Abstract

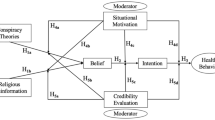

It has been established that vaccination is still one of the most effective ways to alleviate the sheer devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, various communication and psychological factors influence people’s willingness to get vaccinated. Anchored by the Extended Parallel Process Model (EPPM), this study analyzes a survey sample of 915 respondents from the United States and demonstrates that seeking COVID-19 news from social media was positively associated with perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, self-efficacy, and response efficacy. The increased self- and response efficacy were further positively tied to vaccination intention. Moreover, perceived susceptibility was positively associated with fear, while perceived severity was negatively related to fear, which in turn facilitated vaccination intention, constituting a serially mediating mechanism. Finally, people’s ability to identify misinformation was a significant moderator for the main association and the mediating effects. Specifically, vaccination intention became greater among those with a stronger ability to identify misinformation on social media infosphere. Theoretical and practical implications are further discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data can be made available upon reasonable request.

References

Ahmad, A. R., & Murad, H. R. (2020). The impact of social media on panic during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iraqi Kurdistan: Online questionnaire study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(5), e19556.

Allington, D., McAndrew, S., Moxham-Hall, V. L., & Duffy, B. (2021). Media usage predicts intention to be vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 in the US and the UK. Vaccine, 39(18), 2595–2603.

Amazeen, M. A. (2020). News in an era of content confusion: Effects of news use motivations and context on native advertising and digital news perceptions. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 97(1), 161–187.

Avery, E. J., & Park, S. (2018). HPV vaccination campaign fear visuals: An eye-tracking study exploring effects of visual attention and type on message informative value, recall, and behavioral intentions. Public Relations Review, 44(3), 321–330.

Barakat, K. A., Dabbous, A., & Tarhini, A. (2021). An empirical approach to understanding users’ fake news identification on social media. Online Information Review, 45(6), 1080–1096.

Bruns, A., Harrington, S., & Hurcombe, E. (2020). ‘Corona? 5G? or both?’: The dynamics of COVID-19/5G conspiracy theories on Facebook. Media International Australia, 177(1), 12–29.

Carcioppolo, N., Li, C., Chudnovskaya, E. V., Kharsa, R., Stephan, T., & Nickel, K. (2017). The comparative efficacy of a hybrid guilt-fear appeal and a traditional fear appeal to influence HPV vaccination intentions. Communication Research, 44(3), 437–458.

Chen, L., & Yang, X. (2019). Using EPPM to evaluate the effectiveness of fear appeal messages across different media outlets to increase the intention of breast self-examination among Chinese women. Health Communication, 34(11), 1369–1376.

Chung, M., & Jones-Jang, S. M. (2022). Red media, blue media, Trump briefings, and COVID-19: Examining how information sources predict risk preventive behaviors via threat and efficacy. Health Communication, 37(14), 1701–1714.

Craft, S., Ashley, S., & Maksl, A. (2017). News media literacy and conspiracy theory endorsement. Communication and the Public, 2(4), 388–401.

Emery, L. F., Romer, D., Sheerin, K. M., Jamieson, K. H., & Peters, E. (2014). Affective and cognitive mediators of the impact of cigarette warning labels. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 16(3), 263–269.

Fuchs, C. (2021). Bill Gates Conspiracy Theories as Ideology in the Context of the COVID-19 Crisis. In Communicating COVID-19. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Ghalavand, H., Panahi, S., & Sedghi, S. (2022). How social media facilitate health knowledge sharing among physicians. Behaviour & Information Technology, 41(7), 1544–1553.

Goodall, C. E., & Reed, P. (2013). Threat and efficacy uncertainty in news coverage about bed bugs as unique predictors of information seeking and avoidance: An extension of the EPPM. Health Communication, 28(1), 63–71.

Gore, T. D., & Bracken, C. C. (2005). Testing the theoretical design of a health risk message: Reexamining the major tenets of the extended parallel process model. Health Education & Behavior, 32(1), 27–41.

Hameleers, M., Powell, T. E., Van Der Meer, T. G., & Bos, L. (2020). A picture paints a thousand lies? The effects and mechanisms of multimodal disinformation and rebuttals disseminated via social media. Political Communication, 37(2), 281–301.

