, Kukkola M (1998) Effects of nitrogen fertilization on carbon accumulation in boreal forests: model computations compared with the results of long-term fertilization experiments. Chemosphere 36:1155–1160

Hynynen J, Ojansuu R, Hökkä H, Siipilehto J, Salminen H, Haapala P (2002) Models for predicting stand development in MELA System. Finnish Forest Research Institute, Research Papers 835, p 116

Finnish Statistical Yearbook of Forestry (2005) Finnish Forest Research Institute, p 418

Kilpeläinen A, Alam A, Strandman H, Kellomäki S (2010) Life cycle assessment (LCA) tool for estimating net CO2 exchange of forest production. Manuscript submitted to GCB Bioenergy

Cajander AK (1926) The theory of forest types. Acta For Fenn 29:1–108

Järvinen O, Vänni T (1994) Ministry of the Water and Environment Mimeograph 579, 1–68

Saksa T, Kankaanhuhta V (2007) Forest regeneration quality and the most important development issues in Southern Finland. Forest regeneration quality control–project final report, p 90 (In Finnish)

Äijälä O, Kuusinen M, Koistinen A (2010) Recommendations for energywood harvesting and management in Finland. Forestry Development Centre Tapio, Metsäkustannus Oy, p 31 (in Finnish)

Metinfo–Forest Information Services, Finnish Forest Research Institute (2009). Available at: http://www.metla.fi/metinfo/tilasto/index.htm (In Finnish). Accessed 20 Aug 2010

Ylimartimo M, Heikkilä J (2003) Automatization of seedling stands management. Forestry magazine. Metsätiet Aikak 4:429–437 (In Finnish)

Statistics Finland (2005) Available: http://www.stat.fi/tup/khkinv/polttoaineluokitus.html (in Finnish)

Sathre R, Gustavsson L, Bergh J (2010) Primary energy and greenhouse gas implications of increasing biomass production through forest fertilization. Biomass Bioenergy 34:572–581

Eriksson E, Gillespie AR, Gustavsson L, Langvall O, Olsson M, Sathre R, Stendahl J (2007) Integrated carbon analysis of forest management practices and wood substitution. Can J For Res 37:671–681

Oren R, Ellsworth D, Johnsen K, Phillips N, Ewers B, Maier C, Schäfer K, McCarthy H, Hendrey G, McNulty S, Katul G (2001) Soil fertility limits carbon sequestration by forest ecosystems in a CO2-enriched atmosphere. Nature 411:469–472

Johnson DW (1992) Effects of forest management on soil carbon storage. Water Air Soil Pollut 64:83–120

Nikinmaa E (1992) Analyses of the growth of Scots pine: matching structure with function. Acta Forestalia Fennica 235:1–68

Berg S, Karjalainen T (2003) Comparison of greenhouse gas emissions from forest operations in Finland and Sweden. Forestry 76:3271–3284

Karjalainen T, Asikainen A (1996) Greenhouse gas emissions from the use of primary energy in forest operations and long-distance transportation of timber in Finland. Forestry 69:215–228

Hämäläinen J, Oijala T, Rajamäki J (1992) Cost calculation model for site preparation. Metsämaan muokkauksen kustannuslaskentamalli. Metsäteho, Helsinki, p 13 (in Finnish)

Väkevä J, Pennanen O, Örn J (2004) Fuel consumption of timber trucks. Puutavara-autojen polttoaineen kulutus. Metsätehon raportti 166. Helsinki, p 32 (in Finnish)

Kuitto P-J, Keskinen S, Lindroos J, Oijala T, Rajamäki J, Räsänen T, Terävä J (1994) Mechanized cutting and forest haulage. Tiedotus Metsäteho, Helsinki. Report 410. p 47 ISBN 951-673-139-2 (in Finnish with English summary)

Mäkinen T, Soimakallio S, Paappanen T, Pahkala K, Mikkola H (2006) Greenhouse gas balances and new business opportunities for biomass-based transportation fuels and agrobiomass in Finland. Liikenteen biopolttoaineiden ja peltoenergian kasvihuonekaasutaseet ja uudet liiketoimintakonseptit Espoo 2006. VTT Tiedotteita. Research Notes 2357. 134 s (In Finnish)

Laitila J, Ala-Fossi A, Vartiamäki T, Ranta T, Asikainen A (1996) Kantojen noston ja metsäkuljetuksen tuottavuus [Productivity of stump lifting and forest haulage]. Metlan työraportteja, 46, 26. Helsinki (in Finnish)

Acknowledgments

This work is partly funded through the Finland Distinguished Professor Programme (FiDiPro) (2009–2012) of the Academy of Finland (Project No. 127299-A5060-06). Furthermore, the Graduate School in Forest Sciences and the School of Forest Sciences, at the University of Eastern Finland, and the Finnish Forest Research Institute (Eastern Finland Regional Unit, Joensuu), are acknowledged for support for this study. Additionally, Dr. David Gritten is thanked for revising the language of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Routa, J., Kellomäki, S. & Peltola, H. Impacts of Intensive Management and Landscape Structure on Timber and Energy Wood Production and net CO2 Emissions from Energy Wood Use of Norway Spruce. Bioenerg. Res. 5, 106–123 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-011-9115-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-011-9115-9