Hart, P. S., Chinn, S., & Soroka, S. (2020). Politicization and polarization in COVID-19 news coverage. Science Communication, 42(5), 679–697.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40.

Himelboim, I., Borah, P., Lee, D. K. L., Lee, J. (Janice), Su, Y., Vishnevskaya, A., & Xiao, X. (2023). What do 5G networks, Bill Gates, Agenda 21, and QAnon have in common? Sources, distribution, and characteristics. New Media & Society, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221142800

Honora, A., Wang, K. Y., & Chih, W. H. (2022). How does information overload about COVID-19 vaccines influence individuals’ vaccination intentions? The roles of cyberchondria, perceived risk, and vaccine skepticism. Computers in Human Behavior, 130, 107176.

Hwang, Y., Ryu, J. Y., & Jeong, S. H. (2021). Effects of Disinformation Using Deepfake: The Protective Effect of Media Literacy Education. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(3), 188–193.

Jones-Jang, S. M., Mortensen, T., & Liu, J. (2019). Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don’t. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 371–388.

Kim, K. S., Sin, S. C. J., & Tsai, T. I. (2014). Individual differences in social media use for information seeking. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(2), 171–178.

Knight, E., Intzandt, B., MacDougall, A., & Saunders, T. J. (2015). Information seeking in social media: A review of YouTube for sedentary behavior content. Interactive Journal of Medical Research, 4(1), e3835.

Krieger, J. L., & Sarge, M. A. (2013). A serial mediation model of message framing on intentions to receive the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: Revisiting the role of threat and efficacy perceptions. Health Communication, 28(1), 5–19.

Larson, H. J., & Broniatowski, D. A. (2021). Why debunking misinformation is not enough to change people’s minds about vaccines. American Journal of Public Health, 111(6), 1058–1060.

Lăzăroiu, G., & Adams, C. (2020). Viral panic and contagious fear in scary times: The proliferation of COVID-19 misinformation and fake news. Analysis and Metaphysics, 19, 80–86.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist, 46(8), 819.

Lin, H. C., & Chen, C. C. (2021). Disease prevention behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic and the role of self-esteem: An extended parallel process model. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 123.

Liu, S., Yang, J. Z., & Chu, H. (2021). When we increase fear, do we dampen hope? Using narrative persuasion to promote human papillomavirus vaccination in China. Journal of Health Psychology, 26(11), 1999–2009.

Lyons, B. A., Montgomery, J. M., Guess, A. M., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2021). Overconfidence in news judgments is associated with false news susceptibility. PNAS, 118(23), e2019527118.

Malecki, K. M., Keating, J. A., & Safdar, N. (2021). Crisis communication and public perception of COVID-19 risk in the era of social media. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 72(4), 697–702.

Maloney, E. K., Lapinski, M. K., & Witte, K. (2011). Fear appeals and persuasion: A review and update of the extended parallel process model. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(4), 206–219.

Mckinley, C. J., & Lauby, F. (2021). Anti-vaccine beliefs and COVID-19 information seeking on social media: Examining processes influencing COVID-19 beliefs and preventative actions. International Journal of Communication, 15, 4252–4274.

Neely, S., Eldredge, C., & Sanders, R. (2021). Health information seeking behaviors on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic among American social networking site users: Survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(6), e29802.

Nyhan, B. (2021). Why the backfire effect does not explain the durability of political misperceptions. PNAS, 118(15), e1912440117.

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior, 32(2), 303–330.

Pluviano, S., Watt, C., & Della Sala, S. (2017). Misinformation lingers in memory: Failure of three pro-vaccination strategies. PLoS ONE, 12(7), e0181640.

Popova, L. (2012). The extended parallel process model: Illuminating the gaps in research. Health Education & Behavior, 39(4), 455–473.

Roberto, A. J., Mongeau, P. A., Liu, Y., & Hashi, E. C. (2019). “Fear the flu, not the flu shot”: A test of the extended parallel process model. Journal of Health Communication, 24(11), 829–836.

So, J. (2013). A further extension of the Extended Parallel Process Model (E-EPPM): Implications of cognitive appraisal theory of emotion and dispositional coping style. Health Communication, 28(1), 72–83.

So, J., Kuang, K., & Cho, H. (2016). Reexamining fear appeal models from cognitive appraisal theory and functional emotion theory perspectives. Communication Monographs, 83(1), 120–144.

Su, Y. (2021). It doesn’t take a village to fall for misinformation: Social media use, discussion heterogeneity preference, worry of the virus, faith in scientists, and COVID-19-related misinformation beliefs. Telematics and Informatics, 58, 101547.

Tang, Y., Luo, C., & Su, Y. (2024). Understanding health misinformation sharing among the middle-aged or above in China: Roles of social media health information seeking, misperceptions and information processing predispositions. Online Information Review, 48(2), 314–333.

Thackeray, R., Crookston, B. T., & West, J. H. (2013). Correlates of health-related socialmedia use among adults. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(1), e21.

Thaker, J. (2021). The persistence of vaccine hesitancy: COVID-19 vaccination intention in New Zealand. Journal of Health Communication, 26(2), 104–111.

Thorson, E. (2016). Belief echoes: The Persistent effects of corrected misinformation. Political Communication, 33, 460–480.

Troiano, G., & Nardi, A. (2021). Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public Health, 194, 245–251.

Vraga, E. K., & Bode, L. (2017). Using expert sources to correct health misinformation in social media. Science Communication, 39(5), 621–645.

Vraga, E. K., & Bode, L. (2020). Defining misinformation and understanding its bounded nature: Using expertise and evidence for describing misinformation. Political Communication, 37(1), 136–144.

Vraga, E. K., & Tully, M. (2021). News literacy, social media behaviors, and skepticism toward information on social media. Information, Communication & Society, 24(2), 150–166.

Vraga, E. K., Tully, M., & Bode, L. (2020). Empowering users to respond to misinformation about Covid-19. Media and Communication (lisboa), 8(2), 475–479.

Wheaton, M. G., Prikhidko, A., & Messner, G. R. (2021). Is fear of COVID-19 contagious? The effects of emotion contagion and social media use on anxiety in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 567379.

Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs, 59(4), 329–349.

Witte, K. (1994). Fear control and danger control: A test of the extended parallel process model (EPPM). Communication Monographs, 61(2), 113–134.

Witte, K. (1998). Fear as motivator, fear as inhibitor: Using the extended parallel process model to explain fear appeal successes and failures. In P. Anderson (Ed.), Handbook of communication and emotion (pp. 423–450). Academic Press.

World Health Organization (2021, July 14). Vaccine efficacy, effectiveness, and protection. Retrieved February 17, 2023 from https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/vaccine-efficacy-effectiveness-and-protection

Xiao, X., Borah, P., & Su, Y. (2021). The dangers of blind trust: Examining the interplay among social media news use, misinformation identification, and news trust on conspiracy beliefs. Public Understanding of Science, 30, 977–992.

Xiao, X., Borah, P., Lee, D. K. L., Su, Y., & Kim, S. (2023). A story is better told with collective interests: An experimental examination of misinformation correction during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Health Promotion, 37(7), 915–923.

Yarchi, M., Samuel-Azran, T., & Hayat, T. Z. (2023). Perceived versus actual ability to identify fake news: Evidence from Israel’s 2019–2020 elections. International Journal of Communication, 17, 4974–4996.

Zhang, L., Kong, Y., & Chang, H. (2015). Media use and health behavior in H1N1 flu crisis: The mediating role of perceived knowledge and fear. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 23(2), 67–80.

Zhao, S., & Wu, X. (2021). From information exposure to protective behaviors: Investigating the underlying mechanism in COVID-19 outbreak using social amplification theory and extended parallel process model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 631116.

Funding

The research was not supported by any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The materials and procedures of the study was reviewed, and exemption determination of IRB review was attained from the Ethics Committee of the Human Research Protection Program at the university with which the second author was affiliated while designing and performing this study (IRB # 18846).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Participants signed informed consent regarding publishing their data.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, C., Su, Y. & Xiao, X. Social media news seeking and vaccination intention amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated serial mediation model. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06031-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06031-3